|

Abstract

Table

of Contents

Part I

Part II

Part III

Part IV

Part V

Part VI

|

Part I: Historical Survey

Chapter 5

Calvin And Calvinism

Throughout this

whole controversy there runs a single thread, rooted in human

pride and demanding the right to be personally responsible in

the decision-making process at some critical point in the conversion

experience. Many men desire to be saved, or say they do, until

they discover that God's way makes them entirely dependent upon

his grace, thus discounting completely any supposed merits they

may have counted upon to improve their chances of being saved.

Such are they who would take the Kingdom by force (Matthew 11:12).

*

The Gospel is that we are saved

by faith alone without works of any kind, not even the working

up of ourselves into a state of readiness or willingness to be

saved, nor even the exercise of our own faith. Here is the heart

of the matter. This is the "offense of the Gospel"

(Galatians 5:11). Salvation is all of God; and since it is clearly

a selective process (for only some are saved), it must be a sovereign

act of God's Election. Man can neither choose to be saved nor

can he initiate the process.

The issue is whether we are called

upon to co-operate in helping God (or conversely to ask God to

help us), or whether we are simply clay in the hands of the Potter.

Clay has no say. Reason tells us that we ought to be able to

co-operate if we wish; pride tells us that we do co-operate.

We offer our own willingness, or non-resistance, something of

ourselves at least, anything of ourselves will do no matter how

small it is. The

* In Luke 13:24 the Lord seems to speak of

many who "will seek to enter in and shall not be able,"

as though men did indeed desire salvation but were refused. The

answer to this apparent anomaly seems to lie in the fact that

these many individuals did indeed wish to enter in � but

on their own terms. Like the man who crashed the gate of the

wedding and sat down to enjoy the feast � but without the

appropriate wedding garment, such improper entry can result only

in being rejected as soon as the King discovers their presence

(Matthew 22:11-13). It is interesting to see that the individual

in this little story knew perfectly well he was in the wrong

place and had no excuse. He was speechless. And it is also significant

perhaps that it was by this little story that the Lord introduced

one of the most famous of all passages to be quoted in connection

with Election: "For many are called, but few are chosen"

(verse 14).

pg

1 of 13 pg

1 of 13

great thing is that it

is of ourselves. As autonomous beings we demand the right of

making some essential contribution. It need not be much �

but it must be essential.

Many, with all the self-assurance

in the world, come loaded with good things to be credited to

their account. The poorer souls may seem to come more humbly,

but they too hug the only possession they have to offer, their

own willingness. It is quite possible to be as proud of this

as it is of a large account. Surely this is as great a thing,

seeing their circumstances, as the goods their affluent neighbours

can bring along! Certainly it is as offensive to the soul to

have a humble contribution (humble by force of circumstance)

set aside as it is for the affluent man to have his set aside.

Pride is a mighty assertive force, and rather than cause offense,

ministers all too frequently yield to pressure and adulterate

the Gospel. It must be embellished, added to, completed by the

pitiful works of man.

This adulteration, this challenge

to the perfect sufficiency of the Lord's sacrifice, is technically

termed by theologians "the evil leaven of synergism."

Synergism is a word which means "joint-effortism."

If there is one pervasive theme above all in Calvin's system

of theology it is this: Solus Deus. God alone! God alone

is man's Saviour; the act of regeneration is monergistic, a solo

work of God without man's help in any way whatsoever.

Many years ago Warfield put it

this way: (1)

Thus it comes about that monergistic

regeneration � "irresistible grace," "effectual

calling," our older theologians called it � becomes

the hinge of Calvin's soteriology [i.e., doctrine of salvation],

and lies much more deeply embedded in the system than many a

doctrine more closely connected with it in the popular mind.

Indeed, the soteriological significance

of predestination itself consists to the Calvinist largely in

the safeguard it affords to the immediate supernaturalness of

salvation. What lies at the heart of this soteriology is absolute

exclusion of creaturely efficiency in the induction of the saving

process, in order that the pure grace of God in salvation may

be magnified.

Only so could he express his sense

of man's complete dependence as a sinner on the free mercy of

a saving God; or exclude the evil leaven of synergism by which

God is robbed of his glory and man is encouraged to attribute

to some power, some act, some initiative of his own, his participation

in that salvation which in reality has come to him from pure

grace.

