|

Abstract

Table

of Contents

Part I

Part II

Part III

Part IV

Appendixes

|

Part II: The Seed of the Woman

Chapter 16

And He Called Their Name Adam

Let us make man

in our image

and after our likeness.

(Genesis 1:26)

For (in Christ) there is neither male nor female:

for ye are all one in Christ Jesus.

(Galatians 3:28)

In the resurrection

they neither marry nor are given in marriage,

but are as the angels of God in heaven.

(Matthew 22:30)

Traditions of the

original bisexual nature of the first man and of his subsequent

reduction to two sexes by the formation of the first woman out

of him, are ancient and widespread. Probably the best known of

these traditions are those of the Greeks whose ideas on the subject

have been familiar to Classical scholars for centuries. Yet Jewish

and Christian commentaries had very early reached the same conclusion

on the basis of the Genesis account.

The Greeks seem to have derived

much of their mythology from Egypt, and Egypt in turn had derived

much of its mythology from Babylonia. In his Legends of the

Jews, Louis Ginsberg notes that according to the German scholar,

Jeremias (in a work available only in

pg.1

of 13 pg.1

of 13

German titled Altes

Testament im Lichte des Orients), the view that Adam was

originally andrognynous was familiar to the Babylonians. *

So far I have not been able to find any unequivocal

evidence of such a tradition in the currently available Cuneiform

literature, though Ginsberg's reputation as a scholar should

be sufficient authority. However, the Society of Biblical Archaeology

published a three volume work in 1873 which contains a useful

collection of Cuneiform texts relevant to Bible history translated

into English under the title Records of the Past,** but

there is no indication even in this collection of any such tradition.

Then in 1916, Barton published the first edition of his most

useful work Archaeology of the Bible,†

but again I found no evidence of any strictly parallel account

of the formation of Eve out of Adam. Nor, to my knowledge, has

one been added in later editions.

We now have Pritchard's authoritative

Ancient Near Eastern Texts and a careful reading of the

Sumerian 'Paradise Myth' reveals a brief incident towards the

end of this poem which might possibly provide a link with Genesis

2:21 and Adam's so-called 'rib,'‡

though it is certainly a tenuous one. We shall look into this

more carefully subsequently.|

Possibly the real source of Jeremias'

reference is, however, the rather obvious parallel account that

is to be found in the work of Berossus written about 260 B.C.

Francois Lenormant observed that this ancient historian, whose

works are known to us now only from quotations by other authors

of antiquity, has a statement to the effect that the first man

was created "with two heads, one that of a man and the other

that of a woman, united in the same body with both sexes combined."◊

From India we have traditions preserved

in the Rig Veda which, however, have none of the sobriety of

the biblical account though clearly pointing to a similar circumstance

relating to the constitution of the first man. According to the

Bundehesh, (chapter xv � a work dedicated to the exposition

of a complete cosmogony written in Pahlevi and known only from

the period subsequent to the conquest of Persia by the Mussulmans),

Ahuramazda completed his creative

* Ginsberg, Louis, Legends of the Jews,

Philadelphia, Jewish Publication Association of America,

1955, vol.V, From Creation to Exodus, p.88, note 42.

** Records of the Past: English Translations of Assyrian and

Egyptian Monuments, Society of Biblical Archaeology, London,

Samuel Bagster,1873, in 3 volumes.

† Barton, George, Archaeology of the Bible, Philadelphia,

American Sunday School Union, 1916.

‡ Pritchard, James B., Ancient Near Eastern Texts,

Princeton, 1969, p.40, 41, lines 263-266.

◊ Lenormant, Francois, The Beginnings of History,

New York, Scribners, 1891, p.62.

pg

2 of 13 pg

2 of 13

work by producing a certain

Gayomard, "the typical man." Unfortunately, Gayomard

was later put to death by an enemy of Ahuramazda but his seed

germinated in the earth and there sprang up a plant rather like

a rhubarb. In the centre of this plant was a stalk with a kind

of stamen in the form of a man and a woman joined together. Ahuramazda

divided them, endowed them with motion, and placed within each

of them an intelligent soul. Thus were born the first pair from

whom all human beings are descended.

