|

About the Book

Table of Contents

Part I

Part II

Part III

Part IV

Part V

|

Part V: Is Man An Animal?

Chapter 6a

The Expression of Humanness in

Man

IN THIS chapter

I draw attention to some significant factors in the development

of a human being which do not appear in the animal world. Superficially,

they look like mere extensions of animal behaviour. When analyzed

more carefully, it will be seen that they are not. If a student

begins with the assumption that he will find the explanation

of human behaviour in the animal world, he will discover in due

course that he has been mistaken. Those who have matured in their

study and have honestly faced the evidence will already have

discovered the inadequacy of such an assumption. It is in the

textbooks which are written for younger students and for the

public that the most misleading statements in this regard are

to be found. In works of a more serious nature a different picture

emerges. Let me illustrate this with a series of quotations,

before entering into a detailed consideration of this chapter

under more specific headings.

Writing in Science in 1945,

Alexander Novicoff said: (167)

Man's social relationships represent

a new level, higher than that of his biological make-up. Man's

behaviour differs from that of other animals because of his possession

of body structures, notably the highly developed nervous system,

which make thought and speech possible and whose functioning

is profoundly affected by social and cultural influences. . .

.

The study of animal behaviour cannot

be a substitute for the study of man's behaviour. As we establish

the likenesses in behavior of animals and men, we must simultaneously

investigate the fundamental qualitative differences between them.

. . . Animal societies never rise above the biological level,

only man's society is truly sociological.

Anyone who has tried to teach biological

change to college students knows the barriers to learning that

have been created by the identification of animals with men throughout

the student's lifetime.

This observation

underscores an important point. For reasons which

167. Novicoff, Alex, "The Concept of

Integrated Levels and Biology," Science, vol.101,

1945, p.212.

pg.1

of 39 pg.1

of 39

are complex, man does

not build his society along the lines of biological expedient.

Let me quote from a more recent source on this point. David R.

Pilbeam, reviewing a book by P. V. Tobias, The Brain in Hominid

Evolution, (168)

challenged his view that this unique creature, man, really emerged

in his present form because he became a toolmaker. Pilbeam felt

otherwise:

There is more to human cultural

behaviour than the ability simply to learn, or to chip flint.

Our behaviour differs from the learned behaviour of all other

animals, including chimpanzees, in such important ways as to

render descriptions of non-human primate learned behaviour as

examples of "crude and primitive culture" potentially

highly misleading.

Human cultural behaviour involves

a very special form of learning, depending upon learned rules,

norms, and values which vary arbitrarily from one culture group

to another. . . .

About the only

thing that can be said that is universally true of human behaviour

is that it is non-instinctive. As a consequence, like Cleopatra's

charms, it has "infinite variety." When you have a

single species producing an infinite variety of cultural patterns,

even where those varied patterns are found to have developed

in virtually identical environments, then you obviously have

a species that is not like any other species in nature. Bertalanffy

had this to say on the subject: (169)

According to von Uexkull's doctrine, the organization and

specialization of an animal is decisive for what enters into

its ambient world. Of the great cake of reality, an animal cuts

a slice, so to speak, of what becomes stimuli, to which it reacts

in correspondence with its inherited organization. The rest of

the world is non-existent for that particular species.

In contrast to the organization-bound

ambient of animals, "Man has a universe," to use an

expression of Gehlen. Any section of the world, from the galaxies

that are inaccessible, to direct perception and biologically

irrelevant, down to the equally inaccessible atoms, can become

an object of interest to man. . . .

Precisely because he is lacking

organic and instinctual adaptation to a specific environment,

he is able to conquer the whole planet from the poles to the

equator. So man creates his own ambient, which is what we call

human culture.

In one of the

flood of Darwin Centennial volumes which appeared from 1958 on,

Ernest R. Hilgard in Theories of Learning, observed (170)

168. Pilbeam, David, reviewing P. V. Tobias,

The Brain in Hominid Evolution, Science, vol.175,

1972, p.1101.

169. Bertalanffy, Ludwig von, "A Biologist Looks at Human

Nature," Scientific Monthly, January, 1956, p.35.

170. Hilgard, Ernest, Theories of Learning, 2nd edition, Appleton-Century,

New York, 1956, p.461.

pg.2 of 39

pg.2 of 39

There have

emerged (in man) capacities for retraining, reorganizing, and

foreseeing experiences which are not approached by the lower

animals including the other primates. No one has seriously proposed

that animals can develop a set of ideals that regulate conduct

around long-range plans, or that they can invent a mathematics

to help them keep track of their enterprises. . . .

There are probably a number of

different kinds of learning which have emerged at different

evolutionary periods, with the more highly organized organisms

using several of them. It is quite probable that these different

kinds of learning follow different laws, and it is foolhardy

to allow our desire for parsimony to cause us to overlook

persisting differences [my emphasis].

