|

Abstract Table of Contents

Part I

Part II

Part III

Part IV

Part V

Part VI

Part VII

Part VIII

Part IX

| Part IV: The Virgin Birth and the Incarnation Chapter 1 The Virgin Birth WHEN CORRECTLY understood, the concept of physical immortality is quite familiar to research workers in the life sciences. It is, however, important to understand in what way the term "immortality" is used in such a context. It does not mean that an organism which is immortal cannot be put to death; it does mean that it need not die. Protected adequately against every circumstance which would endanger its life from without, living protoplasm is not intrinsically subject to natural death. There is a very general agreement today that physical death is in no sense an inevitable consequence of being alive, as H. J. Muller put it: (1) "Natural death is not the expression of an inherent principle of protoplasm."

The reason why anything that has once come alive should have natural limitations to prevent it from continuing alive endlessly is not precisely known. Certainly some forms of life do have such limitations. Yet, in terms of individuals, if by "individual" one means a self-contained living organism whether plant or animal and if the simplest as well as the more complex forms of life are included, i.e., unicellular as well as multi-cellular, then immortal creatures far exceed in numbers those creatures which in our present state of knowledge appear to be mortal by nature, and immortality proves to be a far more common phenomenon in Nature than mortality is. There are untold billions of living plants, trees, and other things which do not appear to have any limitations placed upon their continuance other than those which result from accident, and by accident I simply mean events fatal to the organism but not originating within itself. Precisely the same applies to even more billions of micro-organisms whose nature it is simply to divide, and divide, and 1. Muller, H. J., "Life," Science, vol.121, 1955. See also "If Adam Had Not Died", Part III in The Virgin Birth and the Incarnation, vol.5 of The Doorway Papers Series.  pg 1 of 17 pg 1 of 17

go on dividing, endlessly. They, too, leave no corpses unless they are actually killed. Even some larger organisms in the sea appear to be capable of living on indefinitely until they meet with some accident which terminates their existence. But since, when counting the actual number of living things in the world, size does not enter in the calculation per se, it is unquestionable that potentially immortal creatures far outnumber the mortal ones. The phenomenon of "natural" death, in spite of all appearances to the contrary, applies to the few, not to the many. Immortality far outweighs mortality in terms of numbers of individuals which enjoy it. Plants and simpler forms of free-living things such as paramecia, etc., need never die. The cells of which they are composed reach a certain size, divide, and continue as two daughter cells. Barring accidents, the process of division and multiplication goes on indefinitely. They leave no dead and the continuity of life is unbroken.

It is true that such cells may be destroyed by dehydration, shock, starvation, crushing, predation, disease, poisoning, heat, cold, and so forth, but if they are protected from accidents of this sort, death never becomes part of their experience. In short, as far as can be determined in the present state of knowledge, death is by no means the inevitable conclusion of life. Even in many higher forms this is true. Some naturalists believe that few, if any, animals die a natural death. (2) They are always "killed" in some way. Senescence or aging has the appearance of being characteristic of more complex forms of life, but the process may seem to be such only because the longer an animal lives the more likely it is to be exposed to the effects of wear and tear or to some fatal injury and the less able it is to sustain the repeated shocks of life. It is simply worn down. Yet the aging process itself is, paradoxically, found to be most rapid when the organism is youngest. (3) The organism ages (though no one knows precisely what aging means at present) more rapidly when it is young and experiences a slowing up of the process as the years go by. A curve drawn to relate the rate of aging with the passage of time starts with a high rate, falls rapidly at first, and then gradually levels off, theoretically never quite touching the base line. In short, the curve is described as asymptotic. In "old age" the aging process ceases almost entirely. However, what does happen is that the power to recover from shock or attack in any form decreases, until the organism has much less "survival" capacity or resilience, and is then more easily killed. Under ideal conditions and with full protection 2. Medawar, Sir Peter B., The Uniqueness of the Individual, Basic Books, New York, 1957.

3. Ibid., p.21.  pg.2 of 17 pg.2 of 17

from all such threats to its continuance, it is probable that it would go on living, if not indefinitely, at least for an enormous length of time.

Huxley speaks of trees in India that have been adequately protected as living on for centuries where, in Nature, they would only have survived a few score years. (4) Circumstances have occasionally favoured certain animals whose life span has similarly far exceeded that which is normal for the species. Cultures of animal tissue have been shown to be capable of resisting death for many, many times the normal life span found in Nature, as, for example, chicken tissue kept alive by Alexis Carrel for 27 years. (5)

In fact, it is now quite widely believed that there is no inherent reason why man might not at some time in the future live on for centuries, nor why he might not have lived on for centuries in the past before he had accumulated enough defective genes to reduce his chances of survival or actually to cause life to be shortened intrinsically. Indeed, and this is a point of fundamental importance, there is no reason why man may not originally have been created as an immortal creature from the physiological point of view, as I believe Genesis clearly implies.

