|

Abstract

Table

of Contents

Part I

Part II

Part III

Part IV

Appendixes

|

Part I: The Intrusion of Death

Chapter 10

Towards The Identity

Of The Forbidden Fruit:

(1) According To Tradition

Hast thou eaten of the

tree,

whereof I commanded thee that

thou shouldest not eat?

(Genesis 3:11)

In the sweat of thy face

shalt thou eat bread,

till thou return unto the ground;

for out of it wast thou taken:

for dust thou art,

and unto dust shalt thou return.

(Genesis 3:19)

I do not really

think that we shall ever be allowed to identify the poison with

any certainty, for that would be to invite a search for an antidote.

With our present sophisticated techniques of investigation, we

might succeed! And my feeling is that the Lord would never allow

such a thing to happen, because the consequences for man would

be much the same as having allowed access to the Tree of Life

which in the circumstances would have been worse than death.

Our minds being what they are,

however, it is difficult not to find ourselves wondering whether

a single poison really could be responsible for the sorry plight

in which man now finds himself both physically and spiritually,

and whether such a poison could be derived from the mere eating

of some particular fruit that

pg.1

of 14 pg.1

of 14

was: (1) good for food,

(2) pleasant in appearance, (3) in some way desirable to make

one wise (possibly enhancing perception), as Genesis 3:6 tells

us.

I think it is not altogether impossible

that the royal physician to Henry II of France, Dr. Jean Fernel,

was correct in his belief that if the plants and herbs of the

world were examined with sufficient thoroughness, we would find

a remedy "for each and every human illness that exists."

(134) Whether he

really meant that some single remedy would ultimately be found

for all sicknesses alike is not clear, but I have the impression

that this was in the back of his mind. A single cure implies

a single cause at the first.

Nearly a century ago, J. Cynddylan

Jones suggested that "in the leaves of the Tree of Life

was medicine for all forms of sickness." * He said, "Today,

healing virtues are distributed in hundreds of plants, specific

plants being remedies for specific diseases; but in the Tree

of Life were probably concentrated the medicinal virtues of all

the vegetable creation, and special virtues of its own in addition,

and thus it was a universal panacea against all the evils of

sickness."

Even now we have

some remedies (aspirin, for example) that have an extraordinarily

wide application against all kinds of ills, which therefore certainly

demonstrate that a single substance can be effective against

a very broad range of common human ailments. Thus, it is not

so entirely unreasonable to assume that at the very root of all

human sickness there might lie some single basic defect in the

body responsible for all other ills. If ever some plant extract

should be found which could supply the single antidote, we should

probably find, in effect, that we had discovered the identity

of the Tree of Life.

It will be well to set forth the

characteristics that the poison in this fruit must have had in

order to cause the effects which Genesis seems to indicate it

did. These are as follows:

(a) It must be a protoplasmic

poison, a poison that ultimately causes the death of cells, and

therefore the death of the body.

(b) It must have a more immediate short range

effect, such that a perceptive individual would very quickly

observe its effects in others or in himself. It might be expected

that the effect would in some way heighten awareness of one's

own body.

(c) It must be obtainable from a fruit that

is otherwise good for food and pleasant to look at.

(d) It must produce an effect that is inheritable.

If I am interpreting the

134. Sherrington, Sir Charles, Man On His

Nature Cambridge University Press, 1963, p.33, 34.

* Jones, J. C., PrimevaI Revelation: Studies in Genesis 1-VIII,

London, Hodder & Stoughton, 1897, p.210.

pg

2 of 14 pg

2 of 14

circumstances in Genesis

correctly, the inheritable effect should be male sex-linked.

(e) It must have a detrimental effect not merely

on the body but also on behaviour, contributing as a consequence

to man's moral, not simply to his physical, deterioration.

(f) It must be potent in very small quantities,

and ought to be capable of being neutralized in its physical

effects but not in its moral effects, by some plant extract such

as might have been derived from the Tree of Life.

There are two

other considerations which it ought to satisfy. We should expect

to find shadowy recollections of its characteristics reflected

in the traditions of antiquity. And we should expect to find

intimations of its identity in other parts of Scripture.

Having set forth these specifications,

it may occur at once to a thoughtful reader that alcohol satisfies

the requirements. It is very tempting to make this equation.

