|

Abstract

Table of Contents

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Epilogue

Response

Further Reading

|

The Mysterious Matter of Mind

Chapter Three

Whence Came Mindedness?

That we

have something we call self-consciousness we cannot doubt even

if we find it difficult to define precisely. J. R. Smythies (Department

of Psychiatry, University of Edinburgh) wrote in 1969: "The

consciousness of other people may be for me an abstraction, but

my own consciousness is for me a reality." (12) That animals below man

have consciousness seems clear enough. That they have self-consciousness

is not so clear, in spite of the recent experiments in teaching

the larger primates some form of sign language.

Further experiments with a chimpanzee

have revealed that it was able to identify itself in a mirror

as indicated by self-directed behaviour. This is taken by some

to demonstrate the possession of self-consciousness. But it may

be necessary to distinguish between the self-consciousness of

man by which he is aware of his own mental experience

and the self-consciousness of an animal by which it is aware

of its own body. The former seems clearly different from

the latter.

12. Smythies, J. R., "Some Aspects of

Consciousness," in Beyond Reductionism, edited by.

Arthur Koestler and J. R. Smythies. London, Hutchinson Publishing

Group, 1969, p.235.

pg.1

of 14 pg.1

of 14

The San Francisco Chronicle (21

July, 1968) reported the case of a chimpanzee in the Chessington

Zoo in England which, having been for years a show-off of and

fun-loving friend of the public, suddenly became shy and morose

and took to hiding all day. The keeper decided that it was embarrassed

because the hair on its head was thinning! It was provided with

a toupee and this seemed to restore its "self-confidence"

completely. But, again, one must ask, "Is this kind of body-awareness

to be equated with the mind-awareness that permits a person

not only to think, but to think about his own thinking?"

Zoologist W. H. Thorpe (Cambridge),

a recognized authority in this area, wrote in 1974: "Sir

Karl Popper agrees, I think, with most students of animal communication

that consciousness of selfhood, that is, a fully self-reflective

consciousness, is absent in animals." (13)

David Bidney (of the Graduate School,

Indiana University) opens his study of Theoretical Anthropology

with the following: (14)

Man is a self-reflecting animal

in that he alone has the ability to objectify himself, to stand

apart from himself, as it were, and to consider the kind of being

he is and what it is that he wants to do and to become. Other

animals may be conscious of their affects and the objects they

perceive; man alone is capable of reflection, of self-consciousness,

of thinking of himself as an object.

Whether animals

do have self-consciousness or not, there is at least no doubt

that both animals and man have consciousness. Thus, even if we

limit ourselves to consciousness as opposed to self-consciousness,

we still have to ask, How did it arise?

Stanley Cobb suggests that consciousness

is an attribute of mind, that part which has to do with awareness

of self and environment. It varies in degree from moment to moment

in man, and from fish to man in phylogeny. It may be that invertebrates

and even plants have rudimentary forms of awareness of self.

(15) This sounds

absurd. But if consciousness evolved from non-consciousness,

we should find, as we trace its development back to the properties

of matter alone, that it becomes less and less manifest until

it no longer

13. Thorpe, W. H., Animal Nature and Human

Nature, London, Methuen, 1974, p.310.

14. Bidney, David, Theoretical Anthropology, New

York, Columbia University Press, 1953, p.3.

15. Cobb, Stanley, quoted by A. I. Hallowell, "Self,

Society, and Culture in Phylogenetic Perspective," in Evolution

After Darwin, edited by Sol Tax, Chicago, University of Chicago

Press, 1960, vol.2, p.348.

pg.2

of 14 pg.2

of 14

appears to exist: or,

in reverse, we should trace the development of matter until evidence

of mindedness first emerges and is manifest. Such a manifestation

would be a "new thing" (a de novo) but not a

creation (ex nihilo) because it arises out of what already

exists and without discontinuity

It is important to distinguish

a "novelty," which arises suddenly but has its origin

within an existing system, from a "new thing" which

has been introduced from outside the system. The first is something

de novo, the latter is something ex nihilo. Since

science cannot deal successfully with the latter, the idea of

outright creation is not allowable. Within the framework of scientific

thinking an object which is claimed to be ex nihilo is

suspect, and a determined effort will be made to show how it

can be derived from what already exists, however complex and

novel it may appear to be. If mind arises de novo as an

entirely new thing in nature, perhaps as the result of a mutation

of some kind, it is nevertheless assumed that it is to be derived

directly from what is already in existence. The idea of something

new which has appeared ex nihilo, that is to say, out

of nothing, is most unwelcome in the present climate of scientific

thought.

