|

Abstract Table of Contents Part I

Part II

Part III

Part IV

Part V

Part VI | Part IV: Remrkable Biblical Confirmations from Archaeology Chapter 1 Abraham and His Princess ALONG WITH Adam and Noah, Abraham surely stands out in one's imagination as a giant, head and shoulders above his contemporaries. He moved across the stage of history with the quiet dignity of a prince among men, men who knew his stature so well that he himself never felt the need (except in one circumstance) to protect himself.

Abraham's story occupies slightly over thirteen chapters of the Book of Genesis, a space greater than that given to anyone else (3) and which in this context is more important still, consisting of a record filled with circumstantial details of such a nature that the possibilities of mis-statement, or the introduction of fictitious events and customs, of anachronous local coloring, and of wrongly identified or related individuals, are almost unlimited. Yet archaeology has confirmed or shed light upon these details in every particular. The confident assertions once made by the Higher Critics that Abraham was probably a fictitious figure (since his name had not appeared in any ancient inscriptions) have been proved completely wrong. The details of his life which were supposedly the invention of fertile minds who sought to give dignity to the "founder" of their own nation, the Jewish people, have been set in their true historical perspective. Time and again details of this record were declared to be in error. But no sooner had such positive declarations been made than God seems to have delighted to confound the experts by allowing the discovery of some evidence which not merely demonstrated the correctness of the narrative but even proved that the record itself must have been written at the time, since the circumstances shortly after were altered. This can be illustrated for several incidents in the life of Abraham. 3. This is true if we exclude that portion of the text associated with Moses, which is really only a record of instructions given to him and by him and not strictly biographical material.  pg 1 of 27 pg 1 of 27

Although this is not strictly the starting point of Abraham's story, I should like to begin with his stay in Haran. It is customary to look upon his stay here as an example of partial obedience. The Lord called him to go into the Promised Land, we are told; but he went only halfway. This may be a justifiable interpretation perhaps, but the text itself seems rather to indicate that Terah, his father, was the one who decided to make the first move. In Hebrews 11:8 it is said that Abraham, when he was called to go into a place which he should after receive for an inheritance, obeyed. Genesis 12:1 indicates that the "call" came rather when Abraham was already in Haran rather than when he was in Ur. The text of Genesis 11:31 reads, "And Terah took Abram his son and Lot. . . and Sarai . . . ; and they went forth from Ur of the Chaldees to go into the land of Canaan; and they came unto Haran, and dwelt there."

Now, Haran was not just a city like any other

city, but had a special significance for the traveller, a significance

underscored by the fact that Haran bore a unique relationship to the city

of Ur. In the first place, the name  ,

Kahar-ra-nu, is not Semitic, being a derivation from the Sumerian

word, Kharran meaning "a road". (4)

In a bilingual vocabulary this word is given as an equivalent of the Assyrian

words Daragu and Metik, the first being related to the Hebrew ,

Kahar-ra-nu, is not Semitic, being a derivation from the Sumerian

word, Kharran meaning "a road". (4)

In a bilingual vocabulary this word is given as an equivalent of the Assyrian

words Daragu and Metik, the first being related to the Hebrew

,

meaning "a road" or "a way"; and the second related

to a further Hebrew word, ,

meaning "a road" or "a way"; and the second related

to a further Hebrew word,  ,

which means "to transfer", in the sense of transport. Kharranu

is also an ideographic reading of the sign ,

which means "to transfer", in the sense of transport. Kharranu

is also an ideographic reading of the sign  ,

the ancient form of which was ,

the ancient form of which was  ,

clearly representing a crossroads. It was, therefore, a city which derived

its name because it lay on one of the great road junctions of the Tigris-Euphrates

Valley and other roads from the north and west. Even today, from its various

gateways roads branch off to Mosul, to Diarbeker, Berijik via Ofra to

Balis and other places. In ancient times the roads from Carchemish and

Nineveh and Babylon all met here. ,

clearly representing a crossroads. It was, therefore, a city which derived

its name because it lay on one of the great road junctions of the Tigris-Euphrates

Valley and other roads from the north and west. Even today, from its various

gateways roads branch off to Mosul, to Diarbeker, Berijik via Ofra to

Balis and other places. In ancient times the roads from Carchemish and

Nineveh and Babylon all met here.

But even more important, though these circumstances would be quite sufficient to explain why Terah settled here, is the fact that it was chiefly noted in ancient times as being the site of a well-known temple of the Moon-god, Sin -- the same deity that was the divine patron of Ur. This temple was called  , Bit-Khul-Khul, which is taken to mean "The House of Great Brightness", the reduplication being intended , Bit-Khul-Khul, which is taken to mean "The House of Great Brightness", the reduplication being intended 4. This is dealt with interestingly by W. St. Chad Boscawen, "Historical Evidences of the Migration of Abram," Transactions of the Vietorian Institute, vol. 20, 1886, p.117-18. The information given is most complete.  pg.2 of 27 pg.2 of 27

to signify superlative light. A cylinder of Nabonidus of Babylon, who was the father of Beltshazzar of Daniel's time, refers to it as "The House of Sin Which is Within the City of Kharran". He has occasion to mention it because he records his restoration of it. We find, therefore, a very close link of a special kind (i.e., religious) between Ur and Haran, so that Terah who worshiped this deity found himself very much at home. (5)

However, this is still not the whole story. For although one has a picture of gross paganism and obscene forms of worship associated with all Babylonian religions, there is evidence from an inscription of Nabonidus that even in his time, many centuries later, there were still men who saw through the corrupted outward forms an inner sublime truth. It was as though, as Paul put it in Romans 1:28, they held the truth (the Greek even allows the word retained) in unrighteousness, i.e., they still maintained fragments of an earlier pure faith encrusted with the corrupting influences of later centuries. At any rate, the following prayer, the author of which was none other than Nabonidus himself, was found in the ruins of the temple of the moon-god, at Ur: (6) Oh Sin, Lord of the Gods, King of the Gods of Heaven and Earth, [and] God of the Gods who inhabit the heavens, the mighty ones, for this temple with joy at thy entrance, may thy lips establish the blessing of Bit Sagila, Bit Zida, and Bit Giz-nugal, the temples of thy great divinity. Set the fear of thy great divinity in the hearts of his people that they err not; for thy great divinity may their foundations remain firm like the Heavens. As for me, Nabonidus, King of Babylon, preserve me from sinning against thy great divinity, and grant me the gift of a life of long days; and plant in the heart of Bel-sarra-utzur [ Belshazzar], the eldest son, the offspring of my heart, reverence for thy great divinity, and never may he incline to sin. With fulness of life may he be satisfied.

Such, then, at a much later date was the spirit of one man worshipping in Ur and restoring a temple to this God of Gods in Haran. Long before, the spirit of worship may have had even purer and clearer light both in

5. There was a time when it was held by scholars that the Hebrew people originated not in Mesopotamia, Abraham's birthplace, but in Arabia. I do not believe that this latter view is any longer held with much conviction. Linguistic evidence is positively against it. For example, the Arabic word for "ostrich" is na'am, and Arabia is the home of this creature. But the Hebrew word for ostrich is ya'en. Similarly, the wild ox is called in Hebrew re'em which appears in Assyrian as remu. This word is also found in Arabic, but here it is applied to a quite different animal. The explanation of this is probably that the Hebrews and Assyrians shared the word for the same animals, but the Arabs, emigrating from a country such as Babylonia, carried the name with them into their new land but, finding no wild oxen there, applied it to another animal. See John Urquhart, Modern Discoveries and the Bible, Marshall Brothers, London, 1898, pp.311 ff. and 323ff.

