|

About

the Book

Table of Contents

Part I

Part II

Part III

Part IV

Part V

|

Part III: Convergence and the Origin

of Man

Chapter 3

The Implication

of Convergence on Human Origin

IT IS well known that the human skull

is plastic enough that it may, in the adult stage, be modified

towards a more ape-like form if the eating habits of the ape

are simulated in one way or another by man. The question bears

examination because many of the skulls of early man have undoubtedly

been deformed in the direction of the ape skull for what Portmann

(59) would have termed "historical" (as opposed

to genetic) reasons. Such deformation can occur within a single

lifetime. It is, of course, not inherited by the offspring, but

if the conditions of life persist over several generations, chances

are that a few skulls will be preserved as fossils whose configuration

might give the impression that their owners were not far removed

by descent from an ape-like sub-human ancestor, whereas, in point

of fact, no such relationship need be postulated.

Wilson

D. Wallis observed years ago: (60)

The evidence

of prehistoric human remains does not in itself justify the inference

of a common ancestry with the apes. We base this conclusion on

the fact . . . that practically all the changes in man's structure

traceable through prehistoric remains are the result of changes

in food and habit.

The most notable changes are found

in the skull. Briefly the story of changes is to: a higher frontal

region, increased bregmatic height, smaller superciliary ridges,

increased head width, less facial projection, decreased height

of orbits and a shifting of the transverse diameter downward

laterally, a more ovoid palate, smaller teeth, diminished relative

size of the third molar, shorter, wider and more ovoid mandible,

decrease in size of condyles, decrease in distance between condylar

and coronoid processes, and in general greater smoothness, less

prominent bony protuberances, less of the

59. Portmann, A., "Das

Ursprungsproblem," Eranos-Jahrbuch, 1947, p.19: "One

and the same piece of evidence will assume totally different

aspects according to the angle -- palaeontological or historical

-- from which we view it. We shall see it either as a link in

one of the many evolutionary series that the paleontologist seeks

to establish, or as something connected with remote historical

action. . . . Let me state clearly that for my part, I have not

the slightest doubt that the remains of early man known to us

should be judged historically."

60. Wallis, Wilson D., "The Structure of Prehistoric Man"

in The Making of Man, edited by V. F. Calverton, Modern

Library, Random House, New York, 1931, pp.69ff.

pg

1 of 11 pg

1 of 11

angularity and

"savageness" of appearance which characterizes the

apes. This is evolution in type, but the evolution is result

rather than cause, . . .

Practically

all of these features of the skull are intimately linked together

so that scarcely can one change without the change being reflected

in the others, some features, of course, reflecting the change

more immediately and more markedly than do others. If we suppose

that man's diet and his manner of preparing food have changed,

we have an index to most of the skull changes, provided that

the dietary change has been from uncooked or poorly cooked to

better cooked food, and from more stringent to less stringent

diet. Development of stronger muscles concerned with chewing

will bring about the type of changes which we find as we push

human history further back into the remote past.

Change is

most marked in the region in which chewing muscles function.

With tough food and large chewing muscles is associated a large

mandible with broad ramus, large condyles, heavy bony tissue.

. . . Larger teeth demand more alveolar space and there results

a more prognathous and more angular mandible. The more forward

projection of the teeth in both upper and lower alveolar regions

is in accordance with the characteristics of animals which use

the teeth for the mastication of tough food, and no doubt is

a function of vigorous mastication.

The adjacent

walls of the skull are flattened and forced inward as well as

downward, producing the elongation of the skull. The temporal

muscles reach far up on the skull, giving rise to a high temporal

ridge: they extend forward as well as backward, giving a more

prominent occipital region, and a more constricted forward region,

resulting on the forehead region of the skull in the elevation

of the superciliary ridges and intervening glabellar region.

Projecting brow ridges are associated with stout temporal and

masseter muscles and large canines.

The facial

region is constricted laterally and responds in a greater forward

projection, one result being that the transverse diameter of

the orbits is thrust upward outwardly, giving the horizontal

transverse diameter which characterizes the apes and which is

approximated in pre-historic men and in some contemporary dolichocephalic

(long headed) people. In young anthropoid apes, when chewing

muscles are little developed and there is little constriction

in the lateral region posterior and inferior to the orbits, the

transverse diameter of orbits is oblique as in man, being elevated

to the horizontal, when temporal muscles develop and function

more vigorously, thrusting in and upward the outer margin of

the orbits. Constriction of outer margins of orbits produces

the high orbits which we find in apes, and to a less marked degree

in prehistoric human remains.

