|

Abstract

Table of Contents

Part I

Part II

Part III

Part IV

Part V

Part VI

Part VII

Part VIII

Part IX

|

Part II: The Nature of the Forbidden

Fruit

Chapter 2

The Testimony of Tradition

A FEW CENTURIES

ago, tradition concerning early human events was believed without

question. But about seventy-five years ago a complete swing of

the pendulum had occurred. And just when traditions were being

gathered and collected most usefully from many previously unknown

sources. it became the fashion to consider them as interesting,

but quite untrue. However, as archaeology came into its own,

one confirmation after another of often the most unlikely details

came to light, and today secular traditions are treated with

a great deal more respect.

Yet after all is said and done,

one cannot really prove anything by an appeal to such a source.

But where it is found that traditions which refer back to some

common event present a concordant testimony in terms which are

slightly discordant, their testimony is of some significance.

It is generally agreed in a court of law that where several independent

witnesses agree too closely in their testimony, one should suspect

collusion and question the value of their statements. In those

ancient traditions which refer back to the Fall of man there

is just that measure of agreement and disagreement that has the

ring of truth.

For example, sometimes the forbidden

fruit comes from a good tree and sometimes from a bad tree; at

times the consequences were just great enlightenment and at others

great darkness. In some instances the being who tempts man is

good and in others evil. Most of these contradictions can be

resolved simply enough when we have the true account which is

presented in Scripture as a guide. The tree was both good and

evil, the consequences were both gain and loss. But it is not

unnatural for people to suppose that a being who introduced man

to an advanced kind of knowledge must be good. And the judgment

itself, in so far as death was introduced, was in a way a blessing

in disguise.

pg

1 of 9 pg

1 of 9

To

illustrate this last point: in a book entitled The Origin

of Death According to African Mythology, the author, Hans

Abrahamson, has given a pretty exhaustive account of the subject.

(16) He began with

the most widespread and prevalent African myths of death, originating

through a perverted message, some act of negligence or unwise

choice on the part of men, or through opening a fatal bundle

in which death resided. A divine ordeal is then illustrated and

discussed. This leads to a consideration of "discord"

in the first family, under four subheadings, and then to myths

of death caused by human beings engaging in sexual intercourse,

regarded as a practice forbidden by the Creator. According to

the author the notion of death sometimes shows traces of the

influence of the Eden story, but the traditions are couched in

such terms that he felt they have not originated from Christian

or Jewish sources.

Rather unusual, in Abrahamson's

opinion, is the contention that death is good and is desired

by man as an expression of life weariness resulting from his

wickedness. In most of the traditions the initiative is taken

by the High God or by some other Divine Being who permits death

to enter the world.

In India, one primitive group have

a tradition of the Fall which contains certain details that bring

us a little closer to the clue we are seeking. S. H. Kellogg,

who believed that these people did not borrow their story from

Christian sources, gave the following account: (17)

The Santals have a tradition

. . . that in the beginning they were not worshippers of demons

as they are now. They say that, very long ago, their first parents

were created by the living God; and that they worshipped and

served Him at first: and that they were seduced from their allegiance

by an evil spirit, Masang Buru, who persuaded them to drink an

intoxicating liquor made from the fruit of a certain tree.

S. L. Caiger,

in a most useful little handbook of archaeology and the Bible,

gave a translation of a small fragment of a cuneiform tablet

which professes to identify the tree: (18)

My King the cassia plant approached;

He plucked, he ate.

Then Ninharsag in the name of Enki

Uttered a curse:

"The Face of Life, until he dies,

Shall he not see."

16. Abrahamson, Hans, "The Origin of

Death: Studies in African Mythology," reviewed in Man,

September, 1952, p.137.

17. Kellogg, S. H., Genesis and the Growth of Religion,

Macmillan, New York, 1892, pp.60, 61.

18. Caiger, S. L., Bible and Spade, Oxford University

Press, 1936, p.19.

pg.2

of 9 pg.2

of 9

For

the reader unfamiliar with early Mesopotamian mythology, Ninharsag

and Enki were deities. This little fragment for all its polytheistic

colouring nevertheless has preserved one element of the story.

Man could not come face to face with God again except by passing

through death. The term "the face of life" probably

means "the face of Him who is the source of life" (cf.

Exodus 33:20; John 14:6).