A rather similar view is reflected

in the Cosmogony of Zatapatha Brahmana which is included in the

Rig Veda, though it is generally considered to be very much later

in origin � perhaps the fourteenth century B.C. or even as

late as the ninth century B.C. * It

is apparently highly fanciful, yet it does bear witness to a

very early tradition about the original androgynous nature of

man.

The same basic idea may also be

found in early Chinese literature. According to Lord Arundell

of Wardour, quoting L'Abbe Gainet, the Chinese cosmogony speaks

of the creation of men in the following way: "God took some

yellow earth and he made men of two sexes," which

is generally interpreted to mean bisexual.†

Plato, of course, is unequivocal.

In his Symposium (chapter XIV), he wrote: "Our nature

of old was not the same as now. It was then one man-woman, whose

form and name were common both to the male and to the female.

Then said Jupiter, 'I will divide them into two parts'."

Subsequently Plato remarks, "When their nature had been

bisected, each half beheld with longing its other self."

Plato elaborated his views in his work The Banquet by

having one of his characters, Aristophanes, say: "In the

beginning there were three sexes among men, not only the two

which we still find at this time as male and female, but also

a third which partook of the nature of each but which has now

disappeared, leaving only the name Androgyn behind."

Aristophanes' speech confuses the issue somewhat by proposing

that there were three sexes among men from the beginning, yet

the idea of androgynous man as the original type is clearly reflected

in Plato's reference to Jupiter's decision. Lenormant believed

that the whole idea, common to the Ionian School of Greek philosophers,

had been borrowed from Asia in the first place.

Empedocles (c. 495�435 B.C.),

a Greek philosopher of Agrigentum in Sicily, set forth a reconstruction

of the history of plant and animal

* Lenormant, Francois, ibid., p.62.

† Lord Arundell of Wardour, Tradition. Mythology

and Law of Nations, London, Burns, Oates, 1872, p.134.

pg.3

of 13 pg.3

of 13

life which foreshadowed

the theory of Evolution to some extent. It is highly fanciful,

but a propos of the present subject it is of interest.

The Encyclopedia Britannica article on his works states

his position as follows: *

His most interesting views dealt

with the origin of plants and animals, and with the physiology

of man. As the elements combined through the work of love, there

appeared quaint results � heads without necks, arms without

shoulders. Then as these structures met, there were heads and

figures of double sexes. But most of these disappeared as suddenly

as they arose; only in those rare cases where the several parts

were adapted to each other did the complex structures last. Soon

various influences reduced the creatures of double sex to a male

and a female, and the world was replenished with organic life.

The Romans,

of course, were much influenced by the Greeks, and like the Greeks

they seem to have held that a bisexual individual was a superior

one. In his book, The Religion of Greece in Prehistoric Times,

Axel Persson underscores how very ancient this idea was.†

The earliest deities were, like Cybele (the Mother of all other

gods) hermaphroditic. According to their most ancient beliefs,

Cybele generated the other deities by self-fertilization.

Greek thinking on this whole matter

influenced the Hellenized Jews, as it had influenced educated

Romans. Philo Judaeus (born about 20 B.C.) was one so influenced.

He was aristocratic, eloquent, and a well informed Pharisee who

seems to have been particularly familiar with the works of Plato.

Indeed, he attempted to reconcile the Mosaic system with Platonic

philosophy and is usually credited with having first made popular

among the Jews the concept of the Logos as intermediary between

God who is pure spirit and the physical world of matter. He became

one of the more notable intellectual opponents of the Christian

faith and his works were a source of constant concern to the

early Church Fathers as they sought to elaborate and construct

a Christian world view.