The controversy

as carried forward by men like Gottschalk was essentially the

same, but there was a different emphasis. Predestination to Election

was the basic theme, not the grace of God as the sole means whereby

that Predestination is realized in the life of the individual.

Grace alone: this

1. Warfield, Benjamin B., Calvin as a Theologian

and Calvinism Today, London, Evangelical Press, c.1909, pp.16f.

pg.2

of 13 pg.2

of 13

is really Calvin's message.

All else in his theology is subservient and derivative. Indeed,

to Calvin, as to Owen and Spurgeon and a host of other spiritual

giants of subsequent generations, this was the one theme that

held all else together. Once admit man's spiritual deadness and

total ineptitude in the matter of his salvation and everything

else follows. Once abandon this, and the whole Christian system

becomes indefensible and fragmented. Spurgeon wrote of Calvinism:

"I have my own private opinion that there is no such thing

as preaching Christ and Him crucified unless we preach what is

called nowadays Calvinism. It is a nickname, to call it Calvinism.

Calvinism is the Gospel and nothing else." (2)

Now John Calvin was born on June

10, 1509, at Noyon in Picardy. Like so many other young men who

became great warriors in the Lord's service, he had a notably

devout mother. His father was quite well off and had sufficient

influence with the ecclesiastical authorities that he could secure

for his son certain benefices that allowed him a higher education

and professional status. John had set himself to become a Man

of Letters par excellence.

Unlike Augustine, Calvin was a

quiet student and his youth a blameless one seriously devoted

to his calling. But he was an individualist and had no tendency

to become a mere rubber stamp reiterating the words and phrases

of his teachers. He was open-minded and affectionate and, contrary

to the stern picture we tend to have of him in later life, he

had a genuine and refreshing sense of humour as some of his letters

show. By the time he was twenty-two he was an established humanist

scholar, settled in Paris, with a well-earned reputation through

his publication in 1532 of a commentary on a treatise by Seneca

(c. 8 B.C.�A.D. 65) entitled On Clemency.

And then due chiefly to the influence

of men like Ulrich Zwingli (1484�1531) and Martin Bucer (1491�1551),

who had been greatly influenced by Luther, the whole direction

of his life and interests changed. In due course he was solidly

converted, the exact circumstance not being altogether clear.

From that time, Calvin had no doubt that his goal was now henceforth

to be a Man of Letters for God. And his pen became busy at once,

but his forthrightness soon made it unwise for him to remain

in France where there was a growing pressure against Protestants.

He fled to Basel.

In the spring of 1536 he published

what he variously referred to as "An Apology," "A

Manifesto," and a "Confession of Faith." It was

a brief document of less than a score of pages. It is not altogether

certain but it is generally believed that this was a first draft

of what was to become the Institutes of the Christian Religion.

Although it was brief, the title certainly was not. It read:

The Institutes of the Christian Religion,

Containing almost the Whole Sum of Piety and Whatever It

is Necessary

2. J. I. Packer, Introductory Essay in John Owen, The Death

of Death in the Death of Christ, London, Banner of

Truth trust, 1959 reprint, [1852], pp.10f.

pg.3

of 13 pg.3

of 13

to Know in the Doctrine of Salvation.

A Work Very Well Worth Reading by All Persons Zealous for Piety,

and Lately Published. A Preface to the Most Christian King of

France, in which this Book is Presented to Him as a Confession

of Faith. Author, John Calvin, of Noyon (Basel, MDXXXVI)

Three years

later he expanded his "little book" into an ample treatise

on theology. The question of the precise relationship of these

works and whether the 1539 issue was indeed merely an expansion

of the 1536 draft is in some doubt. But this was certainly the

beginning of his worldwide influence as a Reformed theologian

and a Man of Letters for God. As already indicated, Predestination

had only brief treatment in his initial statement. It was not

a key issue at this point in the development of Calvin's theology.

The key issue was the grace of God.

After some moves back and forth

between Geneva, Basel, and Strassburg, he began almost reluctantly

an active ministry that kept him from his beloved books more

than he wished but resulted in the establishment out of a group

of French refugees like himself the first "model Church"

under his shepherding.

It was at Strassburg that his literary

activity as a truly great Man of Letters really began, and it

was from Strassburg that at thirty years of age he published

the more elaborate form of his original "little book."

Such was the prolific output of his pen subsequently that it

was to require fifty-nine volumes to contain all the "Works

of John Calvin."