The same author gives another version

of the Eden story from a tablet which indicates a condition of

perfect harmony in nature prior to the Fall. The biblical Adam

is represented by one whose name is given as Enki, whom we have

seen in the previous tablet as a deity. It was quite customary

to deify important figures, and as a matter of interest the name

is probably composed of two words En and Ki meaning Heaven and

Earth -- appropriate enough in view of the fact that Adam stood

as a link between heaven and earth. The tablet runs as follows:

(19)

In Dilmun, the Garden of the gods,

Where Enki and his consort lay,

That place was pure, that place was clean,

The lion slew not, the wolf plundered not the lambs,

The dog harried not the kids in repose,

The birds forsook not their young,

The doves were not put to flight.

There was no disease or pain. . . .

This picture

remarkably parallels that vision which Isaiah had of the future

when the Lord should return to reign in righteousness (Isaiah

11:69; 65:25).

W. St. Chad Boscawen gives another version

which has been found on a cuneiform fragment as follows: (20)

The great gods, all of them determiners of Fate,

Entered, and death-like, the god Sar filled.

In sin, one with the other in compact joins.

The command was established in the Garden of the god.

The asnan fruit they ate, they broke in two:

Its stalk they destroyed

The sweet juice which injures the body.

Great is their sin. . . .

Like many other

such cuneiform texts the meaning is not altogether clear. Not

only are some of these fragments in rather mutilated condition

but the translation of cuneiform itself still presents

19. Ibid.

20. Boscawen, W. St. Chad, The Bible and the Monuments,

Eyre and Spottiswoode, London, 1896, p.89.

pg.3

of 9 pg.3

of 9

some problems. It is

interesting to find, however, in what is evidently a very early

tradition, that it was the juice of a fruit which injured the

bodies of "Adam" and his consort. This, of course,

makes the assumption, which may or may not be justified, that

this tablet is a recollection of the events in Eden.

One of the most complete of these

early stories is known as the Adapa Myth. It is not necessary

to detail it here, for much of it does not have to do with that

particular aspect of the Fall with which we are concerned. However,

George Barton has given a translation of some of the sections

that are not mutilated, which seem clearly to reflect the Eden

story. In the third tablet, referring evidently to the action

of one of the gods, on line 16 we find the words, "The sickness

which he placed in the bodies of the people." (21) This is followed in line

19 by the words, "Destruction shall fall upon him."

This again is not as clear in meaning as one would wish, but

we might be justified perhaps in viewing this as a reference

to the Tempter upon whom judgment was pronounced after he had

robbed man of his original perfect health. One thing which may

be noted about all these fragments is that they all seem to have

in view a real fruit containing a real poison which had very

real material consequences. It is not, I think, because the writers

did not have a sense of spiritual values that they laid so much

emphasis upon the physical effects of the Fall. The sense of

sin in cuneiform literature is well marked and some of the penitential

psalms are remarkable for the real sense of unworthiness that

they reveal. It seems that the emphasis in these traditions must

rather be the result of a conviction that the Fall of man in

the form in which we find it most completely stated in Genesis

was sober history. In these traditions at least, there is not

merely allegory. This is history -- though distorted.

By now the reader will probably

have begun to surmise something of the nature of the forbidden

fruit. The Santal tradition says it contained an intoxicating

liquor. Another fragment speaks of it as having a certain sweetness

but being injurious to the body. In a paper first published in

the Transactions of the Victoria Institute some time ago, T.

G. Pinches told his audience of the finding of a cuneiform tablet

which opens thus: (22)

In Eridu grew a dark vine,

In a glorious place it was brought forth.

21. Barton, George A., Archaeology and

the Bible, American Sunday School Union, Philadelphia, 1933,

p.322.

22. Pinches, T. G., "On Certain Inscriptions and Records

Referring to Babylonia and Elam," Transactions of the

Victoria Institute, vol. 29, 1895, p.44.

pg.4

of 9 pg.4

of 9

The

phrase "a dark vine" might be rendered a "vine

of darkness." Although there is a sense in which it brought

light, there is a more terrible sense in which it brought Adam

and Eve into darkness. The "glorious place" is presumably

Eden. Some years ago the Rev T. Powell read a paper before the

same Institute in England which was entitled, "A Samoan

Tradition of Creation and the Deluge." (23) In this story the vine again figures prominently.

It is said that the gods planted it expecting it to turn out

to bear a beautiful fruit -- but it bore worms. Out of these

worms, so the tradition says, four human beings were finally

created, who settled local areas within the vicinity of Samoa.

