|

Abstract

Table of Contents

Part I

Part II

Part III

Part IV

Part V

|

Vol.1: Noah's Three Sons: Human History

in Three Dimensions

PART III

WHY NOAH CURSED CANAAN INSTEAD

OF HAM:

A NEW APPROACH TO AN OLD PROBLEM

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Chapter 1. Why Noah Cursed

Canaan

Chapter 2. Was Canaan a True Black?

Publishing History:

1957 Doorway paper No. 55, published

privately by Arthur C. Custance

1975 Part III in Noah's Three Sons: Human History in

Three Dimensions, vol.1 in The Doorway Papers Series,

1997 Arthur Custance Online Library (html)

2001 2nd Online Edition (corrections, design revisions)

pg

1 of 11 pg

1 of 11

A NOTE TO THE READER

THIS next paper is

very short. Yet there are some points of importance to consider

in the light of it.

It shows how

necessary it sometimes is to be able to escape one's own culture

and enter into the spirit of another culture that is structured

differently, in order to see the real motives which lie behind

even our own judgments at times.

It also shows

that the great figures of old, heroic though they may seem to

have been, were very ordinary mortals really! This assumes, of

course, that our interpretation is correct.

Another lesson

is that each correction of some fundamental untruth is itself

in time distorted until it too becomes untrue.

And finally,

it demonstrates how wonderfully Scripture holds together with

an inner concordance that still renders it its own best interpreter.

pg.2

of 11 pg.2

of 11

Chapter 1

Why Noah Cursed Canaan

And Noah began to be an husbandman,

and he

planted a vineyard:

And he drank of the wine, and was drunken;

and he

was uncovered within his tent.

And Ham, the father of Canaan, saw the

nakedness

of his father, and told his two brethren without.

And Shem and Japheth took a garment,

and laid it upon

both their shoulders, and went backward, and covered the nakedness

of their father; and their faces were backward, and they saw

not their father's nakedness.

And Noah awoke from his wine, and knew

what his younger

son had done unto him.

And he said, Cursed be Canaan; a servant

of servants shall he be unto his brethren.

And he said, Blessed be the LORD

God of Shern; and Canaan

shall be his servant.

God shall enlarge Japheth, and he shall

dwell in the tents of Shem; and Canaan shall be his servant.

THE STORY appears

in Genesis 9:20-27. Noah, apparently, cultivated a vineyard and

whether intentionally or accidentally ended up with an intoxicating

drink. Like many others in this condition, he had removed his

clothes because of the sensation of overheating which results

from the dilation of the veins at the surface of the skin. Drunkenness

and nakedness have been closely associated throughout history.

In a drunken stupor the old man lay indecently exposed and his

son Ham "saw his nakedness" (verse 22) .

Some people believe that this phrase

means more than appears on the surface and that on the basis

of Leviticus chapters 18 and 19, the implication is that homosexuality

was involved. On the other hand, Ham's immediate behaviour seems

to tell against this, for he would hardly proceed to tell his

two

pg.3

of 11 pg.3

of 11

brothers outside (verse

22) if he had committed such a terrible offense against his father.

Moreover, the behaviour of Shem and Japhetd in taking a garment

and carefully covering the nakedness of their father with their

faces averted so that "they saw not their father's nakedness''

(verse 23 suggests that in both instances the words mean simply

what they say.

Later on, Noah awoke and somehow

found out what his younger son had done. Like many others who

have lost their own self-esteem and are angry at themselves,

Noah became enraged against his son. But he did not curse him;

he cursed his grandson according to verse 25. And herein seems

to, lie the injustice, and the widespread conviction that the

text is in error. Shem and Japheth are blessed, Ham is ignored

and a grandson, Canaan, who can surely have had no responsible

part in Ham's misbehaviour, suffers the full brunt of his grandfather's

anger. (1)

Several explanations have been

offered as to why, when Noah had thus been wronged by Ham, he

pronounced a curse upon Canaan instead. I should like to suggest

a reason which seems to have been overlooked.

In Exodus 20:5, God declared that

He would "visit the iniquities of the fathers upon the children

unto the third and fourth generations. . . ." There is nothing

arbitrary, barbaric, or even surprising about this. The sins

of the fathers are reflected in the behaviour of their children,

and these children in their turn pay the penalty. What is surprising,

however, is that men will distort the truth and make it a falsehood

of the most malicious kind. It soon comes to mean that a child

is not to be blamed for his sins - his environment and his heredity

being held chiefly responsible.We say easily enough, "It

is our fathers who are to be blamed, the generation which educated

us. We are simply the children of our own age." Thus, even

today a more sympathetic view is being taken of Adolf Hitler

and some would even try to picture him as a child who was wronged

and might otherwise have been a hero. And in any case he is not

to be blamed for what he did.