6. Given by Boscawen, ref.4, p.113.  pg.3 of 27 pg.3 of 27

Ur and Haran, so that perhaps Abraham was not brought up altogether without the influences of some quite devout worship. And perhaps the very grossness and depravity of Canaanite religion, which would presumably be much better known among the people of Haran who were closer to it than the people of Ur a thousand miles away, discouraged Terah from going any further. But when Terah died in Haran, then the call came to Abraham to undertake by faith what his father had feared to do.

Abraham then set out from Haran taking with him his family and servants. Like Paul, he was a citizen of no mean city. The civilizations of both Ur and Haran were complex and well-developed. He was a city dweller originally and not unnaturally, therefore, he looked not for a country but for a city (Hebrews 11:10). His first settlement in the Land of Promise appears to have been uneventful and fairly brief, being terminated by a famine which led him to journey on into Egypt. As he entered this ancient land, he realized that his wife, being such a beautiful woman, might be a source of danger to himself since he supposed that some of the Egyptians in authority with whom he expected to do business would desire her for themselves and might take steps to have himself put out of the way.

Looking at a picture of women in Palestine of not so long ago who were veiled so that only their eyes show, one might wonder how the Egyptians would be able to "look upon her" and "see her". The critics jumped on this immediately and said, "This is a fairy story, a projection from a much later age when women had more freedom." The fact is that the monuments show that the later customs of the East were not those of ancient Egypt, whose women moved about freely and did not conceal their faces. Indeed, they dressed -- to use a modern term -- revealingly; their clothing was often quite diaphanous. Had this story been written centuries later by a Jew living in Palestine, he would surely either have added an explanatory note saying why her beauty was so evident (for the benefit of his contemporary readers) or he would never even have imagined such an event.

The critics also pointed out that Abraham's suspicions regarding the intentions of the Egyptians seemed in sharp contrast to the known fact that at this particular period in their history, the Egyptians were quite open and friendly with foreigners. (7) However, archaeology has shed a wonderful light on even this element in the 7. Joseph Free, in Archaeology and Bible History (ref.1, p. 54, footnote 12) gives the evidence of this in some detail from ancient authorities.  pg.4 of 27 pg.4 of 27

story, for there has been found an ancient Egyptian papyrus, which is now in the British Museum, which is probably the oldest known bit of fiction (?) in the world. (8) It is called "The Story of the Two Brothers". In this story, the Pharaoh sends two armies to fetch a beautiful woman by force and then to murder her husband. The king is not described as a tyrant nor a scoundrel, is beloved by his people and at his death passes unchallenged into heaven. The action is prompted by members of his court. It will be noticed in the case of Sarai that in similar manner it was the princes of Pharaoh who saw her (Genesis 12:15) and commended her to Pharaoh, who then took her into his house. And Abraham was treated very well, since the king imagined he was her brother only, and therefore her special guardian.

A word seems in order here about Abraham's statement that Sarai was his sister. Twice Abraham used this device to secure his own safety, and in the second instance (Genesis 20) he added by way of justification the rather cryptic statement that "indeed she is my sister; she is the daughter of my father but not the daughter of my mother." What did he mean by this?

The background of this perfectly true observation is a little complicated but worth taking time to examine, because it only goes to show that there is no part of this early record which cannot be taken quite literally. This

is a faithful record. It is exactly what Abraham could have said in view of what we now know about family relationships both of Abraham's time and even of recent times among non-Indo-European peoples.

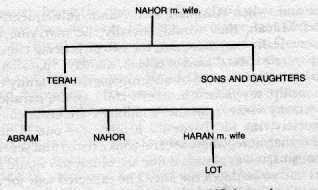

In Genesis 11:25-27 we have the following genealogy: And Nahor lived after he begat Terah an hundred and nineteen years, and begat sons and daughters.

And Terah lived seventy years and begat Abram, Nahor, and Haran.

Now these are the generations of Terah: Terah begat Abram, Nahor, and Haran; and Haran begat Lot.

This can be set forth schematically as follows:

8. Urquhart. John, ref.5. p.349.  pg.5 of 27 pg.5 of 27

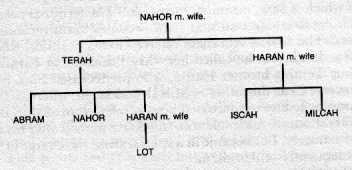

Up to this point, the sons and daughters of Nahor who were Terah's brothers and sisters are not named, but information given in the following verses provides very good grounds for believing that one of these was named Haran. We shall examine this shortly, but for clarity we now modify the above genealogy as follows (verses 28, 29):

It will be noted that Terah's brother, Haran, had two daughters, Iscah and Milcah. The former of these, Iscah, was Sarah by another name. This identification is very widely agreed upon, was accepted in Jewish commentaries, and is assumed by Josephus in his Antiquities (Book I, vi, 5).

It may appear to the reader that large liberties are being taken with the text, but this is not really the case. Like many others, the Jewish people commonly accepted the principle that if a man's brother married a woman and subsequently died before the children were married, he took his brother's place and became in effect both her husband and the father of her children. This is the basis of the Pharisees' hypothetical question in Luke 20:27-38. If therefore Terah's brother Haran had died, the duty of becoming in effect the father of Iscah and Milcah would automatically devolve upon Terah. Terah's "new" children would then become sisters to his own  pg.6 of 27 pg.6 of 27

sons and, when Abraham and Nahor subsequently married Iscah and Milcah, they would, socially, be marrying their own sisters. Genetically they were not, the two girls being cousins. However, they were a special kind of cousin, namely, "parallel cousins". The term has been invented by anthropologists to signify the following relationship: my father's brother's children are parallel cousins; by contrast, my mother's brother's children are cross-cousins. In a Semitic society, the ideal wife for a man was one of his parallel cousins. Furthermore, where several sons existed and several female parallel cousins, it was assumed that the oldest son would marry the oldest girl and so on down the line. The expected wife for Abraham would therefore be his Uncle Haran's daughter of comparable age.

Now this seems a little complex, but it is particularly striking in this instance, because even today among many Arab tribes in all their love stories the man looks upon his paternal uncle's daughter as his "princess". (9) This is the term by which he refers to her in his poetic moments. In Hebrew the word for prince is Sar, the feminine form of which is Sara, meaning "princess". The terminal possessive pronoun my is a long i so that Sara becomes Sarai meaning "my princess". This is how Abraham referred to his beautiful wife. Her name was Iscah, but he called her "My Princess" or Sarai.

Thus Terah's brother Haran, who predeceased him, is identified in verse 29 as the father of Milcah and Iscah, whereas Terah's son Haran, who also predeceased him, is referred to as the father of Lot (verse 31). Because his son Haran (no doubt named after his uncle) died prematurely, Lot became in a special sense the charge of Terah and subsequently of Abraham.

It is interesting to find that the American Indians adopted virtually the same forms of social responsibility. (10) According to Lowie, the Seneca reckon the father's brothers as "fathers", exactly as Abraham and Nahor, reckoning Haran as a father, would look upon Iscah and Milcah as sisters. The same is true in Hawaii, where a single word exists for "father" and "father's brother", the two individuals being considered as standing in the same relationship simply because if the one dies, the other assumes his position.

So when Terah's brother died, Terah took his brother's wife and became the father of his brother's children. Because he was also the father of Abraham, this allowed Abraham to say with perfect truth (though with ulterior motives) that Sarai, his princess, was indeed his sister, being the daughter of his own father -- but not the 9. As reported to me personally by Ali Tayyeb, himself a native of the Muti Ali of Arabia, and referred to by Roland B. Dixon in this ethnographic study of this people published in 1926(?).