From a cylinder seal we have an

impression by some Babylonian artist of what the scene in Eden

was like. These seals were used like a miniature rolling pin

to make an impression on a blob of clay which then identified

the sealed package as belonging to a certain individual known

by his particular seal. We have given an illustration of it here

which, however, does not show too clearly the detail of the original.

Actually it is a man and a woman seated on either side of a tree

whose leafy branches run straight out on either side in a very

formal pattern. Two clusters of fruit hang down near the base

of the trunk. Behind the man is a representation of a serpent.

Both figures reach forward to pluck the fruit.

Fig. 6 � The Seal of Adam and Eve amd the Serpent

as shown in a wodcut appearing in Smith's "Chaldean Account

of Genesis."

23. Powell, T., "On the Samoan Tradition

of Creation and the Deluge," Transactions of the Victoria

Institute, vol.20, 1886, p.154, 155.

pg.5

of 9 pg.5

of 9

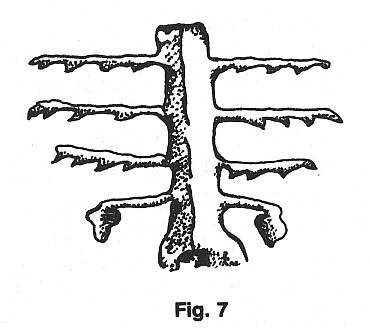

From

another photograph of the same seal impression we have redrawn

the tree itself so as to show more clearly the actual shape of

the fruit. Although our interpretation of what may be intended

may not, of course, be correct, it would certainly require no

great stretch of the imagination to suppose that the artist was

trying to show two clusters of something like grapes hanging

down.

The formal arrangement

of the branches may be merely an artistic device, but it could

also be the result of observing the branches of a vine which

had been trained along some artificial support.

The Book of Enoch has always had

a special interest for Christians in view of the fact that it

is the only non-canonical book quoted in the New Testament and

is not bound with the Bible even when the Apocrypha are included.

The allusions to it are not infrequent, and it is generally held

that the title "the Son of man" was taken from it.

In chapter 32 the writer of the book told how he went in search

of the Garden of Eden:

Finally I came into the Garden

of Righteousness, and saw a many coloured crowd of trees of every

kind, for many and great flourished there, very noble and lovely;

and the tree of wisdom which gives life to anyone who eats it.

It is like the Johannis bread tree: its fruit is like a cluster

of grapes, very good.

The writer of

the book then went on to tell how he questioned his angelic guide

about this particular tree:

I said, Fair is this tree and

how beautiful and ravishing its look, and the holy angel Raphael

who was with me answered and said to me, This is the tree of

wisdom of which thy forefathers, thy hoary first parent and thy

aged first mother, ate and found knowledge of wisdom: and their

eyes were opened and they knew that they were naked: and they

were driven out of the Garden.

Some years ago,

Francois Lenormant mentioned the finding of a

pg.6

of 9 pg.6

of 9

curiously painted vase

of Phoenician manufacture, probably of the 6th or 7th century

B.C. (24) This had been discovered in an ancient sepulcher in

Cyprus. It exhibits a leafy tree "from the branches of which

hang two large clusters of fruit," while a great serpent

advances with an undulating motion towards it.

The American Journal of Archaeology

some years ago carried an article by Nelson Glueck reporting

on the general findings in Palestine and elsewhere during the

years of excavation immediately prior to 1933. He mentioned:

(25)

In one of the two tombs discovered

southwest of the Jewish colony of Hedra, a lead coffin was found.

On one side it is decorated with an arch which rests upon two

twisted columns. Under the arch stands a naked boy who holds

a serpent in his right hand and a bunch of grapes in his left.

A coffin is

a particularly significant background for a picture of man in

his youth, naked, and holding in either hand the elements out

of which physical death may have found its way into human experience.

As a matter of fact, although commentaries rarely mention it,

it appears that some of the great Jewish rabbis understood that

"the Tree of Probation" was the vine.

Paul Isaac Hershon, in his book,

A Rabbinical Commentary on Genesis, stated that in Genesis

3:6, against the words "that the tree was good for food,"

there is this rabbinical comment: (26)

Some of the sages say that it

was a fig tree and that that was why they plucked the leaves

from the fig tree to cover their shame: for as soon as they had

eaten of the Tree of Knowledge their eyes were open, and they

were ashamed to go about naked.

But some sages say that the tree

was a vine. Eve pressed the grapes and gave Adam red wine to

drink, as red as blood.

