|

Abstract

Table of Contents

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Epilogue

Response

Further Reading

|

The Mysterious Matter of Mind

Chapter Five

Laying the Experimental Foundations

One of

Sherrington's most notable pupils was the Canadian neurosurgeon

Dr. Wilder Penfield. He is best known for his remarkable studies

of, and successful treatment of, hundreds of patients afflicted

with epilepsy. This work involved surgical exposure and electrode

stimulation of brain tissue in fully conscious patients. By observing

the patient's reaction as the electrode was moved gently from

point to point over the temporal lobe, it proved possible in

many cases to locate the area of damaged tissue causing the epilepsy.

Excising these damaged tissues

reduced and sometimes halted the recurrence of fits. An unexpected

discovery was the finding that in many cases there was involuntary

recall of extremely vivid and often dramatic scenes from the

patient's past life, which scenes he or she was able to describe

in great detail, being fully conscious of the surgeon's activity.

This work was carried out in the Montreal Neurological Institute

over a period of thirty years.

In his training at Oxford under

Sir Charles Sherrington

pg.1

of 12 pg.1

of 12

and for a short period

under Dr. Santiago Ramon-y-Cajal in Spain, Penfield absorbed

and wholly accepted the principle that all such experimental

work must be conducted with the assumption that mind is in

the brain, that mind will in due course be entirely explained

in terms of physics and chemistry and electrical circuitry.

At the close of active surgical

practice he observed: (49)

Throughout my own scientific

career, I, like the other scientists, have struggled to prove

that the brain accounts for the mind. But now, perhaps, the time

has come when we may profitably consider the evidence as it stands,

and ask the question: "Do brain mechanisms account for

the mind?" Can the mind be explained by what is now

known about the brain? If not, which is the more reasonable of

the two possible hypotheses: that man's being is based on one

element, or on two?

This shift in

point of view was not made easily. In 1950 Penfield outlined

briefly but eloquently an entirely mechanistic interpretation

of the brain's functioning. But subsequent evidence gradually

convinced him that this mechanistic and monistic view did not

adequately account for the facts. He wrote subsequently, "Something

else finds its dwelling place between the sensory complex and

the motor mechanism. . . . There is a switchboard operator

as well as a switchboard." (50)

In his Mystery of the Mind,

there is a frank discussion of the thoughts which went continually

through his mind as he probed the brain tissues of epileptic

patients in the search for root causes. He wrote that, while

agreeing with Lord Adrian that we must always guard against introducing

ideas into our science which are not part of science, yet we

must subject our research to our own speculation at times and

that, where we do, critical evaluation is still possible. (51)

He then describes very briefly

the procedure which he came to adopt in the operating room and

the rationale behind it. The object was to locate, in epileptic

subjects, the cause and location of the point of irritation of

the neuron bombardment which is the trigger of the epileptic

fit, and, having precisely located it, to excise the tissue in

that area. The procedure

49. Penfield, Wilder, The Mystery of the

Mind, Princeton University Press, 1975, p.xiii.

50. Penfield, Wilder, The Physical Basis of Mind, edited

by P. Laslett, Oxford, Basil Blackwell, 1950, p.64.

51. Penfield, Wilder, The Mystery of the Mind, Princeton

University Press, 1975, pp.4—5.

pg.2

of 12 pg.2

of 12

was found to be successful

in hundreds of cases without further ill effect, provided that

only one hemisphere had been damaged. The contralateral tissue

in the other hemisphere (when the triggering site lay in the

temporal lobe) was able to take over the function of the excised

tissue. (See Figure 2 for area identity.)

Figure 2. Showing the relation of the

temporal lobe to the rest of the brain.

Penfield said

further that, for safety's sake and a fair likelihood of cure,

the surface of one hemisphere of the brain needs to be bared

extensively in order to study and possibly excise a damaged part.

This operation was considered less dangerous and more helpful

if the patient was conscious and alert during the entire procedure,

so only a local painkiller was injected into the patient's scalp.

Penfield emphasized that a great amount of doctor-patient trust

and communication were necessary to make such an operation both

successful and humane. (52) This procedure sometimes revealed the site that caused

epileptic seizures by triggering one.