Curiously enough, this inverted

process of reasoning is exactly what the Israelites applied to

Exodus 20:5. By the time of Jeremiah they were saying, "The

fathers have eaten sour

1. Paul Hershon, in his Rabbinical Commentary

on Genesis (Hodder and Stoughton, 1885, p.54) quotes a passage

in which the child Canaan is said to have first seen Noah uncovered,

and then to have told his father Ham about it.

pg.4

of 11 pg.4

of 11

grapes and the children's

teeth are set on edge" (Jeremiah 31: 29) . In other words,

it was not the children's misdoings which had brought all these

misfortunes upon them. It was all their fathers' fault! But the

Lord said in effect to Jeremiah, "You must correct this;

it is quite wrong. Tell them that 'every one shall die for his

own sin; every man that eateth sour grapes, his own teeth

shall be set on edge'" (Jeremiah 31:30).

It might be thought that this would

have settled the matter and straightened things out once for

all. But in the course of time, the truth was again distorted

in another way and people came to interpret this to mean that

any misfortune which overtook a man was due to his own sinfulness.

Not unnaturally, this had the effect of destroying all sympathy,

for a man who was in trouble or sickness was simply receiving

his just deserts. It served him right.

This is what created the peculiar

problem for the disciples when they were brought face to face

with a man born blind in John 9:1ff. It seems doubtful if it

was sympathy that made them question the Lord about his case,

but rather a kind of theological curiosity. Here was a man who

had suffered a great misfortune. He had been born blind. But

since he was born blind, it seemed impossible to attribute

the fault to the man himself. On the other hand, Jeremiah had

made it clear that Exodus 20:5 did not mean that it was his parents'

fault. So they asked, "Who did sin, this man or his parents?"

Their question reflected their attitude towards suffering. The

Lord, however, while not denying the truth of the implications

in their question, nevertheless pointed out that in this instance

the blind man was a privileged person who providentially was

permitted to show forth the glory of God. There are at least

three reasons why people suffer: because of the wickedness of

their parents, because of their own sinfulness, or simply for

the glory of God.

Now, in other cultures than our

own, and for reasons which are not always clear, it is customary

to attach the blame for a man's failings upon his parents. But

by the same token, it is also customary to give them the credit

for his successes. This principle is recognized by most of us,

in fact, but mostly without explicit formulation. In these other

cultures, both ancient and modern, the principle has been publicly

recognized.

It is an attitude which is quite

remarkably reflected in Scripture. Perhaps the clearest illustration

is to be found in the story of Saul and David, I Samuel 17: 50-58.

In this instance,

pg.5

of 11 pg.5

of 11

David had performed a

deed of great national importance by destroying Goliath. David

himself was no stranger to Saul for he had on many occasions

played his harp to quiet the king's distracted spirit. Yet we

find that when Saul saw David go forth against Goliath (verse

55) he said to Abner, the captain of his hosts, "Abner,

whose son is this youth?" And although Abner must certainly

have known David by name, he replied, "As thy soul liveth,

O King, I cannot tell."

This has always seemed a strange

remark both for the king and his commanding officer to have made.

But the explanation lies in a proper understanding of the social

significance of verse 58. "And Saul said unto him, Whose

son art thou, young man? And David answered, I am the son of

thy servant Jesse, the Bethlehemite." This is simply an

occasion upon which, following the social custom of his own day,

Saul sought to give credit where credit was due, namely, to the

father. Because David was Jesse's son, Jesse was to receive recognition.

Another illustration will be found

in I Kings 11:9-12:

And the Lord was angry with

Solomon, because his heart was turned from the Lord God of Israel

which had appeared unto him twice, and had commanded him concerning

this thing, that he should not go after other gods: but he kept

not that which the Lord commanded.

Wherefore the Lord said unto Solomon,

Forasmuch as this is done of thee and thou hast not kept my covenant

and my statutes, which I have commanded thee, I will surely rend

the kingdom from thee and will give it to thy servant.

Notwithstanding in thy days I will

not do it for David thy father's sake: but I will rend it out

of the hand of thy son.

This is a beautiful

example, because it is so specific in statement. Solomon was

to be punished: but he could not be punished personally without

bringing discredit on David his father, and this the Lord was

not willing to do. The only way in which Solomon could be punished

appropriately without injuring David's name was therefore to

punish Solomon's son.