Tradition, what we know of the etiology of alcoholism, and the

intimations in Scripture, all combine to reinforce this conclusion.

Yet, personally, I doubt whether it was actually alcohol, at

least not the common ethyl alcohol. Perhaps it was one of the

higher alcohols which are far more potent. But I do believe that

alcohol provides the most complete paradigm of the poison

of which we currently have knowledge, and I believe that grapes

as the source of the poison provide the best paradigm of the

forbidden fruit.

It is important to underscore the

fact that a paradigm is not to be taken as the thing itself but

only as a useful parallel. I want to emphasize this, because

I have some doubts whether grapes or their by-product (ethyl

alcohol) as we now know them, are precisely to be equated with

the forbidden fruit or with the poison it was capable of generating.

My reasons for saying this are chiefly that I have not yet been

able to satisfy myself completely about certain statements in

Scripture which it seems to me could hardly have been made (approving

the use of wine and of grapes) if the latter really were the

original forbidden fruit which has caused all our ills.

The most serious of errors often

arise by assuming as identical, things which merely correspond

in obvious ways. The more nearly things are similar without being

identical, the greater may be the danger of equating them. The

more nearly a lie approaches the truth, the more dangerous it

can be. So I should like to repeat that I do not yet believe

that grapes, as we now have them, were the forbidden fruit or

that alcohol was really the poison which introduced death to

the human race � though I believe they may come remarkably

close to it.

Thus we can usefully discuss the

reality of that crucial event with some such fruit or by-product

as a model, because it is close enough in

pg.3

of 14 pg.3

of 14

many remarkable ways

to assist our imagination, and it assuredly demonstrates that

such a situation could indeed have existed with precisely the

consequences to Adam and to Eve and to their descendants which

the Genesis record clearly indicates.

Having due regard, then, to the

above cautionary observations, consider first the following gleanings

from the literature of antiquity both pagan and Jewish; and then

(in Chapter 11) some observations regarding what is known about

alcohol and the etiology of alcoholism as a disease. Following

this (in Chapter 12), we will examine certain intimations in

Scripture which are interestingly illuminated if we assume that

the fatal poison shared many of the characteristics of alcohol

in its effect on both the body and the spirit of man.

Many of the

nations of antiquity have traditions of the Fall of man and relate

the event in one way or another to the eating of a food or the

drinking of a fruit extract. These traditions sometimes confuse

the circumstances by assuming that what the tempter said was

actually true; that the Tree of Knowledge was a tree whose fruit

brought not only benefit to the eater in the form of a superior

kind of wisdom (which in a sense it did) but also a higher

kind of life (immortality like that of the gods). (135) Sometimes they state

categorically that the offending substance was the juice of a

fruit or an extract like the sap from a tree, and that it poisoned

the body. Some of them clearly indicate that the result was inebriation,

but they attach to this a kind of benefit in that the individual

then transcends the ordinary limitations of human experience

and enters into special communion with the gods. In some cases

the plant or tree is identified by name, though the precise nomenclature

of the original is not always clear in modern terminology.

The earliest of such non-biblical

traditions are to be found among the Cuneiform tablets of Sumeria

and Babylonia. Here are some extracts from such early records

as reported in the literature at the time when they were first

found. It is necessary to say this because later collections

of Cuneiform inscriptions do not always translate these same

tablets in precisely the same way, and in some cases the names

of the deities have been spelled differently. In 1895 Dr. T.

G. Pinches, one of the earliest notable Cuneiform scholars in

England, reported the finding of a tablet which begins thus:

*

In Eridu grew a dark vine

In a glorious place it was brought forth.

134. See in Notes at the end of this chapter

(p.14).

* Pinches, T. G. "On certain Inscriptions and Records Referring

to Babylonia and Elam," Transactions of the Victoria

Institute, London, vol.29, 1895, p.44.

pg.4

of 14 pg.4

of 14

This

is not very much to go on, but the tablet as a whole is clearly

a reference to the beginnings of human history. The "glorious

place" seems obviously to refer to the Garden of Eden. The

problem here, however, is to decide whether this dark tree �

perhaps the word shady might be equally appropriate �

was the Tree of Knowledge which was forbidden before the

Fall or the Tree of Life which was forbidden after the

Fall. The tablet does not state whether the tree was forbidden

� only that it was there; and therefore we really have no

clue as to which of the two trees the writer had in mind: only

that it was a vine.