One of the much discussed issues

in both Jewish and Christian circles was this question of the

androgynous nature of Adam as first created. Philo, as shown

in his Quaestiones (1:19), was well acquainted with rabbinic

lore on this subject but he believed that the derivation of Eve

out of Adam was not sober history but allegory. To this many

of the Church Fathers took exception. In his Contra Celsus

(4:38),

* Encyclopedia Britannica, 1958 edition, vol.8, p.400.

† Persson, Axel, The Religion of Greece in Prehistoric

Times, University of California Press, 1942, p.106.

pg.4

of 13 pg.4

of 13

Origen observed that

Jews as well as many Christians considered the account of the

creation of Eve out of Adam to be allegory. But Louis Ginsberg,

when noting this fact, is careful to underscore that, "in

the earlier rabbinic literature now extant, no such allegorical

tendencies are known. Nor was Philo able to give firm sources

for his own views from rabbinical literature." *

Actually, according to Ginsberg,

Philo is himself contradictory and it is thus difficult to know

precisely what he believed. He seems to have thought that the

best explanation was that Genesis 1:27 ("male and female

created He them") implied a bisexuality and Genesis 2:7

("formed man of the dust of the ground") no sex at

all.†

Justin Martyr who lived from 100�165

A.D., in his Hortatory

* Ginsberg, Louis, Legends of the Jews,

Philadelphia, Jewish Publications Association of America,

1955, vol.V, From Genesis to Exodus, p.89.

† It is conceivable that Genesis 1:27, which seems

to relate the maleness and femaleness of man as created with

the image of God, is in fact telling us something about the nature

of God Himself. Perhaps part of the 'image' of God in man is

reflected in the compound of which we now observe only the two

elements. As originally united in Adam, that compound of male/femaleness

was an essential aspect of the divine image.

Karl Barth entertained such

a view. He held that the simplest exegesis of Genesis 1:27 would

equate a maleness and femaleness compound in Adam with the image

of God. The subsequent division of man into two sexes was for

man's own good by making him no longer self-sufficient and in

some real sense potentially asocial. An important aspect of the

image is the unity in fellowship between men and women under

ideal conditions and Barth makes much of the uniqueness of this

fellowship of love in purity [Church Dogmatics, vol.

III, chapter 1, translated by J. W. Edwards, et al, Edinburgh,

T. & T. Clark, 1958, p.214. See also Paul L Jewett, Man

as Male and Female, Grand Rapids, Eerdman's, 1975,

p.43ff., and G. C. Berkouwer who says, "Barth is convinced

that the text gives us a 'well-nigh definitive statement' of

the content of the image," Man the Image of God, Grand

Rapids, Eerdman's, 1975, p.72, footnote 16].

There is another aspect of the

male/female relationship in all higher forms of life. A. J. Thebaud

suggested some years ago that one of the earliest concepts of

the nature of God was hermaphroditic. "The principle of

deity is always accompanied by a goddess, commonly called his

wife but in reality his 'female energy' as we find in Hindustan,

in the case of Siva in particular" [Gentilism: Religion

Previous to Christianity, New York, D. & J. Sadlier &

Co., 1876, p.254].

The supposed 'wife figure' is taken

in this view to be a symbol of the deity's creative principle

or energy. Some early Egyptian statues show 'God' as a giant

figure signifying strength and majesty, while his generative

energy is represented by a female figure, often relatively small

in size, placed beside him.

Ideas of this kind tend to be discounted

today. Our culture is fatally inoculated with the view that the

new is better than the old, that novelty (even in ideas) is itself

a virtue. Modern intelligence in such matters so far outstrips

the intelligence of writers of only a century ago (let alone

millennia ago) that such views can be quite safely ignored. Tradition

was once held in very high regard, but it is now argued that

this was due to lack of sophistication in former times.

But little by little we have come

to accord greater respect to the thoughts of earlier times and

have discovered how often archaeological findings have vindicated

these ancient traditions � not just in a general way but

almost always in a highly specific and detailed fashion. It could

be that many of the traditions, and some of the symbols that

were anciently shared by many nations about the original nature

of man as a special creature of God and created in his image,

reflect the truth of the matter in ways we did not suspect.

pg.5

of 13 pg.5

of 13

Address to the Greeks

(chapter 30) follows Philo almost

literally in his explanation of the double account in Genesis,

but I do not think for one moment that he shared his cynicism.