In the New Testament we find another

instance. It is quite obvious that while a man can publicly seek

to give credit to the father of a worthy son, a woman could not

discreetly make reference to the father in complimentary terms

for fear of being misunderstood. She therefore refers instead

to the son's mother who rightly shares in the worthiness of her

children. This fact is reflected clearly in Luke 11:27, where

we read of a woman who suddenly perceiving the true greatness

of the Lord Jesus

pg.6

of 11 pg.6

of 11

Christ, cried out in spontaneous

admiration, "Blessed is the womb that bare Thee and the

breasts which Thou hast sucked."

When we apply this principle to

the story given in Genesis 9:20-97, the significance of the cursing

of Canaan rather than Ham at once becomes clear. But because

the principle has not been applied by commentators, the apparent

injustice of Noah has puzzled people at least since the beginning

of the Christian era when the commentators began to take notice

of it. It appears that Jewish rabbis had access to a copy of

the Septuagint (the Greek translation of the Old Testament, made

in the third century B.C. by the Jews in Alexandria and which

appears to form the basis of a number of quotations in the New

Testament from the Old Testament) in which the name "Canaan"

was replaced by the name "Ham.'' It is proposed by some

authorities that this was the original reading and that the text

was tampered with by Hebrew scribes who wished to add to the

degradation of the Canaanites by showing that they were the subjects

of a divine curse.

However, it is quite possible to

explain the text exactly as it is, as a reflection of the social

custom which we have been considering above. To begin with, there

may have been a reason for Ham's behaviour, other than mere disrespectfulness.

Without becoming involved in the

technicalities of genetics, it is possible that Ham may himself

have been a mulatto. in fact, his name means "dark"

and perhaps refers to the colour of his skin. This condition

may have been derived through his mother, Noah's wife, and if

we suppose that Ham had himself married a mulatto woman, it is

possible to account for the preservation of the negroid stock

over the disaster of the Flood. (2) It seems most likely that Ham had seen the darkness

of his mother's body, for example when being nursed. But he may

never have seen the whiteness of his father's body.

When Charles Darwin visited the

Tierra del Fuegans during the Voyage of the Beagle, he remarks

how interested the natives were in the colour of his skin. Naturally

his face and his hands were bronzed by exposure to the weather

after the long voyage, but when he rolled up a sleeve and bared

his arm, to use his own words, "they expressed the liveliest

surprise and admiration at its whiteness."

(3)

2. See Chapter 2.

3. The Darwin Reader, Scribners, New York, 1956, extract

dated as of Dec. 17, 1832, paragraph 10.

pg.7

of 11 pg.7

of 11

The

same may have been true in the case of Ham and his father. His

own body and that of Noah's wife being quite dark, he may have

gone away reflecting upon the difference and forgetting his filial

duty. In fact, this could conceivably be the reason he went to

tell his brothers, for he may have supposed that they would be

as surprised at this discovery as he was himself.

If this was the case, it may be

argued that this was a small offense to receive such a pronounced

judgment. But it is not at all certain that the form of the curse

was as severe as it appears to be. That his posterity were to

be servants, yes -- but the Hebrew can just as readily be translated

"servants par excellence." This actually is more likely,

for we have in Hebrew plenty of instances of the superlatively

excellent expressed in this manner, involving the reduplication

of the key word as "Holy of holies," "Lord of

Lords," etc. But where we find in Hebrew a comparable phrase

in which the author is referring to that which is superlatively

base (as in Daniel 4:17), the Hebrew uses an entirely different

form of construction. In other words, wherever Hebrew employs

a reduplication of a word, the concept intended is one of "excellence,"

much as in English we may say "very, very good." But

while we may also say "very, very bad," the Hebrew

evidently does not adopt this, but depends upon another form

of construction. In short, what we are saying is that the phrase

''servant of servants" may have meant that his descendants

would perform a great service to their brethren. The judgment,

in so far as it was a judgment, lies in the fact that they rendered

this service to others and bcnefitted little themselves.

However, the point is not essential

to this essay, and in any case, it is the subject of two extended

studies appearing as other Doorway Papers. (5) What is important to note is that Noah could not

pronounce judgment of any kind upon his own son, Ham, the actual

offender, without passing judgment upon himself, for society

held him, the father, responsible for his son's behaviour.

4. Compare: God of Gods (Daniel 2:47); Holy

of Holies (Hebrews 9:3); King of Kings (Revelation 19:16); Heaven

of Heavens (Nehemiah 9:6); Hebrew of Hebrews (Philippians 3:5);

Lord of Lords (Revelation 19:16); Song of Songs (Song of Solomon

1:1); Age of Ages (Ephesians 3:21). Note: the references in the

New Testament are either quotations from the Old Testament, or

are Hebrew thoughts expressed in Greek. In any case, it is clear

that the highest, not the lowest, is intended by the writer.