We therefore have two basic views

about the origin of mindedness, one of which is acceptable in

spite of the mystery surrounding it, because it is derived out

of existing matter. This is termed monism. The other view,

which sees it as a direct creation, not derived out of existing

matter but "out of nothing,'' is termed dualism. It

is not scientifically respectable.

We may, however, make a further

division of the subject by recognizing that within the strictly

monistic view mindedness might arise de novo in two different

ways. It might arise by slow emergence until it suddenly becomes

recognizable as mindedness. Or it might appear by a single leap

as soon as the complexity of the brain had reached a certain

critical stage. The first is a gradual formation of a mindedness

that was "always there" but at such a low level as

not to be recognizable. This is the position of panpsychism,

which holds that all matter has mindedness. The second is

a sudden appearance of mindedness which

pg.3

of 14 pg.3

of 14

thereafter has an existence

in its own right, but born of existing matter nevertheless.

Dualism can also be conceived as

occurring in two ways. Mindedness may be introduced ex nihilo

in kind of embryonic form which does not reveal itself until

a certain stage of organic development has been reached. Or it

is introduced ex nihilo only when the advanced stage of

development has been completed

Thus, although we have four alternatives,

they can be viewed as two: monism and dualism. We may thus say

that mindedness arose because matter contained within itself

the potential for it; or we may say that it was introduced

by some means external to matter. Either view presents a dilemma

which has been recognized for a long time. In one case we must

say that even atoms have potential mindedness — a circumstance

which is difficult to conceive. Or we have the direct creation

of something out of nothing — which is equally difficult

to conceive. We face a hard choice.

In 1964 Cyril Ponnamperuma wrote

a paper on "Chemical Evolution and the Origin of Life"

in which he argued that "life is only a special and complicated

property of matter, and that au fond [basically] there

is no difference between a living organism and lifeless matter

. . ." (16)

This implies that consciousness, which emerged out of living

matter, must therefore also have been latent in non-living

matter.

This sparked some interesting correspondence

in subsequent issues of the journal which had a bearing on the

point. One of the correspondents, D. F. Lawden (University of

Canterbury, New Zealand) remarked: (17)

If consciousness is a characteristic

of this material aggregate (the brain), then by the principle

of continuity it must also be a feature of every aggregate and

ultimately of the fundamental particles. If this were not the

case, at some level in the hierarchy * mentioned earlier, consciousness

would arise discontinuously and it would be possible to draw

a sharp dividing line separating conscious from non-conscious

forms of matter. This would only be a disguised form of the line

earlier assumed to

16. Ponnamperuma, Cyril, "Chemical Evolution

and the Origin of Life," Nature, vol.201,1964, p.337.

17. Lawden, D. F., in Letters to the Editor under Biology, Nature,

vol.202, 1964, p.412.

* i.e., "from inorganic, to organic, to biological chemistry."

pg.4

of 14 pg.4

of 14

pg.5

of 14 pg.5

of 14

separate living from non-living forms.

Undoubtedly, such mental characteristics as are possessed by

the fundamental particles must be of poor quality and weak intensity,

but unless some such features are postulated, I fail to understand

how consciousness could ever arise in any system of matter, however

complex.

