|

Abstract

Table of Contents

Part I

Part II

Part III

Part IV

Part V

|

Part II: A Study of the Names in Genesis10

Chapter 5

Tbe Widening Circle

IT SEEMS unlikely,

even making all conceivable allowances for gaps in the text,

which some are persuaded must exist, that one could push back

the date of the Flood and with it the date of the events outlined

in this Table of Nations, beyond a few thousand years B.C. At

the very most these events can hardly have occurred much more

than 6000 years ago � and personally, I think 4500 years

is closer to the mark. In this case, we are forced to conclude

that, except for those who lived between Adam and Noah and were

overwhelmed by the Flood and whose remains I believe are never

likely to be found, all fossil men, all prehistoric peoples,

all primitive communities extinct or living, and all civilizations

since, must be encompassed within this span of a few thousand

years. And on the face of it, the proposal seems utterly preposterous.

However, in this chapter I hope to show

that there are lines of evidence of considerable substance in support

of the above proposition. In setting this forth, all kinds of "buts"

will arise in the reader's mind if he has any broad knowledge of current

physical anthropology. An attempt is made to deal with some of these "buts"

in four other Doorway Papers: "Fossil Man and the Genesis

Record", "Primitive Cultures: Their Historical Origins",

"Longevity in Antiquity and Its Bearing on Chronology", and

"The Supposed Evolution of the Human Skull". Yet some problems

remain unsolved. However, one does not have to solve every problem before

presenting an alternative view.

It is our contention that Noah and his

wife and family were real people, sole survivors of a major catastrophe,

the chief effect of which was to obliterate the previous civilization

that had developed from Adam to that time. When the Ark grounded,

* Custance, Arthur, "Fossil Man and the

Genesis Record", Part I and "Primitive Cultures: Their

Historical Origins", Part II and "The Supposed Evolution

of the Human Skull", Part IV, in Genesis and Early Man,in

Genesis and Early Man, vol.2; "Longevity in Anitquity

and Its Bearing on Chronology", Part I in The Virgin

Birth and the Incarnation, vol.5 � all in The Doorway

Papers Series.

pg

1 of 23 pg

1 of 23

there were 8 people alive

in the world, and no more. Landing somewhere in Armenia, they

began to spread as they multiplied, though retaining for some

time a homogeneous cultural tradition. The initial family pattern,

set by the existence in the party of three sons and their wives,

gave rise in the course of time to three distinct racial stocks

who, according to their patriarchal lineage, are most properly

termed Japhethites, Hamites, and Shemites, but in modern terminology

would be represented by the Semitic people (Hebrews, Arabs, and

ancient nations such as Babylonians, Assyrians, etc.), the Mongoloid

and Negroid Hamites, and the Caucasoid Japhethites.

At first they kept together. But

within a century or so they broke up into small groups, and subsequently

some of the family of Shem, most of the family of Ham, and a

few of the family of Japheth arrived from the east in the Mesopotamian

Plain (Genesis 11:2). Here it would appear from evidence discussed

elsewhere that the family of Ham, who had become politically

dominant, initiated a movement to prevent further dispersal by

proposing the building of a monument as a visible rallying point

on the flat plain, thus bringing upon themselves a judgment which

led to an enforced and rapid scattering throughout the earth.

This circumstance accounts for

the fact that in every part of the world where Japheth has subsequently

migrated he has always been preceded by Ham � a fact which

applies in every continent. In prehistoric times this is always

found to be true, the earliest fossil remains being Negroid or

Mongoloid in character, but those who followed were not. Indeed,

in protohistoric times whatever cultural advances the pioneering

Hamites had achieved tended to be swallowed up by the succeeding

Japhethites. The record of Japheth's more leisurely spread over

the earth has been marred by the destruction of both the culture

and their Hamite creators wherever the Japhethites arrived in

sufficient force to achieve dominion. This happened in the Indus

Valley, it happened in Central America, it happened to the Indian

tribes of North America, it happened in Australia, and only numerical

superiority has hitherto preserved Africa from the same fate.

The indebtedness of Japheth to Ham for his pioneering contribution

in mastering the environment is amply explored and documented

in Part IV of this volume, "The Technology of Hamitic People,"

and its complement, Part I, "The Part Played by Shem, Ham,

and Japheth in Subsequent World History." The evidence will

not be repeated here.

pg.2

of 23 pg.2

of 23

Now,

in spite of South African discoveries of recent years, it still

remains true that whether we are speaking of fossil man, ancient

civilizations, contemporary or extinct native peoples, or the

present world population, all lines of migration that are in

any way still traceable are found to radiate from the Middle

East.

The pattern is as follows. Along

each migratory route settlements are found, each of which differs

slightly from the one that preceded it and the one that follows

it. As a general rule, the direction of movement tends to be

shown by a gradual loss of cultural artifacts, which continue

in use back along the line but either disappear entirely forward

along the line or are crudely copied or merely represented in

pictures or in folklore. When several lines radiate from a single

centre, the picture presented is more or less a series of ever

increasing circles of settlement, each sharing fewer and fewer

of the original cultural artifacts which continue at the centre.

At the same time completely new items appear, which are designed

to satisfy new needs not found at the centre. The further from

the centre one moves along such routes of migration, the more

new and uniquely specific items one is likely to find which are

not shared by other lines, but there remain some recollections

of a few particularly important or useful links with the original

homeland. Entering such a settlement without previous knowledge

of the direction from which the settlers came, one cannot be

certain which way relationships are to be traced. There is, however,

usually some dependable piece of evidence which allows one to

separate the artifacts which have been brought in from those

that have been developed on the site. This is particularly the

case whenever complex items turn up requiring materials which

would not be available locally. Sometimes the evidence is secondhand,

existing in the presence of an article which is clearly a copy

and has something about its construction which proves it to be

so. For example, certain Minoan pottery vessels are clearly copies

of metal prototypes, both in the shape they take and in their

ornamentation. (138)

Where the pottery handles of these vessels join the vessel itself,

little knobs of clay are found which serve no functional purpose,

but which are clearly an attempt to copy the rivets which once

secured the metal handle to the metal body of the prototype.

These prototypes are found in Asia Minor, and it is therefore

clear

138. See on this J. D. S. Pendlebury, The

Archaeology of Crete, Methuen, London, 1939, p.68 and V.

G. Childe, Dawn of European Civilization, Kegan Paul,

5th edition, 1950, p.19.

pg.3

of 23 pg.3

of 23

which way the line of

migration is to be traced, for it is inconceivable that the pottery

vessel with its little knobs of clay provided the metal worker

with the clues as to where he should place his rivets.