One issue of

the Ciba Symposia was devoted to a study of Eskimo life. The

subject is particularly apropos in the present context because

these extraordinary people are often considered rather precise

"models" of paleolithic man. Writing in this issue,

Erwin Ackerknecht pointed out: (61)

The cheekbones

and jaws of the Eskimo are very massive, possibly under the influence

of the intense chewing he has to practice, which also results

in a

61. Ackerknecht, Erwin, Ciba

Symposia, vol.10, no.1, 1948, p.912.

pg.2

of 11 pg.2

of 11

tremendous development

of the chewing muscles. Eskimo teeth are often worn down to the

gums, like animal teeth, from excessive use.

Fig. 7 shows a characteristic Eskimo

male face, with the skull form outlined to show that the greatest

width is at the jowls and not in the temple region. The head

of Gainsborough's Blue Boy in Fig. 8 however, shows how

a refined diet tends to produce a head form of another kind with

the greatest width in the temporal region. It has been also pointed out that

the Eskimo skull occasionally shows a "keel" along

the top, which results directly from the need for a stronger

attachment or anchorage for the jaw muscles, which are used much

more extensively. This will be noted in Fig. 7, and should be

compared with the keel indicated in the skulls of three supposedly

human fossils in Fig. 9. It is very clearly marked in the case

of the gorilla skull in this illustration.

William

Howells pointed out: (62)

Gorillas

have a heavy and very powerful lower jaw, and the muscles which

shut it (which in man make a thin layer on and above the temple,

where you can feel them when you chew) are so large that they

lie thick on the top of the head, about two inches deep, practically

obscuring the heavy brow ridge over the eyes which is so prominent

on the skull, and giving rise to a bony crest in the middle merely

to separate and afford attachment to the muscles of the two sides.

In the Eskimo skull and in the gorilla

skull, there is therefore sometimes a certain parallelism, which

is in no way any indication of genetic relationship. The explanation

of the Eskimo keel is a historical (i.e., cultural) one. Again,

we quote Howells on this subject: (63)

The powerful

jaw of these animals in chewing, gives rise to a terrific pressure

upwards against the face, and the brow ridges make a strong upper

border which absorbs it.

If man is subjected to uncooked food,

and forced in the absence of knives to tear it from the bone,

the developing muscles will find a way of strengthening their

anchorage along these bony ridges. Moreover, if there is not

in the diet that which will harden the bone in the earlier years

of life when such strains are first encountered, it is inevitable

that the skull will be depressed while still in a comparatively

plastic state, and the forepart of the brain case will be low

and sloping so that it lacks the high vault we tend to associate

with cultured man. Thus the massive brow ridges of Sinanthropus,

so similar to those of Pithecanthropus, are, as Ales Hrdlicka

pointed

62. Howells, William, Mankind

So Far, Doubleday, New York, 1945, p.68.

63. Ibid., p.131.

pg.3

of 11 pg.3

of 11

Fig. 7.

Contrast the form of this Eskimo head with the head of "Blue

Boy" in Fig. 8. This drawing is based on a photo reproduced

on the cover of Ciba Symposia (vol.10, No.1) and is quite exact

in its proportions: (A) a simplified outline; (B) an ancient

Eskimo skull, showing the keel (slightly exaggerated) on the

top and the front of the head.

Fig. 8.

This head is based on Gainsborough's painting, "Blue Boy,"

and is drawn to exact scale. It shows clearly the influence of

what may be termed a cultured diet. The wide part of the head

is at the temples. (A) Cranial outline for comparison with Eskimo

head in Fig. 7. (B) Modern European skull.

pg.4

of 11 pg.4

of 11

out some

years ago, "a feature to be correlated with a powerful jaw

mechanism." (64)

Let

us assume, for the sake of argument, that early man was subsequently

forced to eat tough food, after an initial family had multiplied

and wandered apart; and that this food lacked that which would

harden the skull in its formative period of development. Then

the strengthening of the chewing and cervical muscles would go

hand in hand with building a substructure of bone to provide

the necessary anchorage in the form of crests as well as ridges

in the front, at the rear, and on the top of the skull. But the

skull itself would remain pliable enough that it would undergo

considerable distortion. The "keel" which is so noticeable

in the case of the gorilla, would naturally tend to appear in

this early man, because the muscles would pull the sides of the

skull in, under the increased tension (see Fig.10). When the

jaw was used for cracking bones, etc., the chief point of stress

would regularly occur at the chin, since the clamping action

between the teeth would normally be one-sided. This again led

to a certain degree of compensatory thickening. But unlike the

apes, man is a talking creature and makes much more use of his

tongue. There is reason to believe that the reinforcement of

man's chin takes the form of a bony ridge outwards rather than

inwards, on this account, and this gives the prominence which

is characteristic of the human jaw. The apes and other anthropoids

on the other hand have the reinforcement in the form of a ledge

which reaches inward instead. This is known as the simian shelf.