We have, then

in man a new kind of learning. In point of fact, man's kind of

learning actually leads him to ignore experience, to live in

an unreal world. No animal does this. As we shall see, because

animals learn by experience, the older animal is almost certain

to be the wiser animal. This is by no means true of man. Yet

his very foolishness has enormously enriched his experience.

In fact, it is probably the basis for one form of human behaviour

which must surely be unknown in any other animal, namely, laughter.

We can find, as we shall see, some evidence of culture in animals,

including art; and of course we find a gamut of emotions from

the sheer joy of life of the young colt or the spring lamb to

the grief of a dog which has lost its human companion. But we

do not observe laughter.

One final quotation: Clifford Geertz,

in a paper entitled "The Transition to Humanity," had

this to say: (17l)

Some students, especially those

in the biological sciences � zoology paleontology, anatomy,

and physiology � have tended to stress the kinship between

man and what we are pleased to call the lower animals. They see

evolution as a relatively unbroken, even flow of biological processes,

and they tend to view man as one of the more interesting forms

life has taken, along with dinosaurs, white mice, and dolphins.

What strikes them is continuity, the pervasive unity of the organic

wild, the unconditioned generality of the principles in terms

of what is formed.

However, students in the social

sciences � psychologists, sociologists political scientists

� while not denying man's animal nature, have tended to view

him as unique, as being different, as they often put it, not

just in degree but in kind.

Man is the tool making, the talking,

the symbolizing animal. Only he laughs; only he knows he will

die; only he disdains to mate with his mother and sisters; only

he contrives those visions of other worlds to live in which Santayana

called religions, or bakes those mud pies of the mind which Cyril

Connolly called art.

He has, the argument continues,

not just mentality but consciousness, not just needs but values,

not just fears but conscience, not just a past but a history.

Only he, it concludes in grand summation, has culture.

171. Geertz, Cliffard, "The Transition

to Humanity," in Human Evolution, edited by N. Korn

and F. Thompson, Holt, Rinehart & Winston, New York, 1967,

p.114.

pg.3

of 39 pg.3

of 39

I'm

not sure Geertz himself accepts this demarcation altogether,

but it is a beautiful summary of a position to which I subscribe

and which the rest of this chapter explores analytically. And

it leads us, in the end, to man's unique possession of conscience

and spiritual aspiration, his need for redemption and his capacity

for it, which is the subject matter of the final chapter of this

paper.

Let us, then, turn first to an

analysis of man's culture.

Home and Hearth � Uniquely

Human

All mammals

have some form of family life. The young are born in varying

states of dependence upon their parents for food, shelter, warmth,

protection against enemies, and discipline. But the period of

dependence is comparatively short, in some cases exceedingly

so, and this brevity is related to the fact that in all animals,

except man, the time to maturity relative to the total life-span

is much shorter. This seems to be governed partly by the speed

with which the young mature and become self-sufficient, and perhaps

partly because the maturing process is reached more quickly the

educatability of the young comes to an end far sooner.

The consequences of these two circumstances

are, first, that the family unit in the animal world tends to

be ethereal for any particular brood. The young are very quickly

and very deliberately ejected from the home, even from the territory,

being forced thereafter "to go it alone" and actually

being unwelcome any longer around the house, as it were. Secondly,

from experience with apes, and indeed with many other animals,

it has by and large been found that any training in performance

which is not natural to the animal must be done very early, before

the animal's brain seems to have become "crystallized."

We have noted already, the Kelloggs found that at three years

of age their experimental chimpanzee had reached her graduation

point, whereas the human subject, which was sharing the chimpanzee's

experience, was just beginning to accelerate his learning processes.

Indeed, in the normal course of events, it is likely that he

would go on learning, actively, in the sense of formal education

for perhaps another twenty years. In terms of total life-span,

the average human being is still highly teachable for from one-third

to one-half of his normal life whereas the chimpanzee does most

of his learning in what is probably less than one-tenth of his

normal life. Since learning is cumulative and not merely additive,

a program of education conducted actively for twenty years has

not merely seven times the potential of the ape, but some much

greater factor entirely.

Eric H. Lenneberg, in his study

on the physiological basis of the

pg.4

of 39 pg.4

of 39

human faculty of speech,

attributes man's ability to use language to the slow maturing

of his brain: (172)

Species differ in their embryological

and ontogenic histories. Brain maturation curves of Homo sapiens

are different from those of other primates. Man's brain matures

much slower, and there is evidence that the difference is not

merely one of a stretched time-scale, but that there are intrinsic

differences. Thus man is not born as a fetalized version of other

primates, the developmental events in his natural history are

sui generis. The hypothesis is advanced that the capacity

for language acquisition is ultimately related to man's peculiar

maturational history. . . .