In the earliest migrations which, if we

are guided by the chronology of Scripture, must have been quite rapid,

it was inevitable that the tendency would be more markedly towards a loss

of cultural items common to the centre as one moves out, rather than a

gain of new items. (139)

Thus the general level of culture would decline, although oral traditions,

rituals, and religious beliefs would change more slowly. In due time,

when a large enough body of people remained in any one place, a new "centre"

would arise with many of the old traditions preserved but some new ones

established with sufficient vigour to send out waves of influence both

forwards and backwards along the line.

Accompaning such cultural losses in the

initial spread of the Hamitic peoples would be a certain coarsening of

physique. Not only do people tend to be in many cases unsuited for the

rigours of pioneering life and be culturally degraded as a consequence,

but the nourishment itself often is grossly insufficient or unsuitable,

and their bodies do not develop normally either. As Dawson has observed,

(140) the more highly cultured

an immigrant is when he arrives, the more severely he is handicapped and

likely to suffer when robbed of the familiar accouterments of his previous

life. This has been noted by those who have studied the effects of diet

on the human skull for example, and this subject is dealt with in some

detail in "The Supposed Evolution of the Human Skull" (contained

in vol.2 of this series); and with respect to culture, in "Primitive

Cultures: Their Historical Origins" (in vol.2) .

The occasional establishment of what might

be called "provincial" cultural centres along the various routes

of migration has greatly complicated the pattern of relationships in protohistoric

times, yet the evidence which does exist, for all its paucity at times,

strongly supports a Cradle of Mankind in the Middle East from which there

went out successive waves of pioneers who were neither Indo-Europeans

nor Shemites. These were Hamitic pioneers, either Mongoloid or Negroid

in type with some admixture, who blazed trails and opened up territories

in every

139. Perry, W. J., The Growth of Civilization,

Pelican, 1937, p.123.

140 Dawson, Sir William, 'I'he Story of the Earth and Man,

Hodder and Stoughton, London, 1903, p.390.

pg.4

of 23 pg.4

of 23

habitable part of the

earth and ultimately established a way of life in each locality

which at a basic level made maximum use of the raw materials

and resources of that locality. The Japhethites followed them,

building upon this foundation and taking advantage of this basic

technology in order to raise in time a higher civilization, sometimes

displacing the Hamites entirely, sometimes educating their teachers

in new ways and then retiring, and sometimes absorbing them so

that the two racial stocks were fused into one.

So much for the broad picture We

shall now turn to a more detailed examination of the evidence

that (a) the dispersion of man took place from a centre somewhere

in the Middle East, and (b) that those who formed the vanguard

were of Hamitic stock.

Before man's evolutionary

origin was proposed it was generally agreed that the Cradle of

Mankind was in Asia Minor, or at least in the Middle East. Any

evidence of primitive types elsewhere in the world, whether living

or fossil, were considered proof that man became degraded as

he departed from the site of Paradise. When Evolution seized

the imagination of anthropologists, primitive fossil remains

were at once hailed as proof that the first men were constitutionally

not much removed from apes. One problem presented itself however,

the supposed ancestors of modern man always seemed to turn up

in tle wrong places. The basic assumption was still being made

that the Middle East was the home of man and therefore these

primitive fossil types, which were turning up anywhere but in

this area, seemed entirely misplaced. Osborn, in his Men of

the Old Stone Age, accounted for this anomaly by arguing

that they were migrants. (141) He asserted his conviction that both the human and

animal inhabitants of Europe, for example, had migrated there

in great waves from Asia and from Africa. He wrote, however,

that it was probable that the source of the migratory waves was

Asia, north Africa being merely the route of passage. This was

his position in 1915, and when a third edition of his famous

book appeared in 1936, he had modified his original views only

slightly. He had a map of the Old World with this subscription,

"Throughout this long epoch Western Europe is to be viewed

as a peninsula, surrounded on all sides by the sea and stretching

westwards from the great land mass of eastern Europe and Asia

-- which was the chief theatre of evolution, both of animal and

human life."

141. Osborn, H. F., Men of the Old Stone

Age, New York, 1936, pp.19ff.

pg.5

of 23 pg.5

of 23

However,

in 1930, and contrary to expectations, Prof. H. J. Fleure had

to admit: (142)

No clear traces of the men and

cultures of the later part of the Old Stone Age (known in Europe

as the Aurignacian, Solutrean, and Magdalenian phases) have been

discovered in the central highland of Asia.

The situation

remained essentially the same when W. Koppers in 1952 observed:

(143)

It is a remarkable fact that

so far all the fossil men have been found in Europe, the Far

East, and Africa, that is, in marginal regions of Asia that are

most unlikely to have formed the cradle of the human race. No

remains are known to us from central Asia where most scholars

who have occupied themselves with the origin of men would place

the earliest races.

It is true that some

fossil men have now been found in the Middle East, but far from

speaking against this area as being central to subsequent migration,

they seem to me to speak indirectly -- and therefore with more

force -- in favour of it. We shall return to this subsequently.

Prof. Griffith Taylor of the University

of Toronto, speaking of migratory movements in general, whether

in prehistoric or historic times, wrote: (144)

A series of zones is shown to

exist in the East Indies and in Australasia which is so arranged

that the most primitive are found farthest from Asia, and the

most advanced nearest to Asia. This distribution about Asia is

shown to be true in the other "peninsulas" [i.e., Africa

andEurope, ACC], and is of fundamental importance in discussing

the evolution and ethnological status of the peoples concerned.

. . .

Which ever region we consider,

Africa, Europe, Australia, or America, we find that the major

migrations have always been from Asia.

After dealing

with some of the indices which he employs for establishing possible

relationships between groups in different geographical areas,

he remarks: (145)

How can one explain the close

resemblance between such far-distant types as are here set forth?

Only the spreading of racial zones from a common cradle-land

[his emphasis] can possibly explain these biological affinities.

142. Fleure, H. J., The Races of Mankind,

Benn, London, 1930, p.45.

143. Koppers, W., Primitive Man and His World Picture,

Sheed and Ward, New York, 1952, p.239.

144. Taylor, Griffith, Environment, Race and Migration,

University of Toronto Press, 1945, p.8.

145. Ibid., p.67.

pg.6

of 23 pg.6

of 23

Then,

subsequently, in dealing with African ethnology, he observes:

(146)

The first point of interest

in studying the distribution of the African peoples is that the

same rule holds good which we have observed in the Australasian

peoples. The most primitive groups are found in the regions most

distant from Asia, or what comes to the same thing, in the most

inaccessible regions. . . .

