|

Abstract

Table of Contents

Introduction

Chapter 1

Part I

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Part II

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

|

Part I: Embodiment — and The

Incarnation

Chapter 9

The Ghost in the Machine

Evolution is

essentially a philosophy of materialism. No self-respecting evolutionist

will countenance the view that evolution provides only a partial

answer to the existence of a living world. Matter, life, consciousness,

and self-consciousness in an ascending scale form part of a great

chain in which there are no discontinuities, nothing that cannot

be quantified and ultimately understood in electrochemical terms.

The chain is deterministically

linked and must be preserved without the introduction of any

mechanism or any source of energy that is not absolutely part

of the system. The Universe is a uni-verse, not a multi-verse,

and one set of laws governs all that happens within it. Divine

interventions are unallowable.

Thus if there is such a thing as

soul or spirit or will or self-conscious mind, it is not another

order of reality but a direct outcome or spin-off of matter that

has reached a certain stage of complexity. Ernst Haeckel (1834—

1919) in an address before the German Association (of Science),

assured his audience that once the chemical constituents of a

cell

pg.1

of 16 pg.1

of 16

(carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen,

and sulphur) are correctly assembled, they "produce the

soul and the body of the animated world, and suitably nursed,

become man. . . . With this single argument the mystery

of the universe is explained, the Deity is annulled and a new

era of infinite knowledge is ushered in"! (79)

Today, those evolutionists who

are strictly logical in their thinking ought not to find anything

to quarrel with in this statement. Although they admit that there

are still many unanswered questions, they continue to have confidence

in the thesis. For many generations evolutionary biologists and

physiologists have interpreted their research findings in strict

compliance with this philosophy. Thus, when in recent years a

series of discoveries

have been made that challenge the view that man is effectively

a machine by "rumours of a ghost inside," all were

surprised — including the finders themselves.

One of the most

impressive lines of evidence of this "ghost" has come

from the work of Wilder Penfield who died recently after many

years of highly successful treatment of epileptic patients at

the Montreal Neurological Institute. During these years, Penfield

brought relief to well over a thousand subjects by a brain operation

which was daring indeed both in its conception and its execution.

What he found was as much a surprise to himself as it was to

his colleagues.

Now, to keep the record clear,

it is appropriate to note the very important distinction that

is being assumed between mind and brain throughout the rest of

this chapter. The mind is the thinking, the will, the conscious

attention, something non-physical, the self which scrutinizes

the situation or contemplates its meaning; the brain by contrast

is the organ which the mind uses, a physical object located in

the skull and composed of billions of nerve cells each of which

may have ten thousand connecting fibres to neighbour cells —

an incredibly complex structure.

79. Haeckel, Ernst, reported in Fortnightly

Review, London, vol.39, 1886, p.35.

pg.2

of 16 pg.2

of 16

Penfield

began his life work in the belief that the brain accounts for

the mind as the brook accounts for the babbling noise it makes.

Stop the flow of water and the babbling ceases; destroy the brain

and the mind is destroyed. Mind and babbling are epiphenomena

— not realities with independent existence.

Before describing this work, let

me quote something he wrote in retrospect after his retirement:

"Throughout my own scientific career, I, like other scientists,

struggled to prove that brain accounts for the mind. . . . Now,

perhaps, the time has come when we may profitably consider the

evidence as it stands, and ask the question: Do brain-mechanisms

account for the mind? Can the mind be explained by what is now

known about the brain? If not, which is the more reasonable of

the two hypotheses: that man's being is based on one element,

or on two?" (80)

Very briefly, the technique which

Penfield used was to lay bare a segment of the cortical surface

of the brain by removal of a portion of the skull. The motor

area thus exposed is known to be related to the involuntary movements

of epileptic subjects. The patient was lightly anaesthetized

locally for the opening up of the skull and felt little or no

pain, but was kept fully conscious because his or her ability

to communicate with the surgeon was essential to the success

of the operation.

The surgeon was thus enabled to

probe the surface of the brain in search of the damaged area.

The probe itself was composed of a single electrode, using a

60 cycle 2 volt current. Contact with the brain surface caused

no sensation of pain whatever, but when the damaged area is thus

stimulated, the patient at once becomes aware that an epileptic

fit is pending. By this means the offending tissue could be located

and, hopefully, corrective surgery applied.