10. Robert H. Lowie, Social Organization, Rinehart, New York. 1948. p.62.  pg.7 of 27 pg.7 of 27

daughter of his own mother. There is, therefore, not the slightest element of invention here insofar as the record of Genesis goes. Genesis 11 gives us sufficient information, if carefully read, to see that there is nothing imaginary about the circumstance which so compounded Abraham's relationship with his own wife.

Only one further observation seems appropriate here. And that is, every brother in a society of this nature is given a particular responsibility for the sister who is next to him in age. He bears a special protective relationship toward her and must approve her husband. He will, moreover, be called upon to chastise her children if necessary -- while the husband will not be allowed to do so. It was thus important to curry the favour of any brother who was manifestly the protector of the sister whose hand might be sought in marriage, in which position Abraham must have appeared in the eyes of Pharaoh. This is why Abraham felt sure of his own safety, and indeed of being favoured by Pharaoh or anyone else who might be in a position to desire Sarai. And it worked!

By contrast with the treatment that Abraham received, there is an early record of another visitor to Egypt who did not fare so well. (11) The papyrus recording this story was formerly in the Berlin Museum. It reports how a foreign artisan enters Egypt, only to find his ass seized by an inspector. He appeals to the governor, who in turn appeals to the King, Neb-ka-ra of the eleventh dynasty. The result is that the Pharaoh of the time seizes the foreigner's wife and children and orders so much food and water to be given to the artisan. This seems rather unfair, but apparently it was quite customary and was accepted as proper. In Abraham's case, it is evident that the Pharaoh was in a sense a God-fearing man, for when he discovered by divine intervention the true relationship between Sarah and Abraham, he rebuked Abraham for telling lies, restored him his wife, and sent him away unharmed. 11. Urquhart, John, ref.5, p.350. It may be pointed out that the treatment of the husband was possibly much less unpleasant to him than we might suppose. The famous Madame de Pompadour (cf. a book of that title written by Nancy Mitford, Reprint Society of London 1954) --w hose life was (if the word may be used in an entirely non-Christian context) "saintly" indeed despite her position as the mistress of Louis XV -- was married to a man whom the King recompensed for the taking of his wife by providing him with complete social security. At the very end, when she was near the point of death, the church asked her to offer to return to him, which she did -- though she loved the king with a completely genuine love. One must remember the "times" in which such things occurred. However, her husband was so free and "well off" that he refused her. There was no actual love in any case between the husband and wife. Perhaps the same was true in this case and the visitor to Egypt gladly surrendered his "wife" for a royal price.  pg.8 of 27 pg.8 of 27

And now with respect to the presents: sheep, oxen, asses, and camels. A German critic, von Bohlen maintained that some of the animals mentioned were quite unknown in ancient Egypt. The narrator, he argued, named animals from his own country which Abraham could not have received in Egypt. He said nothing of receiving horses, which were exceedingly plentiful in the valley of the Nile: but he speaks of receiving sheep -- which are as rare as camels according to testimony from antiquity, he said -- and asses were thoroughly disliked on account of their colour!

The fact of the matter is that on the monuments of the twelfth dynasty, sheep are pictured and were, therefore, well-known at the very time of Abraham's visit. Indeed, mention is made in inscriptions of large flocks forming part of the wealth of Egyptian nobility, and the god Num is frequently portrayed with a ram's head.

As for the oxen, even the geologists (Lyell, for example) in their excavations found the bones of oxen at great depth showing that they had been known from very early times. Ameni, an official of the twelfth dynasty, boasts that as governor of the district of Sahour, he had collected a herd of three thousand bulls with their heifers. Indeed, the animal was worshiped. . . .

The critics fare equally badly with regard to the ass, which is to be seen pictured on the tombs of the Pyramids. It is represented on the most ancient monuments, and wealthy Egyptians possessed hundreds of them. Khafra-Ankl, a high court official of the builder of the second pyramid, at Gizeh, possessed 760 asses.

The camel, curiously enough -- although it was employed in Egypt from remotest antiquity, being used for carrying merchandise and even apparently for entertainment (being trained to dance!) -- was for some reason excluded from representation on monuments. (12) It was not the only example of this, for hens, which were raised in large numbers, were similarly tabooed for portrayal.

Von Bohlen stated categorically that the horse was well-known and prized in Egypt and therefore the omission of any mention of it in this instance shows the writer's ignorance of the facts. Now, when Moses wrote, the horse was well-known and highly prized in Egypt. Were not the horsemen and their riders overwhelmed in the Red Sea? Then why the omission in this case? The fact is that we now know from the monuments that the horse was unknown in Egypt before the invasion of the Shepherd Kings, an event which occurred later than Abraham's visit. Pictures of horses appear for the first time among the hieroglyphic characters of the eighteenth 12. Joseph Free made a special study of this question which he reported in the Journal of Near Eastern Studies, University of Chicago, July, 1944, pp.18 7-93, under the title, "Abraham's Camels".  pg.9 of 27 pg.9 of 27

dynasty. In fact, it is likely that the success of the Shepherd Kings was largely due to their possession of horses, which inspired terror in the hearts of Egyptians when they first encountered them. Thereafter horses became exceedingly plentiful. Thebes, Memphis, Hermopolis, and most of the great cities of Middle Egypt contained breeding studs. The possession of many horses was the hallmark of aristocracy, and indeed it appears that the Pharaohs encouraged the practice, rewarding the owners of well-kept stables and even punishing those who did not take care of their animals.

The absence of the mention of the horse is therefore one of the most valuable circumstances in connection with Abraham's visit in Egypt, for it indicates that this visit took place before the invasion of the Shepherd Kings, and about the time of the twelfth dynasty, which lasted from around 2000 to 1788 B.C. The Hyksos (Shepherd Kings) with their horses did not arrive until around 1600 B.C.

We have spoken of the amount of detail given in these chapters which deal with Abraham, and Genesis 14, recording his rescue of Lot, is certainly no exception. Names, places, and events are described so fully that no one but an eyewitness could have achieved the effect. Yet, because at the time of their writing the Higher Critics had seen no archaeological findings to support these details, nor inscriptions or tablets bearing the names of the chief characters, and no evidence that Elam (which figures so prominently in the story) ever held the dominating place in the Middle East which is ascribed to it here, they stated categorically that the whole story was a myth. But little by little they have been proved absolutely wrong: the story has been vindicated in every essential detail. And when this became undeniable, the characteristic reaction of the critics was to say with all the assurance in the world that a post-exilic writer who lived centuries later had done some research into Babylonian antiquities and come up with a reconstruction! It is possible, of course. But surely this is to adopt a policy of accounting for the evidence in the least likely way conceivable.

By way of background, it may be remembered that in Genesis 13 we have a picture of Abraham and Lot, both with enormous herds and flocks, finding their herdsmen in conflict when they settled too near to each other. By agreement Abraham and Lot parted company, the former remaining on higher ground to the west of the Jordan Valley, whereas the latter went down into the valley, which as exceedingly fertile, and settled toward Sodom. It may be mentioned in passing that the Land of Canaan does not seem to have been very densely  pg.10 of 27 pg.10 of 27

populated at this time. As Abraham said, there was plenty of room for everybody. The cities were quite small, and their kings were really more like mayors or chieftains. The number of people involved in the subsequent conflict cannot have been very great, since Abraham set out in pursuit with only a few hundred men. This may come as a surprise, but it also helps to set the stage a little more realistically and to discourage one's imagination from picturing five huge armies under five powerful monarchs engaged in a life-and-death struggle with four equally large armies under four Jordanian Valley kings. There is evidence for this somewhat reduced picture from the figures which are given both of casualties and captives taken by a conquering Pharaoh at a later period. C. H. Irwin points out that a pharaoh as late as Thotmes III in an account of his great battle at Megiddo (c. 1479 B.C.) records that only 83 men were killed and 340 taken prisoner. (13) Of all the towns and fortresses of Syria which he captured, he took only 707 prisoners who were not slaves. These figures suggest that the engagements of enormous numbers of men in battle belong to a much later date in a history.