Not only does

the animal's mind reach a static maturity sooner, but its whole

body reaches mature stature more rapidly. Man at birth is approximately

5 percent of his mature weight; at fourteen he is about 60 percent;

and he must reach the age of twenty before he will be 90-95 percent

of his final size. (173)

By the time they are one year, other animals will have reached

60 percent of their adult size, and by the time they are three

years old 90-95 percent of adult size. In other words, their

growth is relatively accelerated � something like seven times

compared with man. In some animals the acceleration in growth

rate is much greater than this. Samuel Brody said "Pre-pubertal

percentages of sheep and goats which have the same mature weight

as man is sixty fold that of man." (174)

Brody examined

the effects of the decelerated growth rate for man in terms of

experience and observed: (175)

The large and highly developed

brain affords reflective power and furnishes the basis for speech

and writing, the long growth period affords opportunity to learn,

and the long life span affords time to reflect and to develop

traditions, all of which are pre-requisite for the development

of religion and science.

Moreover, the long human childhood

period of dependency on parents stimulates socialization, the

rearing of children of different ages simultaneously (a uniquely

human characteristic) reinforces socialization, with charity

and tolerance on the part of the stronger towards the weaker

children, and the mental consciousness of the involved relationships

leads to the development of group morals.

Robert Briffault

emphasized the matter of slow maturing in terms of educatability:

(176)

The question is sometimes mooted

whether young gorillas or chimpanzees might not by careful training

be taught to speak. . . . The brain of the

172. Lenneberg, E. H., Biological Foundations

of Language, Wiley, New York, 1967, p.179.

173 Brody, Samuel, "Science and Social Wisdom," Scientific

Monthly, September, 1944, p.207.

175. Ibid.

176. Briffault, Robert, "Evolution of the Human Species"

in The Making of Man, edited by V. F. Calverton, Modern Library,

Random House, New York, 1931, p.768.

pg.5 of 39

pg.5 of 39

young anthropoid grows too quickly; it

is formed, it has lost its malleability before the time required

for such an education.

This was written

in 1931, long before the Kelloggs and their successors reported

their experiences. Briffault has proved to be quite correct in

his prognostications. It is true that Premack did not begin his

program of training of Sarah until she was six years old and

he had surprising success, which might seem to contradict what

we have been saying. It is possible that Sarah was an exceptional

animal. Or it is possible that if she had begun her training

in infancy, she, too, would have reached her capacity within

three years. Perhaps her brain, in so far as some kind of speech

area was involved, was in this area still "uncommitted,"

to use Penfield's apt expression. Nevertheless, the experience

of other trainers of animals which can learn to respond to human

commands bears out the statement that their learning capacity

falls off very rapidly as soon as they reached, for them, adolescence.

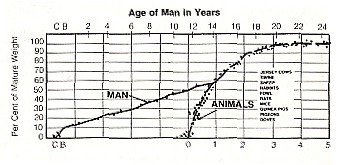

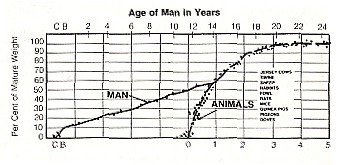

In his paper, Samuel Brody had

a scattergram (Fig. 22) showing the relative growth rate of nine

animals (cow, pig, sheep, rabbit, fowl, rat, mouse, guinea pig,

and dove) contrasted with the growth rate of man. In the interest

of simplicity, I have traced his curves but omitted all the symbols

which he used to show the actual scatter for the different species.

The point O represents the point of birth for the animal species.

The points C and B represent the time of conception and the time

of birth for man. The difference between these two curves in

childhood and adolescence (up to 14 years of age in man)

will be seen to be quite fundamental.

Figure 22. Scattergram showing the relative

growth rates to maturity for man and ten other animals. Re-drawn

after Brody (Science, September, 1944, page 207).

Figure 22. Scattergram showing the relative

growth rates to maturity for man and ten other animals. Re-drawn

after Brody (Science, September, 1944, page 207).

pg.6

of 39 pg.6

of 39

This

fact has been recognized for many years, of course, but many

textbooks are strongly biased toward human evolution and they

tend to omit information of this sort, because it requires explaining

and evolution has not come up with an explanation. But commenting

on the form of such curves, Bertalanffy had this to say: (177)

The time curve of growth in

mammals, fish, crustaceans, clams, and other classes follows

a pattern which is characterized by the fact that it approaches

a final weight by way of an S-curve. These characteristic growth

curves as well as different ones found in different groups such

as insects and snails, can be explained and predicted by a theory

of "growth types and metabolic types."

Since its pattern is essentially

the same, the growth of different species, such as a fish, a

mouse, an elephant, or man can be represented by the same curve

shape. Only the scales of unit of time and size are different.

In such comparison, only one organism,

man, makes an exception. In its first part, the human growth

curve is distinguishable from that of all other animals in that

a growth cycle seems to be added so that the infant period is

greatly prolonged, and the steep almost exponential increase

in size as is characteristic for early post-embryonic growth

curve may appear to be an insignificant detail but it has tremendous

consequences.

Thus animals run swiftly through

the period of the somatic and behavioural growth, and sexual

maturity is soon reached. In contradistinction the characteristic

shape of his growth curve gives man his uniquely long period

of growth and opportunity of a long period for learning and mental

development. It is an indispensable prerequisite of human culture.