A system of particles, each of

which possesses the known physical characteristics of electric

charge, spin, etc., might very well be designed to behave like

a human being, but not to experience consciousness as

human beings undoubtedly do. . . . We may perhaps hope

to explain human behaviour, but our experience of this

behaviour will remain unaccounted for. [emphasis mine]

There, then,

is the problem: our mindedness of our own behaviour. . . . Where

and how did it arise? Was "mind" introduced as something

entirely new, or did it emerge simply because matter had reached

the appropriate level of organization and had the appropriate

capacities?

Furthermore, when we speak of reaching

the appropriate level of organization, what precisely does this

involve? Do carbon atoms have mindedness, either real or latent?

How much organization of organic chemicals is necessary to support

mindedness? There is evidence that some of the very simplest

organisms display its presence.

H. S. Jennings long ago (1915)

established the reality of "mindedness" in unicellular

organisms. So clearly did he perceive this mindedness in amoebae,

for example, that he had no hesitation in describing them as

exhibiting attention, desire, frustration, established habits,

and even intelligence. He wrote: (18)

Intelligence is commonly

held to consist essentially in the modification of behaviour

in accordance with experience. If an organism reacts in a certain

way under certain conditions, and continues this reaction no

matter how disastrous the effects, we say that its behaviour

is unintelligent. If on the other hand, it modifies its behaviour

in such a way as to make it more adequate, we consider the behaviour

to this extent intelligent. It is the "correlation of experiences

and actions" that constitute, as Hobbhouse (1901) has put

it, "the precise work of intelligence." It appears

clear that we find the beginnings of

18. Jennings, H. S., Behavior of the Lower

Organisms, Columbia University Biological Series 10,New York,

Columbia University Press, 1915, p.334.

pg.6

of 14 pg.6

of 14

such adaptive changes of behaviour even

in the Protozoa.

So, as far as

the objective evidence goes, Jennings would hold to a complete

continuity between the [minded] behaviour of lower and higher

organisms in this respect. (19) He concluded: (20)

The writer is thoroughly

convinced after long study of the behaviour of the amoeba, that

if it were a large animal, so as to come within the everyday

experience of human beings, its behaviour would at once call

forth the attribution to it of states of pleasure and pain, of

hunger, desire, and the like, on precisely the same basis as

we attribute these things to a dog.

J. Boyd Best

found exactly the same wide range of minded responses in experiments

with planarian worms, and concluded: (21)

One finds that planarian behaviour

resembles behaviour that in higher animals one calls boredom,

interest, conflict, decision, frustration, rebellion, anxiety,

learning and cognitive awareness. . . . All one knows of

the "mind" of another organism is inferred from its

behaviour and its similarity to one's

own. . . .

If the major psychological patterns

are not unique to the vertebrate brain but can be produced even

by such primitive animals as planarians, two possibilities suggest

themselves. Such patterns may stem from some primordial properties

of living matter, arising from some cellular or sub-cellular

level of organization rather than nerve circuitry. . . .

An alternative is that behavioural

programs may have arisen independently in various species by

a kind of convergent evolution.

We are thus

led to the conclusion that even the material substance

of the single-celled animal already has a kind of embryonic mindedness.

Does all matter therefore have some kind of mindedness?

Arthur O. Lovejoy, in his Great

Chain of Being, (22) observed that one of the

principal motives of panpsychism is the desire to avoid any kind

of real discontinuity, the independent introduction of any new

thing into matter as soon as it has reached a certain level of

organization capable of supporting it. This can apply equally

to life or to mindedness. He pointed out

19. Ibid., p.335.

20. Ibid., p.336.

21. Best, J. Boyd, "Protopsychology," Scientific

American, February, 1963, p.62.

22. Lovejoy, Arthur O., The GreatChain of Being, New York,

Harper and Row, 1960, p.276.

pg.7

of 14 pg.7

of 14

that the French Philosopher,

J. -B. -R. Robinet, in his magnum opus De La Nature

(published from 1768), argued that we must either attribute

appropriate form of consciousness even to stones, some level

of intelligence even to the least atom of matter, or we ought

to deny the reality of consciousness altogether. (23)

Twenty-five years ago, Sir Julian

Huxley, driven by this kind of logic, observed: (24)

It would have been more correct

to speak of the possibilities inherent in the world-stuff * (than

in matter per se); for the most startling potentiality

revealed by evolution is mind, and mind cannot be said to be

tamed, even as a potentiality, in matter. In most organisms —

all plants, and all animal types produce the early stages of

evolution — there is no direct evidence of mind at work,

no need to postulate mental property. But higher animals are

clearly the seat of mental process akin to ours, processes of

perception, cognition, emotions, will, and even insight.