In 1559 he published the definitive

edition of his Institutes, probably the most influential

single work on Dogmatic Theology ever to have been written after

the close of the New Testament Canon. The works of Augustine

were certainly as influential, but they did not in quite the

same way constitute a single thesis. As Benjamin Warfield put

it: (3)

As the first adequate statement

of the positive program of the Reformation movement, the Institutes

lies at the foundation of the whole development of Protestant

theology, and has left an impress on evangelical thought which

is ineffaceable. After three centuries and a half, it retains

its unquestioned pre-eminence as the greatest and most influential

of all dogmatic treatises.

The same writer

underscores the debt which Calvin owed to Augustine. Calvin's

doctrine of the Church was not his own creation, though he gave

it a precision and vitality that was truly a reformation. It

was his doctrine of grace that was so peculiarly his own as to

be called thereafter Calvinism rather than Augustinianism.

Yet as Warfield says: (4)

It was Augustine who gave us

the Reformation. For the Reformation, inwardly considered, was

just the ultimate triumph of Augustine's doctrine

3. Warfield, Bejamin B., Calvin

and Augustine, edited by amuel Craig, Philadelphia, Presbyterian

& Reformed Publishing Co., 1971, p.8.

4. Ibid., p. 322

pg.4

of 13 pg.4

of 13

of grace over Augustine's doctrine of

the Church. This doctrine of grace came from Augustine's hands

in its positive outline completely formulated: sinful man depends,

for his recovery to good and to God, entirely on the free grace

of God; this grace is therefore indispensable, prevenient, irresistible,

indefectible; and being thus the free grace of God, must have

lain in all the details of its conference and working in the

intention of God from all eternity.

Now the so-called

Five Points of Calvinism, which were not really Calvin's to begin

with though truly representative of his theology, were formulated

implicitly by Augustine, who drew his inspiration for them from

Paul. All through the centuries thereafter down to Luther's time

these same five points have been argued over, denied, believed,

explored, written about, and misunderstood. Whether man is totally

depraved and spiritually dead or only very sick*, whether Election

is based entirely on God's pleasure or on foreseen merit, whether

the sacrifice of Christ is intended for all men or only for the

elect, whether men can or cannot resist the grace of God, and

whether the saints are eternally secure in their salvation or

can fall away and be lost again: these are the basic issues of

debate in the theology of salvation. Calvin did not put an end

to the debate but he so crystallized the issues, and showed so

compellingly the logic of their relatedness, that it has ever

since been understood by the truly informed that they all stand

or fall together. And Calvin showed why they all stand or fall

together. He set forth in lucid terms the logical consistency

and coherence of the doctrine of Sovereign Grace and showed that,

granted any one of these Five Points, the rest must follow inevitably:

deny any one of them and the whole structure is endangered. One

cannot satisfactorily defend some points but not others.|

Charles Hodge has a

beautiful summary of the heritage that belongs to Reformed theology.

(5)

Such is the great scheme of

doctrine known in history as the Pauline, Augustinian, or Calvinistic,

taught, as we believe, in the Scriptures, developed by Augustine,

formally sanctioned by the Latin Church, adhered to by the witnesses

of the truth during the Middle Ages, repudiated by the Church

of Rome in the Council of Trent, revived in that Church by the

Jansenists, adopted by all the Reformers, incorporated in the

creeds of the Protestant Churches of Switzerland, of the Palatinate,

of France, Holland, England, and Scotland, and unfolded in the

Standards framed by the Westminster Assembly, the common representative

of Presbyterians in Europe and America.

* Pelagius said man is well; Augustine

said man is dead: Arminius said man is sick.

5. Charles A. Hodge, Systematic Theology, Grand Rapids,

Eerdman's, `973 reprint [1871-73], vol.II, p. 333.

pg.5

of 13 pg.5

of 13

When

people today think of Predestination they associate it with Calvinism.

This is unfortunate for it far antedated Calvinism and is one

of the few doctrines about which there has been almost universal

agreement in all the Churches. There is not the same agreement,

of course, as to its precise meaning; nor is there the same agreement

as to its basis. But as a fact of Christian theology it has not

been challenged. It is also unfortunate that it should be so

closely associated with Calvinism because it is only one facet

of Calvinism and not the central one. It is a logical element

in the doctrine of Sovereign Grace but it is a consequence rather

than a cause. The cause of our Election lies in the good pleasure

of God and the ground for it is not Predestination but the full,

perfect, and sufficient sacrifice of the Lord Jesus Christ. Election

is a necessity because man is so spiritually dead that the Lord's

sacrifice would never have become effectual but for the Sovereign

Grace of God. Had his sacrifice merely been offered to man it

would never have been accepted. And foreknowledge has nothing

to do with Election because there is nothing good in man to be

the grounds of that foreknowledge except negatively.* The only

thing that God could foresee was that man would never be able

to turn to Him for salvation unless He Himself first turned man.