Given these conditions its seems

logical to assume that the racial zones can only have resulted

from similar peoples spreading out like waves from a common origin.

This cradleland should be approximately between the two "peninsulas,"

and all indications (including the racial distribution of India)

point to a region of maximum evolution not far from Turkestan.

It is not unlikely that the time factor was similar in the spread

of all these peoples.

In a similar

vein Dorothy Garrod wrote: (147)

It is becoming more and more

clear that it is not in Europe that we must seek the origins

of the various paleolithic peoples who successfully overran the

west. . . . The classification of de Mortillet therefore only

records the order of arrival [my emphasis] in the West

of a series of cultures, each of which has originated and probably

passed through the greater part of its existence elsewhere.

So also wrote

V. G. Childe: (148)

Our knowledge of the Archaeology

of Europe and of the Ancient East has enormously strengthened

the Orientalist's position. Indeed we can now survey continuously

interconnected provinces throughout which cultures are seen to

be zoned in regularly descending grades round the centres of

urban civilization in the Ancient East. Such zoning is the best

possible proof of the Orientalist's postulate of diffusion.

Henry Field

in writing about the possible cradle of Homo sapiens, gives a

very cursory review of the chief finds of fossil man (to that

date, 1932), including finds from Pekin, Kenya Colony, Java,

Heidleberg, (Piltdown), and Rhodesia, and then gives a map locating

them; and he remarks: (149)

146. Ibid., pp.120, 121.

147. Garrod, Dorothy, "Nova et Vetera: A Plea for a New

Method in Paleolithic Archaeology," Proceedings of the

Prehistoric Society of East Anglia, vol.5, p.261.

148. Childe, V. G., Dawn of European Civilization, Kegan

Paul, London, 3rd edition, 1939. In the 1957 edition, Cllilde

in his introduction invites his readers to observe that he has

modified his "dogmatic" orientation a little but he

still concludes at the end of the vohlme (p.342), "the primacy

of the Orient remains unchallenged."

149 Field, Henry, "The Cradle of Homo Sapiens," American

Journal of Archaeology, Oct.-Dec., 1932, p.427.

pg.7

of 23 pg.7

of 23

It does

not seem probable to me that any of these localities could have

been the original point from which the earliest men migrated.

The distances, combined with many geographical barriers, would

tend to make a theory of this nature untenable. I suggest that

an area more or less equidistant from the outer edges of Europe,

Asia, and Africa, may indeed be the centre in which development

took place.

It is true that

these statements were written before the recent discoveries in

South Africa, or in the Far East at Choukoutien, or in the New

World. Of the South African finds little can be said with certainty

and there is no unanimity as to their exact significance. The

finds at Choukoutien, as we shall attempt to show, actually support

the present thesis in an interesting way. As for the New World,

nobody has ever proposed that it was the Cradle of Mankind. Thus

the Middle East still retains priority as the probable original

Home of Man. Nevertheless, as to dating, it must be admitted

that no authority with a reputation at stake would ever propose

it was a homeland so recently as our reckoning of only 4500 years

ago. The time problem remains with us and at the moment we have

no answer to it, but we can proceed to explore the lines of evidence

which in all other respects assuredly support the thesis set

forth earlier in this chapter.

Part of this evidence, curiously,

is the fact of diversity of physical type found within what appear

to have been single families. This has been a source of some

surprise and yet is readily accounted for on the basis of a central

dispersion. Some years ago, W. D. Matthew made the following

observation: (150)

Whatever agencies may be assigned

as the cause of evolution in a race, it should be at first most

progressive at its point of original dispersal, and it will continue

this process at that point in response to whatever stimulus originally

caused it, and will spread out in successive waves of migration,

each wave a stage higher than the preceding one. At any one time,

therefore, the most advanced stages should be nearest the centre

of dispersal, the most conservative stages the furthest from

it.

Some comment

is in order on this observation because there are important implications

in it. Lebzelter (151) pointed

out that "where man lives in large conglomerations, race

(i.e., physical form) tends to be stable while culture becomes

specialized: where he lives in small isolated groups, culture

is stable but

150. Matthew, W. D., "Climate and Evolution,"

Annals of the New York Academy of Science, vol.24, 1914,

p.80.

151. Lebzelter: quoted by W. Koppers in his Prirnitive Man,

p.220. His view was sustained by LeGros Clark, JRAI (Journal

of the Royal Archaeological Institute), vol. 88, Pt. 2, July-Dec.,

1958, p.133.

pg.8

of 23 pg.8

of 23

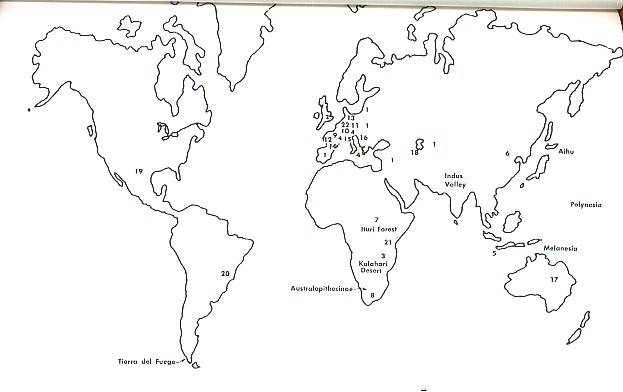

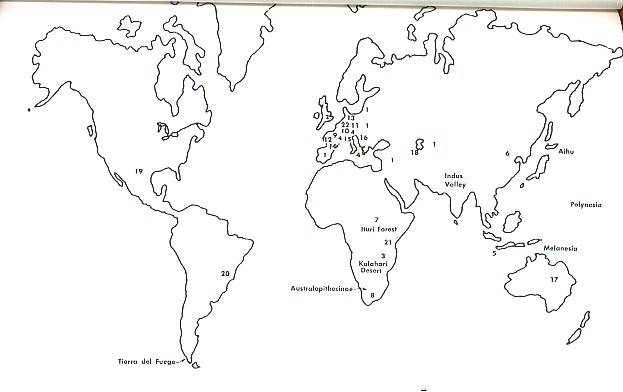

Fig. 3. The approximate locations of the

fossils remains or primitive peoples in this volume.

| 1. Neanderthal Man (in |

4. Cromagnon Man |

7. Kangera |

13. Obercassel |

19. Folsom |

| Palestine), M. es Skhul, |

5. Solo Man |

8. Florisbad |

14. La Chapelle |

20. Lagoa Santa |

| Mugharit-et-Tabun |

Pithecanthropus

erectus |

9. Fontechevade |

15. Grimaldi |

21. Olduvai |

| 2. Swanscombe Man, |

6. Pekin Man, |

10. Heidelberg |

16. Krapina |

22. Canstadt |

| Galley

Hill |

Sinanthropus

and |

11. Mauer Jaw |

17. Talgai |

|

| 3. Rhodesian Man |

Choukoutien |

12. La Quina Woman |

18. Hotu |

|

pg.9

of 23 pg.9

of 23

specialized races evolve."