Tertullian, who lived from 160 to 230 A.D., in his Adversus

Hermogenem (chapter 26), and Hippolytus (died c.230 A.D.)

both agree with the rabbinical view (Baraita 32 and Middoth,

no.12) which held that the Bible gives first a general account

and then a detailed one. That the rabbis truly believed Adam

was originally hermaphroditic is clear enough from a number of

sources, though they elaborated this simple truth along rather

fanciful lines. Louis Ginsberg gives a number of references,

* and leaves one with the impression that these are merely some

out of many.

The Soncino

Chumash, edited by A. Cohen, has a

note on Genesis 1:27 by the famous rabbinical scholar Rashi (born

1040, died 1105 in the Rhineland) who wrote a commentary on the

Pentateuch and was credited with "an encyclopedic knowledge

of rabbinic literature," in which the rabbi says, "The

Midrash explains that man as first created consisted of

two halves, male and female, which were afterwards separated."†

One of the most famous rabbis of

Medieval times and one of the most philosophical expounders of

Judaism was a man named Moses ben Maimon (1135�1202 A.D.),

who is more popularly known as Maimonides. He strongly supported

the view that Adam was created as a man-and-woman being, having

two faces turned in opposite directions, and that during a stupor

the Creator separated his genuine feminine half (Hawah, Eve)

from him in order to make of her a distinct and separate person.

A century later, Nahmanides (1220�1250)

in his commentary on Genesis 1:1-6:8 which has been recently

translated by Jacob Newman, has this to say on Genesis 1:27,

"[Adam and Eve] were created with two faces." Newman

in a note (#144) interprets this to mean, "hermaphroditic."‡

Now The Jerusalem Targum, which

may have been begun as early as the second century B.C., amplified

the text of Genesis 2:21 and said that "Eve was formed out

of the third rib on the right side"! Whatever may be said

of this kind of comment, it is surely quite clear that Hebrew

scholars were interpreting the record very literally. They

* Louis Ginsberg's references: Midrash

Bereshith Rabbah on Genesis, chapter 8, paragraph 1, and

chapter 17, paragraph 6; Berakoth, chap.ter 61a, a Talmudic

Tractate on Prayers and Benedictions; 'Erubin, chapter

18a, a Talmudic Tractate on the Sabbath; Midrash Weyikra Rabbah,

chapter 14; Midrash Tanchuma hagidom Wahishan, Book

III, p.32; Midrash Tehillim, chapter 139, p.529; Midrash

Tanchuma Tazria, 2.

† Cohen, A., The Soncino Chumash, London, Soncino

Press, 1964, p.ix, 7.

‡ Newman, Jacob, Commentary by Nahmanides, Leiden,

Brill, 1960, p.xx.

pg.6

of 13 pg.6

of 13

understood that a real

cleavage by some kind of surgical operation divided Adam into

complementary selves which, being thereafter "joined"

in true marriage, were reconstituted as "one flesh."

Modern Jewish scholars still either hold to this view or acknowledge

it as by no means impossible; even those medically trained agree.

Dr. Robert Greenblatt, in his little book Search the Scriptures,

remarks in this connection: *

Metaphorically we may assume

that the original man, Adam, was hermaphroditic. Such an assumption

is quite permissible, for it is twenty-one verses after reporting

the creation of man that Genesis (2:18) tells us "and the

Lord God said, It is not good that man should be alone: I will

make a help meet for him."

In this history of human events is thus recorded man's earliest

conception of the establishment of the sexes. Some of the most

distinguished Hebrew writers, according to Hans Selye, interpret

the first chapters of Genesis as describing Adam as being of

both sexes.