In some fossils of early man there is some evidence of a simian

shelf, and presumably this is a reinforcement in addition to

that which is normal for man's chin, by way of compensation for

the added load placed upon the structure at this point. Tugging

at flesh in the absence of satisfactory "cutlery,"

or maybe just bad table manners, possibly contributed to the

alveolar prognathism which is found in these early remains. The

increasing muscle development which rose up under the zygomatic

arch naturally forced the latter outwards and it developed a

stronger form.

It

is quite likely therefore that the functioning of the jaw mechanism

determines whether the skull will be depressed or not. The fossil

human forms then show clearly that the entire series has been

affected to a large degree by the same depressive and compressive

forces. Thus if early man were to have been utterly deprived

of culture it seems quite certain his fossil remains would have

revealed

64. Hrdlicka, Ales, Skeletal

Remains of Early Man, Smithsonian Institute, Miscellaneous

Collection 83, 1930, p.367.

pg.5

of 11 pg.5

of 11

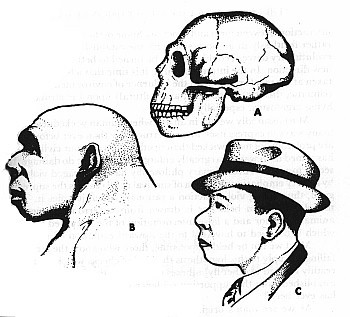

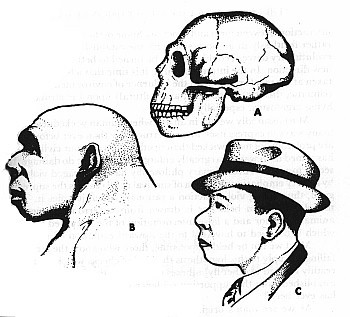

Fig. 9.

(A) Gorilla, showing marked keel and wide zygomatic arch. (B)

Modern Man with high vault and widest dimension at the temples.

(C) Pithecanthropus. (D) Rhodesian Man. (E) Sinanthropus.

Fig. 10.

Skulls of a female gorilla (left), a Pithecanthropus (center),

and a modern Papuan native (right), viewed from above. The marked

formation of the supraorbital ridge and the postorbital narrowness

are evident. Such marked differences can almost certainly be

attributed to the development of powerful muscles for chewing

and biting.

pg.6

of 11 pg.6

of 11

an extreme

primitiveness, which might easily be misinterpreted as evidence

of a recent emergence from some anthropoid stock. Yet in point

of fact, it could happen that individuals might become degenerate

at any period in history and leave behind them a cemetery of

the most deceptive fossil remains.

Humphrey

Johnson remarked in this connection: (65)

It seems

likely that in very early times the human form possessed a high

degree of plasticity which it has since lost, and that from time

to time such exaggerations of certain racial characters, probably

brought about by an unfavourable environment, have occurred.

In the Pekin-Java branch of the human family, the exaggeration

of the ape-like traits has occurred to a very high degree: it

later took place, so it would seem, though not quite so pronouncedly

in Neanderthal Man, and has occurred again though to a far lesser

extent in the aborigines of Australia.

Some of the

low features of the Australians may, as Prof. Haddon thinks,

be due to racial senility, and thus the resemblance to Neanderthal

Man may be regarded as secondary or convergent. By a wider application

of this principle we may consider that "convergence"

has played a part in bringing about the resemblance of paleoanthropic

men to the anthropoid apes.

If this interpretation of the evidence

is correct, it follows that a return to the conditions of diet

and life which characterized prehistoric man would be followed

by a tendency to move also towards his physical type. Such a

resemblance to the ape as is borne sometimes by fossil man would

in no way relate to phylogenetic descent. In a given group, the

adult male would be more likely to resemble the ape than the

infant does (and probably more than the female does, too), yet

it could not be argued on this account that the adult was more

nearly related to the simian ancestor than the infant or the

female. Franz Boas pointed this out many years ago: (66)

If we

bring two organically different individuals into the same environment

they may, therefore, become alike in their functional responses,

and we may gain the impression of a functional likeness of distinct

anatomical forms that is due to environment, not to heredity.