The following year, W. St. Chad

Boscawen published a translation of a fragment of a tablet which

reads as follows: *

(1) The great gods, all of them determiners of Fate,

(2) Entered, and death-like the god Sar filled.

(3) In sin one with the other in compact joins.

(4) The command was established in the Garden of the god.

(5) The asnan fruit they ate, they broke in two:

(6) Its stalk they destroyed;

(7) The sweet juice which injures the body.

(8) Great is their sin. Themselves they exalted

(9) To Merodach, their redeemer, he appointed their fate.

As rendered

by Boscawen, himself no mean Cuneiform scholar, the picture seems

clearly to reflect the circumstances of the Fall and to connect

it with an act of disobedience which was viewed as a great sin.

I had considerable difficulty in tracking down the source of

this excerpt from the Cuneiform literature, chiefly because �

when I did finally find it � modern renderings are substantially

different. This is actually a translation of the last nine lines

of Tablet III of an Akkadian creation tablet. The same passage

(1.130-139) as translated by E. A. Speiser reads as follows:**

(1) All the great gods who decree the fates

(2) They entered before Anshar, filling (Ubshukirma)

(3) They kissed one another in the Assembly

(4) They held converse as they (sat down) to the banquet

(5) They ate festive bread, poured (the wine)

* Boscawen, W. St. Chad, The Bible and

the Monuments, London, Eyre and Spottiswoode, 1896, p.89.

** Speiser, E. A., "Akkadian Myths and Epics" in Ancient

Near Eastern Texts, edited by James B. Pritchard, Princeton,

1969, p.65, 66.

pg.5

of 14 pg.5

of 14

(6) They wetted their drinking-tubes

with sweet intoxicant.

(7) As they drank the strong drink, (their) bodies swelled

(8) They became very languid as their spirits rose

(9) For Marduk, their avenger, they fixed the decrees.

It will be seen

that there are marked differences between the two renderings.

We have numbered the lines in order to assist the reader to see

to what extent they match.

It seems important to examine this circumstance

with care for several reasons. First of all, it should be understood

that there are problems even yet in the reading of the Cuneiform

text. The problems arise from the fact that each Cuneiform sign

does not represent a letter of an alphabet which always has the

same sound value, but may have as many as twenty different sound

values. For example, the sign may

be read with the following sound values: UM, UMU, UD, TAM,

PAR, HISH, and some other alternatives. There are certain

guides to indicate to the reader which particular sound value

the sign is carrying in any given circumstance. But these indications

are not always clearly understood even by modern Cuneiform scholars,

and different scholars sometimes adopt different readings for

the same sign. Let me illustrate in completely modern terms what

can be involved in translating a tablet. Let us suppose some

particular sign could be read either as CR1 or HOC,

and this sign in a particular sentence could be followed

by a second sign which is known to have two alternative values

which are KEY and KET. I suspect that if it were

known that the tablet was recording something to do with a game,

an English Cuneiform scholar would almost certainly read it as

CRICKET; whereas a Canadian Cuneiform scholar would almost

certainly read it as HOCKEY. may

be read with the following sound values: UM, UMU, UD, TAM,

PAR, HISH, and some other alternatives. There are certain

guides to indicate to the reader which particular sound value

the sign is carrying in any given circumstance. But these indications

are not always clearly understood even by modern Cuneiform scholars,

and different scholars sometimes adopt different readings for

the same sign. Let me illustrate in completely modern terms what

can be involved in translating a tablet. Let us suppose some

particular sign could be read either as CR1 or HOC,

and this sign in a particular sentence could be followed

by a second sign which is known to have two alternative values

which are KEY and KET. I suspect that if it were

known that the tablet was recording something to do with a game,

an English Cuneiform scholar would almost certainly read it as

CRICKET; whereas a Canadian Cuneiform scholar would almost

certainly read it as HOCKEY.

Any such analogy can be misleading,

but this is the nature of the problem, and when we compare the

renderings of earlier scholars with those of later scholars we

sometimes have an analogous bias, only the bias is not between

English and Canadian sporting interests but between a not unnatural

tendency among earlier scholars to look for reflections of the

biblical story in contrast to the almost total indifference �

indeed, even hostility � towards such a goal among modern

scholars. Looking at the two renderings by Boscawen and Speiser,

one has to admit that Speiser's knowledge of Cuneiform was far

greater than that of his predecessors because he was standing

on their shoulders. On the other hand, it must be admitted that

Boscawen's rendering makes much better sense on the whole.