So now we may find

it proper to trace back our ancestry until we arrive at a first

father who carried in himself both seeds, and after the division

had been effected, sinned and introduced into his body some disturbing

agent which has upset the normal transmission of the chromosomal

allotment assigned originally by God to each sex once they had

been separated. Any such disturbance, arising from chromosomal

anomaly, surely suggests that the potential for both sexes is

still resident in suppressed form in each individual. Such is

the stuff of inheritance in all of us, a fact which seems to

point to a past when the potential was effectively resident in

a single person, and then to some occasion when the potential

was modified � though not without leaving a vestige of itself

to remind us that it is indeed a modification.

The quote from the Jerusalem

Targum above brings us to a consideration of the meaning of the original

Hebrew word (  tsela'), rendered RIB in virtually all our English translations.

The Jewish version of this Targum by members of the famous Ibn Tibbon

family (of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, A.D.), and the version

of Maimonides, both translate this word as side rather than rib.†

This is not surprising since the Septuagint translators employed the Greek

word pleuran (

tsela'), rendered RIB in virtually all our English translations.

The Jewish version of this Targum by members of the famous Ibn Tibbon

family (of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, A.D.), and the version

of Maimonides, both translate this word as side rather than rib.†

This is not surprising since the Septuagint translators employed the Greek

word pleuran ( )

which, if we are to be guided at all by )

which, if we are to be guided at all by

* Greenblatt, Robert, Search the Scriptures,

Montreal, Lippincott, 1963, p.50.

† Tibbon: see Robert Tuck, Age of the Great Patriarchs,

London, Sunday School Union, no date, p.102.

pg.7

of 13 pg.7

of 13

New Testament usage has

only the meaning of side. It appears in John 19:34; 20:20,

25, 27; Acts 12:7. It is important to notice that this is the

meaning attached to it in the New Testament Greek. Since the

New Testament rests heavily for its usage of Greek words upon

that already adopted by the seventy-two who gave us the Septuagint,

one should assume, I think, that the latter's use of pleura

for tsela' indicates how they also understood the

word: i.e., as side rather than rib.

Furthermore, the

Hebrew word tsela' is only translated RIB in English versions

in this one place. Its renderings elsewhere, as in the King James

Version for instance, are such as the following: beam, chamber

(twice), plank, corner (twice), side chamber (9

times), and side (19 times). The rendering side appears

mainly in connection with descriptive details of the tabernacle

� in Exodus 25:12, 14; 26:27, 35; 27:7; 36:25, 31, 32; 37:3;

38:7; 2 Samuel 16:13; and Job 18:12. These are all the occurrences

in which the word appears. In some of them it is so translated

twice in a single verse. In the Latin Vulgate it is rendered

side; as it is also in the Syriac version. It is therefore

all the more surprising that so few modern English versions have

adopted it in Genesis.

The question is, What really is

the best word to use? If we allow ourselves to be guided by the

passages in which it is rendered side-chamber, we have

possibly a closer approach to what may have been the intent of

the original. The word is so rendered nine times in the following

places: Ezekiel 41:5, 6 (twice), 7, 8, 9 (twice), 11, and 26.

Ellicott in his Commentary is surely correct in saying

that "Adam could hardly have felt the loss of one rib out

of 24 actual bones with which the body is provided � much

less in view of the fact that the wound was completely healed

after the operation." Whether he would have been aware of

the disappearance of some internal organ such as a gonad or a

fully developed ovary is a moot point. But he might very well

have become aware of a new need, directed towards the woman.

It is worth noting in passing that,

according to Moulton and Milligan, the general extra-biblical

meaning of the Greek word used in the Septuagint is side of

a human being or lung or chest. But it is also

noted that "an unusual use of the word is vessel, as

found in one papyrus of the late third century A.D. in reference

to some glass vessels." *

Liddell and Scott

in their Lexicon of Classical Greek give the meaning of

pleuron as rib, equating it with Herodotus' use

of the word, but as they point out, "mostly in the plural

like the Latin costae, i.e.,

* Moulton, James H. and George Milligan, VocabuIary

of the Greek Text: Illustrations from the Papyri and Other

Non-Literate Sources, Grand Rapids, Eerdmans, 1972, p.518.

pg.8

of 13 pg.8

of 13

'side' of a man."