I have said previously that we do

not have unequivocal evidence that ape-like forms actually evolved

into more man-like forms, but we do have evidence of man becoming

physically more ape-like in cranial bone structure. Indeed, LeGros

Clark admitted that this very point has been urged quite seriously

and with some force: (67)

65. Johnson, Humphrey, The

Bible and the Early History of Mankind, London, 1947, p 89.

66. Boas, Franz: quoted by Ralph Linton, The Study of Man,

Appleton-Century, New York, 1936, p.26.

67. Clark, Sir Wilfrid LeGrow: quoted by Rendle Short, in The

Transactions of the Royal Victoria Institute, vol.66, 1935,

p.255.

pg.7

of 11 pg.7

of 11

Prof. Wood Jones

has pointed out that there are some anatomical features which

make it easier to believe that the apes are descended from man

rather than man from an extinct ape.

He

believed that evolution never retraces its steps however. Thus,

he argued that such a retrogressive step would never occur. Perhaps,

but in structural form and therefore to an uncritical eye, man

may ''regress" part of the way, though the verb "degenerate"

would be much more appropriate. Man has done this, even in comparatively

recent times, as Robert Chambers pointed out when recounting

the eventual fate of certain poor Irish peasants around 1600

who were dispossessed of their homes under particularly harsh

circumstances: (68)

The style

of living is ascertained to have a powerful effect in modifying

the human figure in the course of generations, and this even

in its osseous structure. About 200 years ago, a number of people

were driven by a barbarous policy from the counties of Antrim

and Down in Ireland, towards the sea-coast: there they have ever

since been settled, but in unusually miserable circumstances.

And the consequence

is that they now exhibit peculiar features of the most repulsive

kind, projecting jaws with large open mouths, depressed noses,

high cheek bones, and bow legs, together with an extremely diminutive

stature. These, with an abnormal slenderness of limbs, are the

marks of a low and barbarous condition all over the world.

This is not a case of a single individual,

for we have here a whole group of people whose "primitive"

appearance resulted entirely from historical circumstance. Undoubtedly

they were as far removed from the apes, by descent, as you and

I, and were potentially as educable and as intelligent as their

contemporaries. If we add cases of isolated individuals who have

become "cast out" or lost to society and yet have survived

somehow to old age, we have the ingredients of "fossil man."

Since in the nature of the case, early man began in one spot,

presumably he must have spread under some pressure as population

multiplied. At the center, where a larger number of people would

encourage the development of higher civilization, fragments would

continually be breaking away like pioneers seeking more room

and greater freedom. The first small migrant groups would tend

to retreat further and further from the centre to the periphery

as the pressures behind increased, and as they did so they would

abandon the well-tried and more familiar accouterments of civilization

with which they began and would culturally regress, just as pioneers

almost always do at first. The higher their initial estate,

68. Chambers, Robert, Vestiges

of the Natural History of Creation, Churchill, London, 1844.

pg.8

of 11 pg.8

of 11

the lower

would be their last. In time, the struggle would diminish their

resources even further, wherever the band was too small or the

environment too harsh. A few sole survivors might well perish

in frightful isolation along the leading edge of the spreading

waves, as old age rendered their continuance impossible. These,

at the periphery, may be our "fossil men," descendants

of civilized human beings, not their ancestors.

Arthur

Koestler rightly observed, (69) indeed, that longevity might well

degrade such individuals even more markedly, till, they were

quite ape-like!

Disease

can also play a part. As we know, the first Neanderthal representative

was reconstructed as a club-carrying brute creature with ape-like

stoop and a slouching gait. It is known now that this first specimen

was actually a diseased individual. (70) Subsequent

finds of Neanderthalers are known to have been quite erect in

posture. (71) And there are those who believe Mr.

Neanderthal could pass down the street quite unnoticed if he

were only correctly dressed, with a suitable haircut (see Fig.11).

Of

the effects of disease, Jesse Williams in his Textbook of Anatomy

and Physiology said: (72)

Degenerate

types show characteristic markings that are known as stigmata

of degeneration. Common stigmata are: (1) receding forehead,

indicating incomplete development of frontal lobes of the brain;

(2) prognathism, a prominence of the maxillae; (3) the Canine

ear; (4) prominent superciliary ridges; (5) nipples placed too

high; and (6) supernumerary nipples.