According to Lebzelter, this is why racial differentiation was

relatively marked in the earlier stages of man's history. The

explanation of this fact is clear enough. In a very small closely

inbreeding population, genes for odd characters have a much better

chance of being homozygously expressed so that such characters

appear in the population with greater frequency, and tend to

be perpetuated. On the other hand, such a small population may

have so precarious an existence that the margin of survival is

too small to encourage or permit cultural diversities to find

expression. Thus physical type is variant but is accompanied

by cultural conformity, whereas in a large and well-established

community, a physical norm begins to appear as characteristic

of that population, but the security resulting from numbers allows

for a greater play of cultural divergence.

At the very beginning, we might

therefore expect to find in the central area a measure of physical

diversity and cultural uniformity: and at each secondary or provincial

centre in its initial stages, the same situation would reappear.

The physical diversity to be expected on the foregoing grounds,

would, it is now known, be exaggerated even further by the fact

(only comparatively recently recognized) that when any established

species enters a new environment it at once gives expression

to a new and greater power of diversification. Many years ago,

Sir William Dawson remarked upon this in both plant and animal

biology. (152)

From a study of post-Pliocene molluscs and other fossils, he

concluded that "new species tend rapidly to vary to the

utmost extent of their possible limits and then to remain stationary

for an indefinite time." An explanation of this has been

proposed recently by Colin H. Selby in the Christian Graduate.

(153) The circumstance

has been remarked upon also by Charles Brues, (154) who adds that "the variability of forms is slight

once the population is large, but at first is rapid and extensive

in the case of many insects for which we have the requisite data."

Further observations on this point were made by Adolph Schultz

in discussing primate populations in the 1950 Cold Springs Harbor

Symposium. (155)

152. Dawson, Sir William, The Story of

the Earth, Hodder and Stoughton, London, 1903, p.360.

153. Selby, Colin H., in a "Research Note," in the

Christian Graduate, IVF, London, 1956, p.99.

154. Brues, Charles, "Contribution of Entomology to Theoretical

Biology," Scientific Monthly, Feb., 1947, pp.123ff.,

quoted at p.130.

155. Schultz, Adolph, "The Origin and Evolution of Man,"

Cold Springs Harbor Symposium on Quantitative Biology,

1950, p.50.

pg.10

of 23 pg.10

of 23

Thus we have in reality three factors, all of which

are found to be still in operation in living populations, which

must have contributed to the marked variability of early fossil

remains particularly where several specimens are found in a single

site as at Choukoutien for example, or at Obercassel, or Mount

Carmel.

These factors may be summarized as follows:

(a) A new species is more variable when it first appears; (b) A smal1

population is more variable than a large one; (c) When a species or a

few members of it shift into a new environment, wide varieties again appear

which only become stable with time. To these should be added a fourth,

namely, that small populations are likely to be highly conservative in

their culture, thus maintaining many links though widely extended geographically.

Fossil remains constantly bear witness to

the reality of these factors, but this has meaning only if we assume that

a small population began at the centre and, as it became firmly established

there, sent out successive waves of migrants usually numbering very few

persons in any one group, who thereafter established a further succession

of centres, the process being repeated again and again until early rman

had spread into every habitable part of the world. Each new centre at

the first showed great diversity of physical type but as they multiplied

a greater uniformity was achieved in the course of tine. Where such a

subsidiary centre was wiped out before this uniformity had been achieved

but where their remains were preserved, the diversity was, at it were,

captured for our examination. At the same time, in marginal areas where

individuals or families were pushed by those who followed them, circumstances

often combined to degrade them physically so that fossil man tended toward

a bestial form -- but for secondary reasons. On the other hand, in the

earliest stages of these migrations cultural uniformity would not only

be the rule in each group but necessarily also between the groups. And

this, too, has been found to be so to a quite extraordinary degree. Indeed,

following the rule entunciated above, the most primitive groups -- those

which had been pushed furthest to the rim � might logically be expected

to have the greatest cultural uniformity, so that links would not be surprising

if found between such peripheral areas as the New World, Europe, Australia,

South Africa, and so forth, which is exactly what has been observed.

Such lines of evidence which we

shall explore a little further, force upon us the conclusion

that we should not look to these

pg.11

of 23 pg.11

of 23

marginal areas, to primitive

contemporaries or to fossil remains, for a picture of the initial

stages of man's cultural position. It is exactly in these marginal

areas that we shall not find them. The logic of this was

both evident to and flatly rejected by E. A. Hooten who remarked:

(156)

The adoption of such a principle

would necessitate the conclusion that the places where one finds

existing primitive forms of any order of animal are exactly in

the places where these animals could not have originated. . .

.

But this is the principle of lucus

a non lucendo, i.e., finding light just where one ought not

to do so, which pushed to its logical extreme would lead us to

seek for the birthplace of man in that area where there are no

traces of ancient man and none of any of his primate precursors

[my emphasis].

William Howells

has written at some length on the fact that, as he puts it, "all

the visible footsteps lead away from Asia.'' (157) He then examines the picture with respect to the

lines of migration taken by the "Whites" and surmises

that at the beginning they were entrenched in southwest Asia

"apparently with the Neanderthals to the north and west

of them." He proposes that while most of them made their

way into both Europe and North Africa, some of them may have

travelled east through central Asia into China, which would possibly

explain the Ainus and the Polynesians. He thinks that the situation

with respect to the Mongoloids is pretty straightforward, their

origin having been somewhere in the same area as the Whites,

whence they peopled the East. The dark skinned peoples are, as

he put it "a far more formidable puzzle." He thinks

that the Australian aborigines can be traced back as far as India,

with some evidence of them perhaps in southern Arabia. Presumably,

the African Negroes are to be derived also from the Middle East,

possibly reaching Africa by the Horn and therefore also via Arabia.

However, there are a number of black-skinned peoples who seem

scattered here and there in a way which he terms "the crowning

enigma," a major feature of which is the peculiar relationships

between the Negroes and the Negritos. Of these latter, he has

this to say: (158)

They are spotted among the Negroes

in the Congo Forest, and they turn up on the eastern fringe of

Asia (the Andaman Islands, the Malay Peninsula, probably India,

and possibly

156. Hooten, E. A., "Where Did Man Originate?"

Antiquity, June, 1927, p.149.