As the Psalmist said: "Quicken us and we will call upon

your name. Turn us again, O LORD God of hosts . . . and we shall be saved" (Psalm

80:18, 19). If man is to be saved at all, God must not only provide

the means but undertake the entire initiative in making those

means effectual. If anything is left to man there is no hope.

Man is totally dependent because he is totally depraved, and

unless God predestines some and elects them to be saved, man

is entirely without hope. Salvation is all of grace and that

grace is sovereign. Such was the burden of Calvin's message.

John T. McNeill, who has provided

an Introduction to the English edition of Calvin's works published

in Philadelphia by Westminster Press in 1960, seeks to correct

a commonly held view that Calvin's mind was a kind of factory

turning out and mechanically assembling the parts of a neatly

jointed structure of dogmatic logic. (6) Throughout his work it is manifest that, like Augustine,

Calvin's heart and mind were in beautiful balance. The spiritual,

emotional, and intellectual aspects of his being were joined

in the effort. He was not a professional theologian but a deeply

religious man who made warm friends and who also happened to

possess a genius for orderly thought. "The secret of his

mental energy," McNeill wrote, "lies in his piety."

The first great object of his pen was to make the way of salvation

* In the matter of Double Predestination,

some theologians have seen Predestination to Reprobation as based

entirely on foreknowledge of guilt.

6. John T. McNeill, Introduction, in John Calvin, Institutes

of the Christian Religion, Philadelphia, Westminster Press,

1960, p.Ii.

pg.6

of 13 pg.6

of 13

plain; the second was

to persuade men to believe it; the third was to encourage the

elect to adorn their faith by their lives.

In order to deal in depth with

Calvin's doctrine of salvation, it is appropriate first of all

to examine the circumstances which led to the formulation of

the so-called Five Points to which reference has already been

made. As will be seen these Five Points did not originate with

Calvin's pen but with those who opposed his doctrine. Nevertheless

they provide a very good starting point for a consideration of

the structure of Calvin's theology of salvation.

Throughout the whole controversy

between grace and works, between synergism and monergism, between

the Total Depravity of man and a residue of natural human goodness,

between divine sovereignty and human responsibility, there was

always a concurrent issue the solution to which is probably one

of God's secrets, but it is an issue which has refused to go

away. This was the question of Double Predestination, a question

which has kept cropping up throughout the history of Christian

thought. It will be remembered that the term originally meant

that men were divinely predestined either to be saved or to be

lost. The assumption was made that if some were predestined to

be saved then the rest of mankind was automatically predestined

to be lost and God was accordingly accused of injustice. Augustine

held it in the sense that the sinner is, by reason of the very

moral fabric of the universe, destined (and so predestined) to

suffer the consequences of his guilt, or predestined to be saved

from those consequences by the sacrifice of Christ. One or the

other is necessarily man's destiny. But while God clearly knows

beforehand what is to happen in every individual instance, it

is not necessary to assume that this foreknowledge means that

it was also his intention that many should be lost. It can just

as easily mean that man is allowed to suffer the consequences

of his guilt as a sinner and is therefore predestined to reprobation,

a reprobation which God clearly foresees and foreknows. (7) It is a case of divine

permission of a certain course of events predetermined by the

very structure of the moral order. God gave man free will and

in Adam man made his choice freely. Thereafter human nature prefers

the course of action which leads to destruction. Man chooses

destruction as a free expression of his fallen nature and God

allows him this choice. The end result is that man by nature

is predestined to reprobation but the foreknowledge of God relative

to this fact is not the cause of it.

On the other hand, Election to Salvation

is causative because man's will, freely expressed, would not

otherwise allow Election to Salvation to be effectual. Thus Predestination

to reprobation is caused by man; Predestination to salvation

is caused by God. The first is a natural consequence of the

7. Berkhof, Louis, History of Christian

Doctrines, Edinburgh, Bannr of Truth Trust, 1975 reprint,

[1937], p.136.

pg.7

of 13 pg.7

of 13

will of man; the last

is a supernatural consequence of the will of God. Yet both may

fairly be described as "predestined" events.