At any rate, even Speiser's translation,

if we use Boscawen's as a background, does suggest that a beverage

described as a sweet intoxicant with harmful effects both on

body and spirit was involved. And

pg.6

of 14 pg.6

of 14

admittedly, it is not

easy to discern the figures of Adam and Eve since the chief characters

in this little play are said to have been "all the great

gods."

In a most useful little handbook

on Archaeology and the Bible, S. L. Caiger gives a translation

of a small fragment of a Cuneiform tablet, which also seems to

have some bearing on the Fall, though it, too, is far from clear

as to its meaning: *

My King the cassia plant approached;

He plucked, he ate,

Then Ninharsag in the name of Enki

Uttered a curse:

"The face of life, until he dies, shall he not see."

This same extract

is rendered slightly differently by S. N. Kramer, but the import

of the words is essentially the same.†

The identity of the fruit as coming from a cassia plant does

not help us very much. But we do note that the effect was to

exclude the eater from the presence of his god until he has paid

the penalty of death.

We have to conclude, I think, that

the only light at present available to us from the Cuneiform

literature is very indistinct, a rather odd circumstance in view

of the tremendous number of tablets that have been translated.

It is to the pictorial representations of the Fall that we have

to turn in order to find any unequivocal reflection of the Genesis

story.

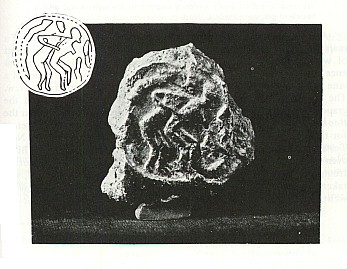

Figure 4. The Seal of Adam and Eve and the Serpent

Figure 4. The Seal of Adam and Eve and the Serpent

An ancient

Babylonian seal, one of many seals that have been discovered

by archaeologists, reproduced in Fig. 4 as a line drawing taken

* Caiger, S. L., Bible and Spade,

Oxford, 1936, p.19.

† Kramer, S. N., From

the Tablets of Sumer, Indian Hills, Colorado, Falcon's Wing

Press, 1956, p.174.

pg.7

of 14 pg.7

of 14

from George Smith's The

Chaldean Account of Genesis (published in 1880), * clearly

shows the temptation scene, with the tree in the centre, an erect

serpent standing presumably behind Eve. The forbidden tree looks

suspiciously like a trained vine with two clusters of grapes.

Adam and Eve are each reaching out a hand towards the fruit.

The shape of the tree itself which tempts one to assume it might

be a vine, may not of course signify anything more than the artist's

sense of symmetry.

In 1932 E. A. Speiser

of the University Museum of Pennsylvania, discovered a seal near

the bottom of the Tepe Gawra Mound twelve miles from Nineveh.

He dated this seal at about 3500 B.C. It is the picture of a

naked man and a naked woman walking as if utterly downcast and

brokenhearted, followed by a serpent. The seal is about one inch

in diameter, engraved on stone, and is now in the University

Museum in Philadelphia. Speiser considers it to be "strongly

suggestive of the Adam and Eve story." It is shown below

in Fig. 5.†

Figure 5.

Figure 5.

* Smith, George, The Chaldean Account of

Genesis, new edition, revised and corrected by A. H. Sayce,

London, Sampson, Manton, Searle & Rivington, 1880, p.88.

† Speiser, E. A., quoted by H. H. Halley, Pocket

Bible Handbook, Chicago, published privately, 19th edition,

1951, p.68.

pg.8

of 14 pg.8

of 14

Even

in the matter of pictorial representations from the earliest

periods we therefore admittedly have little enough to go on.

From later millennia (B.C.) we do seem to have more specific

data. Many years ago, Francois Lenormant reported the finding

of a curiously painted vase of Phoenician manufacture, probably

of the sixth or seventh century B.C. * This had been discovered

in an ancient sepulchre in Cyprus. It exhibits a leafy tree "from

the branches of which hang two large clusters of fruit"

while a great serpent advances with an undulating motion towards

it.