This is not merely the wishful thinking of Christians who are convinced of the trustworthiness of the biblical record of man's creation. Physical death may never have been part of man's original makeup. (6) We know that in the present economy of things, men are destined to die (including even those who were translated like Enoch and Elijah), for Scripture clearly states that it is appointed unto men to die once. There are intimations that Enoch and Elijah will be returned to this scene of woe in the end time to suffer martyrdom for 4. Huxley, Sir Julian, "The Meaning of Death," in Essays in Popular Science, Penguin Books, Harmondsworth, 1938, p.105.

5. Sherrington, Sir Charles, Man on His Nature, Cambridge University Press, 1963, p.118.

6. The fact is that in spite of a great deal of research into the nature of death carried out over the past 25 years, the reasons why we die and even the definition of death itself are still very open questions. "Death from old age" is still a legal fiction as Edward Deevy put it ("The Probability of Death" in Scientific American, April, 1950, p.59). Sir Peter B. Medawar emphasizes the extreme difficulty of finding one single undeniable record of any individual dying a truly "natural" death (ref. 2, p.18). Dr. Hans Selye asserted that in all his autopsies he has never yet seen a man who died of old age, nor did he think anyone ever has. See Stephen E. Slocum, "Length of Life," Journal of the American Scientific Affiliation, vol,13, no. I, 1961, p.19.

Years ago August Weismann wrote: "We do not know why a cell must divide 10,000 or 100,000 times and then suddenly stop. It must be admitted that we can see no reason why the power of cell multiplication should not be unlimited, and why the organism should not therefore be endowed with everlasting life." See his Essays Upon Heredity and Kindred Biological Problems, translated by E. B. Poulton, S. Schonland, and A. E. Shipley, Oxford University Press, 1889, p.22, in an essay entitled "The Duration of Life." His remark is as fundamentally true today as it was then.  pg.3 of 17 pg.3 of 17

their testimony. (7) But Adam was not so constituted at first. As Augustine has so succinctly said, "It was not impossible for him to die, but it was possible for him not to do so." The first part of this observation is manifestly true, for after 900 years Adam did indeed die (Genesis 5:5): but the second part of the statement is equally true, for Genesis makes it clear that if Adam had been able to go back to the Tree of Life to eat of it or take of its leaves which were for healing (Revelation 22:2), this "medicine" would have counteracted the poison which had now entered into his body and would have restored to him once more his original state of immortality. The possibility of such an event consigning man to the fate of an unending life as a sinful creature was too terrible to contemplate, and God at once drove him out of the Garden in order to prevent it. For this very reason, the angel stood at the entrance to the Garden, sword in hand, to forestall access specifically to the Tree of Life (Genesis 3:24), the sword being a symbol of death. (8)

The broad picture presented here of an immortal Adam and Eve losing their immortality by partaking of the forbidden fruit has been widely reflected in both Jewish and Christian commentaries from the very earliest times. I think it is an indication of the power of Scripture that it provides clues in matters certainly not known at the time to the original writers which merely by contemplation of the text allowed early Jewish commentators to draw some conclusions that were, I believe, remarkably near the truth. Much of their comment is fanciful indeed, but now and then they achieved remarkable insights into matters which have remained obscure to natural science for thousands of years. In his Legends of the Jews, Louis Ginsberg (9) quoted from one of the Midrashim to the effect that celestial beings are not propagated but immortal, whereas earthly beings are propagated but are not immortal: "Whereupon God said, I will create man to be the union of the two, so that when he sins, when he behaves like a beast, death shall overtake him; but if he refrains from sin, he shall live forever." Subsequently, in a later volume, Ginsberg refers to the fact that according to Jewish tradition "at the creation of man it was God's intention that he be free from sin, immortal, and capable of supporting himself by 7. Revelation 11:3-12.

8. No man has access now to the Tree of Life which holds the secret of immortality except by first surrendering the life he now has.

9. Ginsberg, Louis, from the Midrash on The Great Beginning, Wilna edition, 1887, chap.7 pare11; chap.12, pare.8; chap. 14, pare. 3: quoted in Legends of the Jews, vol.1, Jewish Publication Society, Philadelphia, 10th impression, p.50.  pg.4 of 17 pg.4 of 17

the products of the soil without effort." (10) In Volume V, which contains the documentation of the four previous volumes, Ginsberg also notes that according to Zohar (Parasha I, Caption 60b to 61a) the opinion is expressed that Adam might have lived "a pure spiritual married life in paradise, and if he had not sinned would have begotten immortal children," as well as being himself immortal. (11)

In his edition of The Commentary of Nahmanides on Genesis 1-6, Jacob Newman (born 1195) translates the comment on Genesis 2:17 as follows: "In the opinion of our Rabbis, if Adam had not sinned he would never have died, for the superior soul gives life forever."(12)

Although the following is a digression, it bears directly upon a secondary aspect of Adam's physiological makeup as first created and relates to the subject matter of chapter 3 of this paper. According to Nahmanides, it was generally believed by the older Jewish commentators that Adam was created "with two faces." (13) Newman lists several Jewish sources supporting this view and in his own notes suggests that the meaning is that Adam was originally hermaphroditic, i.e., bisexual.