Rapport between patient and surgeon

had to be at all times extremely close, and Penfield himself

inspired enormous confidence. But what he discovered unexpectedly

was that the electrode stimulation of very specific areas

80. Penfield, Wilder, Mystery of the Mind,

Princeton, Princeton University Press, 1975, p.xiii.

pg.3

of 16 pg.3

of 16

brought an experience

of recall for the patient which was so vivid that the subject

frequently suspected Penfield of using tape recordings. The recall

involved sound, coloured vision, and even odours. Any one area

could be contacted again and again and the recalled events would

be perfectly replayed in great detail in the patient's consciousness.

On one occasion the electrode was applied to the same spot 60

times and the recall experience was on each occasion precisely

the same. (81)

What was so surprising was that

the recall in no way at all interfered with the patient's full

awareness of all that was taking place in the operating room,

including conversations among the staff and even street noises

outside. The subject was experiencing two kinds of consciousness:

one from some long past situation, and the other from the circumstances

surrounding the operation. It was therefore quite possible for

the subject to live in two worlds and to discuss in great detail

the recalled events with those who occupied the operating theater.

It was also quite

possible for the patient, wherever the recall involved music,

to both whistle or hum the piece being played: and often even

to identify it.

One day, Penfield had an

experience which opened his eyes in a new way to the existence

of a ghost in the machinery. Here is how he described the event.

(82)

When the neurosurgeon

applies an electrode to the motor area of the patient's cerebral

cortex causing the opposite

hand to move, and when he asks the patient why he moved

his hand, the response is: 'I didn't do it. You made

me it. . .' It may be said that the patient thinks of himself

as having an existen separate from his body.

Once

when I warned a patient of my intention to stimulate the motor

area of the cortex, and challenged him to keep

his hand from moving when the electrode was applied, he seized

it with the other hand and struggled to hold it still.

Thus

one hand, under the control of the right

81. Penfield, Wilder and Phanor Perot, "The

Brain's Record of Auditory and Visual Experience: A Final Summary

and Discussion," Brain, vol.86, (4), Dec.,1963, p.685.

82. Penfield, Wilder, in the "Control of the Mind",

a Symposium held at the University of California Medical Centre,

San Francisco, 1961, quoted by A. Koestler, Ghost In the Machine,

London, Hutchinson, 1967, p.203f.

pg.4

of 16 pg.4

of 16

hemisphere driven by an electrode,

and the other hand which he controlled through the left hemisphere,

were caused to struggle against each other. Behind the 'brain

action' of one hemisphere was the patient's mind. Behind

the action of the other hemisphere was the electrode.

Penfield was

driven to conclude, therefore, that the brain was not causing

the mind but was the servant of it and its instrument for willed

action. This chance finding was repeated many times and has since

been experimentally demonstrated beyond a shadow of doubt. The

brain controls the action but the electrode controls the brain.

In all willed action, precisely the opposite is true: the mind

controls the brain and uses it to effect its purposes upon the

material world. To the extent that the brain is a physical organ

whose development has resulted from a combination of genetic

endowment and the accidents of experience, it must be said, as

Viktor Frankl put it, that while the brain conditions

the mind, it does not give rise to it. (83)

A second striking

proof of precedence of will over matter, of mind over brain,

has now been provided by some elegant experiments by H. H. Kornhuber.

(84)

To describe his findings with scientific

precision would be to snow the reader, and lose him! But very

simply, here is what he discovered. Whenever an action of any

kind is willed, measurable electrical potentials are generated

in the motor area of the cortex that controls the action. These

potentials are observed prior to the action that is willed but

only after the "willing." Thus between the conscious

exercise of will and the activity that results there is a clearly

measurable delay of sometimes up to several seconds duration.

In this brief but significant interval,

there is a flurry of electrical impulses over a wide area that

gradually narrows down and concentrates the signal to bring about

the precise movement willed. The delay between willing and activity

is quite measurable, and the nature of the will and the

83. Frankl, Viktor, in a discussion of J.

R. Smythies' paper, "Some Aspects of Consciousness"

in Beyond Reductionism, edited by Arthur Koestler and

J. R. Smythies, London, Hutchinson, 1969, p.254.

84. Kornhuber, H. H., "Cerebral Cortex, Cerebellum and Basal

Ganglia: an Introduction to their Motor Functions" in Neurosciences:

Third Study Programme, edited by F. O. Schmitt & F. G.