The American

Journal of Archaeology some years ago carried an article

by Nelson Glueck reporting on the general findings in Palestine

and elsewhere during the years of excavation immediately prior

to 1933. He mentions that:†

In one of the two tombs discovered

southwest of the Jewish colony of Hadra, a lead coffin was found.

On one side it is decorated with an arch which rests upon two

twisted columns. Under the arch a naked body holds a serpent

in his right hand and a bunch of grapes in his left.

A coffin seems

a particularly appropriate setting for a picture of a man in

his youth, naked, and holding in either hand the elements out

of which physical death may have found its way into human experience.

The tradition of the forbidden fruit as being the product of

a vine is widespread, though it is not always a grapevine that

is in view. The Jewish people themselves, however, seem to have

favoured the grape as the offending fruit, and this concept is

clearly reflected in the Book of Enoch. The Book of

Enoch has always had a special interest for the Christian

because it is the one book quoted from in the New Testament which

is non-canonical and is not bound with the Bible even when the

Apocrypha is included. The allusions to it are not infrequent

and it is generally held that the title, "the Son of Man,"

was taken from it. In Chapter 32 the writer of the book tells

how he went in search of the Garden of Eden and he says (verses

3 and 4):

And I came to the garden of

righteousness, and I saw the mingled diversity of those trees;

many and large trees are planted there, of goodly fragrance,

large, very beautiful and glorious, also the tree of wisdom;

eating of it one learns great wisdom.

It is like the carob-tree and its

fruit is like the clusters of the vine, very good.

* Lenormant, F., in Contemporary Review,

Sept., 1879, p.155.

† Glueck, Nelson,

"Palestinian and Syrian Archaeology," American Journal

of Archaeology, Jan-Mar., 1933, p.164.

pg.9

of 14 pg.9

of 14

The writer of the book then goes on to tell how he

questioned his angelic guide about this particular tree (verses

5 and 6):

And I said, "This tree

is beautiful. How beautiful and pleasant to look at!"

Then the holy angel Raphael who

was with me, answered and said unto me, "This is the tree

of wisdom from which thy old father and thy aged mother who were

before thee, ate, and they learned wisdom, and their eyes were

opened, and they learned that they were naked, and they were

driven out of the garden."

Paul Isaac Hershon

in his Rabbinical Commentary on Genesis, states that against

Genesis 3:6 and the words "the Tree was good for food,"

there is this rabbinical comment: *

Some of the sages say that it

was a fig tree and that was why they plucked the leaves from

the fig tree to cover their shame; for as soon as they had eaten

of the tree of knowledge their eyes were opened, and they were

ashamed to go about naked.

But some sages say that the tree

was a vine. Eve pressed the grapes and gave Adam red wine to

drink, as red as blood.

The same author,

in another work, in commenting on Genesis 1:27 quoted from the

Talmudic Tractate Sanhedrin (folio 70, col. 1) as follows:†

The Holy One, blessed be He!

said to Noah, Thou shouldest have taken warning from Adam ("the

man of the earth") and not have indulged in the use of wine

as he did. Hence Noah is called (Gen. 9:20) "the man of

the earth." This accords with the Rabbi who maintains that

the forbidden tree was a vine.

According to

Louis Ginsberg in his Legends of the Jews, Origen in commenting

on Genesis 9:20 maintained that Noah's vine was an off-shoot

of the Tree of Knowledge, and Ginsberg observes that the same

view is reflected in the Jerusalem Targum.‡

So far, then, we see various traditional

identifications of the tree. The Cuneiform

* Hershon, Paul Isaac, Commentary

on Genesis, London, Hodder and Stoughton, 1885, p.27

† Hershon, Paul

Isaac, Genesis with a Talmudical Commentary, London, Bagster

and Sons, 1881, p.67.

‡ Ginsberg, Louis, The Legends of the Jews, Philadelphia,

Jewish Publication Association of America, 1955, vol.V,

From Creation to Exodus, p.190, note 59. Dr. Alfred Edersheim,

himself a Hebrew Christian and author of that great classic,

The Life and Times of Jesus the Messiah [London, Longmans,

Green & Co., 1900], in a lesser known work of his, notes

that a number of rabbis held this view (See his The World

Before the Flood, London, Religious Tract Society, no date,

p.55).

pg.10

of 14 pg.10

of 14

records speak of it

as a Cassia plant or an Asnan fruit. The Book of Enoch speaks

of it as a Carob tree. The Talmud favours the grape vine. There

is, of course, the famous apple which some scholars believe arose

from a mistranslation. It happens that in Latin the word for

an evil thing and the word for apple are the same,

malum. The tree of good and of evil in any Latin

rendering may possibly have been rendered by someone as a good

apple tree.