Usually the classical deity, Janus, was shown with two faces, both of them male, a circumstance traditionally explained as symbolizing the fact that the god of the New Year (after whom January is named) faced both ways and looked towards the old year and towards the new. But the Jewish interpretation of Adam as "two-faced" has a somewhat different significance, since it symbolized an individual who had the face of a man and the face of a woman, combining the two sexes in the one person. For some reason the Hebrew word for "face" is always written in a plural form. It is interesting to note that research into factors governing facial asymmetry reveals that almost all people have "two faces," a left face and a right face. Fritz Kahn, (14) speaking of the musculature in this area, notes the asymmetry here and observes: "The right face is generally harder, the left face softer and more feminine in character. For this reason in the majority of cases painters and photographers portray women from the left." I'm not sure how correct his conclusion is regarding portraiture, but the existence of two distinct faces has been well established by photographic techniques. In an article entitled 10. Ibid., vol.3, p.106.

11. Ibid., vol.5, p.134.

12. Newman, Jacob, The Commentary of Nahmanides on Gen. 1-6, Brill, London, 1960, p.71.

13. Ibid., p.72 and xx, fn.141.

14. Kahn, Fritz, Man in Structure and Function, vol.1, Knopf, New York, 1960, p.151.  pg.5 of 17 pg.5 of 17

"Wish Image and Fear Image," Werner Wolff, (15) Assistant Professor of Psychology at Bard College, presented some of the evidence derived from so-called bi-face photographs of children, animals, primitive people, Egyptian mummies, death masks of famous people, and transvestites (people who are of one sex but prefer to dress in the clothes of the opposite sex). It is with the last class that we are concerned here. The principle of bi-face photography involves taking a true frontal view of the face and then cutting the negative precisely down the center and printing two left sides (one mirrored) to make a complete left face, and similarly two right sides to make a complete right face. The extraordinary thing is that in the case of one male transvestite, when shown a bi-facial view of the right side (i.e., the masculine side of his own features), he failed to recognize himself and disliked what he saw. When shown a bi-face portrait of the left side, he not only recognized himself but liked the portrait and thought it represented a nice person. The two bi-face portraits are reproduced in Wolff's article along with a conventional portrait, and there is no doubt that the right side did produce an athletic and masculine portrait and the left side a gentle and feminine one. Photographs of transvestites who were females produced precisely the same reaction, only in these cases in reverse. It may be a far-fetched idea but it seems to me conceivable that the Jewish people had done some thinking about what kind of a face Adam would have to have if both sexes were combined in him until Eve was separated from him, and they may have come to the conclusion that he must really have had two faces in this sense. I do not think it an irreverent thought, but I suspect that when Jesus set His face like a flint, those who saw it, saw it as an all masculine face, whereas in His moments of overtly expressed compassion, His face must have been -- how else can one say it -- beautifully feminine. Man, physiologically speaking, has perhaps never quite lost the original image he once bore (a heavenly image where there is neither male nor female and therefore presumably both in one) and in greater or lesser degree still has a vestige of both faces depending upon his mood.

Returning, then, to the question of Adam's immortality as originally created. A number of the Church Fathers held that Adam was at first immortal. For example, Augustine argued that he was ''immortal by the benefit of his Creator," (16) by which he evidently intended that Adam could indeed have lived on forever, his body 15. Wolff, Werner, "Wish Image and Fear Image," in Ciba Symposium, vol,7, nos.1 and 2.

16. Augustine, De Generis, 1.25.36.  pg.6 of 17 pg.6 of 17

being so constituted that with the external aid of the Tree of Life he would have been continually renewed against any aging of his cells. In his commentary Questions on Genesis, Jerome proposed to adopt a translation for the conclusion of Genesis 2:17 that had been previously suggested by Symmachus: "thou shalt become mortal and liable to death," implying the same potential immortality to begin with. (17) The Roman Catholic view has been set forth in summary form by a Jesuit, Thomas B. Chetwood, in a work entitled God and Creation: (18) The immortality of Adam is explicitly defined by the Church. For the Sixteenth Council of Carthage (418 A.D.), the decrees of which were approved by Pope Zozimus, teaches: "If anyone shall say that Adam was created mortal, so that he would have died in the body whether he had sinned or not sinned, let him be anathema." And the same doctrine is confirmed by the decrees of Orange and Trent. Chetwood quoted Genesis 2:17, and with reference to the words "in the day that thou eatest thereof thou shalt surely die", he commented: (19) Unless Adam ate the forbidden fruit he would not be subject to death. He could not, clearly, be deprived, as a punishment, of something which he did not possess. The Fathers are unanimous in so understanding this passage and in their teaching of the original immortality of Adam and Eve. . . .