By contrast with these figures, the vast numbers of animals which were owned by Abraham and Lot (Genesis 13:2, 6) -- running into thousands if Job 41:12 is any indication (14,000 sheep, 6,000 camels, 2,000 oxen, etc.) -- may seem to be in error on the other side of the ledger. However, there are modern parallels. Zane Grey, (14) no mean authority in this area, refers to a certain Colonel Maxwell who had an immense tract of land as a ranch which reached the zenith of its fame in 1861, stretching at its maximum some sixty-five miles! He employed about 400 men, mostly Mexicans. At this time, 1861, it was estimated he had 400,000 sheep, 50,000 cattle, and 10,000 horses. The number of other animals he never even bothered to estimate. David Livingstone reports a similar case from Africa, in which a certain Colonel Pires, (15) who began as a servant in a ship, by hard work became the richest merchant in Angola, possessing thousands of cattle, and able in an emergency to appear in the field with several hundred armed slaves. He refers to this man as a "merchant prince" -- a title surely reminiscent of Abraham. If the reader will remember the number of armed men whom 13. Irwin, C. H., "The Bible, the Scholar, and the Spade," Religious Tract Society, London, 1932, p.51.

14. Grey, Zane, Fighting Caravans, Grosset and Dunlap, New York, pp.143ff.

15. Livingstone, David, Missionary Travels and Researches in South Africa, Harper, New York, 1858, p.460.  pg.11 of 27 pg.11 of 27

Abraham assembled in Genesis 14, the number of men retained by Colonel Maxwell, and the number of men in Colonel Pires's establishment, the similarity is at once apparent. It suggests that all three men lived in rather similar circumstances. The implications of those verses in Genesis 13 which set the stage are therefore not the least bit unreasonable.

Like Maxwell and Pires, pioneers in new territory, Abraham expanded freely his settlement of the highlands west of the Jordan, and Lot went down into the valley with his great herds -- neither of them being challenged by settlers already there.

Now, Genesis 14 records the campaign of an Elamite king in Palestine who captured Lot but was afterward, to use an army term, " thoroughly clobbered" by the patriarch, who took a dim view of the situation. Apparently the kings of Sodom and Gomorrah (cities in the Plain where Lot had settled) had been subject for some twelve years to a certain Chedorlaomer, king of Elam, to whom they regularly paid tribute. When tribute failed to appear at the proper time, Chedorlaomer crossed the Euphrates with an army and called to his support three other kings who had apparently also been subject to him in Babylonia: Amraphel, king of Shinar; Arioch, king of Ellasar; and Tidal, who is referred to as "king of the nations".

The Elamite king's campaign was a masterly one. He and his allies first attacked the nations in the north so as to leave no enemy in the rear, passed down east of the Jordan Valley, swept around by Mount Hor on the south, and then turned northward again through the territory of the Amalekites and the Amorites. Having carried everything before him, he suddenly appeared at the south end of the valley and attacked the cities of the Plain.

The route taken by the four kings, following this line parallel to and east of the Jordan, was fastened upon by the critics as evidence of the legendary character of the story. But in the course of time, archaeologists discovered a series of early and middle Bronze Age mounds, some of which were of considerable size, particularly at those places mentioned in the Bible -- namely, Ashtaroth, Karnaim, and Ham. Here Dr. Albright (16) discovered in 1929 centres of population which must have been thriving between 2500 and 1600 B.C., 16. Also reported by W. F. Albright in The Archaeology of Palestine and the Bible, Fleming and Revell, New York, 1935, p.133; and by the same author, in the Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research, no.35, 1929, p.10ff  pg.12 of 27 pg.12 of 27

belonging to the Zuzims, the Emims, and the Rephaims. It is not certain whether these peoples had favoured the rebellion of their valley neighbours, but at any rate Chedorlaomer evidently considered them a sufficient threat that their cities were so devastated in the campaign it appears they were abandoned not long afterward and never re-inhabited.

In this route of attack, Abraham had naturally been bypassed, though undoubtedly he heard what was going on. Meanwhile, the kings of Sodom and Gomorrah and the king of Admah ( the present el-Damieh), the king of Zeboiim, and the king of Bela (Zoar) joined forces and gave battle with these advancing forces from Babylonia in the Vale of Siddim. As Genesis 14:9 succinctly puts it, "four kings with five". It does conjure up in one's mind an enormous conflict -- and for them, it undoubtedly was.

The story tells the sad result, for the five native kings were hopelessly put to flight and Chedorlaomer and his cohorts chased them up the valley and into the hills and spoiled them of everything they could lay their hands upon. The biblical account, which occupies only a few verses, nevertheless is vivid indeed: and Lot suffered with his neighbours, losing virtually everything he possessed.

Abraham heard that his "brother" had been taken captive, and he armed his own servants, 318 in all, and started after Chedorlaomer. The victors had such a head start that he did not overtake them until they had reached Dan, over 150 miles to the north. Having done so, he split into companies (one cannot divide three hundred men too many times!) and launched a surprise attack by night. And he won a resounding victory. The record says simply, he brought back all the goods and also brought again his brother Lot and his goods. . . .

So having reviewed the campaign, we may now examine the evidence from archaeology for the existence of these various kings. To begin with, the narrative allocates a superior position to Chedorlaomer, king of Elam.

Not only was he able to command the support of three Babylonian kings, but also to collect tribute successfully for some twelve years from five vassal kings a thousand miles away in Palestine. As we have noted already, the critics were quite confident that at no time in history did any Elamite king exercise such unchallenged sovereignty over Babylon and Palestine. But it now appears that he did, that indeed at this very time Elam was supreme from the Persian Gulf to the Caspian Sea and from the eastern borders of Persia to the Mediterranean.

Some of this evidence is indirect but rather interesting. An inscription of Assurbanipal, the grandson of

pg.13 of 27 pg.13 of 27

Sennacherib, was found recording an early campaign into Elam in which, having captured the capital city of Susa, he succeeded in recovering a statue of the goddess Nana, which had been carried away from Babylon by a man named Kudur-Nankhundi, king of Elam, 1,635 years previously. (17) By extrapolation, this would put the Elamite conquest of Babylon somewhere about 2280 B.C., or perhaps 200 years before Abraham entered Canaan. Moreover, the Elamites had also conquered Palestine. George Smith found a brick at Ur upon which was an inscription of a king called Kudur-Mabug. (18) This man claims the title of Adda-Martu, literally, "Father of the Land of the Setting Sun", a title which according to Boscawen is equivalent to the Assyrian Sar Akharri, king of Syria. (19) The same inscription gives him the title of king of Elam. Another inscription of his gives him the title of "Father of the Land of the Amorites", i.e., Palestine. Thus, from the number of inscriptions of his now known, he appears to have been an important individual. So Elam did at one time hold sway, and a king of Elam, as Genesis 14 indicates, could very well have undertaken the campaign recorded of him here.

Moreover, the biblical name of this monarch is composed really of two words, Chedor and la'omer. The first part of this name is a transliterate form of Kudur, common to the other two Elamite kings, whom Schrader terms collectively the "Kudurid" dynasty. (20) The second part of the name is undoubtedly to be identified with a word lagomer (the hard breathing in the Hebrew being represented by the guttural g) which in the form La-ga-mar-ru was the name of an Elamite goddess. "Chedorlaomer" is therefore a perfectly proper transliteration of Kudur-lagomer, which means literally "a servant of Lagomer " As a matter of fact, the Septuagint writes this name as "Chodollogomor." This takes care of one of the names, for it is found to be perfectly consonant with the titles of other Elamite kings and such a one might well have been as powerful as the Bible indicates.