Not only does

the human organism mature more slowly, but by comparison with

the bodies of other animals like him, it does not mature at

all in some respects, or only very late in life. For some

reason, the human body retains its youthful stages into adult

life. This is known technically as paedomorphism, and Sir Gavin

de Beer wrote at some length on the phenomenon in man. In his

Embryos and Ancestors, (178) he gave a chart showing for example, how the relationship

between the head, neck, and spinal column has retained in man

the configuration which it has in the embryo. In animals, the

head section swings through ninety degrees in order to bring

it into the right position for an animal which is to carry its

body horizontally. As we have seen, the position of man's head

and neck with respect to the organs of speech is very important,

making it possible for him to communicate while maintaining a

natural position. Thus, even in this respect, the changes which

take place in the maturing of animals carries them away from

the likelihood of acquiring the same capabilities that man has

as an adult. The whole design and structure

177. Bertalanffy, Ludwig von, "A Biologist

Looks at Human Nature", Scientific Monthly, January,

1956, p.36.

178. de Beer, Sir Gavin, Ancestors and Embryos, Clarendon

Press, Oxford, 1951, p.56.

pg.7

of 39 pg.7

of 39

and growth pattern of

man is of a piece, looking to the future potential, and in the

meantime involving him in a period of dependency through extended

immaturity, which results in the development of family relationships

which are not reflected in any other species.

Goldenweiser attaches great importance

from the cultural point of view to this protracted dependency

relationship in the life of the human infant: (179)

We know then that there is culture

and that it comes to man in the process of education. But even

this is not enough for an exact understanding of what it is that

happens here. One of the differences of what occurs in the case

of any animal on the one hand, and in that of man on the other,

is the rate at which they grow up.

With variations, as between animal

and animal, their young mature very fast. It is a matter of mere

months. So fast do they mature that were there much for them

to learn and had they the ability to do so, they could not, on

account of the very shortness of the period separating birth

from relative maturity. . . .

Fortunately for the animal, its

life is planned differently. It is equipped by nature with a

large assortment of instincts or reactive complexes which make

their appearance almost ready for action and which develop perfect

form after relatively few experiences. . . .

The factor in human life on the

other hand, which makes acquisition of vast knowledge and the

accumulation of experience possible for the young, is the so-called

prolonged infancy in man.

It is evident,

therefore, that man has not been provided with such instincts

as animals have for a very good reason. His pattern of behaviour

has been left "open" and not instinctive. This means

that he must learn for a longer period before he can become

independent, but it also means that he is free to a larger extent

in his behaviour and therefore responsible for it in a

way which animals never are. (180)

It is also important to underline

the significance of the fact that children of different ages

mature together. To my knowledge this never happens among animals

because the young are ejected from "home," not only

before the next brood is born but probably before the mother

becomes pregnant again. In some cases this is because she does

not come to heat until her family has left home, and in other

cases it is because the male is not allowed in the home while

the young are still dependent on the mother.

Now, the fact that we have a group

of children growing up at different stages of development is

of great importance in the

179. Goldenweiser, Alexander, Anthropology,

Crofts, New York, 1945, p.39.

180. For a discussion regarding moral responsibility of animals,

see Arthur Custance, "The Extent of the Flood," Part

I in The Flood: Local or Global? vol.9 of The Doorway

Papers Series.

pg.8 of 39

pg.8 of 39

formation of personality,

as Samuel Brody pointed out. The fact of diversity of age within

a single cohesive family has implications for the structure of

society. In the animal world there may be a number of offspring

growing up together but they will all be of the same age, and

for the most part they are likely to be the same size. The very

idea that any one of them might be responsible for the safety

or well-being of a younger sibling can never arise in this situation.

The whole idea of being responsible for one's fellows begins

to arise in a child's mind, not because it becomes aware that

the parents are responsible for it, but because it is made aware

of its own responsibility for others. Edward Sapir underscored

the significance of the "family" situation for the

development of social organization as a whole. He rejected an

older view that the organization of the family evolved out of

the kind of promiscuous clan structure in which, at first, everybody

made their own way with no special attachments or responsibilities:

(18l)

A more careful study of the

facts seems to indicate that the family is a well nigh universal

social unit, that it is the nuclear type of social organization

par excellence. So far from a study of clans, gentes,

and other types of enlarged kinship groups giving us the clue

to the genesis of the family, the exact opposite is true.

In case the

point should be missed and in view of its importance, it is worth

underscoring. Since family life in the human sense cannot be

derived directly from anything in the animal world, it was at

one time felt necessary to account for it through an intermediary

stage. Herds of protomen became herds of men with perhaps a herd

leader but no breakdown into small family units which were in

any way recognized or protected as such by the group. Such recognition

and such protection was then supposed to have emerged later.

A study of primitive people suggests that this is entirely unrealistic.