There is another tradition to which

Francois Lenormant refers: *

The most ancient name of Babylon

in the idiom of the first settlers in that region was "the

Place of the Tree of Life," and even on the coffins of enameled

clay of a date later than Alexander the Great, found at Warka

(the ancient Erech of the Bible and the Uruk of the inscriptions)

this Tree appears as the emblem of immortality. Strange to say,

one picture of it on an ancient Assyrian relic has been found

drawn with sufficient accuracy to enable us to recognize it as

the plant known as the Soma Tree by the Aryans of India, and

the Homa of the ancient Persians, the crushed branches of which

yield a draught offered as a libation to the gods as the water

of immortality.

It might be

argued that we have here better evidence to support a theory

that it was the Tree of Life which was a vine rather than the

Tree of Knowledge. But I think that Satan had something to do

with this confusion in tradition, even as he had much to do with

the confusion in Eve's mind. If we are dealing with a fruit capable

of fermentation, it is not surprising that the apparently

heightened prophetic insights which have often been claimed

by priests under the influence of alcohol might soon transform

something that was actually a poison into an ambrosia of the

gods.

The soma or horna tree is generally considered

to be the Asclepias acida, a tree associated in the Vedic

hymns with the god Soma, just as the Asnan fruit may have

been associated with the goddess Ashnan. It was important

in Vedic ceremony, in the words of one encyclopedia, "because

of its alcoholic character . ." In one hymn, those who have

drunk the juice of the plant are said to have exclaimed together,

"We have drunk the soma: we have become immortal: we have

entered the light: we have known the gods!" Such a sequence

reminds us of the assurances given by Satan when he tempted Eve

to take the forbidden fruit.

Dr. Gordon R. Wasson, in an interesting

paper on psycho-active drugs, speaks of the Indo-Aryans and the

Soma as follows: (136)

* Lenormant, Francois, The Beginnings of

History, New York, Scribners, 1891, p. 85, 86.

136. Wasson, Gordon R., "Fly Agaric (Amenita muscaria)

and Man," in Ethnopharmacological Search for Psycho-Active

Drugs, edited by Daniel H. Efron, published by U.S. Department

of Health, Education and Welfare, Public Health Services Publication,

no.1465, 1967, p.413.

pg.11

of 14 pg.11

of 14

An

Indo-European people who call themselves Aryans conquered the

Valley of the Indus in the middle of the second millennium B.C.

Their priests deified a plant which they called Soma, that has

never been identified: scholars have almost despaired of finding

it. The hymns that these priests composed have come down to us

as the Rig Veda, and many of them concern themselves with Soma.

This plant,

Soma, was an hallucinogen. The juice was extracted from it in

the course of the liturgy and forthwith drunk by the priests

who regarded it as a divine inebriant. It could not have been

alcoholic for various reasons: for one thing, fermentation is

a slow process which the Vedic priests could not hurry.

As we shall see, Wasson's last

observation is not entirely justified, for there do exist fruit

extracts which will ferment within a few hours in warm weather.

One wonders whether such fruit juices were not originally drunk

simply because they were sweet and pleasant to the taste, and

that their intoxicating character after fermentation was an accidental

discovery. The undesirable effects of intoxication may have come

as a surprise in view of the original harmlessness and sweetness

of the extract. It may be that this circumstance was responsible

for the belief held by some people that this was really the work

of the devil, turning sweetness into bitterness and corrupting

man's taste. In some parts of the world it is specifically believed

that it was evil spirits who persuaded man to take the first

intoxicating liquor. Dr. S. H. Kellogg gives a tradition from

India which he believes owes nothing to borrowing from Christian

missionaries. His account is as follows: *

The Santals have a tradition

. . . that in the beginning they were not worshippers of demons

as they are now. They say that, very long ago, their first parents

were created by the Living God; and that they worshipped and

served Him at first: and that they were seduced from their allegiance

by an evil spirit Masang Buru, who persuaded them to drink an

intoxicating liquor from the fruit of a certain tree.