It was not long afterward that evidence was found for the existence of a contemporary king whose name was Eri-aku of the city of Larsa. (21) The word for city is alu in Babylonian, and the form Ellasar is perhaps simply "the City of Larsa." This is analogous to the form Uru-salem (Jerusalem) where uru is a Sumerian word 17. See also Eberhard Schrader, The Cuneiform Inscriptions and the Old Testament, Williams and Norgate, London, 1885, p.122.

18. Urquhart, John, ref.5, p.366; and Schrader, Eberhard, ref.17, p.122.

19. Boscawen, W. St. Chad, ref.4, p.100.

20. Schrader, Eberhard, ref.17, p.122.

21. Boscawen, W. St. Chad, ref.4, p.100.  pg.14 of 27 pg.14 of 27

for "city," so that the compound form really means "City of Salem". Thus Arioch of Ellasar is almost certainly the same as "Eri-aku of the City of Larsa". Moreover, this same Eriaku was the son of the Elamite king named Kudur-mabug. (22) At least two inscriptions are known in which Kudur-mabug is said to be the father of Eriaku. One of these, which is now in the British Museum, is an address to the goddess of Zariunu in which Eri-aku, the Great One (Lugal) of Larsa, asks for the preservation of both himself and of Ku-du-ur Ma-bu-uk (i.e., Kudur-mabug), his father. Evidently the Elamite king, Kudur-mabug, appointed his own son as lord of one of his cities, who, as such, according to biblical usage, was quite properly referred to as "king of Larsa".

The situation is complicated a little by the existence of certain other inscriptions (23) in which Kudur-mabug also refers to a son by the name Rim-aku, a son who in a tablet of Hammurabi's (24) is said to have been king of Ur and Larsa. A bronze statue in the Louvre is dedicated by Kudur-mabug and Rim-aku, the father referring to himself as Lord of Yamutbul, a district which is now known from Elam. When, subsequently, Hammurabi attacked Rim-aku, he himself was a king right enough, but in an inferior position, being under the suzerainty of the Elamite emperor. Hammurabi was a native of Babylonia, whereas Rim-aku was an Elamite Kudurid and therefore a foreigner -- and much less acceptable to the native Babylonians. The circumstance which led Hammurabi to rebel and go to war with a superior was probably the humiliation of this Elamite dynasty by Abraham. The assumption is made by many scholars, including George Smith and A. H. Sayce, that Rim-aku and Eri-aku are one and the same person. The grounds for saying this, apart from the fact that it seems the simplest way to explain the situation since both names are identified as "son of Kudur-mabug" and "king of Larsa", are a little complicated and revolve around the fact that in cuneiform the spelling is phonetic. 22. One of these tablets is given in transcript and translated by Boscawen (ref.4), a translation of the other is given by T. G. Pinches, The Old Testament in the Light of Historical Records and Legends of Assyria and Babylonia, S.P.C.K., London, 1908, p.219.

23. T. G. Pinches discusses this in some detail from pp.216ff. in his work mentioned in ref.22. He suggests in his article on Eri-aku (ISBE, vol.2, p.970) that the dual form Rimaku vs. Eriaku could be a kind of bilingualism in view of the Sumero-Babylonian nature of his domains. Boscawen (ref.4, p.102) observes that many of the Chaldean kings assumed dual forms for their names for this reason, including Hammurabi.

24. See T. G. Pinches, "Certain Inscriptions and Records Referring to Babylonia and Elam and their Rulers and other Matters," Transactions of the Victorian Instute, vol.29, 1895, p.72, for a transcription and translation of this notice.  pg.15 of 27 pg.15 of 27

Oversimplifying the situation, it may be said that Rim-aku can be spelled out as Ri-(im)-aku or Eri-aku. (25) In either case the meaning is the same, namely, "servant of Aku".

Summing up this situation, then, we have an individual who is king of Larsa and part and parcel of the Elamite dynasty of which Kudur-lagomer (Chedor-laomer) was paramount, taking part in the campaign in the time of Hammurabi, in which the Elamite dynasty suffered a defeat from which they never recovered. This provided Hammurabi with his opportunity for successful rebellion. As we shall see, the Amraphel of

Genesis 14:1 is almost certainly this same Hammurabi.

The name "Tidal," which appears in the Hebrew as Tidgal and in the inscriptions as Tud-khula, has also been found. (26) He is spoken of as "king of the Goiim," translated as "nations". There is some evidence that by the "Land of Goiim" is intended the "Land of Guti" or "Gutium" of the inscriptions, the district of South Kurdistan along the Median frontier. (27) I have no authority for the following observation, but it interests me that in the direction of Kurdistan lay one fragment of the Indo-European family, that section from which originated the Medes and Persians. In Genesis 10, which precedes this statement by only a little more than three chapters, the children of Japheth (i.e., the Indo-Europeans) are listed briefly concluding with this comment, "by these were the isles of the Gentiles divided" (Genesis 10:5). The word translated here "Gentiles" is the word Goiim, and although the word may properly be translated "nations" without further identification, I think a study of Scripture lends some support to the view that it became in a special way a cognomen for Indo-Europeans generally. (28) This may be true, in fact, even in the New Testament (Luke 21:24, for example). At any rate, we have here an individual mentioned who is said to have been king of the Gentiles who may, therefore, have actually been an Indo-European monarch in which case the sovereignty of Elam was even wider than is commonly supposed. 25. T. G. Pinches, quoting Lenormant, Textes Inedits 70: see Pinches' work mentioned in ref.22, p.216. Fritz Hommel in Ancient Hebrew Traditions (S.P.C.K., London, 1897, p.170) shows that the Sumerian form irim, rim, iri, or even ri mean "servant," so that Eri-aku or Rim-aku would have the same meaning in any case, i.e., "servant of Aku." Rene Labat, Manuel D'Epigraphie Akkadienne (Paris, 1952, p.59) gives the sign  a value of either r or eri. a value of either r or eri.

26. Duncan, J. Garrow, The Accuracy of the Old Testament, S.P.C.K., London, 1930, p.63.

27. Schrader, Eberhard, ref.17, p.123.

28. Since writing this, I have noticed that several inscriptions refer to people associated under Tidal and Chedorlaomer's campaign as the Mandu Tribes or the Umman-Mandu. See Friz Hommel, ref.25, p.183, and T. G. Pinches, ref.24, pp.61, 65. The Manda Tribes were probably Aryan tribes, possibly Scythians, according to W. St. Clair Tisdale in his article on the Medes in Murray's Bible Dictionary, Murray, London, 1908, p.525.  pg.16 of 27 pg.16 of 27

And what of Amraphel? With the recovery of the Code of Hammurabi and a number of inscriptions giving some information about his deeds and the time in which he ruled in Babylonia, scholars who were sympathetic toward Scripture quickly sought to identify him with this Amraphel.

However, it was recognized from the beginning that a direct transliteration from the Babylonian form Khammurabi to the Hebrew form Amraphel was not feasible.

According to Hommel, (29) one solution may be found in the discovery that the second element -rabi was set forth as an ideogram which had an alternative reading or value of -rapaltu. Thus the form Khammu-rabi could equally well have been read as Khammurapaltu, and the alternative form would quite properly be transliterated as Amraphel.

Hommel stated that the terminal -rapaltu is actually found in one bilingual text of Hammurabi's. (30) He observes that the element -rabi which occurs in a number of seemingly genuine Babylonian names of the very same period was nevertheless replaced by the terminal form, -rapaltu. He suggests that this was done for euphonic reasons.