Thus the situations are essentially

different. The Predestination which is the natural consequence

of man's corrupted will is self-fulfilling, inevitable, in one

sense uncaused except by the spiritual laws which God has built

into his universe. But there was always a tendency to confuse

these two very different kinds of Predestination. The concept

of Predestination was taken to mean the same thing in both cases,

thus making God responsible for man's unhappy destiny. God became

in fact the author of sin. And those who thus understood Calvin's

view on the matter could justify this position (as Zanchius did)

by an appeal to certain passages in Scripture which can be interpreted

to support it. Calvin himself never seems to have been quite

able to make up his mind on the matter. He seems in certain

places to be teaching Double Predestination (he called it Decretum

Horribile, an awful decree), by arguing that God really planned

that man should fall in order to work out his divine purposes

to his own glory by the saving of a certain number of the fallen.

The important point here is that God so planned before He

created man. He did not first create man, permit him freedom

of choice, and therefore leave the way open for the Fall to occur.

God made his plan before creating man and then, being sovereign,

determined that this plan should be followed. Calvin said, "It

is an awful decree, I confess. . . . God not only foresaw

the Fall of the first man and the ruin of posterity in him, but

arranged all by the determination of his own will" (Institutes,

III.xxiii.7). It may well have been pointed out to Calvin that

his reasoning here was of doubtful validity for it would surely

be just as true to say, "God foreknew what end man was to

have (if and when he fell) before creating him, because He had

so ordained reprobation to be the inevitable consequence of disobedience."

What God did was to allow man to fall; but man having fallen,

God then predetermined what would be the consequences.

In his study of Calvin's doctrine

of Predestination, F. H. Klooster notes Calvin's assertion that

there could be no Election to Salvation without its opposite,

Election to reprobation (Institutes, IlI.xxiii.1), and

adds with propriety, "This assertion is not a logical deduction."

(8) I believe he

is right.

If a group of guilty men are in

prison for their crimes and one is reprieved by the decree of

a State Governor, it is not the State Governor's decree in freeing

the one man that caused the other men to remain in prison. They

remain in prison because they have not yet completed their sentence.

They remain in prison because they are in prison to begin

with, and under judgment not yet fully satisfied. Men who do

not believe in the Lord are not condemned because they do not

believe; they are condemned already (John 3:18) and simply

remain so.

8. Klooster, F. H., Calvin's Doctrine

of Predestination, Calvin Theological Seminary Monograph

Series III, Grand Rapids, Calvin Theological Seminary, 1961,

p.36.

pg.8

of 13 pg.8

of 13

If

I hold a golf ball in my hand it does not fall. Because I am

holding it, I am in the strictest sense the cause of its not

falling. If I let it go, nature takes its appointed (predestined)

course and it falls. It is only in a manner of speaking that

it falls because I let it go. The real reason that it falls is

gravity. In a spaceship, away from the gravitational forces of

the earth, I could let it go and it would not fall. If I throw

it down I am contributing directly to its fall, but if I let

go of it I am not a direct cause of its falling. The principle

is a very wide one, and it is very easy to use language loosely

and therefore to confuse the issue.

These two alternative effects of

Predestination both appear to be grounded in the same phenomenon,

the intention of God. But they are not really so at all. Predestination

to Salvation is causative, the will of God being the cause of

salvation; Predestination to Reprobation is consequential, reprobation

being the consequence of the disobedience of man. The first is

therefore the result of God's intention, the second of God's

permission. It should be pointed out perhaps that by this circumstance

those who find themselves in heaven have only God to thank, whereas

those who find themselves under judgment have only themselves

to blame. To make the analogy of the men in prison complete,

one might therefore say with equal propriety that the one who

was reprieved has only the Governor to thank, whereas the ones

who were left in jail have only themselves to blame.

Calvin quotes Matthew 15:13, "Every

plant which my heavenly Father has not planted shall be rooted

up," and comments on this by saying that the hearers are

being "plainly told that all whom the heavenly Father has

not been pleased to plant as sacred trees in his garden are doomed

and devoted to destruction" (Institutes, III.xxiii.1).

The implication here is quite specific. Those who do not reside

in Paradise are not of God's planting. God is not the author

of such trees. For this reason they do not belong in the garden.