The human race lost the gift of immortality on account of Adam's sin. But Adam surrendered his potential immortality, it would appear, by eating a fruit which introduced into his body a protoplasmic poison. This substance began a process of dying in him that very day. From that moment he was doomed to mortality. Erich Sauer put it this way, (20) "At the moment of the sin, spiritual death entered and with it also, under the divine judgment, freedom from bodily death was forfeited. . . . Forthwith 'life' is merely a gradual dying, and birth is the beginning of death." It is not necessary to read the text of Genesis 2:17 as meaning that he actually died that very day, but that he did that very day lose his potential immortality. We have an interesting parallel in 1 Kings 2:36f. Solomon condemned Shimei to take up permanent residence in Jerusalem, where he was to be confined for the rest of his life. In Solomon's words (v. 37), "For it shall be, that, on the day thou goest out [of the city] . . . thou shalt 17. Jerome: quoted in Harold Browne, Commentary on Genesis, Scribners, Armstrong, New York, 1873, p.42.

18. Chetwood, Thomas B., S. J., God and Creation, Ben Zigger Brothers, New York, 1928, pp.145ff.

19. Ibid., p.146.

20. Sauer, Erich, The Dawn of World Redemption, Eerdmans, Grand Rapids, 1953, p.56.  pg.7 of 17 pg.7 of 17

know for certain that thou shalt surely die." We are told that Shimei stayed in Jerusalem according to the king's command for some three years, until certain of his servants ran away. Without stopping to think about the consequence, Shimei saddled his ass and went out after them. When he returned to the city and Solomon learned what he had done, he sent his official executioner and put him to death. The meaning of Solomon's warning is quite clear. Shimei was to understand that the day he disobeyed, from that time he was a doomed man.

In the strictest sense this newly acquired condition of mortality was passed on, as Romans 5:12 indicates, to Adam's descendants. We have here, therefore, one of those rare situations in which, to use the terminology employed in the life sciences, an acquired characteristic is inherited. This fact provides us with some clues about the fruit of the Tree of Knowledge, since there are only a few protoplasmic poisons the effects of which, once introduced into the bodies of the parents, may have the same effect upon the children, whether those children individually ingest the same poison or not. To understand how this comes about, it is necessary to enter briefly into a study of how the seed (ovum and spermatozoon) are formed and reproduce themselves.

Each new generation begins with the union of two seeds, one contributed by the man and one by the woman. The events which transpire in the preparation of these two seeds upon any one occasion of their being united is fairly well understood. When the male seed or spermatozoon finally reaches the seed of the woman, the ovum, it penetrates and fuses with it to form the first complete cell of a new individual organism. Shortly afterwards this first cell, which is called a zygote, divides into two cells, the total substance of which is equivalent to the original zygote. These two daughter cells, as they are called, themselves also divide, each into two cells, thus giving rise to a total of four cells. This process is repeated until there are 8 cells, and then 16 and 32, still without any total gain in substance. The cells are not all the same size but altogether their total mass has remained constant, so that the 32-cell body is still no larger than the original fertilized ovum. (21) This is known as the morula stage. It is believed that at this point a change takes place and by a process of differentiation a new type of cell arises by further division, and these new cells begin to build around the original morula a structure which is concerned with the provision of a vehicle or carrier for the original 21. Nelsen, Olin E., Comparative Embryology of the Vertebrates, Blakiston, Toronto, 1953, pp.114f.  pg.8 of 17 pg.8 of 17

germ cells, or "germ plasm," as Weismann termed it. This process of differentiation therefore marks the beginning of a new stage in the development of the individual. Whereas prior to this all the cells were duplicates of the original fertilized ovum, the new differentiated cells seem to lack the total capacity which the ovum has. (22) The original cells, which have come to be known as the germ plasm, are therefore distinct from the differentiated cells, which are termed the somatic or body cells. The somatic cells originate from the germ plasm; the germ plasm never originates from somatic cells. In the adult, the body which grows out of the differentiated cells forms a carrier for the germ plasm, which, if some small over-simplification is allowed, continues unchanged and will in due course release from itself ova, which when fertilized will initiate the second generation. In effect, the germ plasm not merely reproduces itself, but also ensures its own continuance by building around itself a body. The body perishes with each generation, but the germ plasm does not. The germ plasm is thus potentially immortal. Now, since this point is quite fundamental to all that follows, it will be well to recapitulate somewhat and see how the theory of the "continuity of the germ plasm" came to be formulated.

When Darwin formulated his theory regarding the mechanism by which species originate, he made the assumption (which seemed reasonable enough at the time) that when an animal by some accident of life develops a bodily structure that happens to give it an advantage in "the struggle of life," it will automatically pass it on to its offspring. This was a reflection of the theory propounded by Lamarck that "acquired characteristics are inherited." Although this comforting doctrine has been abandoned today except under some very special circumstances, in the state of knowledge as it was then it seemed so reasonable that it was very generally assumed to be true. But not everyone accepted it.