A. Edersheim,

himself a Hebrew Christian, well versed in the lore of his own

ancient people, said that there were some rabbis who believed

that when Noah left the Ark to become a husbandman, he planted

a vineyard from a slip of a vine that had strayed out of Paradise.

(27)

At the beginning of this chapter,

we pointed out how traditions may become confused and details

transposed so that sometimes what was bad became good and what

was a source of death became a source of life. Thus the Tree

of Knowledge came in some cases to be

24. Lenormant, Francois, Contemporary Review,

September, 1879, p.155.

25. Glueck, Nelson, American Journal of Archaeology, January-March,

1933, p.164.

26. Hershon, Paul Isaac, A Rabbinical Commentary on Genesis,

Hodder and Stoughton, London, 1885, p.27.

27. Edersheim. A., The World Before the Flood, Religious

Tract Society, London, no date, p.55.

pg.7

of 9 pg.7

of 9

confused with the Tree

of Life, as was evident in the Book of Enoch where we are told

that the Tree of Wisdom (i.e., Knowledge) gave Life to all who

ate of it, although the rest of the story clearly indicates that

the writer is not actually referring to the Tree of Life. Now

that we have explored the view that the forbidden fruit was some

kind of fruit containing a juice which was potentially a poison,

there will surely be some who will say, "You don't really

think that the forbidden fruit was a grape?" To this we

must reply, first, that that view has the support of traditions;

secondly, that a fruit capable of producing alcohol in some form

supplies us with a poison that seems to fulfill all the conditions

set forth in chapter 1; thirdly, that with this as a clue, many

passages of Scripture take on a new significance and greatly

tend to confirm the interpretation; and fourthly, that it is

not absolutely necessary to argue for a grapevine so long as

it was a fruit from which could be derived a form of poison of

very similar nature that would act upon the body in a very similar

way. This last requisite may have been stated in a rather redundant

fashion, but it is in the nature of a specification. Some further

details of this specification will be given in due course.

With these interjected remarks

we may therefore proceed to consider certain traditions of a

slightly different kind. Lenormant told us in another place:

(28)

The most ancient name of Babylon

in the idiom of the first settlers in that region was "the

Place of the Tree of Life," and even on the coffins of enameled

clay of a date later than Alexander the Great, found at Warka

(the ancient Erek of the Bible, and the Uruk of the inscriptions)

this tree appears as the emblem of immortality. Strange to say,

one picture of it on an ancient Assyrian relic has been found

drawn with sufficient accuracy to enable us to recognize it as

the plant known as the Soma Tree by the Aryans of India, and

the Homa of the ancient Persians, the crushed branches of which

yield a draught offered as a libation to the gods as the water

of immortality.

It might be

argued that we have here much better evidence to support a theory

that it was the Tree of Life which was a vine rather than the

Tree of Knowledge -- for after all this is what the discovery

implies. When the tradition speaks of the Tree of Life, we probably

have really a reference to the Tree of Knowledge, the same confusion

having occurred as we have seen in the Book of Enoch. The Soma

or Homa Tree is generally considered to be the Asclepias acida,

a tree associated in the Vedic hymns with the god Soma. It was

important in Vedic ceremony, in the words of one encyclopedia,

"because of its

28. Lenormant, Francois, The Beginnings

of History, Scribners, New York, 1891, pp.85, 86.

pg.8

of 9 pg.8

of 9

alcoholic qualities.

. . ." In one hymn, those who have drunk the juice of the

plant are said to exclaim together, "We have drunk the Soma;

we have become immortal; we have entered the light; we have known

the gods!" All these assertions can be related to the assurances

given by Satan when he tempted Eve to take the forbidden fruit.

Moreover, there is a beautiful association of ideas in certain

biblical passages which seem to mark this vine for what it was

-- a false vine. The Lord Jesus said, "I am the true vine"

(John 15:1): the Psalmist said "Taste and see that the Lord

is good" (Psalm 34:8).

And this brings

us to a consideration of the many references in Scripture to

the grapevine, which reveal its influence in human history and

have rendered it the special object of both praise and blame.

After this we shall examine in what way it fulfills the exact

requirements of our theory from the points of view of genetics

and biology.

pg.9

of 9 pg.9

of 9  Copyright © 1988 Evelyn White. All rights

reserved

Previous Chapter Next

Chapter

Copyright © 1988 Evelyn White. All rights

reserved

Previous Chapter Next

Chapter

|