Thus the analogies we have used above are reflected in Scripture

by implication if nothing else. For the divine Gardener did not

plant these foreign trees in the first place. It is as though,

like weeds, they had planted themselves.

It seems clear that Calvin's own

logical mind sensed the illogic of Double Predestination and

yet never quite succeeded in resolving the issue to his own satisfaction.

J. L. Neve in his History of Christian Thought says: "Calvin

did not express himself clearly or consistently on this matter."

(9) Certain passages

in Calvin's writings can be quoted in favour of Double Predestination

and others against it. This caused some dissension and disagreement

among his followers. A scholarly layman, D. V. Koornheert of

Holland, wrote against this teaching, and demanded that the Belgic

Confession, which incorporated it, be revised. Jacob Arminius

(1560�1609), known for

9. Neve, J. L., History of Christian Thought,

Philadelphia, Muhlenberg Press, 1946, vol.II, p.16.

pg.9

of 13 pg.9

of 13

his dialectic skill

and for his loyalty to Calvin, was invited to reply to him. But

the effect of the studies which Arminius made in preparation,

carried out specifically to formulate his rebuttal, converted

him to a non-Calvinistic position! * He turned against the whole

system of Calvinistic theology, perhaps because he realized for

the first time that there was no room for any kind of sentimental

humanist acknowledgment of man's innate goodness, a discovery

which he did not like. He became so actively hostile that a serious

schism arose affecting the whole Reformed Church in Holland.

Though Arminius

died in 1609, his followers produced a number of able spokesmen.

These met together in 1610 and drew up the Statement of Faith

setting forth the grounds of their opposition to Calvinism and

their alternative interpretation of the whole question of Predestination,

foreknowledge, and Election. Their Articles were called Remonstrances,

and they themselves were accordingly called Remonstrants.

The Calvinists issued a counter statement, but to no good purpose.

So the matter was introduced before the famous Synod of Dort

in 1618 at which representatives were present from England, Scotland,

the Palatinate, Hesse, Nassau, East Friesland, and Bremen.

The representatives of Arminianism

were treated with great discourtesy, and the Five Articles of

their Remonstrance were condemned. Five Calvinistic canons

were drafted and the Belgic Confession and the Heidelberg

Catechism were formally adopted. In spite of the rather unlovely

procedure, the end result was a magnificent Statement of Faith

that eloquently reflected Calvin's theology.

The Five Articles of the Remonstrance

have ever since served as one of the most effective backdrops

against which to set the Reformers' position. They may be summarized

in the following way. They are here arranged not in the original

order in which they were presented but to reflect the order in

which they were answered.

(1) The Fall left man spiritually very sick but

not in a state of total incapacity. He still has some freedom

to good. His will is not entirely enslaved to a sinful nature.

He needs only God's assistance in his coming to conversion. In

this he brings his own faith and his own willingness.

(2) Accordingly, Election is based upon foreknowledge.

God foresees who will be willingly disposed and who will

refuse, and elects those whom He knows will assent. If some oversimplification

is permitted it might be said that Arminians held that God's

foreknowledge related to those who would seek salvation. In the

Lutheran system this foreknowledge related to those who would

not resist God's call. In the Methodist system God's foreknowledge

related to those who He knew would persevere.

* An excellent and sympathetic biography of

Arminius has been written by Carl Bangs, Arminius: A Study

of the Dutch Reformation, New York, Abingdon Press, 1971.

pg.10

of 13 pg.10

of 13

(3) Christ died for all men, for

the salvation of all men was God's original plan. It is not God's

will that any should perish but, having been given freedom, man

is able to accept or reject salvation and only a few are saved.

(The fourth point was joined to this third point, though these

two points are generally set forth as two separate articles.)

(4) Man is entirely free to resist the grace of

God.

(5) Even after yielding to God and accepting the Lord as

Saviour, a man may so resist the influence of the Holy Spirit

thereafter in his life that he becomes a castaway, a reprobate,

disapproved, "turning again to his former wallowing,"

and so in the end losing his salvation.

It will be obvious

that these Five Points of the Arminian Remonstrance have

the same kind of logical coherence as the system of Calvin does.

One point follows from the other and all hold together in a kind

of organic unity, granted the premise. The premise of the Remonstrance

is that man is able to contribute to his own salvation because

he is not totally depraved, and that God requires this contribution

to make salvation effectual. From this it follows that man can

subsequently cease to support his part of the bargain so that

the work of God then fails in its objective and man is finally

lost. Since the sovereignty of God in salvation is thereby surrendered

and his predeterminate elective purposes can no longer be considered

the cause of man's salvation and perseverance, Election is the

result simply of foresight relative to the individual's anticipated

response.

