|

About the Book

Table of Contents

Part I

Part II

Part III

Part IV

|

Part 1: The Universe: Made for Man?

Chapter 2

The Immensity of God's Handiwork

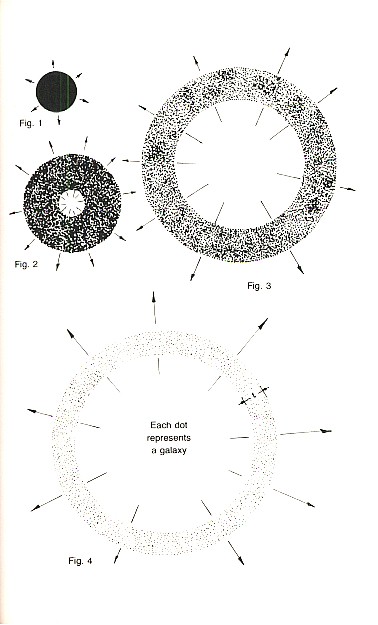

THE PICTURE of the shape of the universe can be elaborated

as a mechanical model by using the analogy of an exploding bomb

referred to by von Weizsacker and considering what must happen

to the fragments which are thus forcibly blown apart. A second

or two after the explosion of a bomb in free space, fragments

will all be flying apart from each other and there will nothing

left of the exploded substance in the center where the bomb first

went off. Under more or less ideal conditions, the fragments

leave this point of origin at approximately the same speed so

viewing the situation in successive moments of time, we observe

something in the nature of an expanding sphere which is entirely

hollow inside, and of which the thickness of the wall representing

the space occupied by the particles of the original bomb fly

outward. The best way to illustrate this process is diagrammatic;

shown on the next page.

In figure 1 we

have the superdense original Uratom. In figure 2 a few seconds

later, expansion has begun. In figure 3 the outward movement

of all the particles leads to the clearance of a space in the

very center which is being left vacant. It should be understood

these diagrams show a cross section of the universe which therefore

may give the false impression that we are dealing with a ring.

In point of fact, we are dealing with an expanding

sphere, not a ring. In figure 4 this "cavity"

is naturally enlarging as the particles fly outward. Meanwhile

the fragments themselves move out with more or less equal force

and speed so that they maintain their position in a comparatively

narrow band and assume the shape of the shell of an expanding

ball which has a very definite thickness (marked t in the diagram

below), the shell itself now being comprised of all the original

matter which

pg.

1 of 7 pg.

1 of 7

pg.

2 of 7 pg.

2 of 7

was in the Uratom before

it began its expansion. Assuming that no more matter is being

created, the expanding shell will do one of two things: it will

become thinner as expansion continues in the same way that

a rubber balloon becomes thinner as it is blown larger, or it

will maintain its thickness as a shell by the simple expedient

of having the particles spaced more and more distantly from each

other so that the material of the universe is attenuated.

As Sir Arthur Eddington put

it: (31)

We can

picture the stars and galaxies as embedded in the surface of

a rubber balloon which is being steadily inflated; so that, apart

from individual motions and the effects of their ordinary gravitational

attraction for one another, celestial objects are becoming farther

and farther apart simply by inflation.

It is important

to bear in mind in this picture of an "expanding universe"

that the universe, strictly speaking, is not some kind giant

space like a box with no top or bottom and with the sides knocked

out. The universe is the film of the expanding balloon.

There is nothing inside of it and, as it continues to expand,

successively takes up its position at a larger diameter where

there was nothing before. It is hard to think of empty space,

and indeed it is probably an entirely incorrect concept; thus

it is not proper to speak of the hollow inside of the balloon

as space at all. Strictly speaking, space is where matter is,

however thinly attenuated. There is space between the orbiting

electrons and the central nucleus of protons and neutrons. There

is space between one atom and the next. There is space between

one solid body of atoms and the next solid body � like two

apples, for example. There is space wherever an area sufficiently

occupied by atoms or by the particles of atoms that anything

in between can be said to be subject to their electromagnetic

influences. Thus space is not the emptiness inside the expanding

balloon, nor is it that into which the expanding balloon is steadily

encroaching by its enlargement outward. Space is strictly the

film of the balloon itself. It therefore has a finite depth which

is the thickness of the shell, but an object can move indefinitely

through it by going round and round.