157. Howells, Wm., Mankind So Far, Doubleday Doran, 1945,

pp.295ff.

158. Ibid., pp.29S, 299.

pg.12

of 23 pg.12

of 23

formerly in southern China), in the

Philippines, and in New Guinea, and perhaps Australia, with probable

traces in Borneo, Celebes, and various Melanesian Islands.

All of these are "refuge"

areas, and undesirable backwoods which the Pygmies have obviously

occupied as later more powerful people arrived in the same regions.

. . .

Several things stand out from these

facts. The Negritos must have had a migration from a common point.

. . . And it is hopeless to assume that their point of origin

was at either end of their range. . . . It is much more likely

that they came from some point midway, which is Asia.

There is, then, a very

wide measure of agreement that the lines of migration radiate not from

a point somewhere in Africa, Europe, or the Far East, but from a geographical

area which is to be closely associated with that part of the world in

which not only does Scripture seem to say that man began peopling the

world after the Flood physically, but also where he began culturally.

Looking at the spread of civilization as we have looked at the spread

of people, it is clear that the lines follow the same course. The essential

difference, if we are taking note of current chronological sequences,

is that whereas the spread of people is held to have occurred hundreds

and hundreds of thousands of years ago, the spread of civilization is

an event which has taken place almost within historic times.

One might postulate that those

whose migration took place hundreds of thousands of years ago

and whose remains supply us with fossil man and prehistoric cultures

(Aurignacian, etc.) were one species; and that those who initiated

the basic culture in the Middle East area -- the watershed of

all subsequent historic cultures in the world -- were another

species. Some have tentatively proposed a concept such as this

by looking upon Neanderthal Man as an earlier species or subspecies

who was eliminated with the appearance of so-called "modern

man.'' (159) The

association of Neanderthals with moderns in the Mount Carmel

finds seems to stand against this conception. (160) And indeed, there is a very widespread agreement

today that, with the exception of the most recent South African

finds, al1 fossils, prehistoric, primitive, and modern men are

one species, Homo sapiens.

Ralph Linton viewed the varieties

of men revealed by fossil

159. Weidenreich, Franz von, Palaeontologia

Sinica, whole series No.127, 1943, p.276; and see F. Gaynor

Evans in Science, July, 1945, pp.16, 17.

160. Romer, Alfred, Man and the Vertebrates, University

of Chicago Press, 1948, pp.219, 221.

pg.13

of 23 pg.13

of 23

finds to be due to factors which

we have already outlined. As he put it: (161)

If we are correct in our belief that

all existing men belong to a single species, early man must have

been a generalized form with potentialities for evolving into

all the varieties which we know at present. It further seems

probable that this generalized form spread widely and rapidly

and that within a few thousand years of its appearance small

bands of individuals were scattered over most of the Old World.

These bands would find themselves in many

different environments, and the physical peculiarities which were advantageous

in one of these might be of no importance or actually deleterious in

another. Moreover, due to the relative isolation of these bands and

their habit of inbreeding, any mutation which was favorable or at least

not injurious under the particular circumstances would have the best

possible chance of spreading to all members of the group.

It seems quite possible to account

for all the known variations in our species on this basis, without

invoking the theory of a small number of distinct varieties.

Viewed in this

light, degraded fossil specimens found in marginal regions should

neither be treated as "unsuccessful" evolutionary experiments

towards the making of true Homo sapiens types, nor as "successful,"

but only partially complete phases or links between apes and

men. Indeed, as Griffith Taylor was willing to admit, (162) "the location of

such 'missing' links as Pithecanthropus in Java, etc., seemed

to have little bearing on the question of the human cradleland."

He might in fact also have said the same on the question of human

origins. He concludes, "They are almost certainly examples

of a . . . type which has been pushed out to the margins."

Thus the way in which one studies

or views these fossil remains is very largely coloured by one's

thinking whether it is in terms of biological or historical processes.

Prof. A. Portmann of Vienna remarked: (163)

One and the same piece of evidence

will assume totally different aspects according to the angle

-- palaeontological or historical -- from which we look at it.

We shall see it either as a link in one of the many evolutionary

series that the paleontologist seeks to establish, or as something

connected with remote

161. Linton, Ralph, The Study of Man,

Student's edition, Appleton, New York, 1936, p.26.

162. Taylor, Griffith, Environment, Race and Migration,

University of Toronto, 1945, p.282.

163. Portmann, A., "Das Ursprungsproblem," Eranos-Yahrbuch,

1947, p.11.

pg.14

of 23 pg.14

of 23

historical actions and developrnents

that we can hardly hope to reconstruct. Let me state clearly

that for my part I have not the slightest doubt that the remains

of early man known to us should all be judged historically.

This same approach

toward the meaning of fossil man has been explored in some detail

by Wilhelm Koppers who thinks that "primitiveness in the

sense of man being closer to the beast" can upon occasion

be the "result of a secondary development." (164) He believes that it would

be far more logical to "evolve" Neanderthal Man out

of Modern Man than Modern Man out of Neanderthal Man. He holds

that Neanderthal was a specialized and more primitive type, but

later than modern man, at least in so far as they occur in Europe.

Such a great authority as Franz von Weiderlreich

(165) was also prepared

to admit unequivocably, "no fossil type of man has been discovered

so far whose characteristic features may not easily be traced back to

modern man" [my emphasis]. This agrees with the opinion of Griffith

Taylor, (166) who observed,

"Evidence is indeed accumulating that the paleolithic folk of Europe

were much more closely akin to races now living on the periphery of the

Euro-African regions than was formerly admitted." Many years ago,

Sir William Dawson pursued this same theme and explored it at sorne length

in his beautifully written, but almost completely ignored work, Fossil

Man and Their Modern Representatives. Though at one time the unity

of man was questioned, we see that it was not questioned by all.

On almost every side we are now

being assured that the human race is, as Scripture says, "of

one blood," a unity which comprehends ancient and modern,

primitive and civilized, fossil and contemporary man. It is asserted

by Ernst Mayr, (167)

by Melville Herskovits, (168) by W. M. Krogman, (169) by Leslie White, (170)

164. Koppers, W., Primitive Man and His

World Picture, Sheed and Ward, New York, 1952, pp.220, 224.

165. Weidenreich, Franz von, Apes, Giants and Man, University

of Chicago Press, 1948, p.2.