The crux of the matter in these

two logical (or theological) systems is the Sovereignty (or otherwise)

of the Grace of God, and its co-ordinate � the freedom (or

otherwise) of the will of man, determining his own destiny. It

has been rightly said that evangelism based on Calvinism lays

the emphasis on the Sovereign Grace of God; evangelism based

on any form of Arminianism is dependent upon man's powers to

persuade. The world has developed highly successful techniques

of high-pressure advertising in the hands of the so-called Persuaders,

and Arminian evangelism has tended to adopt many of the same

tactics. Power lies with man and must be applied with maximum

effect, as in all advertising the emphasis is often laid more

on the method than the message.

Although the great Confessions

of the Reformed Churches (Thirty-Nine Articles, Westminster,

Heidelberg, and so forth) are Calvinist, and although ministers

in the denominations that once drew their inspiration from these

Confessions are therefore Calvinist by profession, the great

majority of them have long since adopted an Arminian approach

to evangelism and depend far more upon techniques of persuasion

than upon the truth of their professed Reformation theology.

There is today a great need for a return to the Gospel of Sovereign

Grace as the sole remedy for man's Total Depravity.

These two streams of theology,

the Calvinist on the one hand, and the

pg.11

of 13 pg.11

of 13

Semi-Pelagian-Arminian-Lutheran-Methodist

on the other, seem always to have existed side by side within

the household of faith almost from the day the Church was born.

Undoubtedly God uses both streams to create saints and to forge

their characters. But in many important ways there can never

really be complete fellowship between the Lord's people in the

two camps. The basic premise of each is so totally opposed to

the other and its effect so pervasive on each system of thought

that conversation quickly deteriorates into argument as soon

as it becomes seriously involved with fundamental issues. As

long as we remain at a superficial level we can praise the Lord

together. But one is aware always of skating together on thin

ice. Since such arguments can never be wholly resolved unless

both parties adopt the same basic premise there can never be

real reconciliation. If the logical constructs in each system

were simply abandoned there might be hope of reconciliation,

because equally illogical adjustments would either pass unnoticed

or would not disturb those who employed them. But such is man's

constitution that irrational thinking never really proves an

adequate base for peace of mind or heart. Fellowship

on such grounds is always a fragile thing on the edge of collapse

if some unexpected thought should intrude itself. Guarded conversation

is not conducive to openness of heart which is essential to true

fellowship.

And so we seek desperately to "sink

our differences," and this serves merely to produce a unity

among us which is theologically emasculated and powerless to

challenge a sinful world.

Having set the

historical background in some perspective, we now turn to an

in-depth study of these two Five-Point alternatives

to see what Scripture has to say on the matter.

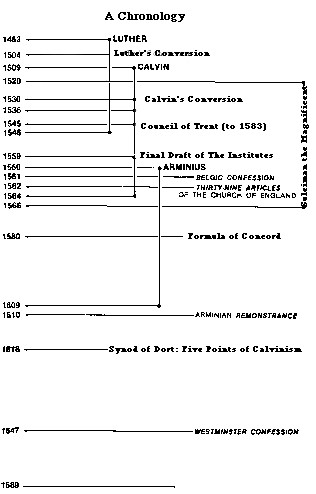

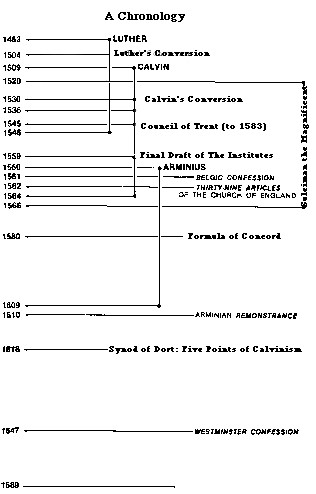

The chronological table below will

help the reader to see the historical relatedness of the events

we have outlined.

pg.12

of 13 pg.12

of 13

pg.13

of 13 pg.13

of 13  Copyright © 1988 Evelyn White. All rights

reserved

Previous Chapter Next

Chapter

Copyright © 1988 Evelyn White. All rights

reserved

Previous Chapter Next

Chapter

|