There are certain other explanations of how Hammurabi could be represented by Amraphel, one of which is suggested by Pinches, (31) who thinks that it could have arisen as a result of the deification of the king (while he was still alive), turning the simple form of his name into the compound form, Hammarabi-ilu, where -ilu means "god". Skinner (32) states that Schrader had actually found the form suggested by Pinches. However, there is some doubt among evangelical scholars today about the advisability of identifying Hammurabi with the Amraphel of Genesis 14, since there may be serious chronological difficulties. We do know that Hammurabi subsequently extended his domain to include Palestine and consequently referred to himself as Lugal-Martu, meaning "Lord of the Ammurru (i.e., Palestine)". But the true identity of Amraphel, king of Shinar, cannot be said to have been established yet. Nevertheless, we do seem to have archaeological evidence of three of the 29. Hommel, Fritz, ref. 25, pp.107, 193. The author observes that it was only in the time of the Hammurabi dynasty that the substitute ending of rapaltu is found for rabi, both words being derivatives of a root verb meaning "to be large". It should also be noted that the ideograph for the sound pil is also given a value bi (Labat, ref.25, p.111, sign list no.173) so that Ammu-rapil(tu) could have been pronounced as "Ammu-rabe".

30. Hommel, Fritz, ref.25, p.106.

31. Pinches, T. G., ref.22, p.211.

32. Skinner, John, A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on Genesis, in The International Critical Commentary, Clark, Edinburgh, 1951, p.257.  pg.17 of 27 pg.17 of 27

invading monarchs whose names are given in the biblical account. The whole atmosphere of the incident is clearly consonant with archaeological evidence regarding both the kinds of names common to that era and the kinds of local attachments and spheres of influence existing at that time.

We should not close this survey of kingly names, however, without making some reference to what are sometimes referred to as the Spartoli Tablets. These tablets were first translated and reported upon by Pinches. (33) They were found in a very mutilated form, two of them being entirely unbaked and one baked possibly in recent times by the Arabs who found them. In spite of their incompleteness, considerable portions of the text of each could be translated. When this was done, to the surprise and delight of Pinches, there appeared the names (in their original form) of Chedorlaomer, Arioch, and Tidal. Besides these names were details which seemed to refer to the events which transpired in Babylonia when the Elamites established their sovereignty over the country. Included in this information is the observation that Chedorlaomer had hired mercenaries under Tidal who were neither Elamites nor Babylonians but were referred to as the Umman-Mandu. The Mandu appear not infrequently in cuneiform texts, and they have been identified variously as the Medes or, by Sayce as the Scythians, (34) but virtually always as Indo-Aryans. This would seem to bear out the suggestion which was made earlier that the Goiim were indeed Indo-Europeans. It is also most remarkable to find a tablet with the names of three of the kings.

So confirmatory of Scripture were these tablets that the Higher Critics jumped on them and did everything in their power to deliberately suppress the significance of them. They pointed out that they were so mutilated as to be worthless, that they were cast in a literary form which suggested poetry rather than history, that they were dated very late (Driver suggested 300 B.C. (35)) , and that there were many phrases which were almost unintelligible even where the signs themselves were clear enough, and finally that the names of the kings were sometimes miss-spelled! 33. Pinches, T. G., ref.24, pp.45-65 for transcription and translation of Spartoli III, 2: Spartol; II, 987: Spartoli I, 58; and Spartoli II, 962. Spartoli III, 2 appears to contain the names of Rudbula (Tidal), of Eri-aku's son, Durmah-ilani, and Kudur-lahmil (Chedorlaomer).

34. Sayce, A. H., The Higher Criticism and the Verdict of the Monuments, S.P.C.K., London, 1895, p.45f. Sayce observes (p.126) that it was the combination of the Manda and Mada (or Medes) which led to the emergence of the Medo-Persian Empire under Cyrus.

35. Driver, S. R., The Book of Genesis, in Westminister Commentaries, Methuen, London, 1904, p.157.  pg.18 of 27 pg.18 of 27

When Dr. Pinches first presented his translation, he was very careful to point out all these facts. Having done this, he stated plainly that in the nature of the case, one could not hope to prove anything in the scientific sense but that the three names in a single context accompanied by a state of affairs which fitted in with all that we know of the events of the time could hardly be a coincidence. The Expository Times, (36) one of the "scholarly" papers which echoed the thoughts of the Higher Critics, picked up Pinches' words, quoting them verbatim only just so far as to report his confession that one could not hope to prove anything . . . and there they left it! Such dishonest reporting, while preventing the discovery from being fairly presented to the Christian public, demonstrated a most unscholarly attitude on the part of the critics. It provoked from Dr. Pinches, who was the mildest and most scholarly of men, the only remark which has ever been noted in any of his voluminous writings that suggested the slightest tinge of anger. Even today, not too many references are made to these tablets, although a complete transcription was given by Pinches in a paper presented before the Victoria Institute in London.

Whatever may be said about the Spartoli Tablets, the biblical account is far from mythical. In fact, because of the complexity of the situation at the time and its being a period of transition in which the sovereignty was shifting into Babylonian hands, it seems likely that only a contemporary would have been able to set forth all the details involved with such exactitude and dramatic skill.

Genesis 14 closes with an exceedingly brief record of the encounter of Abraham with Melchisedec. Taken with Hebrews 7:3, where it is stated that the latter was "without father and without mother", we have the sum total of our knowledge of Melchisedec. Yet somehow he has stirred the imagination of Christian people because it appears that such a great man as Abraham, flushed with a recent decisive victory over apparently an invincible enemy, acknowledged him as a superior.

It seems somehow improper to be searching for archaeological evidence regarding Melchisedec, since to many people he appears almost as a supernatural figure. Perhaps he was a supernatural figure. However, even this incident has possibly received some light from archaeology, and it seems proper to set it down for what it is worth. 36. On this, for a full report see John Urquhart, The New Biblical Guide, Marshall, London, no date, vol.2, pp. 9~203.  pg.19 of 27 pg.19 of 27

To begin with, the word Jerusalem appears to be a Hebraized form of a compound name, Uru-Salim. The first element in this compound is a Sumerian word meaning city. The second element is a Semitic word meaning peace. Jerusalem is therefore taken to mean "city of peace".

At one time it was supposed that Salim might have been the name of a deity rather than the word for "peace", so that the original name was entirely Canaanite or Sumerian and simply meant "city of the god Salim." The assumption here is that the name Salim is only accidentally like the Hebrew word Shalom and in itself did not originally have the meaning of peace. However, the evidence for such a deity has not been positively demonstrated. The idea is not held any longer.

In the Tell-el-Amarna Tablets are several letters from a king of Salim whose name appears as Abdi-Taba. This has been interpreted as equivalent to a Hebrew form Ebed-Tob meaning (if some liberties are allowed), "the servant of the Good One", i.e., God (?). The interesting thing about these particular letters which were (and may still be) in Berlin is that the phrase "neither my father nor my mother" occurs in three of them. The king says, "Behold, this land of Jerusalem neither my father nor my mother gave [it] to me -- the arm of the Mighty King gave it to me." This phrase is repeated three times. There is some disagreement about its meaning, which naturally hinges to a large extent upon how one identifies the Mighty King. Pinches believes that it is simply a case of "apple-polishing", the writer being a vassal of the Egyptian pharaoh at the time. (37) Others, such as Sayce, believe it may very well be a reference to God, the Almighty King. At any rate it is remarkable that this turn of phrase should appear in letters coming from a king of Jerusalem to appear once again in Hebrews 7:3 well over a thousand years later. The city under the simpler name "Salim" is mentioned as one of the cities of southern Palestine captured by Ramses II as indicated on the walls of the Ramesseum at Thebes. It is mentioned also by Ramses III by the same shortened name.