On the

whole, there is a certain concordance in this testimony both

from pagan and Jewish sources. In the first place, man's down-fall

was associated with the eating of a fruit. This action brought

with it both a gain and a penalty. In some cases the gain is

a superior kind of wisdom, prophetic wisdom, and in others it

is "knowing the gods," whatever this signifies. On

the other hand, most of the traditions see it as an act of disobedience

which of necessity also involved the penalty death. The Rig Veda,

however, is an exception in

* Kellogg, S. H., Genesis and the Growth

of Religion, London, Macmillan, 1892, p. 60, 61.

pg.12

of 14 pg.12

of 14

this regard, for though

the drink was intoxicating, it also was supposed to have guaranteed

immortality.

In spite of this kind of contradiction,

one has a feeling there is a link between all these accounts

and that they bear witness to the fact that the human race is

truly one and had one father Adam and one mother Eve, a knowledge

of whose early history thus became the common property of all

their descendants, i.e., mankind. The inconsistencies and contradictions

of these traditions may actually strengthen our confidence in

the original account in Genesis in the same way that a certain

type of contradiction in the testimony of several witnesses to

a crime may furnish the best proof that they have not borrowed

their story from one another but are recollecting the original

event without collusion among themselves.

Two facts seem to stand out: the

fruit of some kind of tree was involved and the extract of the

fruit was an intoxicant, a poison; whether it was some form of

alcohol or not is a moot point, but it is a not unreasonable

surmise

pg.13

of 14 pg.13

of 14

NOTES

135. (See p.4) The nations of antiquity often have traditions

that seem to be reflections of the two Trees in the Garden of

Eden, though the role of the two trees is sometimes reversed.

There was in the old world in classical times a very widespread

association in certain festivals between the drinking of an alcoholic

beverage (which might be seen as a recollection of the forbidden

fruit) and the acquisition of immortality (which would seem to

be related rather to the Tree of Life). The ancient gods of Greece

and Rome drank fermented wine (nectar) or ate a food associated

with such wine (ambrosia) to preserve their immortality.

Ambrosia was commonly described

as the "food of the gods," and nectar as the "drink

of the gods." There is no question that both were related

and sometimes the terms were used interchangeably, or reversed

in meaning. The ancient Greek Poetess, Sappho (seventh century

B.C.) and Anaxandridas (d. 520 B.C.) both say that ambrosia was

a drink. Homer refers to it however as like an ointment or an

oil for anointing the bodies of the dead to preserve them from

corruption, whereas he describes nectar as resembling red wine

and states that its continued use brings immortality [Iliad,

XIV, 170; and XIX, 38].

The word ambrosia is held

by some authorities to be of Greek origin, composed of a

(not) and brotos (mortal), i.e., not mortal, immortal.

Liddell and Scott suggest an etymological connection with the

Latin root MORT-.

Homer also refers to ambrosia as

being an unguent for the treating of wounds, an observation again

reflected in the widespread use of fermented wine in the same

connection. This practice is observed in Luke 10:34, where the

good Samaritan treated the severely wounded man that he found

beside the road on his way to Jericho by "pouring oil and

wine" into his wounds.

Ambrosia was a central element

in several Festivals observed in Greece (and elsewhere) in connection

with Dionysus, "the god of peasants." It was a time

of celebration for the grape harvest and, according to Johannes

Tzetzes (c. 1120�1183) a Greek author who wrote commentaries

on Homer and Hesiod, it was held when the must of the newly harvested

grapes had fermented. Other non-Hellenic peoples adopted these

festivals but turned them into orgies which the more sober Greeks

felt were "scandalous."

Hindu mythology has a drink termed

Amrita, believed to be derived from Sanskrit a-

(not) and a root word related to the Latin mort-, and

the Greek brot-. The gods of the Scandinavian pantheon

preserved their perpetual youth by eating apples guarded by one

named Idun. It is tempting to see this guardian figure

as a corruption of the word Eden!

Clearly, there has been preserved

among the nations a certain connection between alcohol and immortality,

a reversal of the biblical connection obviously, and perhaps

an illustration of just the kind of reversal that mythology experienced

when it made the serpent the symbol of health.

pg.14

of 14 pg.14

of 14  Copyright © 1988 Evelyn White. All rights

reserved

Previous Chapter Next

Chapter

Copyright © 1988 Evelyn White. All rights

reserved

Previous Chapter Next

Chapter

|