Glandular disturbances can likewise

have profound effects on the anatomy. Keith (73) attributed

a tendency to strong brow ridges to

69. Koestler, Arthur, The

Ghost in the Machine, Hutchinson, London, 1967, p.167: "Prolongation

of the absolute lifespan of man might provide an opportunity

for features of the adult primate to reappear in human oldsters:

Methuselah would turn into a hairy ape."

70. The first Neanderthal specimen was evidently suffering from

chronic osteoarthritis, an ailment which forced him to adopt

a stooped posture. See C. S. Coon, The Story of Man, Knopf,

New York, 1962, p.40. Coon said his "bones were rotten with

arthritis." See also the report by A. J. E. Cave at the

15th lnternational Congress on Zoology, London, noted in Discovery,

November, 1958, p.469.

71. On Neanderthals' normal erectness, Alberto Carl Blanc and

Sergio Sergi, in Science (vol.90, supplement, 1939, p.13).

These authors reported the finding of two further skulls, with

the base of one skull "well preserved, enabling Prof. Sergi

to establish for the first time that Neanderthal man walked erect

and not with the ape-like posture with head thrust forward as

previously believed. The horizontal plane of the opening in the

skull shows that the bones of the neck were fitted perpendicular

into the opening, showing the posture to be erect as in the present

day man."

72. Williams, Jesse, Textbook on Anatomy and Physiology,

5th edition, Saunders, Philadelphia, 1935, p.49, footnote.

73. Keith, Sir Arthur: quoted by Sir John A. Thompson in The

Outline of Science, vol. 4, Putnam, New York, 1922, p.1097.

pg.9

of 11 pg.9

of 11

Fig. 11.

This Neanderthal skull (A) from La Chapelle-aux-Saints was in

due course reconstructed (B) for the Field Museum of Natural

History, Chicago, to show how our primitive ancestor looked.

It was reconstructed (C) by J. H. McGregor to show how "modern"

he really might have been in appearance.

a hyperactive pituitary; whereas

underdevelopment of the pituitary may account for a certain flatness

of face observed in many European nationals. (74)

Cultural

behaviour may effect marked changes in the structure of the skull

and jaw. Tearing flesh from the bone in the absence of knives

tends not.only to strengthen the masseter muscles and enlarge

the zygomatic arch somewhat as a direct consequence, but also

to give a forward lean to the front teeth, both of which features

lend a more ape-like cast to the face. Indeed, we really have

little precise information on the extent to which bone structure

may be modified in the absence of a bone hardening diet during

infancy.

There

is much room for a fresh look at the whole question of the

74. Keith, Sir Arthur, "Evolution

of Human Races in the Light of Hormone Theory," Bulletin

of the Johns Hopkins Hospital, 1922.

pg.10

of 11 pg.10

of 11

interaction

between form and function. Some of the time being spent rather

fruitlessly in an obsession with the establishment of lines of

evolutionary descent could perhaps be turned to better account

in a new direction. In the interest of truth, it is time that

a fresh look was taken at the whole question of the influence

of environmental facts (climatic, dietetic, barometric, and culture)

upon the structure of living organisms, especially man.

Most

assuredly we live in an age when human wickedness finds many

ways to express itself more destructively than ever before: We

are probably not more wicked than in other ages, but our civilization

has armed us in ways that greatly enlarge our power to do damage.

It seems to me that evolutionary philosophy has encouraged violence

by its very emphasis on the idea of survival at all costs as

the supreme good, thus giving violent action a rationale which

justifies it. This model for human behaviour is drawn from an

erroneous view of animal behaviour and a false interpretation

of the supposed pattern which is believed to have led to the

upward evolution of all life.

Must

we not be held responsible, those who know the facts, for failing

to apply to this hypothesis the kind of checks which we apply

readily enough to other hypotheses that can be much more securely

established from the supporting evidence than evolutionary theory

has ever been?

As

we see man's origin, so we see his destiny. Evolutionary theory

is not only bad science, as I see it, but an even worse philosophy.

pg.11

of 11 pg.11

of 11  Copyright © 1988 Evelyn White. All rights

reserved

Previous Chapter *

End of Part III * Next

Chapter (Part IV)

Copyright © 1988 Evelyn White. All rights

reserved

Previous Chapter *

End of Part III * Next

Chapter (Part IV)

|