Among those who contributed greatly to the ultimate downfall of the theory was August Weismann (1834 - 1914), a German 22. There is some evidence that somatic or body cells retain the full potential of the germ cells. Writing in Science (vol.126, 1967, p.1338) under the heading "Some Characteristics of a Continuously Propagating Cell Derived from Monkey Heart Tissue," J. E. Salk and Elsie N. Wood reported that it has been possible by the right techniques to isolate heart tissue cells and induce them to go on multiplying indefinitely. The phenomenon suggests that some of the potential for immortality which is characteristic of germ cells may have been retained even by body cells which have differentiated some distance from the originating germ plasm.

M.D. of Canada (vol.10, no. 3, 1969, p.53) reported that Dr. John Gurdon and his co-workers at Oxford had grown fully mature and fertile frogs from single body cells extracted from the intestinal lining of other frogs. With his present technique more than 30 percent of the intestinal cells could be made to grow at least to the tadpole stage.  pg.9 of 17 pg.9 of 17

biologist whose prime interest had been insect embryology. But due to trouble with his eyes, he was forced to abandon the use of a microscope and turned to the theoretical aspects of embryology. In due course he formulated a theory to the effect that a special hereditary substance must be assumed to exist in all animals (the germ plasm), which, unlike the perishable body of the individual (the somatoplasm), is transmitted from generation to generation essentially without modification. This theory came to be known as "the continuity of the germ plasm." (23) He postulated that in each individual the germ plasm was derived directly from the germ plasm of the parents. With comparatively minor qualifications, his theory regarding germ plasm has stood the test of time, a remarkable achievement in view of the fact that virtually nothing was known at the time about such things as chromosomes and genes. Indeed, in a paper by Robert Briggs and Thomas King in an authoritative series of volumes entitled The Cell, the following observation is made, (24) "This part of Weismann's theory dealing with heredity, based as it was on the most fragmentary evidence, has been substantiated to a surprising degree by the genetical work of the succeeding years."

Weismann set forth his theory diagrammatically in the following way: (25)  23. Weismann, August, ref. 6, pp.161f., essay no.4, "The Continuity of the Germ Plasm as the Foundation of a Theory of Heredity," written in 1885.

24. Briggs, Robert, and King, Thomas, The Cell: Biochemistry, Physiology, Morphology, vol.I, edited by J. Brachet and A. E. Mirsky, Academic Press, New York, 1959, p.539.

25. Weismann, August, diagram: see article on "Heredity" in the Everyman Encyclopedia, Dent, London, 1913 edition.  pg.10 of 17 pg.10 of 17

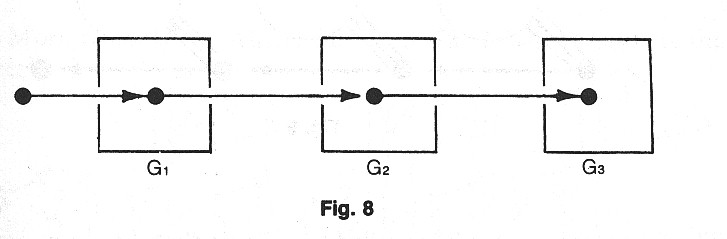

In the center of each square the black dot represents the fertilized seed, the ovum or germ plasm, and the shaded square represents the body which carries it. Weismann proposed that the germ plasm of one generation gives rise directly to the germ plasm representing the next generation, and that this in turn built around itself a body -- still without losing its identity or integrity. He labeled this second body G2, i.e., second generation. The next square, marked G3, simply represents a continuation of the same process. In other words, the body is in each case incidental, in no way being responsible for the germ plasm it happens to carry.

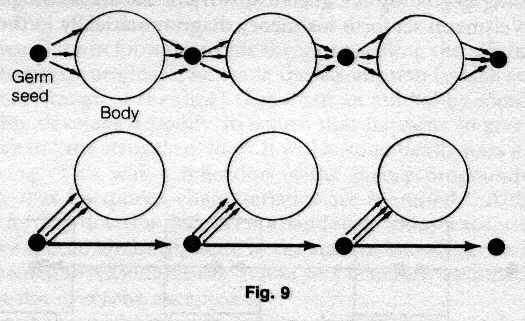

Donald Michie, (26) in a paper entitled "The Third Stage in Genetics," which appears as Chapter 3 in a Darwin centennial volume edited by S. A. Barnett, has a diagram which sets forth in simplified fashion the two alternative views of the history of germ plasm from generation to generation. His diagram with slight modification is as follows:

The first arrangement is intended to indicate that the ovum or germ plasm (black dot) gives rise to a body (shaded circle), which in turn gives rise to a new ovum, which then gives rise to a second body: and so the process goes. In other words, it -- the body -- produces an ovum in order to perpetuate itself. It could be said that in this arrangement the egg is merely the hen's way of laying another hen. 26. Michie, Donald, "The Third Stage in Genetics," in A Century of Darwin, edited by S. A. Barnett, Heineman, London, 1958, p.57.  pg.11 of 17 pg.11 of 17

The second part of the diagram gives a very different picture, for in this case the germ plasm, or seed, incidentally gives rise to a body, but more importantly gives rise to itself as a kind of daughter germ plasm. This daughter in turn builds around itself a body, but only after it has set aside a part of itself for the process of self-perpetuation. In this arrangement it is usually said, in all seriousness, that the hen is merely the egg's way of laying another egg. The first diagram reflects the view held by Lamarck and Darwin; the second, the view held by Weismann and, as Michie points out, by virtually all present-day biologists.

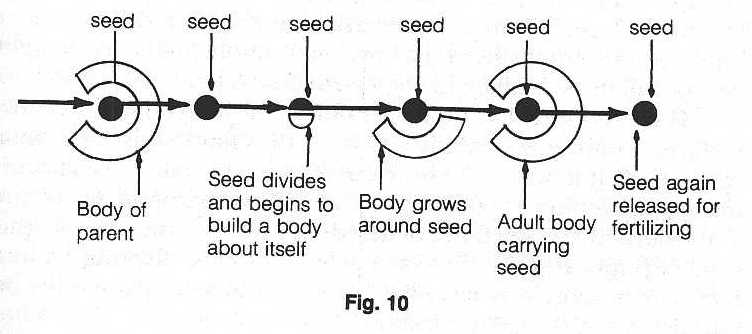

The principle set forth by Weismann has been illustrated diagrammatically in a host of different ways. The following diagram of my own illustrates how each successive ovum builds a body around itself. (27)

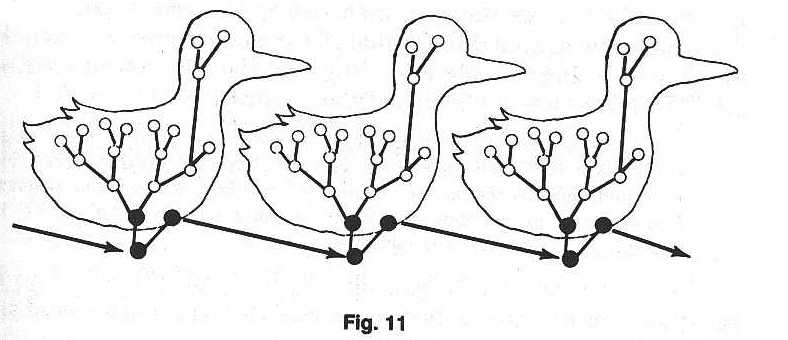

More recently Sir Alister Hardy in The Living Stream shows the diagram depicted above, (Figure 11). (28)

27. "The Nature of the Forbidden Fruit," Part II in The Virgin Birth and The Incarnation, vol.5 of The Doorway Papers Series.

28. Hardy, Sir Alister, The Living Stream, Collins, London, 1965, p.76.  pg.12 of 17 pg.12 of 17

The important point to observe in all these illustrations is that the body does not generate the seed but the seed generates itself and, subsequently, the body which is to convey it. This means that nothing which happens to the body during its lifetime can have any influence upon the seed, except under certain exceptional and well recognized circumstances. Since the body plays no part in the formation of the ova, but merely serves as a temporary housing for it, the body is, strictly speaking, disposable whereas the ova are, strictly speaking, immortal. The seed is, in fact, in no way subject to natural death, nor is it subject to modification through the accidents of life that happen only to the body. It is necessary to repeat that there are circumstances under which the germ plasm may be modified through the agency of the body, but these are not inherent in the total mechanism; such modifications are in the strictest sense "unnatural." The subject is entered into in some detail in another Doorway Paper, (29) but it is necessary to consider the matter very briefly at this point since it has profound implications in the light of events which took place in the Garden of Eden.

It seems clear that Adam did poison his body, thereby reducing its former unlimited viability down to the characteristically mortal state which it now has. This characteristic, mortality, was acquired during his lifetime. He did not begin his life with it. And yet, contrary to the normal circumstance of hereditary transmission, the acquired state of physical mortality was passed on to his offspring and must therefore in some way have had its effect not merely upon the body but also upon the germ plasm.

It seems rather strange to me that, to my knowledge, no Christian biologist has ever given very much thought to this question. As a matter of fact, it has taken a man rather strongly opposed to the Christian view to note this unusual circumstance, no less a man than Sir Gavin de Beer, while reviewing Dobzhansky's Mankind Evolving. (30) In his review de Beer had these words: One wonders if Pauline theologians realize that the doctrine of original sin involves the inheritance of an acquired character, for only genes can be inherited, and, by the nature of the case, neither Adam nor Eve when they first appeared on the scene possessed the character they are alleged to have transmitted to all their descendants. Since the body of an organism is derived from the germ plasm, it can only inherit what has become part of the germ plasm. And since 29. "The Nature of the Forbidden Fruit," Part II in The Virgin Birth and The Incarnation, vol.5 of The Doorway Papers Series.