We must conclude that the world-stuff

possesses not only material properties, but rudimentary potentialities

mental properties as well, and that these properties, when specialized

out of their latent state into actuality, are of advantage to

their possessors. . . .

In most processes, the mind-aspects

of the world-stuff are still as undetectable as were the electrical

aspects material processes up to the late nineteenth century.

So the

problem of the origin of mind now descends to the stuff of the

molecules themselves. That molecules could carry some form of

embryonic mind seems absurd, but it is necessary to assume some

such potential unless we are to agree that mindedness arises

ex nihilo. Indeed, this situation appears even in the

developing embryo. That molecules do have some kind of proto-mindedness

has been seriously proposed in recent years by a number of writers,

among whom may be listed A. N. Whitehead, C. Hartshorn, Bernard

Rensch, and L. C. Birch. These writers — Whitehead and Rensch

in particular — ascribe some rudimentary

23. Robinet, -J. -B. -R., De La Nature,

Paris, 1776, vol.4, p.11—12.

24. Huxley, Sir Julian, "Genetics, Evolution and Human Destiny,"

in Genetics in the Twentieth Century, edited by L. C.

Dunn, New York, Macmillan, 1951, pp.604—5.

* By "world-stuff" Huxley does not seem to mean matter

in some even more elemental form, but energy of some kind —

though no personal energy such as a divine immanence.

pg.8

of 14 pg.8

of 14

form of life, sensation,

and even volition to entities such as molecules, atoms, and subatomic

particles. (25)

One of Dobzhansky's senior colleagues, E. W. Sinnott, with whom

he disagreed (though amicably), wrote a volume entitled Cell

and Psyche: The Biology of Purpose. In this Sinnott remarked

(26)

. . . that biological organization [concerned with organic

development and physiological activity] and psychical activity

[concerned with behaviour and leading to mind] are fundamentally

the same thing. To talk about mind in a bean plant . . .

is more defensible than trying to place an arbitrary point on

the evolutionary scale where mind, in some mysterious manner,

made its appearance. [emphasis his]

Logically

he seems to be quite correct. It is logical enough if

mind emerges automatically from brain at some stage in the elaboration

of matter. But Dobzhansky held that this is "a kind of vitalism

made to stand on its head." (27) Perhaps it is. However, it seems that if mindedness

did not emerge automatically from brain, we ought to be able

to locate the precise moment of its emergence. What would location

of the precise moment of this emergent mindedness signify if

there were no discoverable antecedents? A creation?

It would seem that Dobzhansky was

prepared to allow that life would emerge automatically

as soon as matter reached an appropriate stage of organization,

and that consciousness would arise automatically, in its turn,

when life reached a certain stage of complexity. What he was

not prepared to agree to was that this matter was already in

some sense alive, or that this life was already in some sense

conscious of itself. There was no force acting upon dead matter

to introduce life; it was only necessary that matter by chance

reached the necessary stage of organization. And there was no

necessity for some external force to act upon life to make it

conscious of itself; it only required that life should have arisen

to some higher level in order to become conscious automatically.

What he objected to was the "always there" concept.

Mindedness is seen as a new phenomenon, but it is not something

introduced from outside, a creation ex nihilo, which had

to wait until matter could provide a proper vehicle for it.

25. Dohzhansky, Theodosius, in "Book

Reviews," Science, vol.175, 7 January, 1972, p.49.

26. Sinnott, E. W., Cell and Psyche: The Biology of Purpose,

Chapel Hill, University of North Carolina Press, 1950, p.48—50.