Moreover, there is some evidence that family life is as old as

fossil man. The finds at Choukoutien (China) and at Es Skhul

(Palestine) both seem to imply the same kind of family life.

Several adult males were involved in a single setting, and at

least in the case of the former, all were killed at the same

time -- men, women, and children.

Jacobs and Stern wrote: (182)

The absence of a stable

family unit has been claimed for early Pleistocene eras, but

no convincing arguments. . . have been adduced. All of the economically

most primitive societies known are characterized by monogamous

families, with rare but permissible polygamy or polyandry.

181. Sapir, Edward: quoted in Selected

Writings of Edward Sapir, edited by David C. Mandelbaum,

University of California Press, 1949, p.336.

182. Jacobs, M. and B. J. Stern, Outline of Anthropology,

Barnes and Noble, New York, 1947, pp.151, 152.

pg.9

of 39 pg.9

of 39

The lower

the technological level, the greater need there appears to have

been for a family of two persons, one a man who had relative

freedom of movement, the other a woman who did not have to hunt

or fish and who could therefore bare and nurse her baby.

It follows that the monogamous

family thus existed from the very beginning of culture �

that is to say, from eolithic or earliest paleolithic times.

. . The monogamous family and not promiscuity was, then,

in all likelihood the earliest form of family, and it has remained

the dominant form in all societies.

Goldenweiser

was even more specific and added that there is no evidence whatever

for any concept of communal ownership of any kind of property

at all, whether things or persons. He said, "The patent

facts do not at all support the a priori conception which

must be regarded as one of the ad hoc concoctions of the

evolutionists, who were looking for something less specific than

individual property . . . and found this in communal ownership."

(183)

Another factor which indicates

that family life in the sense of broad interdependence between

parents and children is unique to man, is the fact that fertility

in the human female tends to decline or cease at such an age

in her life span that she is not likely to have children so late

in life that she cannot perform the role of mother until the

child has reached an adequate stage of independence � more

particularly perhaps where female children are involved. Parents

will therefore live long enough under normal circumstances to

raise all the children to maturity. (184) Since the process of maturing in animals is so much

faster, fertility can be extended later in life. I believe this

is generally found to be the case. For example, C. R. Carpenter

mentioned a case of a female gorilla in a state of advanced senility

which was found to be carrying an infant when shot. (185)

In the animal world, the raising

of a brood cannot be compared with the raising of a family in

the world of man. Normally, in the latter, both man and woman

play a role of equal importance in terms of discipline, protection,

feeding, and education. In the animal world the role of the male

is entirely different in those species that might be supposed

to serve as prototypes for man. Among birds, both sexes will

care for the young, but this is something of an exceptional circumstance.

Certainly such a shared responsibility is not reflected among

the primates, and cannot possibly be the basis of human behaviour.

183. Goldenweiser, Alexander, Anthropology,

Crofts, New York, 1945, p.147.

184. Swartout, Herbert O., "The Meaning of the Origin and

Activities of the Human Body: Control of Growth and Aging in

the Human Body," Bulletin of Creation, the Deluge, and

Related Science, vol.4, no.5, 1944, p.71 f.

185. Carpenter, C. R., "Life in the Trees: The Behavior

and Social Relations of Man's Closest Kin," in A Reader

in General Anthropology, C. S. Coon, Holt, New York, 1948,

p.21.

pg.10

of 39 pg.10

of 39

The Role of the Male in the

Human Family

I cannot do

better than quote Ralph Linton on the role of the male in the

human family: (186)

There is no point at which present

day man departs more widely from the general primate condition

than in the male's assumption of responsibility for and care

of his offspring. Even the anthropoids seem to leave the care

of the young almost entirely to the females, although the males

may exhibit good-natured curiosity or even play with them.

Other authorities

would go further than this and say that in the great majority

of animal societies the male is actually antisocial. In some

instances this is so marked that the females take steps to incapacitate

the males in one way or another. In termite societies and other

such insect communities, the males are "sterilized,"

only just enough "unsterilized" males being left to

guarantee the continuance of the breeding process. Even among

domesticated animals where males and females are kept together

unnaturally, it is a common enough observation that one can easily

create a herd of cows, but a herd of bulls would be unthinkable.

The only way in which males can be added successfully to the

herd is by castrating them.

The primates reflect the same pattern

of rivalry, the old or stronger male builds his harem and drives

the other males to the periphery. This is particularly true in

the breeding season for the species. Once this season is over,

the males are apt to be excluded even from their own harem and

either form bachelor societies or become loners.

William M. Wheeler of Harvard,

in a paper entitled "Animal Societies," written years

ago, remarked: (187)

Owing to the decidedly unsocial

character of behaviour (of the male) which manifests itself almost

exclusively in voracity, pairing, or fighting with other males,

he is always so to speak socially more or less indigestible.

There seems to be no reliable record, at least among the lower

animals, of a male providing food for the female or the young,

or even protecting them.