They give a secondary meaning as "the membrane that lines

the chest." A third meaning is as the side of a rectangle,

and a fourth meaning as a page of a book. It has also, they observe,

the sense of wife. This is interesting in that among the

Arabs a cognate word of the Hebrew tsela' is used to signify

a bosom friend, a person who is "at one's side." *

None of these comments are decisive, but I think in general they

certainly allow the choice of the word side rather than

rib as a meaningful translation of the Hebrew of Genesis

2:21.

Turning to the very

oldest actual documents we have, i.e., cuneiform tablets, we

find some curious indications that the Hebrew word tsela'

had a more profound significance than merely the designation

of one of Adam's ribs. One of the best authorities on Sumerian

Cuneiform literature, Samuel Kramer, in his book From the

Tablets of Sumer† notes

that the Sumerian word for rib is TI (pronounced TEE).

Now this sound value associated with the word TI forms part of

several names under rather interesting circumstances.

Some of the earliest tablets tell us that the name of one of

the gods was EN-KI. This name seems to be compounded from two

words meaning Heaven (and) Earth, a circumstance

which may reflect something about the supposed nature of the

being who bore the name. There is little doubt from a study of

Sumerian mythology that EN-KI was really the counterpart of original

man, exalted to the status of a deity. We are told that EN-KI

became sick, and the sickness affected eight parts of his body

� an observation which is probably intended to indicate only

that the whole man was sick. The tablet which gives us

the details of this event also spells out where the sickness

afflicted him, although some of the words are not now decipherable.

They do include his head, his arms and his chest. The ailment

arose because of EN-KI's disobedience in eating a fruit which

he had been expressly forbidden to eat and which is identified

as a cassia plant, of which we have already spoken.

Being a highly favoured creature

of the gods, steps were at once taken to heal him, and for this

purpose a goddess was specially created. Her name was NIN-TI,

which is a compound of two words meaning "the lady of the

rib." Kramer tells us that NIN-TI came to be known later

as "the lady who makes live." Thus the same compound

name, NIN-TI, acquired by association two different meanings.

The first compound (NIN) kept its sound value and meaning, but

TI came to be

* Skinner, John, Commentary on Genesis,

Edinburgh, T. & T. Clark, 1930, 2nd edition, p.63.

† Kramer, Samuel, From the Tables of Sumer, Indian

Hills, Colorado, Falcon's Wing Press, 1956, p.172f.

pg.9

of 13 pg.9

of 13

associated with both

"the rib" and "the one who gives life." The

student of Scripture will see at once that we have here what

looks like a confused reflection of the grand truth set forth

in Genesis 2:21 and 3:20 which shows Eve as first formed from

a tsela' (translated more correctly, I think, as side),

later to become "the mother of all living." If

EN-KI is equated with Adam, then clearly the female NIN-TI, created

to heal the only ailment from which a perfect Adam could be suffering

(i.e., a sense of aloneness) would logically be equated with

Eve.

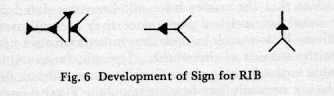

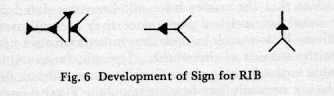

What Kramer did not note in either

of the books in which he has made particular reference to this

matter, * is the fact that the cuneiform sign or ideograph for

TI sheds its own interesting light on the meaning of the word

translated rib. In Rene

Labat's Manuel d'Epigraphie Akkadienne,†

the cuneiform sign for TI is written as at (a) in Fig. 6,

in late Assyrian. But in the very earliest texts known this sign

appeared as in (b), which is clearly the same pictograph in simplified

form. However, it is known that these cuneiform signs were very

early turned through 90 degrees for some reason, so that they

were originally written in the upright position. The sign shown

in (b) would therefore have been drawn at first as shown in (c);

and there seems to be little doubt that it was once a simplified

picture of a woman wearing a skirt.