27. Dobzhansky. in "Book Review's," p. 49. DOC

pg.9

of 14 pg.9

of 14

In another paper Dobzhansky restated his assessment

of this "always there" position: (28)

Non-living matter, down to atoms

and electrons, supposedly partakes of vital and volitional powers.

In his imposing philosophical system, Whitehead has developed

this view in some detail. . . . I must say that in my opinion

[such] views must be rejected both on scientific and philosophical

grounds.

Yet on logical

grounds one seems indeed to be on the horns of a dilemma. Just

as in the case of life itself, either consciousness arose because

the raw materials have the potential to give rise to it, or it

arose ex nihilo from outside the system.

C. H. Waddington (of Edinburgh),

reviewing Rensch's work, Evolution Above the Species Level

(1959), notes that the author (29)

. . . finds himself driven to attribute a capacity for sensation

to the lowest organized creatures which can be shown to be capable

of learning, that is, coelenterates and possibly even protozoa.

He seems, in fact, to agree in general with the outlook of A.

N. Whitehead (to whom he does not refer) that something which

belongs within the same realm of being as consciousness has

to be attributed to all existing things, including the inanimate.

[emphasis mine]

It was the same

logical compulsion that drove Sir Charles Sherrington to write:

(30)

I would think that since mind

appears in the developing soma, this amounts to showing that

it is potential in the ovum (and sperm) from which the soma sprang.

The appearance of recognizable mind in the soma would then be

not a creation de novo but a development of mind from unrecognizable

into recognizable. [emphasis mine]

By this logic

we come to the position of Whitehead and Rensch. One then has

to ask, What was the form of this proto-mindedness that it could

be potentially resident not only in the basic subatomic particles

but even in these particles at a time when they were existing

at the enormously high temperatures of their initial state as

first brought into being? Somewhere one has to call a halt and

say, Here is where proto-mind began to

28. Dobzhansky, Theodosius, "Man Consorting

with Things Eternal," in Science Ponders Religion,

edited by H. Shapley, New York. Appleton-Century-Crofts. 1960,

pp.120—21.

29. Waddington, C. H., Book Reviews, Discovery,1960, p.453.

DOC

30. Sherrington, Sir Charles, Man on His Nature, Cambridge

University Press, 1963, p.251.

pg.10

of 14 pg.10

of 14

exist. But where then

did it come from to make that beginning even in its proto form?

When the Mindedness of Individual Cells

Becomes a Shared Mindedness of the Multicellular Organism

Once mindedness

or consciousness has appeared on the scene in unicellular animals,

does the rest follow automatically? When single-celled

organisms unite to form multicellular aggregates, does the proto-mindedness

of the amoeba become the corporate mindedness of the larger mass?

Is Lovejoy's "great chain" still unbroken?

Sherrington identified this problem

in the developing embryo: (31)

The embryo, even when its cells

are but two or three is a self-centered cooperating society —

an organized family of cells with corporate individuality.

The human individual is an organized

family of cells, a family so organized as to have not merely

corporate unity but a corporate personality. . . . Yet

each of its constituent cells is alive, centered in itself, managing

itself. feeding and breathing for itself, separately born and

destined separately to die.

Evidently this aggregate or society achieves

a sense of unification and the billions of selves becomes a single

Self. Edward McCrady wrote some time ago: (32)

I, for instance, certainly have

a stream of consciousness which I, as a whole, experience, and

yet I include within myself millions of white blood cells which

give impressive evidence of experiencing their own individual

streams of consciousness of which I am not directly aware. It

is both entertaining and instructive to watch living leukocytes

crawling about within the transparent tissues of a living tadpole's

tail. They give every indication of choosing their paths, experiencing

uncertainty, making decisions, changing their minds, feeling

contacts, etc., that we observe in larger individuals. . . .

So I feel compelled to accept the

conclusion that I am a community of individuals who have somehow

become integrated into a higher order of individuality endowed

with a higher order of mind which somehow coordinates and harmonizes

the activities of the lesser individuals within me.