This does not throw very much light on who Melchisedec was -- and perhaps we should not expect it. But the circumstances are rather curious.

Insofar as the story of Abraham's tribute to Melchisedec is concerned, it might be pointed out that there is an almost universal custom in societies which are not necessarily primitive but have maintained older traditions 37. Pinches, T. G., ref 22, pp.233-34, for a discussion of this.  pg.20 of 27 pg.20 of 27

unbroken, that in passing through a man's territory it is always customary to send a present to the lord or chief. Abraham passed through territory which evidently was under the jurisdiction of the king of Jerusalem. We have evidence of this from the fact that the Ebed-Tob, whom we have already mentioned, describes himself as having repaired the roads on the very plain in which Sodom and Gomorrah stood. (38) His dominion and responsibility extended at least this far.

Anyone who has read David Livingston's Journals will know how frequently and carefully he observed this custom, which was in no sense a mark of inferiority but a courtesy to the man whose territory it was safe to journey through. Moreover, certain rules existed in different areas with respect to what should be given as a proper present. For example, if an elephant was killed, that part of the elephant which was wounded belonged to the paramount chief in whose territory it was found. Sometimes some more valuable part was demanded, such as one tusk for example, even when several elephants were killed. So long as this was done, the traveller was received with respect and guaranteed safe conduct, being under the protection of the chief. Livingstone never once failed to recognize this custom, a fact which very largely accounts for his safe conduct back and forth across Africa, even when neighboring chiefs were at war with one another.

It may be disappointing to some readers to think that we should propose what has hitherto been taken almost as an act of worship should really have been a mark of courtesy only. However, this much may be said in defense of this view, namely, that Melchisedec is at least absolved from behaving, as some critics suggested, as a man who demanded his share of the spoils without having taken any risks in the conflict. Let me affirm once again, however, that I do not believe any of these things really explain the significance of Melchisedec. The New Testament makes it clear that he did actually in some way stand in God's stead, thus transcending the ordinary events of history. There would have been no need for Scripture to reveal these things about Melchisedec if archaeology could have supplied all the details. 38. See on this a quotation from Sayce by Urquhart in his New Biblical Guide, ref.36, p.214. Elsewhere Sayce points out that this same Ebed-tob worshipped a god named Salim according to a rather mutilated tablet which he "translated" with Winckler (see The Higher Criticism and the Verdict of the Monuments, ref.34, p.176). It should be borne in mind, however, that this Ebed-tob was not Melchisedec, for he appealed to his Egyptian overlord (Sayce, ref.34, p.175) for help against the Habiru and therefore is much later. But the associations of "phraseology," etc., in this incident are interesting.  pg.21 of 27 pg.21 of 27

There follows an incident in the life of Abraham which sometimes leaves one with the feeling that he was not as great-hearted a man as we like to believe. This incident is recorded in Genesis 16:2-4. And Sarai said unto Abram, Behold now, the Lord hath restrained me from bearing; I pray thee go in unto my maid; it may be that I may obtain children by her. And Abram hearkened upon the voice of Sarai. And Sarai . . . gave Hagar her maid to her husband to be his wife. And he went in unto Hagar and she conceived, and when she saw that she had conceived, her mistress was despised in her eyes.

Strictly speaking, archaeology does not shed any light upon this incident, but the study by anthropologists of the ways of contemporary primitive people has done so. Moreover, recent research into the behaviou r of "infants" (whether animals or humans) in the way in which they become attached to "parents" has also shed light on the incident. It is termed "imprinting."

It has often been observed that people who belong to cultures which do not share Western traditions tend to be unexpectedly practical in dealing with live situations which involve not merely mechanical problems but social ones also. Somehow or other such people have noted and made use of the fact that a newborn creature becomes attached strongly, presumably by instinct, to the first object which it fastens its attention upon, particularly in a time of special need. (39) Such needs as shelter from light, warmth, food, and protection -- and perhaps also caressing -- are all found to be powerful "triggers" in this attachment. It may be a little disappointing to find that what is commonly referred to as the "blood relationship" between a parent and child may have exceedingly little effect (if any at all) in establishing a bond between the child and mother. The order in which these two words occur is important, for it is often the child who initiates this bond.

Now, in most societies other than our own, a childless wife tends to have an inferior status, other things being equal. And in a community which raises flocks or herds, children are of particular importance because of their value as guardians and overseers of the animals; in a hunting or industrial society, this is not nearly so true. 39. An interesting paper which summarizes some of the research work being undertaken on this aspect of child-parent relationship, commonly referred to as "imprinting", appeared in very readable form in the English journal Discovery, February, 1961. A useful though brief bibliography is included. The paper is R. A. Hinde, "The Early Development of the Parent-Child Relationship."  pg.22 of 27 pg.22 of 27

Such a wife, (40) then, was permitted by custom to bring to her husband a woman by whom a child might be born on the understanding that the child was immediately placed upon her knees in such a way that its first vision would be the wife rather than the mother. The actual mother withdrew and the attachment of the child to the adopting mother became secure. It was customary always for the wife, not the husband, to choose the woman who should bear the child, and presumably she would take good care that the true mother did not seek to take advantage of her subsequently. If this should occur, however, the wife was given the social right to have the mother removed from the household entirely. And if, as a result of nursing a foster child, the wife's barrenness came to an end and she bore her own child, that child became the "firstborn" in status. That the adopting mother, herself barren, could nurse a child is borne out from experience in primitive societies, and in fact -- extraordinary though it seems -- there have been cases reported in medical literature of men who have nursed children after premature death of the mother. It is reported by David Livingstone from Africa. (41)

In this particular instance, Hagar behaved quite improperly in terms of her own culture when she assumed a superior attitude toward Sarai. It was Abraham's duty, whatever he may have felt personally about the matter, to put an end to Hagar's presumption. Had he not done so, he would have invited other women in a similar situation to behave in an equally socially improper manner. There is no doubt, in the meantime, that Ishmael, Hagar's child -- and Sarai's "son" -- would have grown up with all the strong attachments of a son for his mother which are to be found in a Jewish home. The practice may seem strange to us, but I am quite sure that the relationship between our own sons and fathers and mothers would often seem equally strange to Abraham.

It should also be observed that a woman hitherto barren may, for reasons not yet understood, become pregnant after the adoption of a child into the family. In fact, Scripture supplies us with what is a case in point, i.e., Genesis 30:1-8, 22-24. I am not suggesting that we should seek to eliminate the miraculous by an appeal to 40. The Code of Laws of Hammurabi (a contemporary of Abraham) makes a somewhat analogous provision. See George Barton's translation in Archaeology and the Bible, American Sunday School Union, Philadelphia, 1933, p.391, section 146, which reads: "If a man ak a pristess and she gives to her husband a maid-servant and she bears children, and afterwards that maid-servant would take rank with her mistress, because she has borne children, her mistress may not sell her for money, but she may reduce her to bondage and count her among the female slaves." The significance of the fact that the woman is listed as a priestess is not clear. Certainly the original reads as rendered.

41. Livingstone, David, ref.15. p.141.  pg.23 of 27 pg.23 of 27

natural science, and therefore this observation is only made as an aside -- for it in no way accounts for the fact that Abraham was (insofar as procreation of children was concerned) already as good as dead, and Sarai already past age (Hebrews 11:11, 12). The birth of Isaac was in a special way the Lord's doing.