The word

values which Labat attaches to the sign are various. They include

rib or side member (of a vehicle or a boat); but

the sign also forms part of the verb "to make alive."

We know from later texts employing this sign how it was to be

pronounced. The sign was not merely read as TI (as among the

Sumerians) but by the Babylonians as TSILU, which is readily

seen to be related to the Hebrew TSELU.

The Babylonians adopted the earlier

Sumerian ideographs and used them to signify the same objects

as the Sumerians had, but they applied to them their own sound

values which were usually (though

* Kramer, Samuel, From the Tablets of Sumer,

Indian Hills, Colorado, Falcon's Wing Press, 1956,

p.172 f., or The Sumerians, University of Chicago Press,

1965, p.149 f.

† Labat, Rene, Manuel d'Epigraphie Akkadienne,

Paris, Imprimerie Nationale de France, 1952, p.68, 69.

pg.10

of 13 pg.10

of 13

not always) somewhat

different. This is a widespread practice. The Japanese did precisely

the same thing when they adopted the Chinese ideographs in order

to put their own language into writing. Looking at the sign  the Sumerians would read it as

TI but the Babylonians and Assyrians would read it as TSILU.

Each of them would immediately picture in their minds either

a RIB (or a side, depending upon which is the correct

interpretation) or LIFE-GIVING WOMAN, depending upon the context.

The word used in the Hebrew of Genesis 2:21 (tsela')

is certainly a cognate Semitic word with the Babylonian and

Assyrian TSILU. the Sumerians would read it as

TI but the Babylonians and Assyrians would read it as TSILU.

Each of them would immediately picture in their minds either

a RIB (or a side, depending upon which is the correct

interpretation) or LIFE-GIVING WOMAN, depending upon the context.

The word used in the Hebrew of Genesis 2:21 (tsela')

is certainly a cognate Semitic word with the Babylonian and

Assyrian TSILU.

The reader may be misled here into supposing that I am supporting

the view that the Sumerian language is earlier than Semitic languages

such as Assyrian, Babylonian and Hebrew. It is at present true

that the earliest records (tablets) are in Sumerian. But this

is by no means absolute proof of any priority of the Sumerian

language over Semitic. For reasons which have been elaborated

elsewhere, * I am persuaded that the language of Noah and his

family was not Sumerian but Semitic in form � not necessarily

Hebrew, though it might have been proto-Hebrew. One of the strongest

arguments in favour of this assumption is that the names of his

immediate descendants as set forth in Genesis 10 are clearly

Semitic words which, for the most part, have recognizable meanings

even in Hebrew as we know it today.

It is clear that

the names have not been translated or modified radically from

their original form, since they are still preserved with comparatively

little change in their descendants who are now found to constitute

the nations of the world. Japheth, for example, is clearly recognizable

in the Japetos of the Greeks whose ancestor he is, though

the Greeks are certainly not Semitic people. These names have

been carefully traced by the author in another work.†

The importance of this fact is that people do not give their

children names which are entirely foreign to their own language.

We do have a notable exception in the case of biblical names

adopted in Christian families, but this is a special situation

that did not apply on any wide scale in pre-Christian times.

A Chinaman who happened to be a metalworker would not call his

son Smithson, because Smith is an English word,

not a Chinese one.

People customarily give their children

names that are meaningful in their own language, and the forms

of such names provide a clue to

* Custance, Arthur, "The Confusion of Languages"

Part V in Time

and Eternity, vol.6 of the Doorway Papers Series, Grand Rapids,

Zondervan, 1977.