Worden, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 1973, pp.167-80.

pg.5

of 16 pg.5

of 16

resulting activity correspond.

In commenting on this discovery,

the neurophysiologist Sir John Eccles remarks, "it is rather

like the sergeant saying 'Company. . .' before giving the specific

command which is to follow. It seems to warn that the will is

about to act on the mechanism."

Eccles concludes, "Thus we

can regard these experiments as providing a convincing demonstration

that voluntary movements can be freely initiated independently

of any determining influences within the neuronal machinery of

the brain itself." (85) In short there really is a ghost in the machine,

capable of giving orders to the machinery and able to use the

machinery for its own purposes.

The problem that still remains, of course,

is how the mind or will (or, in our context, the spirit)

actually makes contact with the brain. I can normally move my

hand at will, but I cannot move the hands of my clock on the

wall. Clearly there is no connecting link with the clock hand

over which to mediate the message. But if my will is a non-physical

spirit, where is the actual connection with my own brain that

makes it move my own hand? The process is just as elusive. It

has been suggested that if we could really resolve this problem,

we might have a better idea of how God acts upon the physical

world, of how faith could move mountains; even of how the Lord

instantly stilled the violent storm on the Sea of Galilee. *

Descartes

recognized this interaction of spirit and body, and also that

it works both ways. Today we speak of these two kinds of interaction

as psychosomatic and somatopsychic, i.e., spirit/body and body/spirit

interactions

85. Eccles, Sir John & Karl R. Popper,

The Self and Its Brain, Springer Verlag, International,

1977, p.294.

* Perhaps the Lord Himself can take over the autonomy of the

human mind to use that mind's brain to effect a desired end:

for example, in the writing of Scripture, or in giving skill

to the hands — as He did to Bezaleel for the embellishment

of the Tabernacle (Exodus 36:1). And perhaps there is more truth

than we realize in the saying that the devil finds work for idle

hands to do.

pg.6

of 16 pg.6

of 16

depending upon which

takes the initiative. But like Descartes who finally abandoned

the search for the "contact point," we too have come

little or no nearer to a solution.

However, Descartes did uncover

a phenomenon that we all recognize readily enough when it is

pointed out to us in the right way, a phenomenon which clearly

demonstrates (as Penfield and Kornhuber have shown) that there

is someone there in the machinery making it work for us.

What we have in mind is the ability

we all possess to see the objective world stereoscopically, that

is to say, in depth, in three dimensions and not just in two

as an ordinary photograph presents it. We can perceive distance

between objects and we can perceive the roundness of things,

so that they are neither all at the same distance from us nor

are they flat.

We are able to do this because

we have two eyes spaced on average 650 mm. apart. By using a

camera with two lenses similarly spaced so that two separate

photographs of a scene can be taken at the same instant from

these two different positions, and by mounting these two photographs

appropriately so that each eye sees only one picture, we suddenly

find ourselves back in the three-dimensional world.

I have, and use, just such

a camera and never cease to be thrilled by the stereoscopic effect.

One wonders why these cameras are not more widely used, except

that one needs a special viewer.

Now the interesting thing is that

when one first looks into the viewer, one is met by two different

pictures. They are very little different, though they are momentarily

irreconcilable. The difference between the two pictures is clearly

revealed if we superimpose the one over the other and project

them together on to a screen. The picture on the screen will

be fuzzy and blurred, rather like a photograph taken by a camera

that has been moved slightly at a critical moment. No amount

of focussing of the projector will resolve the blurred or fuzzy

picture.

pg.7

of 16 pg.7

of 16

I

have emphasized this because it is of crucial importance. The

fact is that the two pictures cannot be reconciled in any way

by mere overlapping projection onto a screen, nor even by

projecting the two pictures through the lenses of the two eyes

on to the two retinas. Descartes presumed that the signals

from the two retinas which are screening two irreconcilable pictures

reach a single place in the brain where they coincide and fuse

themselves into a single picture in three-dimensional form. He

was never able to trace the nerves, or he would have discovered

that these two signals do not fuse as a single picture in the

brain but remain as independent signals

in the visual cortex, one in the left hemisphere and one in the

right hemisphere.

How, then, do the two conflicting

scenes come to be viewed as one? The conclusion is that the MIND

and not the BRAIN fuses and synthesizes them. So far it has been

impossible to say how this is done.