To the layman, it seems an awesome

undertaking. But the secret of success depends on the patient's

being able to tell the surgeon what his conscious experience

is as the operator explores the exposed cerebral tissue with

the electrode. [A single contact point is used, carrying a 60-cycle

2-volt current.] Without this, the only guide to the surgeon

would be spasmodic and involuntary muscular

52. Ibid., p.12.

pg.3

of 12 pg.3

of 12

movements. Since the

stimulation of the temporal lobe does not produce such movements,

only the conscious patient can tell the surgeon of the effects

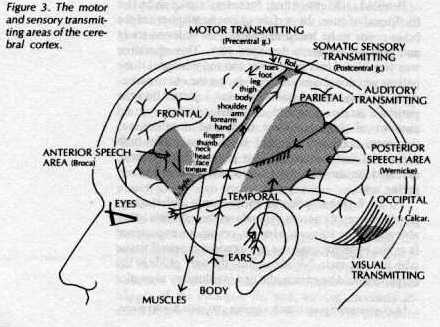

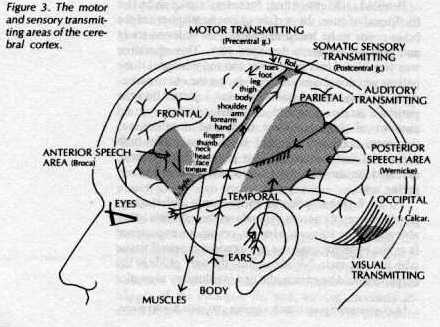

of exploration. (See Figure 3 for map of motor-control areas).

Double Consciousness

This has produced

the surprising and remarkable experience in the subject of a

form of double consciousness, as Penfield termed it. The

patient is not only fully aware of his immediate surroundings,

operating room, the surgeon and his assistants — whole local

scene in fact — but also of the suddenly re-enacted

scene from the past, a scene so vivid that it includes sounds,

and in one case even included the odour of coffee being brewed!

He records one such occasion in

which "a young South African patient lying on the operating

table exclaimed, when he realized what was happening, that it

was astonishing to him to realize that he was laughing

pg.4

of 12 pg.4

of 12

with his cousins on a

farm in South Africa, while he was also fully conscious of being

in the operating room in Montreal." Penfield observed: "The

mind of the patient was as independent of the reflex action as

was the mind of the surgeon who listened and strove to understand.

Thus, my argument favours independence of mind-action."

(53)

Penfield was thus driven to conclude

that the stimulus of the electrode was responsible in effect

for a kind of TV program which the subject was watching objectively,

while the subject's own mind was directing the production

of an equally complete record of the events occurring in the

room around him. Just as we can objectively watch a TV program

in the company of others whose presence we are fully conscious

of, so here were two different kinds of consciousness. The mind

was observing by its own will a program presented to it mechanistically

by electrode stimulation much as the TV operated independently

of the viewer. As Penfield put it, if we liken the brain to a

computer, man has a computer, not is a computer.

(54)

This discovery was totally unexpected.

But it was in no way singular. It was repeated again and again

for hundreds of patients, each of whom could identify the scene

recalled with ease and virtually instantaneously. Patients could

elaborate on what they saw and explain the circumstances, much

as a TV viewer seeing a serial program might explain the circumstances

to a watching companion who was ignorant of the previous events.

In such a situation there are clearly two elements. The viewer

is not part of the TV program but an observer. Yet he

is more than an observer insofar as the viewer can adjust the

set, clarify the image, change the program, and (in a recall

situation) shut it off at will under normal circumstances by

a shifting of attention (i.e., turning to another program). Here,

then, we have a dualism of object and subject, of brain and mind.

It is no longer safe to view the

mind as a computer, though the brain is indeed a computer

of extraordinary refinement. But this computer has a programmer

and an operator who is using it as a tool of recall and of motor

control. (55)

53. Ibid., p.55.

54. Ibid., p.108.

55. Ibid., p.40.

pg.5

of 12 pg.5

of 12

Supervisory Control

by the Mind

Epileptic

subjects may sometimes experience total "blackout"

as to consciousness, the mind apparently ceasing entirely to

control the brain. Provided that the brain has already been programmed,

the subject becomes an automaton and completes it in a state

of total mindlessness. Patients may even complete a journey from

work by car. Provided the journey is a habitual one and

that no unexpected interference occurs, navigating the traffic

and road turns is done by means of purely conditioned reflexes;

afterwards nothing whatever of the journey will be recalled.