Indeed, after pairing, the sexes

seem to become indifferent or even hostile to each other, and

the female retires to bear, suckle and rear her young in a safe

lair or retreat which she alone establishes. She thus forms a

family with her young of both sexes, and in advanced life may

become the leader of a herd consisting of several such female-offspring

families (this is true of ruminants, elephants, cetaceans, etc.).

. . .

The unsocial character of the male

reveals itself even more clearly, both among the lower mammals

and the anthropoid apes, when he becomes

186. Linton, Ralph, The Study of Man,

Appleton-Century, New York, 1936, p.148.

187. Wheeler, William M., "Animal Societies" in Biology

and Society section, Scientific Monthly, October 1934,

p.295.

pg.11 of 39

pg.11 of 39

senescent and impotent and wanders away

from the herd or troop, to lead the life of a rogue.

It was at one

time customary to view primitive cultures as representative of

a stage of social organization halfway between the anthropoids

and modern man. But it was very quickly apparent that the argument

did not hold, for among primitive people family relationships

are far more carefully hedged about and precisely defined than

in our own more advanced (?) society. And as far as the role

of the male is concerned, so much importance is attached to providing

every child with a father who is recognized as such that even

where the actual physical father has not been established, some

official father must be provided. Moreover, in some societies

where, until comparatively recent times, the role of the father

in procreation or the fact of "physical paternity,"

to give it its proper anthropological name, was not even recognized

(which was the case among the Trobrianders and some Australian

aborigine tribes, for example), even here a father had to be

apportioned, as it were, to each child. (188) Manifestly, therefore, in human social organization,

the role of the father was not established on a biological foundation.

It seems to be based on something more profound. It could be

that it goes back to Adam and God's appointment, in order to

provide a paradigm for our relationship to God Himself.

Complexification of Social Relations

Social organization

and Culture are quite distinct concepts. Culture is learned,

rather than instinctual behaviour, but social organization may

be entirely instinctual, as it is with insects. Kroeber observed,

"The presence of cultureless societies among insects is

an aid in distinguishing the two concepts in the abstract."

(189) It is estimated

that there are some 10,000 insect societies in which the organization

is highly complex. (190)

Referring to the behaviour of ants, Ruth Benedict observed: (19l)

The queen ant, removed to a

solitary nest, will reproduce each trait of sex behaviour and

each detail of the nest. The social insects represent nature

in a mood when she was taking no chances. The pattern of the

entire social structure Nature has committed to the ant's instinctive

behavior. There is no greater chance that the social classes

of an ant society or its patterns of

188. Physical paternity: see Arthur Custance,

"Light From Other Forms of Cultural Behaviour on Some Incidents

in Scripture,'' Part VII in Genesis and Early Man, vol.2

of The Doorway Papers Series

189. Kroeber, A. L., Anthropology, Harcourt & Brace,

New York, 1948, p.34.

190. Wheeler, William M., "Animal Societies" in Biology

and Society section, Scientific Monthly, October 1934,

p.291.

191. Benedict, Ruth, Patterns of Culture, Houghton Mifflin,

Boston, 1958, p.12.

pg.12

of 39 pg.12

of 39

agriculture, will be lost by an ant's

isolation from its group, than that the ant will fail to reproduce

the shape of its antennae, or the shape of its abdomen.

For better or for worse, man's

solution lies at the opposite pole. Not one item of his tribal

organization, or his language, or his local religion, is carried

in his germ cells.

Under human

influence, animals can be taught different patterns of behaviour,

but, as Schneirla pointed out, the learning process is stereotyped

and rote in character, limited to the individual and the given

situation. Unlike human societies where knowledge is cumulative,

"such special learning of each society (of animals) dies

with it." (192)

The important point here is that human learning processes are

cumulative and transferable, that is to say, they are not necessarily

tied to the situation in which the learning occurs, but can be

broadly applied. The experiments of Z. Y. Kuo with cats and rats

illustrates that learning dies with the individual. (193) He showed that cats could

be trained to play with rats rather than to kill them, but he

also showed that cats could be conditioned to be afraid of rats.

But the kittens of these cats so differently conditioned, when

raised in isolation, all became rat killers when they grew up.

Lorenz pointed out: (194)

In animals, individually acquired

experience is sometimes transmitted by teaching and learning,

from older to younger individuals, though such true tradition

is only seen in those forms whose high capacity for learning

is combined with a higher development of social life. True tradition

has been demonstrated in jackdaws, Graylag geese, and rats.

But knowledge thus transmitted

is limited to very simple things, such as path finding, recognition

of certain foods, and of enemies of the species, and in rats

knowledge of the danger of poisons. However, no means of communication,

no learned rituals, are ever handed down by tradition in animals.

In other words, animals have no Culture.