The fact is that when anyone for

the first time looks through my viewer, he or she will find that

the two views are not reconciled at once. But then quite suddenly,

in a way which is very hard to define but is a very real experience,

they are reconciled and two contradictory pictures in the flat

are instantly experienced as one in the round. The 'shift' is

remarkable and is very sudden. The two scenes converge unexpectedly

and, voilá, the picture emerges in three dimensions!

It is an interesting experience and a wonderful demonstration

of "mind" at work.

Moreover, from the moment the viewer

has achieved one three dimensional resolution, thereafter one

can go through several hundred pictures, and there is no such

experience of delay and sudden resolution as occurred in the

first viewing. Indeed, one develops a kind of 'pre-set' facilitation

that allows reconciliation to proceed much more rapidly, even

long after having laid aside the viewer. Days and months can

intervene, but the skill to obtain immediate stereo vision is

not lost. It would appear that the mind has learned the trick

of it.

pg.8

of 16 pg.8

of 16

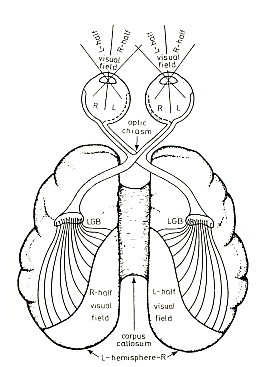

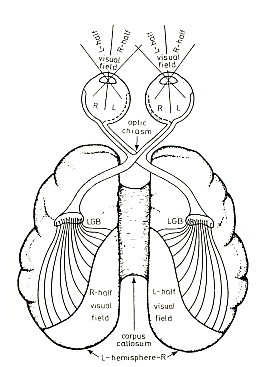

It

is not the two eyes which look out upon the distant scene that

give us a view of things in the round: it is the fusing

power, the reconciliation of two quite discrete and

Diagram showing how the pathways of the separate signals

from the two eyes lead to two separate areas of the brain.

pg.9

of 16 pg.9

of 16

subtly conflicting pictures

that is done by the mind. The brain provides the materials in

coded form: the mind or

soul or spirit uses these discrete materials to form a view of

reality that corresponds to reality in depth. Without this fusion,

all would be confusion. When the two signals are presented incorrectly

due to a fault in focussing power of either one of the eyes which

may have occurred as a result of a breakdown of the machinery,

it is the mind or soul or spirit which compensates by ignoring

one of the two inputs and thus resolves the irreconcilable conflict.

It is true that when this happens we lose depth perception but

at least the mind "makes sense" out of what the eyes

are signalling confusingly. The mind can only fuse what the brain

is presenting in the correct relationship.

Were it not for this power of the

mind to do what neither the camera nor the eyes themselves can

do, we would have to cover one eye to eliminate the contradictions

in the two pictures! But without stereovision we could

not perceive the depth or thickness of things, nor reach out

with perfect confidence and grasp them, nor even thread a needle

except with some difficulty and by constant trial and error.

To drive a car, we should have to gauge our distance from the

car ahead by its changing size, and the picture of the world

we have would be flat. We would get used to it. People with only

one eye do. But many kinds of "comprehension" of reality

in the physical world would be far more difficult, if not impossible.

It is doubtful if the soldering of an extremely small electronic

circuit manually could be done. In a thousand ways there

would be confusion until we had learned in each situation and

at that particular moment how to relate to space and distance.

By it, we know where we are within the framework of things.

The mind does for us what the eyes

cannot do, what the stereocamera cannot do, what the stereomicroscope

cannot do, what the stereoprojector cannot do — in short,

what no machine can do. It does this by fusing two flat

pictures that conflict, into one picture which provides the added

pg.10

of 16 pg.10

of 16

dimension of depth.

Without the mind to manage the input, there is no creation of

order, no meaningful fusion. The machine itself no more does

the fusing than the computer "adds." There is no adding

going on in the computer. It is just a machine re-routing signals

according to design in such a way as to give us a signal meaningful

only to the mind. The computer doesn't know what it is doing.

Now it is obvious that many animals

below man have stereoscopic vision, though not over quite as

wide a range in some cases. It must be assumed, therefore, that

in these animals, as in man, there is a ghost in the machinery

integrating the two discrete signals reaching the brain. Does

this then mean that animals also have a body/spirit constitution,

so that they too are souls?

The answer appears to be, Yes.