Thus arises

the concept of a space which is curved. And all the material

in the universe appears to be occupying this comparatively thin

shell--which, however, preserves its shape like the skin of the

inflated balloon, not because there is some kind of air pressure

within it, but because repellent forces between the

31. Eddington, Sir Arthur: quoted by J. W.

N. Sullivan, Limitations of Science, Penguin Books Harmondsworth,

England, 1938, p.27.

pg.

3 of 7 pg.

3 of 7

particles act to hold

them in a kind of negative tension and to drive them further

and further apart, thus causing the whole shell to expand at

an ever-increasing speed. It is apparent that the rate of expansion

is so great even now that galaxies diametrically opposite each

other in this vast shell are already flying apart at speeds approaching

the speed of light.

It seems that ultimately

this giant balloon must either reach a point of equilibrium where

there is no energy left for it to push itself any further �

a condition which would be one of total entropy or, in slightly

different terms, a heat death � or something might happen

to reduce these tremendous forces which drive the galaxies apart

suddenly and dramatically to zero. Then, like a pricked balloon

� or better still, a pricked bubble � the whole gigantic

universe would collapse upon itself and "fold up like a

garment." Indeed, the writer of the

Epistle to the Hebrews tells us that the heavens (which are the

work of His hands) "shall perish . . . and they shall wax

old as does a garment; and as a vesture shall [God] fold them

up, and they shall be changed" (Hebrews 1:10-12).

By all present standards of measurement,

the universe is indeed growing old. If the picture which we have

presented of the universe as being the film of a bubble or the

shell of a balloon is valid, what better descriptive phrase could

one possibly apply to the necessary consequence which would follow

if God suddenly withdrew the energy by which He sustains it all,

than that it would fold up like a garment. How apt this all is!

Scripture is not likely to provide us with scientific information

wherever we can, by our own God-given intelligence, extract it

for ourselves. But whenever we have completed our extraction

and arrived at some fairly secure conclusion, it is amazing how

frequently we discover that the Word of God anticipated our findings

and got there first with a quite explicit and completely appropriate

statement!

Now, the nature

of light is still not precisely understood and can be best accounted

for in contradictory terms by saying that in some ways it behaves

as though it were a wave phenomenon and in other ways as though

it were a particle phenomenon, the particles being called photons.

As far back as 1873 Maxwell had shown that light radiation would

exert a pressure on any surface upon which it fell. (32) Subsequently, it was shown

that a target "flinched" under the impact of radiation

from a bright light just as though a bullet had been fired into

it. It is also found that a photographic plate exposed to light

increases its weight as though something had landed upon it.

All these phenomena suggest that light has some kind of mass.

What kind of

32. Maxwell: see Sir James Jeans, The Mysterious

Universe, Cambridge University Press, 1931, p.55.

pg.

4 of 7 pg.

4 of 7

mass is involved is hard

to conceive, but it does appear subject to magnetic forces, for

it is bent in the presence of a magnetic field. If the magnetic

field through which the beam of light is passing is curved in

the way that space of the Universe which we have been considering

is curved, then a beam of light will not travel "straight"

but will follow the curve like a train following a long slow

curve predetermined for it by the railway tracks.

Thus light reaching

us from some of the distant galaxies does not reach us by striking

across the balloon by way of a short-cut but is channelled round

the shell itself. Indeed, according to Eddington, (33) some of

the nebulae that we see in the heavens which are at tremendous

distances from us, millions of light-years away, may possibly

be so far around in the curvature of space that their light is

reaching us from the other side and we are actually seeing the

back of them. This possibility had led to the perfectly sane

observation that if we looked in exactly the right direction

and could see far enough, we should see the back of our own head!

In point of fact, however this is quite impossible because

the circumference of this whole universe is so great that millions

of years before the light reflected from the back of our head

could travel all the way around until it finally reached our

eyes, we should long since have disappeared from the scene.

The scale of magnitude

involved here is inconceivably great. Ordinary terms of measurement � feet

and yards and miles � become totally inadequate,

and we have to fall back upon the use of a scale involving light-years.

A light-year is the distance which light would travel in one

year while moving at a speed of 186,000 miles per second. It

works out at a distance of approximately 6,000,000,000,000 miles.

Some of the distant galaxies are believed to be millions of light-years

away � not millions of miles merely, millions of

light-years! Moreover, the universe has already expanded to such

a size and the distances have become so great that probably the

greater part of it has long since passed beyond our observational

powers. The light from these most distant galaxies simply will

never reach us.