31. Ibid., p.65.

32. McCrady, Edward, Religious Perspectives of College Teaching

in Biology, New Haven, Connecticut, Edward W. Hazen Foundation,

1950, pp.19—20.

pg.11

of 14 pg.11

of 14

How is this unification achieved? Most would say that

it somehow does it itself. Sir Alister Hardy believes it is the

result of some kind of group-mind, of mental telepathy at a very

basic and semi- or sub-conscious level. He wrote: (33)

It is possible to imagine

some such pattern of shared unconscious experience: a kind of

composite species pattern of life. It is important to remember

that in the concept of the individual mind we are faced with

a mystery no less remarkable. The mind cannot be anchored to

this or that group of cells that make up the brain. The community

of cells making up the body has a mind beyond the individual

cells — the "impression" coming from one part of

the brain receiving sensory impulses from one eye and that from

another part of the brain from the other eye are merged together

in the mind (i.e., as a whole), not in some particular cells

as far as we know.

Lewis Thomas

has a beautiful discussion of this gathering together to a critical

size of the number of minded components that then make a fully

conscious and purposeful whole. (34)

Termites are even more extraordinary

in the way they seem to accumulate intelligence as they gather

together. Two or three termites in a chamber will begin to pick

up pellets and move them from place to place, but nothing comes

of it; nothing is built. As more join in, they seem to reach

a critical mass, a quorum, and the thinking begins. They place

pellets atop pellets, then throw up columns and beautiful, curving,

symmetrical arches, and the crystalline architecture of vaulted

chambers is created. It is not known how they communicate with

each other, how the chains of termites building one column know

when to turn toward the crew of the adjacent column, or how,

when the time comes, they manage the flawless joining of the

arches. The stimuli that set them off at the outset, building

collectively instead of shifting things about, may be pheromones

[scent given off by one animal to signal to another] released

when they reach committee size. They react as if alarmed. They

become agitated, excited, and then they begin working like artists.

Even more closely

knit in organization is the conglomerate of free living cells

which constitutes the Portuguese Man-of-War. This organism is

really a

33. Hardy, Sir Alister, The Living Stream,

London, Collins, 1965, p.257.

34. Thomas, Lewis, The Lives of a Cell, New York, Viking,

1974, p.13.

pg.12

of 14 pg.12

of 14

colony of originally

identical polyps, each of which is specialized for a particular

function. But who or what decides which shall become the tentacles,

or the floats, or the reproductive organs? And this Man-of-War

is by no means alone in this respect.

Recent experiments have shown that

healthy organs that have been teased apart will re-assemble and

show themselves to be, within the limitations of their isolated

condition, functional. It has been demonstrated for frogs' eggs,

(35) brain cells,

(36) heart cells,

(37) and kidney

tissue. (38) It

has even been reported that cells which prove to be deficient

in some way in the re-assembly process will be helped along if

necessary by healthy cells. (39) Such a system of communication and co-ordination

of activity suggests an organizing force or "field"

of some kind (these words being used not because they explain

anything but because they appear to cover our ignorance of what

is going on).