The efficiency of the brain as a computer is truly remarkable.

Penfield observed that the continual functions of the normally

active mind were apparent in such journeys. (56) But he emphasized that it is the mind that must first

program the computer brain, sin computer is only a thing and,

on its own, has no ability to make totally new decisions for

which it is programmed. (57)

Wonderful though the brain is as

a computer, we see its limitations and its dependence upon the

conscious directives of the mind for purposeful levels of activity

normal to human life. It is indeed something the individual possesses

but not something that possesses the individual.

Penfield was led to believe that

only what the mind has "attended to" is apparently

programmed into the brain. (58) If the subject has walked through traffic, consciously

observing avoidance patterns for maintaining his own safety,

this motor activity will be programmed in the computer automatically

and in the event of epileptic automatism the subject, though

wholly unconscious, will still navigate safely through traffic

unless some previously unexperienced complication arises. Penfield

described the normally healthy person as an individual who goes

about his world constantly depending on his own personal computer

which he programs to fit into his own continually changing objectives

and concerns. (59) *

56. Ibid., p.45.

57. Ibid., p.47.

58. Ibid., pp.39-40, 58-59.

59. Ibid., p.61.

*It should, however, be noted that under hypnosis some

recall of details that are only with difficulty attributed to

attentive observation in the past is possible. For example, under

hypnosis a man drew accurately every lump and grain on the top

surface of a brick he had laid in a wall twenty years before.

Since his trade was bricklaying, it is difficult to believe he

consciously attended to the surfaces of each brick he laid day

by day. Ralph Gerard. who reported this instance, in which the

accuracy of reporting was verified because the building was being

demolished, observed, "Men remember and recall innumerable

details never consciously perceived" ("What is Memory?"

Scientific American, September 1953, p.118). It seems

unlikely that we consciously perceive all that

idly strikes our senses. But there is no way of knowing this.

Possibly the past is not recoverable in its entirety if only

because we would need a second lifetime to recover it, and much

of it is worthless.

pg.6

of 12 pg.6

of 12

Penfield

made many surprising discoveries about the potential of temporal

lobe exploration in this way. A particular site when contacted

by the electrode produces a specific recollection. It is so specific

that the re-lived experience begins always at precisely the same

point in the sequence of events. There is not a continuation

where the last scene finished off, but a repeat performance.

In one subject this occurred sixty-two successive times! (60) This seems to indicate

a very specific localization within the cortex, like setting

the needle down in the same spot on a record. (See Figures 4

and 5)

However, it was not always so.

One subject, stimulated in the same area, had four apparently

unrelated experiential responses. First he heard "footsteps";

secondly, "a company of people in the room"; thirdly,

"like being in a gymnasium"; and finally, "a lady

talking to a child at the seashore." (61) In the case of repetitious recall, nothing has been

lost, nor has anything been added. As Penfield says, "Events

are not a bit fancifully elaborated as dreams are apt to be when

recalled." (62)

And again, elsewhere, Penfield wrote:

(63)

The vividness or wealth of detail

and the sense of immediacy that goes with its evoked responses

serves to set them apart from the ordinary process of recollection

which rarely displays such qualities. Thus with stimulation at

Point No. II in subject J. V. (Case No. 15) the patient said,

"There they go — yelling at me. Stop them!"

The individual

is able consciously to identify the meaning of the re-lived experience

not as a kind of hallucination but as something as real as life

from which he nevertheless stands apart. A woman listening

60. Penfield, Wilder and Phanor Perot, "The

Brain's Record of Auditory and Visual Experience: A Final Summary

and Discussion," Brain, vol.86, part 4, December,

1963, p.685.

61. Ibid., p.682.

62. Penfield, Wilder, "Epilepsy; Neurophysiology and Some

Brain Mechanisms Related to Consciousness," in Basic

Mechanisms in Epilepsies, edited by. Jasper, Ward, and Pope,

Toronto, Little, Brown, 1969, p.796.