30. De Beer, Sir Gavin: reviewing T. Dobzhansky, "Mankind Evolving: the Evolution of the Human Species," Scientific American, September, 1962, p.268.  pg.13 of 17 pg.13 of 17

the germ plasm is not derived from the body, it does not normally reflect in its makeup the events which have occurred in the body. Cutting off the tails of generations of rats did not lead to any change in the germ plasm and therefore did not result in the emergence of a race of tail-less rats. It is only when the modification of the body is of such a nature (and the occurrence is rare indeed) that the germ plasm is also modified, that the next generation inherits the modification. An acquired character, therefore, including the condition of mortality acquired by a potentially immortal creature, must occur in such a way that not only the body, but also the germ plasm, has been affected. If the mortal condition acquired by Adam and Eve as the result of eating a forbidden fruit was inherited by their descendants, with the result that death thenceforth passed upon all men, it is necessary to suppose that there was a poison that penetrated to either the male seed or the female seed, or to both.

From what we know of the seed of the woman, the ovum, there is every reason to believe that its original potentially immortal endowment has not been surrendered. Under normal circumstances in mammals the ovum, if it is not fertilized by the sperm, is rejected from the body and to all intents and purposes "killed" in the process. However, by a surprising number of different treatments, it can be made to begin a process of division entirely on its own. This leads to a series of stages of development which to all intents and purposes parallel its history as though it were fertilized by the spermatozoon. The process is known as parthenogenesis, and in a substantial number of fully authenticated instances of animals below man it has led to the birth of a normal offspring. In mammals, however, parthenogenesis always leads to the birth of a female. The reason for this need not concern us in the present context except that it is important to note that parthenogenesis in this technical sense could not have led to the birth of a male child, as in Mary's case.

The evidence that the male seed has this potential is very slender indeed. For one thing it lacks an adequate supply of cytoplasm from which to nourish itself. By supplying this deficiency, (31) spermatozoa have been induced to divide a few times but not to 31. George W. Corner wrote in this connection (The Hormones in Human Reproduction, Athenaeum, New York, 1963, p.19): "If any egg (or ovum) is cut into two pieces, one of which has no nucleus, and the latter is then entered by a sperm cell, it too will divide and become an embryo, though admittedly not as often as in the case of the unfertilized ovum. In this case, the embryo is motherless, from the standpoint of heredity, for it has no egg nucleus in it. This shows that egg stuff, to develop, must have a nucleus and requires to be stimulated, but either an egg nucleus or a sperm nucleus will do."

It is clear that this kind of highly sophisticated manipulation of cells is very different from anything that occurs in Nature, whereas some of the treatments which lead to parthenogenesis could quite conceivably occur in Nature. It is generally agreed that the sperm does not have sufficient cytoplasm to allow it to survive in isolation, the cytoplasm being in effect the store of food which is the source of the energy it must have to divide and multiply. On the other hand, the ovum being several hundred times as large in terms of cytoplasmic content has ample provision made for this. See also on this: A. F. Huettner, Comparative Embryology of the Vertebrates, Macmillan, New York, 1968, p.25.  pg.14 of 17 pg.14 of 17

sustain division such as is observed in the ovum. Consequently, in the case of Adam and Eve we must assume that if they were both initially created immortal, the poison entering their bodies had a more profound effect upon Adam than upon Eve, since Adam's seed seems to have surrendered its immortality whereas Eve's seed has not. Thus, although the woman partook of the forbidden fruit first (1 Timothy 2:14), physical death became the lot of men through Adam, and not through Eve. By man . . . death entered and passed on all men by inheritance. Not because they have necessarily repeated Adam's error (Romans 5:12), but because the seed of the man appears to be the carrier of the element of mortality. In some way the union of the seed of the man with the seed of the woman, while leaving the germ plasm intact, has the effect of robbing the body which the germ plasm builds around itself of its original immortal endowment.

Thus it has come about that while every child born of woman down through the centuries by natural generation has been doomed ultimately to die, the potential for the recovery of the original immortal condition of Adam has never been lost. The seed of the woman has been preserved intact from the very day Eve was taken out of immortal Adam, needing only to be vitalized by some other means than the seed of the man in order to recover once more the original immortal potential of man as created.