5. Custance, Arthur, Part

I, "The Part Played by Shem, Ham and Japheth in Subsequent

World History" and Part

IV, "The Technology of the Hamitic People", both

in Noah's Three Sons: History in Three Dimensions, vol.1

in The Doorway Papers Series.

pg.8

of 11 pg.8

of 11

To punish Ham, then, he

must of necessity pronounce a curse upon Canaan, Ham's son.

On the other hand, when it came

to blessing, the situation was very different. In pronouncing

a benediction upon Shem and Japheth, he was, in fact, doing himself

an honour! Such is human nature - and such is probably the explanation

of this otherwise puzzling incident.

pg.9

of 11 pg.9

of 11

Chapter 2

Was Cannan a True Black ?

LIKE SOME other

parts of this Paper, this appendix is also speculative. As long

as this is clearly understood, no harm will be done, provided

the speculation is not divorced entirely from the evidence. The

general title of these Doorway Papers was intended to suggest

that they could provide room for new approaches to old problems.

No one has ever suggested, to my

knowledge, that the Sumerians were negroid -- nor do any of the

reconstructed "Sumerian Life and Times" series such

as have appeared in the National Geographical Magazine,

or Life, ever so portray them. Yet there is some evidence

to suggest that they may have been black skinned.

According to Samuel Kramer (From

the Tablets of Sumer, Falcon's Wing Press, 1956, p.60), they

refer to themselves as "the blackheaded people." Actually

the Sumerian original reads "head-of-black people,"

the symbol for head (SAG) being a cone shaped hat hiding all

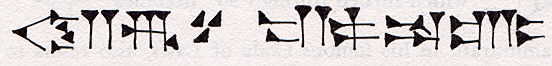

but the neck of the wearer, thus:

which turned through

90° becomes which turned through

90° becomes

Hammurabi in his famous Code of Laws, also refers to the

natives of Mesopotamia (Deimel's transcription, 1930, R. 94,

line 11) as:

A-NA SALMAT GAGGADIM

A-NA SALMAT GAGGADIM

i.e., "blackheaded ones."

Such descriptive

phrases are, I think usually taken to mean

pg.10

of 11 pg.10

of 11

merely "dark-haired."

But it seems likely that 95% or more of all the people who made

up the early Middle East cultures were black-haired, whether

Semitic or Sumerian, and the feature was hardly a distinguishing

one. lndo-Europeans (from Japheth, whose name possibly means

"fair") played little part in it till much later. But

the Semitic population according to A. H. Sayce (Fresh Light

from the Ancient Monuments, London, 1893, p.26) distinguished

themselves with racial pride from other peoples by their own

light coloured skin, and claimed that Adam too was a white man.

They were his racial descendants. Yet they had black hair like

the Sumerians and would not be different in this feature, and

might therefore just as well have been termed ''blackheaded people."

But they apparently never were.

Evidently, then, it would

be no mark of distinction to refer to the hair colour, but it

would definitely be such to refer to skin colour. And the Sumerians

were apparently proud of their black skin. In his Sumerian

Reader, Gadd says they came to equate the term "blackheaded

people" with the idea of "men" as real people

by contrast with other human beings who are not really men at

all.

It is further to be noted that

the founders of the wonderful Indus Valley cultures were black

skinned, and not merely black haired. The Rig Veda makes frequent

reference to the fact that the conquering Aryans triumphed over

these black and noseless (!) enemies (S. Pigott, Prehistoric

India, Pelican, l950, p.261, and Lord Arundell of Wardour,

Tradition: Mythology, and the Law of Nations, 1872, p.84).

But there was some real connection if not racial identity, between

the Sumerians and these Indus Valley people. It may well be therefore

that the phrase does really refer to skin colour.

Now in the famous six sided prism

of Sennacherib, the king refers to the conquered Canaanites as

"blackness of head people."

GIM-RI SAL-MAT KAKKAD-DIJ-U

GIM-RI SAL-MAT KAKKAD-DIJ-U

In this case

it seems that Canaan could have been a black child, the homozygous

offspring of his mulatto parents, Ham and his wife. The black

people have a quite remarkable series of high cultures to their

credit, and are almost born metallurgists. So were these ancient

Canaanites.

pg.11

of 11 pg.11

of 11  Copyright © 1988 Evelyn White. All rights

reserved

Previous

Chapter *

End of Part III * Next Chapter (Part IV)

Copyright © 1988 Evelyn White. All rights

reserved

Previous

Chapter *

End of Part III * Next Chapter (Part IV)

|