166. T'aylor, Griffith, Environment, Race and Migration, University

of Toronto, 1945, pp.46, 47.

167. Mayr, Ernst, "The Taxonomic Categories in Fossil Hominids,"

Cold SpringsHarbor Symposium, vol15, 1950, p.117.

168. Herskovits, Melville, Man and His Works, Knopf, New

York, 1950, p.103.

169. Krogman, W. M., ''What We Do Not Krow About Race,"

Scientific Monthly, Aug., 1943, p.97, and subsequently,

Apr., 1948, p.317.

170. White, Leslie, "Man's Control over Civilization: An

Anthropocentric Illusion," Scientific Monthly, Mar.,

1948, p.238.

pg.15

of 23 pg.15

of 23

by A. V. Carlson, (171) by Robert Redfield, (172) and indeed by UNESCO.

(173) At the Cold

Springs Harbor Symposium on "Quantitative Biology"

held in 1950, T. D. Stewart, (174) in a paper entitled, "Earliest Representatives

of Homo Sapiens," stated his conclusions in the following

words, "Like Dobzhansky, therefore, I can see no reason

at present to suppose that more than a single hominid species

has existed on any time level in the Pleistocene." Alfred

Romer (175) observed

in commenting on the collection of fossil finds from Palestine

(Mugharet-et-Tabun, and Mugharetes-Skubl), "While certain

of the skulls are clearly Neanderthal, others show to a variable

degree numerous neanthropic (i.e., "modern man") features."

Subsequently he identifies such neanthropic skulls as being of

the general Cro-Magnon type in Europe �- a type of man who

appears to have been a splendid physical specimen. He proposes

later that the Mount Carmel people "may be considered as

due to interbreeding of the dominant race (Cro-Magnon Man) with

its lowly predecessors (Neanderthal Man)." Thus the picture

which we once had of ape-like half-men walking with a stooped

posture, long antedating the appearance of "true" Man,

has all been changed with the accumulation of evidence. These

stooped creatures now are known to have walked fully erect, (176) their cranial capacity

usually exceeding that of modern man in Europe (if this means

anything); and they lived side by side with the finest race (physically

speaking) which the world has probably ever seen.

As an extraordinary example of

the tremendous variability which an early, small isolated population

can show, one cannot do better than refer to the finds at Choukoutien

in China, (177)

from the same locality in which the famous Pekin Man was

171. Carlson, A. V., in his retiring address

as President of the American Association of Advanced Science,

Science, vol.103, 1946, p.380.

172. Redfield, Robert, "What We Do Know About Race,"

Scientific Monthly, Sept., 1943, p.193.

173. UNESCO: Provisional draft: given as of May 21st, 1952, in

Man, Royal Anthropological Institute, June, 1952,

p.90.

174. Stewart, T. D., "Earliest Representatives of Homo sapiens",

Cold Springs Harbor Symposium, vol.15, 1950, p.105.

175. Romer, Alfred, Man and the Vertebrates, University

of Chicago Press, 1948, pp.219, 221.

176. Neanderthal erect: first reported by Sergio Sergi in Science,

supplement 90, 1939, p.13; contrast with M. C. Cole, The Story

of Man, Chicago, 1940, frontispiece facing p.13: and note

that Cole's reconstruction of a stooped Neanderthal, for popular

consumption, appeared one year later than the report in Science.

177. For a useful and early summary report, see "Homo sapiens

at Choukoutien," News and Notes, Antiquity, June,

1939, p.242.

pg.16

of 23 pg.16

of 23

found. These fossil

remains came from what is known as the Upper Cave, consisting

of seven individuals, who appear to be members of one family:

an old man judged to be over 60, a younger man, two relatively

young women, an adolescent, a child of five, and a newborn baby.

With them were found implements, ornaments, and thousands of

fragments of animals.

Study of these remains has produced

some remarkably interesting facts. The most important in the

present context is that, judged by cranial form, we have in this

one family a representative Neanderthal Man, a "Melanesian"

woman who reminds us of the Ainu, a Mongolian type, and another

who is rather similar to the modern Eskimo woman. In commenting

on these finds Weidenreich expressed his amazement at the range

of variation: (178)

The surprising fact is not the

occurrence of paleolithic types of modern man which resemble

racial types of today, but their assemblage in one place and

even in a single family, considering that these types are found

today settled in far remote regions.

Forms similar to that of the "Old

Man" as he has been named, have been found in Upper Paleolithic,

western Europe and northern Africa; those closely resembling

the Melanesian type, in the neolithic of Indo-China, among the

ancient skulls from the Cave of Lagoa Santa in Brazil, and in

the Melanesian population of today; those closely resembling

the Eskimo type occur among the pre-Columbian Amerindians of

Mexico and other places in North America, and among the Eskimos

of western Greenland of today.

Weidenreich then proceeds

to point out subsequently that the upper Paleolithic melting-pot of Choukoutien

"does not stand alone.'' (179)

In Obercassel in the Rhine Valley were found two skeletons, an old male

and a younger female, in a tomb of about the same period as the burial

in Choukoutien. He says, "The skulls are so different in appearance

that one would not hesitate to assign them to two races if they came from

separate localities." So confused is the picture now presented that

he observes: (180)

Physical anthropologists have

gotten into a blind alley so far as the definition and the range

of individual human races and their history is concerned. . .

.

But one cannot push aside a whole

problem because the methods applied and accepted as historically

sacred have gone awry.

178. Weidenreich, F., Apes, Giants, and Man., University

of Chicago Press, 1948, p.87.

179. Ibid., p.88.

180. Ibid.

pg.17

of 23 pg.17

of 23

This extraordinary variability nevertheless still

permits the establishment of lines of relationshlip which appear

to crisscross in every direction as a dense network of evidence

that these fossil remains for the most part belong to a single

family.

Griffith Taylor links together Melanesians,

Negroes, and American Indians. (181)

The same authority proposes a relationship between Java Man and Rhodesian

Man. (182) He relates certain

Swiss tribes which seem to be a pocket of an older racial stock with the

people of northern China, the Sudanese, the Bushmen of South Africa, and

the Aeta of the Plilippines. (183)

He would also link the Prednost Skull to Aurignacian folk and to the Australoids.