63. Penfield, Wilder and Phanor Perot, "The Brain's Record

of Auditory and Visual Experience: A Final Summary and Discussion,"

Brain, vol.86, part 4, December, 1963, p.679.

pg.7

of 12 pg.7

of 12

to an orchestra

under Penfield's stimulating electrode hummed the tune she heard,

verse and chorus, thus accompanying by an act of conscious effort

the very music which was being recalled so vividly. Such recallings

were entirely involuntary. They are not memories voluntarily

brought to the surface. They are detailed and more vivid than

such memories ever are. Penfield reports the experience of one

patient who experienced an occasion on which she was sitting

in a room and listening to the children playing outside. The

sounds of motor traffic and all the other noises of urban living

provided the "natural" background. She discussed all

this with Dr. Penfield while it was happening, and so real was

the experience that it took some time to convince her afterwards

that he had not actually arranged the whole thing, including

the noises outside at the time. Needless to say, he had not done

so. (64)

Sometimes the re-lived experience

is so complex that the patient has to explain the background

of it later. One 23-year-old woman re-lived what she called a

"fabulous" event when she smashed a plate at dinner

with her elbow and tremendously enjoyed the experience! (65) She wanted to explain

why she so enjoyed it. Another patient suddenly found herself

sitting in the right-hand rear seat of a car, with the window

slightly down, waiting at a level crossing for a train to pass.

She could even count the train cars as they went and all the

characteristic sounds and noises were there. After the train

had passed and they crossed the tracks into town, even an old

familiar smell was experienced — the odour of brewing coffee.

Penfield says this was the only case of a re-experienced smell

he came across in over a thousand patients whose brain surface

was exposed in this way in an effort to locate the cause of epileptic

attacks. (66)

Figure 5. Summary maps to indicate where,

in the two cerebral hemispheres,

experiential responses of all types

were produced by electrical stimulation.

64. Ibid., pp.645—46.

65. Ibid., p.643.

66. Ibid., pp.648—49.

pg.8

of 12 pg.8

of 12

Figure 4. Diagram of the brain of one of Penfield

's epileptic patients. (Top: right hemisphere, side view; bottom:

right hemisphere, bottom view.) The letters A-F identify points

on the brain stimulated by means of an electrode. The verbal

responses of the patient to such stimulation are given below.

Reaction of patient upon contact at individual points as shown

in Figure 4.

A: "I heard something, I do not know what it was."

A: (repeated without warning) "Yes. Sir, I think

I hear a mother calling her little boy somewhere. It seemed to

be something that happened years ago." When asked to explain

she said, "It was somebody in the neighbourhood where I

live." Then she added that she herself "was somewhere

close enough to hear."

B: "Yes. I heard voices down along the

river somewhere — a man's voice and a woman's voice calling.

. . I think I saw I river."

C: "Just a tiny flash of a feeling of familiarity

and a feeling that I knew everything that was going to happen

in the near future."

D: (a needle insulated except at the tip was inserted

into the superior surface of the temporal lobe, deep in the fissure

Sylvius, and the current was switched on) "Oh! I had the

same very, very familiar memory, in an office somewhere. I could

see the desks. I was there and someone was calling to me, a man

leaning on a desk with a pencil in his hand."

I warned her I was going to stimulate, but I did not do so.

"Nothing."

E: (stimulation without warning) "I had a little

memory someone in a play — they were talking and I could

see it — I was just seeing it in my memory."

pg.9

of 12 pg.9

of 12

Penfield found that if the cortical area which had

been the site of stimulation for the re-living of some experience

was subsequently removed surgically (when it was believed to

be for the benefit of the epileptic patient), the patient could

still voluntarily recall the experience afterwards. Evidently

the memory itself was not at this point but was stored in some

area to which the site was connected. Cutting the connection

made it impossible to obtain recall by electrical stimulation,

but it did not eradicate the memory itself which could still

be recalled voluntarily.

Penfield was forced to conclude

that, while he had spent years trying to explain the mind totally

on the basis of brain-action, his years of study made it far

simpler and more logical to explain mind and brain as two basic

elements instead of one. This proposition seemed to offer the

best path to lead scientists to a final understanding of the

brain/mind issue. He believed it would never be possible to explain

the mind from neuronal action within the brain, since the mind

seems to develop independently throughout a person's life as

if it were a continuing thing and since a computer, which the

brain is, must have a controlling agency capable of independent

comprehension. (67)

Penfield has never suggested that

mind can get along without the brain, though clearly brain can

continue for some time without mind, as it does in epileptic

automatism. But the mind is the agent that programs the brain,

that decides what engrams [an engram is a memory trace]

shall be encoded in the computer for future retrieval.