So we see the possibility of mindedness

in an individualistic form in the very lowest orders of life,

and we see individualistic mindedness elaborated in conglomerates

of cells which are able to communicate and constitute themselves

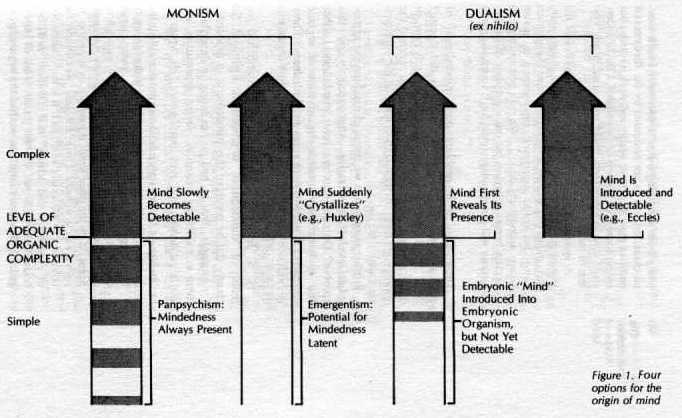

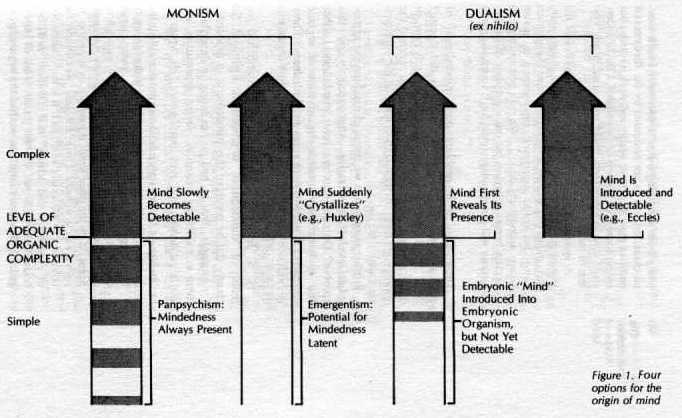

into a larger form of mindedness. Nevertheless, the basic problem

of whence arose mindedness, even in the unicellular forms, still

remains behind all the later complications. We thus have the

three possible views (see Figure 1): the panpsychic or "always

there" view, the "sudden emergence view," and

the "introduction of mind by creation ex nihilo view"

(with its two forms).

We have already referred to a remarkable

volume written jointly by Sir Karl Popper and Sir John Eccles.

Together they have examined, somewhat in the form of a debate,

both the origin of mindedness and the nature of the interaction

between mind and brain.

Both men reject panpsychism and

agree that man ends up constitutionally as a duality of mind

and matter, each of which has a measure of real independence

and each of which interacts with the other.

Popper argues against the necessity

of assuming that mind has been "always there" in matter.

"We do not need to postulate," he says, "that

the food which the body eats (and which in the end may form its

brain) has

35. Montagu, Ashley, On Being Human,

New York, Henry Schuman, 195), p.34.

36. Seeds, Nicholas and Albert E. Vetter, Proceedings of the

National Academy of Science, vol.68, p.3219; L. W. Lapham

and W. R. Markesbury, "Human Fetal Cerebellar Cortex: Organization

and Maturation of Cells in Vitro," Science, vol.173,

27 August, 1971, p.829—32.

37. Harary, Isaac, "Heart Cells in Vitro," Scientific

American, May, 1962, pp.141—52.

38. Weiss, Paul, and A. C. Taylor, "Reconstruction of Complex

Organs from Single Cell Suspensions of Chick Embryos in Advanced

Stages of Differentiation," Proceedings of the National

Academy of Science, vol.46, September, 1960, p.177—85.

39. Chedd, Graham, "Cellular Samaritans," New Scientist,

31 October, 1968, p.256.

pg.13

of 14 pg.13

of 14

qualities which can

be, with informative success, described as pre-mental or as in

any way even distantly similar to mind." (40) All that is required is that matter has the capability

of assuming a form that is appropriate to mindedness and that

when this occurs mindedness somehow appears.

Eccles holds that mind cannot be

introduced until matter is sufficiently organized. But he argues

that the organization of the individual as a unitary self out

of the materials of the body is due to the self-conscious mind

which neither is in the materials themselves nor arises out of

them but is introduced from outside. The minded self is an active

organizer that brings about unification and employs this unified

system for its own purposes.

Both men are therefore dualists,

though they hold differing views as to the origin of the

mind. For Popper, matter somehow gives birth to mind;

this is all that can be said about it. For Eccles, the origin

of the mind seems more like a creation ex nihilo for each

individual.

Before exploring their conclusions

more fully, we turn to the experimental evidence that led them

to accept an interactionist model.

40. Popper, Sir Karl and Sir John Eccles,

The Self and Its Brain, Springer Verlag International,

1977, p.69.

pg.14

of 14 pg.14

of 14

Copyright © 1988 Evelyn White. All rights reserved

Previous Chapter Next Chapter

|