The matter of

path finding as learned behaviour is difficult to assess because

a number of social animals leave a trail of scent. The animal

which picks up this scent is not really following the trail by

imitation and learning is not strictly involved. This has been

demonstrated for many animals and insects. With respect to rats,

the situation is rather exceptional because it has been found

that when a colony of rats come across a new food, only one of

the rats will eat it while the others look on. The rest of the

rats will not touch the new

192. Schneirla, T. C., "Problems in the

Biopsychology of Social Organization," Journal of Abnormal

and Social Psychology, vol.41, 1946, p.385-402.

193. Kuo, Z. Y., "The Genesis of the Cat's Responses to

the Rat," Journal of Comparative Psychology, vol.11,

1930, p.1-30.

194. Lorenz, Konrad, On Aggression, translated by Marjorie

Kerr Wilson, Bantam Books, New York, 1967, p.64f.

pg.13

of 39 pg.13

of 39

food for two or three

days but will observe its effect on the single rat who has eaten

it. (195) Since

rats are rather unique in that they inhabit areas only where

man is and therefore are introduced to new foods provided by

man, their behaviour is in some sense unnatural and cannot be

taken as an example of what occurs in Nature among other species.

In man, culture and social organization

seem to go hand in hand, and both are learned: even in family

organization in so far as the roles of mother and father are

concerned, the behaviour patterns normal to a society are learned.

The roles may be reversed (as in the Tchambuli), combined or blurred (where all are alike, mother

and father, as among the Mundugumor or the Arapesh), or even

ignored entirely (as among the Alorese). (196) What we suppose to be the instinctive and therefore

predetermined role of the mother as opposed to the father is

evidently not instinctive, in spite of general impressions to

the contrary. It may be entirely absent; even mother love may

be lacking. (197)

Under circumstances which occur not infrequently, a mother may

not love her newborn but reject it. Scripture asks the question,

"Can a woman forget her suckling child?" (Isaiah 49:15).

The answer is, Yes, she may, according to Scripture itself.

It is difficult to know exactly

what goes on in the mind of a natural mother, whose culture differs

radically from ours, but judging by the fact that in a time of

famine such people will eat their newborn babies apparently without

hesitation, seems to indicate the absence of the kind of attachment

between mother and child which we assume to be instinctive. Such

behaviour has been reported from a number of primitive cultures.

Daisy Bates mentioned it several times in her study of the Australian

aborigines. (198)

One of the most difficult factors

about human culture is to understand why man insists upon elaborating

it to the point where it is not only no longer useful, but often

positively dangerous, as Susanne Langer observed: (199)

To contemplate the unbelievable

folly of which (men) the symbol-using animals are capable, is

very disgusting or very amusing, according to our

195. Garcia, John, "The Faddy Rat and

Us," New Scientist and Science Journal, February

7, 1971, p.254.

196. Reversed roles: Margaret Mead, Sex and Temperament in

Three Societies, William Morrow, New York, 1963; and Cora

DuBois, The People of Alor, University of Minnesota Press,

1944.

197. Mother love: see Robert Briffault, "The Origin of Love,"

in The Making of Man, edited by V. F. Calverton, Modern

Library, Random House, New York, 1931, p.497.

198. Bates, Daisy, The Passing of the Aborigine, Murray,

London, 1966: first published in 1938.

199. Langer, Susanne, Philosophy in a New Key, Mentor

Books, New York, 1942, p.27.

pg.14 of 39

pg.14 of 39

mood: but philosophically it is, above

all, confounding. How can an instrument develop in the interests

of better practice, and survive, if it harbors so many dangers

for the creature possessed of it?

Linton wrote

at some length about this anomaly, admitting that the reason

why men have gone on amplifying culture generation after generation

is still an unsolved problem: (200)

If Culture, like the social

heredity of animals, were simply a means of insuring survival

for the species, its progressive enrichment might be expected

to slow down and ultimately cease. . . Every society has

developed techniques for meeting all the problems with which

it was confronted passably well, but it has not gone on from

there to the development of better and better techniques along

all lines. Instead, each society has been content to allow certain

phases of its culture to remain at what we might call the necessity

level while it has developed others far beyond this point. .

.

Even in the case of tools and utensils

where the disadvantages of such a course would seem most obvious,

we have plenty of examples of quite unnecessary expenditure of

labor and materials. Hundreds of tribes ground and polished their

stone axes completely, although such instruments cut no better

than those ground at the bit and are actually more difficult

to haft. . . .

In rare cases the elaboration of

certain phases of Culture is even carried to the point where

it becomes activity injurious and endangers the existence of

the society. Many Eskimo tribes prohibit the hunting of seals

in summer. Although this meant little under ordinary circumstances,

there were times when it was highly injurious. It is said that

if land game failed, a tribe would often starve when there were

plenty of seals in sight. . . .

The natives of Australia in some

parts of that continent appear to be obsessed with social organization

and prohibit marriage between many different classes of relations.

It is said that in one tribe these regulations were worked out

to the point where no one in the tribe could properly marry anyone

else. . . This tendency towards unnecessary and in some cases

injurious elaboration of culture is one of the most significant

phenomena of human life.