(184) Macgowan (185)

and Montagu (186) are convinced

that the aboriginal populations of central and southern America contain

an element of Negroid as well as Australoid people. Grimaldi Man is almost

universally admitted to have been Negroid even though his remains lie

in Europe, (187) and indeed

so widespread is the Negroid type that even Pithecanthropus erectus was

identifed as Negroid by Buyssens.(188)

Huxley maintained that the Neanderthal

race must be closely linked with the Australian aborigines, particularly

from the Province of Victoria; (189) and other authorities hold that the same Australian

people are to be related to the famouls Canstadt Race. (190) Alfred Romer relates

Solo Man from Java with Rhodesian Man from Africa. (191) Hrdlicka likewise relates

the Oldoway Skull with LaQuina Woman; LaChapelle and others to

the basic African stock, (192) and holds that they must also be related to

181. Taylor, Griffith, Environment, Race

and Migration, University of Toronto, 1945, p.11.

182. Ibid., p.60. His argument here is based on head form,

which he considers conclusive.

183. Ibid., p.67. He feels only a "common cradle-land"

can possibly explain the situation.

184. Ibid., p.134.

185. Macgowan, K, Early Man in the New World, Macmillan,

New York, 1950, p.26.

186. Montagu, Ashley, Introduction to Physical Anthropology,

Thomas, Springfield, Illinois, 1947, p.113.

187. Weidenreich, Franz, Apes, Giants, and Man, University

of Chicago Press, 1948, p.88.

188. Buyssens, Paul, Les Trois Races de Europe et du Monde,

Brussels, 1936. See G. Grant McCurdy, American Journal of Archaeology,

Jan.-Mar., 1937, p.154.

l89. Huxley, Thormas, quoted by D. Garth Whitney, "Primeval

Man in Belgiurn," Transactions of the Victoria Institute,

vol.40,1908, p.38.

190. According to Whitney, see above, p.38.

191. Romer, Alfred, Man and the Vertebrates, University

of Chicago Press, 1948, p.223.

192. Hrdlicka, Ales, "Skeletal Remains of Early Man,"

Smithsonian Institute, Miscellaneous Collections, vol.83,

1930, p.342f'f.

pg.18

of 23 pg.18

of 23

Indian, Eskimo and Australian

races. Even the Mauer Jaw is held to be Eskimo in type. (193)

We cannot do better than sum up

this general picture in the words of Sir William Dawson who,

far in advance of his time, wrote in 1874: (194)

What precise relationship do

these primitive Europeans bear to one another? We can only say

that all seem to indicate one basic stock, and this is allied

to the Hamitic stock of northern Asia which has its outlying

branches to this day both in America and in Europe.

While it is perfectly true

that the thesis we are presenting has, in the matter of chronology, the

whole weight of scientific opinon against it, it is nevertheless equally

true that the interpretation of the data in this fashion makes wonderful

sense and, indeed, would have allowed one to predict both the existence

of widespread physical relationships as well as an exceptional variableness

within the members of any one family. In addition to these physiological

linkages there are, of course, a very great many cultural linkages. As

a single example the painting of the bones of the deceased with red ochre,

a custom which not so very long ago was still being practiced by the American

Indians, has been observed in prehistoric burials in almost every part

of the world. Surely such a custom could hardly arise everywhere indigenously

on some such supposition as that "men's minds work everywhere pretty

much the same. . . ." It seems much more reasonable to assume it

was spread by people wlo carried it with them as they radiated rapidly

from some central point.

This brings us once more to the question

of the geographical position of this Cradle. Evidence accumulates daily

that as a cultured being the place of man's origin was somewhere in the

Middle East. No other region in the world is as likely to have been the

Home of Man, if by man we mean something more than merely an intelligent

ape. Vavilov (195) and others

(196) have repeatedly pointed

out that the great majority of the cultivated

193. Ibid., p.98. And see William S.

Laughton, "Eskimos and Aleuts: Their Origins and Evolution,"

Science, vol.142, 1963, p.639, 642.

194. Dawson, Sir William, "Primitive Man," Transactions

of the Victoria Institute, London, vol.8, 1874, p.60-61.

195. Vavilov, N. I., "Asia, the Source of species",

Asia, Feb., 1937 p.113.

196. Cf. Harlan, J. R., "New World Crop Plants in Asia Minor,"

Scientific Monthly, Feb., 1951, p.87.

pg.19

of 23 pg.19

of 23

plants of the world,

especially the cereals, trace their origin there. Henry Field

remarks: (197)

Iran may prove to have been

one of the nurseries of Homo sapiens. During the middle or upper

Paleolitllic periods the climate, flora, and fauna of the Iranian

Plateau provided an environment suitable for human occupation.

Indeed, Ellsworth Huntington has postulated that during late

Pleistocene times southern Iran was the only [his emphasis]

region in which temperature and humidity were ideal, not only

for human conception and fertility but also for chances of survival.

Many speculations

exist as to the routes taken by Caucasoids, Negroids, and Mongoloids,

as the world was peopled by the successive ebb and flow of migrations.

Howells, (198)

Braidwood, (199)

Taylor, (200) Goldenweiser,

(201) Engberg,

(202) Weidenreich,

(203) Cole, (204) and others, (205) have tackled the problem

or have expressed opinions based on the study of fossil remains;

and of course, Coon's Races of Europe is largely concerned

with the same problem. (206) Not one of these can really establish how man originated,

but almost all of them make the basic assumption that western

Asia is his original home as a creature of culture. From this

centre one can trace the movements of an early migration of Negroid

people followed by Caucasoid people in Europe. From this same

area undoubtedly there passed out into the East and the New World

successive waves of Mongoloid people. In Africa Wendell Phillips,

(207) after studying

the relationships of various African tribes, concluded that evidence

already existed making it possible to derive certain of the tribes

from a

197. Field, Henry, "The Iranian Plateau

Race," Asia, Apr., 1940, p.217.

198. Howells, Wm., Mankind So Far, Doubleday Doran, New

York, 1945, pp.192, 203, 209, 228, 234, 238, 247, 289, and 290.

199. Braidwood, Robert, Prehistoric Man, Natural History

Museum, Chicago, 1948, pp.96, 106.

200. Taylor, Griffith, Environment, Races and Migration,

University of Toronto, 1945, pp.88, 115, 123, 164, and 268.

201. Goldenweiser, Alexander, Anthropology, Crofts, New

York, 1945, pp.427, 492.

202. Engberg, Martin, Dawn of Civilization, University

of Knowledge Series, Chicago, 1938, p.154.

203. Weidenreich, Franz von, Apes, Giants, and Man, University

of Chiccago Press, 1948, p.65.

204. Cole, M. C., The Story of Man, University of Knowledge

Series, Chicago, 1940.

205. See, for example, Boule, M. and H. V. Vallois, Fossil

Man, Dryden Press, New York, 1957, pp.516-522, an evaluation

of various views.