Indeed, the Hebrew word for soul (nephesh) is frequently

used of animals and was actually applied to animals (in Genesis

1:20, 21, 24 and 30) before it was applied to man! Is there no

difference, then, between man and the animals in this regard?

There certainly is, for although the fate of the bodies of both

men and animals is to return to the dust, the fate of the spirit

is quite different. Ecclesiastes 3:21 tells us that the spirit

of man goes upwards (i.e., returns to God who gave it, Ecclesiastes

12:7) but the spirit of the beast goes downwards to the earth

to share the fate of its body. In other words, the destiny of

the two is diametrically opposed.

We have been

using a number of terms such as mind, mindedness,

will, soul, spirit, etc.,

indiscriminately. It is unfortunate that there are so many terms

to describe the activities of the

ghost in the machine. All of these terms are appropriate and

each one of them is essentially a

spiritual faculty rather than a physical one. I want to say a

word about what is meant by

consciousness and the even more difficult-to-define phenomenon,

self-consciousness.

Children are occasionally born

without a brain. Yet they react to sounds and odours and to physical

contact

pg.11

of 16 pg.11

of 16

In spite of this reactivity,

there is no evidence of actual consciousness and, of course,

there is no brain to mediate it. Thus, in effect, there is "no

one there." They are alive but act like a person in a deep,

deep coma, except that they never will and never can come out

of it. They have no conscious contact with outside reality because

they have no cortex. This situation points up the fact that a

surprising level of reactivity is possible in the total absence

of consciousness.

If animals have consciousness,

then one must ask whether there are levels of consciousness corresponding

to the level of development of their central nervous system.

Plants, of course, "sense" the environment by various

means without a central nervous system and therefore presumably

cannot be said to have consciousness. Animals, on the other hand,

even the simplest of them like the amoebae, have consciousness

at least of other bodies around them: but man is intensely

self-conscious, i.e., conscious uniquely of his OWN body,

both in times of health

and in sickness.

The last point is important. Animals

seem obviously conscious of their own bodies in times of sickness

or when wounded, but man is conscious of his own body most of

his waking life. When a baby first discovers its hands and feet

are part of itself, the first glimmerings of self-consciousness

have probably been born. It is to be noted, therefore, that in

man the body introduces itself early in life and engenders a

new kind of consciousness, consciousness not merely of

other bodies but of one's own. We see our own bodies as something

possessed,

something we can stand apart from and consider objectively.

In this matter of personal body

identity, I think it is highly significant that man is the only

creature who cares for the bodies of his dead — including

his own! No animal is known to take anything more than a momentary

and passing interest in a dead body (except as food of course),

not even the dead body of its own mate. No attempt is made to

protect the body from predators once it is dead.

pg.12

of 16 pg.12

of 16

But even from the earliest times, as is known by the

presence of flowers in the grave, man has buried his dead quite

deliberately. Not infrequently the dead are placed in a foetal

position, a fact which some suggest is witness to a hope of re-birth

or reincarnation.

Theodosius Dobzhansky noted "that

all people everywhere take care of their dead in some fashion,

while no animal does anything of the sort." (86) And it is a significant

fact of human behaviour that a dead body continues to be protected

by custom or by law from injury. Indeed, we seem to have stricter

rules about the mutilation of the dead than we do of the living.

Man's consciousness of his own body or of the bodies of his fellow

men seems to be very different from mere animal consciousness.

Sir John C.

Eccles (Nobel Laureate for his work in neuro-physiology) in 1977

co-authored with Sir Karl R. Popper a fascinating book supporting

the reality of the soul or spirit and thus the dual nature of

the human constitution.

In the process of writing the book,

they had planned to title it The Self and The Brain. But

subsequently, they both became so convinced by the consideration

of the steadily accumulating experimental evidence of a managing

spirit or mind within the machinery, that they changed the title.

The change was a very small one from the typesetter's point of

view, but it was a highly significant one in its implications.

The new title became The Self and ITS Brain.

Eccles concludes that the self-conscious

mind is not simply engaged in passively observing the signals

from its body but in actively sorting them out. Continuously

displayed before it is a whole complex of neural inputs from

the eyes, the ears, the nose, and — be it noted — the

skin (which is the largest organ of the body). It selects from

this chain of signals in the brain whatever is of interest to

it, blending the result from different areas of the cortex. The

body supplies a rich input, and the mind deliberately disregards

some and attends to others.