Matching these

inconceivable distances are inconceivable quantities of material.

As George K. Schweitzer said: (34)

Our sun is one of about 100,000,000

000 stars which make up a giant community of stars known as a

galaxy....

Our galaxy is a member of a small

cluster of 19 galaxies. They occupy a region over 3 million light-years

in diameter. Nearest in space to our cluster are a few other

galaxial clusters. The first large cluster is about

- 33. Eddington, Sir Arthur: quoted by J. W.

N. Sullivan, Limitations of Science,Penguin Books, Harmondsworth,

England, 1938, p.27.

34. Schweitzer, George K., "The Origin of the Universe"

in Evolution and Christian Thought Today, edited by Russell

Mixter, Eerdman's, Grand Rapids, Michigan, 1959, p.36.

pg.

5 of 7 pg.

5 of 7

30 million light-years from us, and it

contains over 1000 galaxies. On and on out into space in all

directions cluster after cluster can be seen, as far out as telescopes

can reach. Over a billion galaxies can now be observed. (This

gives a total of 100,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 stars, or 100

sextillion stars).

And in this

vast immensity of space and substance, our little sun is therefore

but a tiny fragment, and our little world an even more minute

particle. Can such a particle have any significance?

It is a curious

thing that man should find a peculiar delight in minimizing his

own significance in the universe. He seems to find an odd satisfaction

in underscoring the hugeness of everything by contrast with his

own mere 160 pounds, and the enormous time-scale by contrast

with his own three score and ten years. So thoroughly has the

philosophy of materialism impregnated our thinking that we have

come to measure ourselves and our personal worth in quantitative

terms, in terms of years and pounds! No wonder our insignificance

strikes us so forcibly. A few years ago, J. W. N. Sullivan put

it this way: (35)

The vast extent of the Universe,

both in space and time, is, from the human point of view, completely

aimless. Those immense lumps of matter, in their millions of

millions, incessantly pouring out an inconceivably furious energy

for millions and millions of years, seem to be completely pointless.

For a fleeting moment man has been permitted to stare at this

gigantic and meaningless display.

Long before the process comes to

an end, man will have vanished from the scene, and the rest of

the performance will take place in the unthinkable night of the

absence of all consciousness.

- But just suppose

our value is not to be measured quantitatively at all. With very

few exceptions--and Bertrand Russell is a notable one--men have

always recognized that it is quality and not quantity which gives

stature to the individual. Even the making of this judgment itself

is evidence of a capacity in man which cannot be accounted for

in any of the terms by which we measure the immensity of the

universe. Indeed, if we were merely part of the universe in the

sense that animals are part of it, or plants or rock formations

or even molecules, we should never have troubled ourselves with

searching out its immensities in the first place. Those who loudly

proclaim that man is an insignificant by-product are, by their

very proclamation, bearing a tacit witness to the fact that they

themselves are not a product of it at all, but are standing outside

of it and making a judgment about it. There is no question that

Scripture in a thousand ways singles out the individual as being

-

- 35. Sullivan, J.W.N., Limitations of Science,

Penguin Books, Harmondsworth, England, 1938, p.33.

pg.

6 of 7 pg.

6 of 7

something other than, more valuable than, and of vastly greater significance

to God himself than the mere chemicals of which his body and

even his brain are composed. He may look up at these tremendous

galaxies and wonder at his own tiny size. But he has this advantage:

galaxies don't know that he is down here, but he knows they are

up there.

The question arises,

then, whether such a creature could have been created as part

of some other kind of Universe, a Universe in keeping with his

physical dimensions and his span of years. Is this tremendous

display of power unnecessarily wasteful--one might almost say,

flamboyant? Certainly, we have no reason now, in the light of

what we know, to doubt the power of the Creator. But what about

His wisdom? Could man have been introduced into a more modest

cosmos in terms of size and age? I think the answer to this is

not difficult. God has infinite resources and there must be other

alternatives that He might have chosen. But evidently He had

a reason for creating such a universe, and since reasonableness

is a concept which only has meaning in terms of man's thinking

processes, we ought to be able to follow God's thinking to some

extent and to grasp something of the rationale of His adopting

such a plan.

pg.

7 of 7 pg.

7 of 7  Copyright © 1988 Evelyn White. All rights

reserved

Previous Chapter Next Chapter

Copyright © 1988 Evelyn White. All rights

reserved

Previous Chapter Next Chapter

|