The record in Scripture of the circumstances surrounding the destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah is as vivid and dramatic as was the record of Abraham's rescue of Lot from Chedorlaomer. These are both clearly eyewitness accounts. As one reads the story, brief though it is, one has no difficulty whatever in imagining what the event must have been like. What it all looked like to the eye is clearly drawn; the only thing missing is what it must have sounded like, for a geological "explosion" of such a nature must have shaken the earth indeed -- must, in fact, have been almost as devastating an experience as the blowing up of Krakatoa in 1883.

That it was, for all its unusualness, a natural event resulting from a series of coincident circumstances is almost certain. The supernatural element, which really constituted it a judgment from God, was the fact that it was clearly predicted within a matter of minutes insofar as the timing of the explosion was concerned. Yet strangely enough, in spite of the immensity of the event, there is comparatively little evidence for it, archaeologically speaking.

Conflicting reports have been circulated from time to time regarding the site as it now is. Not many years ago, it was pictured as desolate and eerie, with little life and nothing but sulfurous fumes hanging heavily over everything to discourage all living things. More recently, (42) it has been described as a most fruitful district set down in among the hills in a deep, deep valley where even winter temperature is almost ideal -- 75-80 degrees (F) during the day, and 69-65 during the night.

It is apparent from exploration in the area during the past half-century that a measure of recovery took place as the years rolled by so that plant and animal life began slowly to populate it afresh. But in the time of Strabo and Tacitus and Josephus, the area was desolate indeed. In their day the description of the valley in which the Dead Sea lies as a veritable "garden of the Lord" (Genesis 13:10) must have seemed far from the truth. Today, with a little enterprise, the area could readily become, as Kyle put it, (43) a most fruitful region -- capable of

42. Urquhart, John, ref.36, pp.226-27.

43. Kyle, Melvin G., "Ancient Sodom in the Light of Modern Science," Transactions of the Victorian Institute, vol. 59, 1927, p.:224.  pg.24 of 27 pg.24 of 27

supporting luscious grass, wheat, excellent vineyards, beautiful fig orchards, and even a sugar industry. It has taken 2,500 years to wash away the effects of the destruction of these cities of the Plain.

In 1924 an archaeological expedition was carried out under the direction of Melvin G. Kyle, president of Xenia Theological Seminary (U.S.) in co-operation with the School of Oriental Research in Jerusalem with the prime object of locating the sites of Sodom and Gomorrah and if possible some of the other cities which suffered a similar fate.

Kyle states as a basic conclusion of this expedition that "there is now scientific evidence that the civilization which the Bible represents to have been on this plain in the days of Abraham and Lot, and of Sodom and Gomorrah, was actually here." (44) Furthermore, he observes that the silence of Scripture which thereafter makes no reference to any subsequent recovery of this region is amply borne out by the complete absence of archaeological evidence of settlement from 2000 B.C. onward. A campsite was found and some graves, but nothing more until Byzantine times.

Kyle and his co-workers were impressed, however, with the evidence which exists even now of what must have been ample water supplies, springs and free flowing rivulets which would almost certainly have supported and indeed encouraged the establishment of permanent settlements.

As to the destruction itself, Kyle believes the evidence is clear that the great catastrophe did take place exactly as narrated in the Bible. According to Scripture, a rain of fire and brimstone fell from heaven and destroyed the plain and all its inhabitants and rendered the area completely infertile for hundreds of years. The event was exceedingly sudden -- in short, explosive in character. Seen from above as Abraham looked down upon it, it appeared that a vast column of smoke went up to heaven as from a furnace.

It is known now as the result of exploratory work carried out by the Standard Oil Company, among others, that there is oil in this region, and geologists state that where oil and asphalt are found there will also be highly flammable gases. Cognizance is taken in Scripture of the presence of oil by its reference to the slime pits

(Genesis 14:10) -- i.e., in the Hebrew, bitumen. It is quite possible that lightning or some other agency ignited a large pocket of gas which in effect blew up in the valley, and the very large quantities of sulfur and salt found in this area were carried red hot into the heavens so that it quite literally rained fire and brimstone over the 44. Ibid., pp. 221, 223.  pg.25 of 27 pg.25 of 27

whole region. One has only to observe the black smoke issuing from a barrel of tar where roads are under repair to realize how much of a cloud would ascend in the event of a vast area like this being involved in a flaming explosion. Accompanying all this confusion, there may well have been a very great earthquake, for the ruptured strata are plainly visible in the valley and the whole region has been known as one where stresses have accumulated, since the valley lies along the path of a major rupture in the earth's crust which continues far down into Africa.

What was not destroyed by shocks or by fire was destroyed by the acrid fumes that accompany burning asphalt. Lot and his family in flight ran desperately ahead of the advancing wave of destruction and barely escaped with their lives. Lot's wife lingered long enough as she looked back at this scene of frightful destruction in which all their wealth was lost, only to be enveloped by the suffocating gases before she could recover herself. Some of the vast quantities of salt that exist in mountainous forms, even to the present time, must have been carried high into the air; as they fell, her recumbent body was quickly buried and encrusted as a fallen pillar of salt.

In time the water courses were changed, the body of water which had always been there as an inland sea gradually deepened until it spilled over into the Plain or Vale of Siddim to the south, slowly burying and hiding the shame of the cities that had once flourished there. The main sea has always been fairly deep (a thousand feet or more), but its extension to the south is quite shallow, having a depth varying from a few inches to some thirty-five feet. It is still rising, in fact, and in the last forty years or so has increased its depth by about ten to twelve inches, submerging trees and probably what remained of the ruined cities. The strong concentrations of salt have tended to preserve what was submerged; in photographs published in the American Journal of Archaeology, (45) some of these submerged trees are visible. The impression one gets reinforces the knowledge obtained from Scripture that it is an area under judgment.

It seems unlikely now that the actual remains of Sodom and Gomorrah will ever be found unless some vast undertaking in the future should lead to the draining off of some of the accumulated waters, once more exposing to view the Vale of Siddim as it formerly existed. 45. Clapp, Frederick, G., "The Site of Sodom and Gomorrah," American Journal of Archaeology , July-Sept, 1936, p.323-44.  pg.26 of 27 pg.26 of 27

Although the following hardly comes under the heading of archaeology, it is nevertheless a remarkable parallel from an interesting source. In the eighth book of Ovid's Metamorphoses (46) there is an account of the destruction of a rich and populous country supposedly in Phrygia in Asia Minor. Jupiter and Mercury disguise themselves and come down to earth in the form of men. They inquire as to the condition of mankind in the region and discover that the people are so godless and evil in their ways that they consider it improper to allow them to live any longer. The two gods go to the house of a devout couple whose names are given as Philemon and Baucis, his wife. There they spend just the length of time which accords with the time spent by the angels in the house of Lot in Sodom. They announce that the whole region is about to be destroyed because of its wickedness, and they recommend Philemon and Baucis to repair to an adjoining mountain. The gods help them away from the doomed place, and when they are within a bowshot of the summit of the mount, Philemon and Baucis look back and see the whole region sunk in a morass. Whether the story is really related or not it is difficult to say, but it would certainly appear to be.

At any rate, as with all the other scriptural accounts of these early times so far examined, the text here is undoubtedly to be understood in the most literal sense. The events as they occurred are described dramatically but without exaggeration or distortion, exactly as one would expect if the writer were either himself an eyewitness or a contemporary of those who had been present. 46. See The Metamorphoses of Ovid, translated by Mary M. Innes, Penguin Classics, 1961, p.214.

pg.27

of 27 pg.27

of 27  Copyright © 1988 Evelyn White. All rights reserved

Previous Chapter Next

Chapter

Home | Biography

| The Books | Search

| Order Books | Contact

Us

Copyright © 1988 Evelyn White. All rights reserved

Previous Chapter Next

Chapter

Home | Biography

| The Books | Search

| Order Books | Contact

Us

|