86. Eccles, Sir John, Facing Reality,

New York,, Springer-Verlag, 1975, p.94, quoting Dobzhsnsky's

The Biology of Ultimate Concern.

pg.13

of 16 pg.13

of 16

In this way the self-conscious mind achieves a unity

of experience which becomes entirely personal. The brain

is its own brain, a personalized computer that it uses. According

to this hypothesis, the prime role in this process is played

by the self-conscious mind, exercising both its selective and

its integrative abilities.

They were impressed with the bond

which exists between spirit and body, a bond often commented

upon by theologians in the past from Thomas Aquinas (1224 —1274)

to James Orr (1844—1913), and right down to a number of present

writers. All have sensed the closeness of this bond which arises

out of or generates in man a strong sense of personal identity,

far more profound than is to be observed in any animal. It is

a form of consciousness that is related entirely to the spirit's

awareness of its own body, which is now acknowledged by some

of the best modern students of animal life as being unique to

man.

James Orr made much of this bond

and attributed to it the abhorrence of physical death which seems

to have characterized man's thinking throughout history. (87) The spirit in man, though

burdened by the body that spoils so many of his highest aspirations

because of its demands, nevertheless is so strongly attached

to it that it fears the rupture of death throughout life. The

most dramatic and most perceptive definition of death, and the

truest theologically considered, is still "the separation

of the spirit from the body." This is what death is.

We long to be freed because it

is a house in ruins, but we tremble at the prospect of this separation

as one might tremble at the loss of a companion of a lifetime,

and that is what the body has been.

Mind or spirit is the seat of authority.

The brain is an instrument which serves it. The whole is integrated,

unified, ordered by the mind. This non-physical reality is master

of the meaningful operation of the body which is, ideally, its

servant, but due to the Fall may and does become its master all

too often.

87. Orr, James, God's Image in Man,

Grand Rapids, Eerdmans, reprint 1948, p.252.

pg.14

of 16 pg.14

of 16

This

struggle is graphically described by Paul in chapter 7 of Romans.

The Fall had consequences as fatal to the body as to the spirit.

We see interaction for both good and ill exemplified throughout

Scripture.

The Lord remarked sadly upon it

in Matthew 26:41, "The spirit is willing but the flesh is

weak," as He came to his companions in his terrible hour

of anticipation and found them, alas, asleep. Paul bewailed it

when he cried out, "O wretched man that I am! Who shall

deliver me from this body of death" — while at the same

time saying that he really had no desire at all to be unclothed,

i.e., disembodied; though meanwhile he groaned in the body he

had (2 Corinthians. 5:4). Here was an unwanted interaction.

But the Bible speaks of co-operative

interaction as well. In a passage seldom noted (Mark 9:29), after

the disciples had come to the Lord in surprise that their newly

delegated power to heal sickness had failed them, Jesus said,

"This kind comes forth by nothing but by prayer and fasting."

By prayer which is a discipline of the spirit, and by fasting

which is a discipline of the body. There are some battles with

Satan that require the whole man, body and spirit — despite

the fact that the battle is a spiritual one.

Man has a brain

that is clearly a kind of computer. This is what man HAS, but

it is not what man IS. Man is truly a spiritual creature but

he is an incarnate, embodied creature, unique among all other

creatures because of the uniqueness of the origin and destiny

of both his body and his spirit.

It is remarkable that a man of

Eccles' stature and experience who nevertheless does not share

our Christian convictions, should arrive at this same conclusion,

and in doing so should reject the evolutionary origin of the

soul. He did so in spite of the fact that his co-author, Karl

Popper, accepted it without equivocation.

In another of his recent works,

Facing Reality, Eccles observes that statements about

"the progressive emergence of conscious mind during evolution

are not supported by

pg.15

of 16 pg.15

of 16

any scientific evidence,

but are merely statements made within the framework of a faith

that evolutionary

theory, as it now is, will at least in principle explain fully

the origin and development of all living forms including our

selves." (88)

This "faith" is

being steadily eroded by experimental evidence. There IS a ghost

in the machine.

88. Eccles, Sir John, Facing Reality,

New York, Springer-Verlag, 1975, p.91.

pg.16

of 16 pg.16

of 16  Copyright © 1988 Evelyn White. All rights

reserved

Previous Chapter Next

Chapter

Copyright © 1988 Evelyn White. All rights

reserved

Previous Chapter Next

Chapter

|