It requires

little imagination to see this happening in our own culture with

grave consequences not only to ourselves but to mankind. The

future looks gloomy indeed. It would almost seem that man has

now organized and elaborated his culture for the elimination

of himself.

John H. Hallowell rightly observed

that with man, "economic desires are never merely the expression

of the hunger or the survival impulse in human life." (201) The lion's desire for

food is satisfied when his stomach is full. Man's desire for

food is more easily limited, but the hunger impulse is subject

to the endless refinements and perversions of the gourmet. Shelter

and raiment serve entirely other purposes,

200. Linton, Ralph, The Study of Man,

Appleton-Century, New York, 1936, pp. 87-90.

201. Hallowell, John H., Religious Perspectives in Political

Science, Religious Perspectives in College Teaching, The

Edward Hazen Foundation, New Haven, Connecticut, no date, pp.17,18.

pg.15

of 39 pg.15

of 39

man's coat never being

merely a cloak for his nakedness, but the badge of his calling,

the expression of an artistic impulse, a method of attracting

the opposite sex, or a proof of a social position His house is

not merely his shelter, but becomes an expression of his personality

and the symbol of his power, position, and prestige.

It is a curious thing that this

drive towards complexification seems to be almost a drive toward

suicide. Individually, very few primitive people commit suicide,

and as a rule they tend to do so only when old age has brought

their powers of contributing as expected to their society to

an unacceptably low level. In such cases suicide becomes part

of the cultural pattern and is not frowned upon. By adopting

this "out," they are actually redeeming themselves.

But in our complex civilization suicide does not have any socially

redeeming features about it; it is only an acknowledgment of

despair and total failure. The primitive may seek and receive

the help of his own fellows to end his life in a culturally acceptable

way. (202) With

us, such behaviour is totally unacceptable. Nevertheless, every

year the suicide rate goes higher and higher as our civilization

becomes more complex, a circumstance which suggests that the

complexification of culture may have something inherently inimical

to man about it. We suppose that culture evolved by the same

kind of natural process as everything else that is assumed to

have evolved from the simple to the complex. But no animal society

ever deliberately elaborates its organization to the point where

it endangers the species. It should not be supposed that primitive

societies are incapable of such complexification. This is obviously

not the case, as Linton pointed out with the Australian aborigines,

whose culture is otherwise the simplest known to us in modern

times. Moreover, research has shown that primitive languages

consistently turn out to be more complex than modern languages,

when they are adequately studied. So somewhere there is in man

a tendency which has become entirely harmful to him and in fact

may very well endanger his existence as a species. Other animal

species have disappeared when their environment changed or as

a consequence of the predatory habits of man, but no other species

has deliberately followed a course of increasingly complicating

its patterns of behaviour to its own increasing detriment. Arthur

Koestler attributed this to a fault in the mechanism of man's

mind, a mechanism which he considered to be faulty not because

it is too limited, but because its potential is altogether too

great for man to control himself. He would not have

202. See, for example, the Yahgans as reported

by Thomas Bridges in C. S. Coon, The Story of Man, New

York. Knopf, 1962, p.97 [unable to verify � Ed.].

pg.16

of 39 pg.16

of 39

suggested such a thing,

but to me this looks like clear evidence of the Fall, sin, which

has disrupted human nature in its every aspect � physiologically,

spiritually, and intellectually. Koestler wrote: (203)

When we say that mental evolution

is a specific characteristic of man and absent in animals, we

confuse the issue. The learning potential of animals is automatically

limited by the fact that they make full use � or nearly full

use -- of all the organs of their native equipment, including

their brains.

The capabilities of the computer

inside the reptilian and mammalian skull are exploited to the

full, and leave no scope for further learning. But the evolution

of man's brain has so wildly overshot man's immediate needs that

he is still breathlessly catching up with its unexploited, unexplored,

possibilities.

It is well known

that neurologists estimate that even at the present stage we

are using only 2 or 3 percent of the potentialities of the brain's

built-in "circuits." (204)

It seems as though man is operating,

therefore, at an exceedingly low efficiency in terms of his potential.

Either he was made this way which would be a solecism in Nature,

or he is a fallen creature. In either case, since animals were

not made this way, operating as they do probably at near 100

percent mental efficiency relative to their capacity, man is

in a class by himself. Presumably if he had not fallen, he could

safely have complexified his culture perhaps to fifty times what

it is without the slightest ill effects ensuing.

continued. . . . .

203. Koestler, Arthur, The Ghost in the

Machine, Hutchinson, London, 1967, p.299.

204. Koestler, Arthur, The Sleepwalkers, Hutchinson, London,

1959, p.514.

pg.17a of 39

pg.17a of 39  Copyright © 1988 Evelyn White. All rights

reserved

Previous Chapter Next

Chapter

Copyright © 1988 Evelyn White. All rights

reserved

Previous Chapter Next

Chapter

Home | Biography

| The Books | Search

| Order Books | Contact

Us

|