The Book of Job reveals many remarkable insights into the problem of man's redemption. Two questions are sometimes asked in one breath, which though seemingly unrelated are yet indissolubly linked together. Such is the case in Job 25:4. One of Job's "comforters," Bildad, perhaps not altogether realizing the significance of his own juxtaposed questions, asks, "How then can man be justified with God? Or how can he be clean that is born of a woman?" The question is a profound one indeed, for man's redeemer must himself be man and therefore born of a woman; but he must not stand under the same judgment that all other men born of woman inevitably stand. Job had already established the fact that one cannot bring a clean thing out of an unclean (Job 14:4) ,and therefore the question arose, How can one hope to find a redeemer born of woman who is not himself already under condemnation as unclean  pg.15 of 17 pg.15 of 17

and therefore unfit to act as substitute? Man that is so born is doomed to die on this very account and can never substitute for dying man. Perhaps for all his insight, Job did not perceive the significance of the promise with respect to "the seed of the woman," for this prophecy regarding the virgin birth (Isaiah 7:14) was yet far in the future. That seed was Christ (Galatians 3:16), supernaturally conceived by the overshadowing of the Holy Spirit and born of the virgin Mary. It was a seed inherited by Mary from Eve, and therefore of Adam. David says that he was conceived in sin (Psalm 51:5) and shapen in iniquity. But Jesus was conceived by the Holy Spirit and shapen unto perfection (Hebrews 10:5). The word translated "prepared" in this passage is the Greek word katartizo. Its use here is very important, for its meaning is always fundamentally the same, namely, "to be made perfect." It is used of the members of the body of Christ who are to be perfectly joined together (1 Corinthians 1:10). Paul uses it of our individual "perfecting" (2 Corinthians 13:9), and again of "the perfecting of the saints" (Ephesians 4:12).

David was born to die, his life span being limited to a bare three score years and ten (Psalm 90:10); Jesus was born "after the power of an endless life" (Hebrews 7:16). David was born, as we all are, "sinful flesh"; Jesus was born only in its likeness (Romans 8:3). David's father was a mortal descendant of Adam who conveyed the stream of physical defect in his seed and contaminated the seed of his wife in her conception of David. He who was a greater than David was the Son of a Father, who conveyed through the Holy Spirit to the seed of the woman, Mary, no physical defect and no stream of mortality.

Only an immortal creature is free to surrender life voluntarily as an act of self-sacrifice. All other acts of human self-sacrifice made by mortal creatures constitute only a choice of the time of dying, for death must come sooner or later in any case. Every purely human sacrifice is, after all, only a premature death, a shortening of life. Mortals can surrender a few years of expected life, but this is all they can do. Only an immortal can surrender life itself. Jesus did not merely choose the time to die and therefore by how much He would shorten His expected life span. He was in a position to choose whether to die at all. In this, mortal man has no choice whatever.

It was thus necessary to find a substitute who was truly man, that he might stand in man's stead. But it was also necessary to find a substitute who, unlike man, was constitutionally under no sentence of death. We ourselves cannot truly surrender as a voluntary act that which we are doomed to lose, because sentence of death has already been passed upon our bodies by their very nature. No man can by  pg.16 of 17 pg.16 of 17

any means redeem his brother, for he is already under the same condemnation that his brother is (Psalm 49:7). Man requires as a redeemer one who, while being truly representative of him, is yet free of this condemnation, not only the condemnation of being a sinner, but the position of being mortal. It is essential to remember that Scripture recognizes the importance to man of his body, as well as his spirit. His body was created as an appropriate temple to house his created spirit. It is not incidental but fundamental to his very being as a man in God's sight. God has evidently attached just as much importance to man's body as to his spirit in that Jesus was "made flesh" as man, not merely introduced into our world as pure spirit. It was in His body that on the tree He bore our condemnation and then was resurrected bodily, not merely spiritually. As man He took a body to heaven. Body and spirit alike are redeemed by a substitutionary sacrifice. Calvary had to fulfill the conditions required to save man's body and man's spirit, not his spirit only. The resurrection of the body is essential to the continuance of the whole man, saved or unsaved.

Thus God, in His creative wisdom, set the stage for man's redemption, the redemption of his body as well as his spirit, first by creating an Adam who was potentially immortal encompassing in himself both seeds, male and female, and then by separating Eve out of him and entrusting to her one of the two seeds, fashioning for her a body specially designed to preserve that seed intact and uncorrupted through each successive generation. The record of these things is full of light when we have the key. We need only to take it and believe it. There is nothing arbitrary here, nothing purely miraculous, as though God worked only by miracle, nor purely natural as though here were no need for God's intervention. Here faith leads to understanding, as we observe how the supernatural acts upon and complements the natural. We are able to see, in a measure, how the Virgin Birth came to be the means whereby God recovered within the stream of truly human life a Second Adam to redeem the children of the First Adam.

It remains now to explore how it was that this perfect little body, when Mary's full time was come, became the temple of God in the Person of Jesus Christ His Son.

pg.17

of 17 pg.17

of 17  Copyright © 1988 Evelyn White. All rights reserved

Previous Chapter Next

Chapter

Copyright © 1988 Evelyn White. All rights reserved

Previous Chapter Next

Chapter

|