Brain Does Not Account for Mind

As Penfield pointed out, and as

the monist would expect, if man's being consists of only one

fundamental element, then brain neuronal action must account

for everything that the mind does. (68) But in that case is there not some evidence of specific

neuronal activity corresponding to the thinking that the

individual is doing? To this Penfield answers no. Such evidence

had

67.Penfield, Wilder, The Mystery of the

Mind, Princeton University Press, 1975, p.80.

68. Ibid., p.78.

pg.10

of 12 pg.10

of 12

not been found in any

of his patients. Yet he is careful to admit that there may be

such neuronal activity not yet demonstrated. Moreover, he has

observed that substantial areas of the cerebral cortex can be

removed without any loss of consciousness by the subject even

during the operation, a fact which suggests that consciousness

is not specifically localized.

He summed up his conclusions by

emphasizing that his own surgical experience never revealed any

area of matter in which local epileptic discharge resulted that

might be described as mind-action.* (69)

Since

there is no evidence for such action, Penfield concluded that

the only explanation must be that there is indeed another basic

element and another form of energy, that as a programmer acts

independently of his computer, even if he depends on the computer's

action for certain things, so the mind seemingly can act independently

of the brain. (70)

If the dualistic view is never

explored, we shall never design experimental tools to uncover

the mechanism of interaction between the two elements. It before

seems logical to allow dualism as a working hypothesis and to

see whether new avenues of approach to the problem may not be

invented in the more open climate that such an allowance would

generate. Penfield was convinced we must broaden our hypothetical

base.

In this spirit he then turns to

a consideration of some more subtle and perhaps more fundamentally

important questions that the evidence invites us to ask. He

*The question of whether there is an actual

memory trace in the form of RNA specifically relating to each

memory is still an open one. The experimental evidence that planaria

which have learned some avoidance action have a particular RNA

which, when fed to untaught planaria, gives them a head start

in the learning is still a matter of debate. See for further

reading: Arlene L. Harty, Patricia Keith-Lee, and W. D. Morton,

"Planaria: Memory Transfer Through Cannibalism Reexamined,"

Science, vol.146, 1964, p.75; Allan L. Jacobson et

al., "Planarians and Memory," Nature,

vol.209, 1966, p.599—601; G. Ungar and L. N. Irwin, "Transfer

of Acquired Information by Brain Extracts," Nature, vol.214,

1967, p.435—55; Ejnar J. Fjerdingstad, Chemical Transfer

of Learned Information, New York, Elsevier, 1971; R. M. Yaremiko

and W. A. Hillix, "Reexamination of the Biochemical Transfer

of Relational Learning," Science, vol.179, 1973,

p.305.

69. Ibid., pp.77—78.

70. Ibid., pp.79—80.

pg.11

of 12 pg.11

of 12

points out that the

history of the mind's development during life as opposed to the

brain's course of development is rather different. (71) For example, if one plots

a curve showing the excellence of human performance, one sees

that the body's performance (and the brain's) improves

with time as maturing takes place, until after a certain stage

in life when a decline begins to set in and ultimately senility.

By contrast, the mind reveals no characteristic or inevitable

decline. In fact, in old age it reaches toward its fullest potential

of understanding and judgment, while the body and the brain are

slowing and sometimes failing to perform. (72)

He makes a final observation that

he had worked as a scientist trying to prove that the mind was

accounted for by the brain and, demonstrating as many brain mechanisms

as possible, he hoped to show how it was thus explained.

He ends his reflections by saying: (73)

In the end I conclude that there

is no good evidence, in spite of new methods, such as the employment

of stimulating electrodes, the study of conscious patients, and

the analysis of epileptic attacks, that the brain alone can carry

out the work that the mind does. I conclude that it is easier

to rationalize man's being on the basis of two elements than

on the basis of one.

Such, then,

is the much examined and carefully stated opinion of a man who

has had perhaps more first hand experimental knowledge of the

data than any other person at the present time.

71. Ibid., p.86.

72. Ibid., p.87.

73. Ibid., p.113.

pg.12

of 12 pg.12

of 12

Copyright © 1988 Evelyn White. All rights reserved

Previous Chapter Next Chapter

|