206. Coon, C. S., The Races of Europe, macMillan, 1939,

see especially Chapter 5.

207. Phillips, Wendell, "Further African Studies,"

Scientific Monthly, Mar., 1950, p.175.

pg.20

of 23 pg.20

of 23

single racial stock

(particularly the Pygmies of the Ituri Forest and the Bushmen

of the Kalahari Desert), which at a certain time must have populated

a larger part of the African continent only to retreat to less

hospitable regions as later Negroid tribes arrived in the country.

Prof. H. J. Fleure held that evidence of similar nature towards

the north and northeast of Asia and on into the New World was

to be discerned by a study in the change of head forms in fossil

remains. (208)

Wherever tradition is clear on the matter, it invariably points

in the same direction and tells the same story.

Thus we conclude that from the

family of Noah have sprung all the peoples of the world -- prehistoric,

protohistoric, and historic. And the events described in connection

with Genesis 10 and the prophetic statements of Noah with respect

to the future of his three sons together combine to provide us

with the most reasonable account of the early history of mankind,

a history which, rightly understood, does not at all require

us to believe that man began with the stature of an ape and only

reached a civilized state after a long, long evolutionary history.

In summary,

then, what we have endeavoured to show in this chapter is as

follows:

(1) The geographical distribution

of fossil remains is such that they are most logically explained

by treating them as marginal representatives of a widespread

and in part forced dispersion of people from a single multiplying

population established at a point more or less central to them

all, and sending forth successive waves of migrants, each wave

driving the previous one further toward the periphery;

(2) The most degraded specimens

are those representatives of this general movement who were driven

into the least hospitable areas, where they suffered physical

degeneration as a consequence of the circumstances in which they

were forced to live;

(3) The extraordinary physical

variability of fossil remains results from the fact that the

movements took place in small, isolated, strongly inbred bands;

but the cultural similarities which link together even the most

widely dispersed of them indicate a common origin for them all;

(4) What I have said to be true

of fossil man is equally true of living primitive societies as

well as those which are now extinct;

208. Fleure, H. J., The Races of Mankind,

Benn, London, 1930, pp.43, 44.

pg.21

of 23 pg.21

of 23

(5) All the initially

dispersed populations are of one basic stock -- the Hamitic family

of Genesis 10;

(6) The initial Hamitic settlers

were subsequently displaced or overwhelmed by Indo-Europeans

(i.e., Japhethites), who nevertheless inherited, or adopted,

and extensively built upon Hamitic technology and so gained an

advantage in each geographical area where they spread;

(7) Throughout the great movements

of people, both in prehistoric and historic times, there were

never any human beings who did not belong within tle family of

Noah and his descendants;

(8) Finally, this thesis is strengthened

by the evidence of history which shows that migration has always tended

to follow this pattern, has frequently been accompanied by instances of

degeneration both of individuals or whole tribes, usually resulting in

the establishment of a general pattern of cultural relationships which

parallel those archaeology has revealed.

The tenth clapter of Genesis

stands between two passages of Scripture to which it is related in such

a way as to shed light on both of them. In the first, Genesis 9:20�27,

we are given an insight into the relationship of the descendants of the

three sons of Noah throughout subsequent history, Ham doing great service,

Japhet being enlarged, and Shem's originally appointed place of responsibility

being ultimately assigned to Japheth. We are not told here the nature

of Ham's service, nor how Japheth would be enlarged nor what special position

Shem was ultimately to surrender to his brother. In the second passage,

Genesis 11:1�9, we are told that there was but a single language spoken

by all men until a plan was proposed that led to the dramatic scattering

of the planners over the whole earth.

In the centre stands Genesis 10, supplying

us with vital clues to the understanding of these things by tclling us

exactly who the descendants were of each of these three sons. With this

clue, and with the knowledge of history which we now have, we can see

the significance of both passages. We now understand in what way Ham became

a servant of his brethren, in what way Japheth's spread over the earth

could be called an enlargement rather than a scattering, and in what circumstances

Shem has surrendered his position of special privilege and responsibility

to Japheth. We could not fully perceive how these prophetic statements

had been fulfilled without our knowledge of who

pg.22

of 23 pg.22

of 23

among the nations were

Hamites and who were Japhethites. And this knowledge we derive

entirely from Genesis 10.

Furthermore, the real significance

of the events which surrounded and stemmed from the abortive

plan to build the Tower of Babel would similarly be lost to us

except for the knowledge that it was Ham's descendants who paid

the penalty. This penalty led to their being scattered very early

and forced them to pioneer the way in opening up the world for

human habitation, a service which they rendered with remarkable

success but no small initial cost to themselves.

Moreover, if we consider the matter

carefully, we shall perceive also the great wisdom of God who,

in order to preserve and perfect His revelation of Himself, never

permitted the Shemites to stray far from the original cultural

centre in order that He might specially prepare one branch of

the family to carry this Light to the world as soon as the world

was able to receive it. For it is a principle recognized in the

New Testament by our Lord when He fed the multitudes before He

preached to them and borne out time and again in history, that

spiritual truth is not well comprehended by men whose struggle

merely to survive occupies all their energies.

Thus where Ham pioneered and opened

up the world to human occupation, Japheth followed at a more

leisurely pace to consolidate and make more secure the initial

"dominion" thus achieved. And then -- and only then

-- was the world able and prepared to receive the Light that

was to enlighten the Gentiles and to cover the earth with the

knowledge of God as the waters cover the sea.

Footnote on the time taken for early migrations.

Kenneth Macgowan shows that with respect

to a Middle East "Cradle of Man," the most distant settlement

is that in the very southern tip of South America, 15,000 miles approximately.

How long would such a trip take? He says that it has been estimated that

men might have covered the 4000 miles from Harbin, Manchuria, to Vancouver

Island, in as little as 90 years (Early Man in the New World, Macmillan,

1950, p.3 and rnap on p.4) .

What about the rest of the distance

southward? Alfred Kidder says, "A hunting pattern based

primarily on big game could have carried man to southern South

America without the necessity at that time of great localized

adaptation. It could have been effected with relative rapidity,

so long as camel, horse, sloth, and elephant were available.

All the indications point to the fact that they were." (Appraisal

of Anthropology Today, University of Chicago Press, 1953,

p.46.)

pg.23

of 23 pg.23

of 23  Copyright © 1988 Evelyn White. All rights

reserved

Previous Chapter *

End of Part II * Next

Chapter (Part III)

Copyright © 1988 Evelyn White. All rights

reserved

Previous Chapter *

End of Part II * Next

Chapter (Part III)

|