†

Custance, Arthur, "A Study of the Names in Genesis 10" Part

II in Noah's Three Sons, vol.1 of the Doorway Papers Series,

Grand Rapids, Zondervan, 1975.

pg.11

of 13 pg.11

of 13

the language spoken

by those who use them. When Noah and his family gave names to

their children they were clearly speaking Hebrew or something

akin to it: and if Noah was doing so, it is a fair assumption

to say that Adam also spoke the same form of language since the

confusion of languages was much later.

From which I would conclude that

the supposedly later form of the word tsela' is not in

fact later at all, but the original. The form is only assumed

to be earlier because historical accident has placed in our hands

Sumerian tablets in which the word TI appears and these happen

to be earlier than any tablets in which the word TSILU occurs.

We do not have any tablets, yet, which truly come from the pre-Flood

world, but it seems virtually certain that a society which had

metallurgy and could construct an ark larger than any vessel

till quite modern times must have had some method of keeping

adequate records.

It does not seem likely that we

can filter from such indistinct leads very much in the way of

concrete information of substantive value, but certainly there

is a story here the details of which in the Scriptural account

are clear enough. The biblical record is free of the exaggerations

and absurdities which mar all the pagan traditions. It is sensible

to view it as the original.

I do not think it altogether unreasonable

to assume that when Adam exclaimed, "This is now bone of

my bone and flesh of my flesh," he had an intuitive

understanding of the fact (or was it revealed?) that Eve had

been formed from something much more fundamental to himself and

to his nature and constitution than merely one of his ribs. The

supplementary statement made afterwards, "and they shall

be one flesh," surely implies more than that Eve would in

some mystical way merely make up for a missing rib � especially

in view of the fact that man does not have, and is unlikely ever

to have had, an odd rib on one side.

Adam was in no position to be able

to understand in precisely what way he had been "divided"

even if God had revealed to him the magnitude of the operation.

But it seems rather certain that if Eve had merely been formed

from one of his ribs and the wound had then been completely

repaired, he would hardly have discerned in Eve a creature so

complementary to himself in such a profound way. His sense of

her complementarity was initially psychological not anatomical,

though he felt it so concretely that he expressed it in anatomical

language. And surely, the two becoming one flesh when truly married

reinforces the concept of an original "unity."

It is an interesting thing to note

in the Sumerian account that the "Lady of the Rib"

was formed in a way which was notable for the speed with which

it all happened while not yet being actually instantaneous. The

normal nine months gestation period is reduced in the

pg.12

of 13 pg.12

of 13

poem to a mere nine

days: a day for a month. Perhaps this was a way of saying that

this "Lady who makes alive" was not formed by the ordinary

processes familiar in human generation nor yet by a process totally

independent of it, but by some quite exceptional means of which

not the least remarkable factor was the short time it took to

complete the operation. But it was an operation; it did

take time; it was not instantaneous creation but formation.

* (Genesis 2:22).

And so we can perhaps

add to the evidence from physiology the confirming voice of tradition,

confused as it is, as well as the considered opinion of the more

famous Jewish commentators who evidently found the Genesis account

leading them to a similar conclusion: Eve was literally formed

out of the man because Adam as first created was truly androgynous.

I believe he was androgynous not only physiologically speaking

but in the very essence of his nature also: hormonally, he was

truly male and female.

There are other important reasons why such

a truly androgynous constitution should have characterized the

first man, and these have to do with the method by which God

was to redeem the race that sprang quite literally from Adam's

loins, of one, i.e., a single individual, not "of one

blood" (Acts 17:26) as the King James Version has

it.† And this is the subject

of the next chapter.

* The Hebrew word used is banah  , meaning "to build."

, meaning "to build."

† It is widely agreed by scholars of evangelical as

well as liberal persuasion that the word blood should

be omitted as it is in a number of MSS. This is the procedure

followed in the RV, RSV, Rotherham, Berkeley, and many others.

pg.13

of 13 pg.13

of 13  Copyright © 1988 Evelyn White. All rights

reserved

Previous Chapter Next

Chapter

Copyright © 1988 Evelyn White. All rights

reserved

Previous Chapter Next

Chapter

|