|

Abstract

Table of Contents

Part I

Part II

Part III

Part IV

Part V

|

Part IV: The Technology of Hamitic

People

Chapter 3

Achievements of Ancient High Civilizations

There is little

doubt that the basic cultures in Sumeria (and later on, in Babylonia

and Assyria), in Egypt, and in the Indus Valley, were all non-Indo-European.

The root elements of Mesopotamian civilization in later times

when the Babylonians and Assyrians (both Semitic in origin) had

achieved ascendancy, were still essentially Sumerian. It is pretty

well agreed that these Sumerians were not Semites, being clean

shaven and comparatively hairless like the Egyptians. And from

their language it is quite clear that they were not Indo-European.

Their civilization developed very rapidly and achieved a remarkable

level of technical competence. In the earliest stages of their

history, they seem to have shared many features with the Indus

Valley peop]e who were later overwhelmed by the Aryans, (78) and also with the first

settlers in Northern Syria, and even with the earliest Egyptians.

As further development took place in each of these areas, cultural

similarities became obscured. All these cultures seem to spring

into being already remarkably well organized, with skills in

weaving and pottery making, in the erection of defensive structures

and temple buildings, and with some use of metals from the very

first. It is assumed that the Sumerians were organized into city-states

before the Egyptians were, although it was once held that the

oldest centre of civilization was along the Valley of the Nile.

Although there is, as yet, no evidence of the Sumerians without

basic elements of civilization, it is believed that they came

from the North and East, and it is expected that the origins

of these people (and of the Egyptians and Indus Valley people

also) will in due time be discovered in the general direction

of Jarmo, Sialk, etc. What is now fairly clearly established

is that civilization, the arts and trades, and organized city

life, with the division of labour, social stratification, a leisure

class, written records, and so forth, began, in so far as the

Middle East is concerned, with these Sumerians.

The Sumerians knew what percentages

of metals to use to

78 Childe, Vere Gordon, "India and the

West Before Darius," Antiquity, Mar., 1939, p.15.

pg

1 of 29 pg

1 of 29

achieve the best alloys,

casting a bronze with 9 to 10C% of tin exactly as we find best

today; their pottery was often paper-thin, tastefully shaped

and decorated, and with a ring like true china evidently having

been fired in controlled-atmosphere ovens at quite high temperatures.

Their methods of production led very early to a measure of automation

including powered agricutural equipment that was in the strictest

sense "mechanical"; the control of quality production

was early established by systems of inspection; their factories

were highly organized, and price and wage controls were established

by law. They developed loan and banking companies with outlandish

interest rates, yet still legally controlled; their record keeping

and postal systems were evidently efflcient, mail even being

carried in envelopes.

In addition, the upper classes

lived quite sumptuously, well supplied in many cases with home

comforts and "modern conveniences" � including

running water in some instances, tiled baths, proper disposal

of sewage, extensive medical care, etc. Even libraries existed

and well-organized schools. By comparison their descendants did

not sustain their inheritance, but came to live in that filthy

squalor, precarious poverty, and constant threat of disease,

which misled earlier generations of Europeans to suppose mistakenly

that they themselves were the creators of this superior civilzation.

The greatness of Egypt was more

monumental: Sumerians did not build with stone, for they did

not have it in sufficient quantity, but they left another kind

of monument � imperishable written records. Once these began

to be deciphered, something of their achievements became apparent.

It is by such means that we know, for example, of their mathematics.

Dr. T. J. Meek has told us: (79)

Like the Egyptians the early

Sumerians used the additive method to multiply and divide, but

before 2000 B.C., they had evolved multiplication tables and

tables of reciprocals and of squares and cubes, and other powers,

and of square and cube roots and the like. They had attained

a complete mastery of fractional quantities and had developed

a very exact terminology in mathematics. The correct value of

Pi, and the correct gcometrical formula for calculating the area

of rectangles were known before 3000 B.C., and in the years that

followcd came the knowledge of how to find the area of triangles

and circles and irregular quadrangles, polygons, and truncated

pyramids;

79. Meek, T. J., "Magic Spades in Mesopotamia,"

University of Toronto Quarterly, vol.7, 1938, pp.243,

244.

pg.2

of 29 pg.2

of 29

also cones and the like. By 2000 B.C.,

the theorem attributed to Pythagoras was familiar and they could

solve problems involving equations with two, three, and four

unknowns.

According to

one of the best authorities in this area, they even had developed

an equivalent to our logarithm tables. (80) George Sarton, (81) writing some 20 years later than Meek, could add

to this accomplishment, their knowledge that the angle in a semicircle

is a right-angle, that they could measure the volume of a rectangular

paralleliped, of a circular cylinder, of the frustrum of a cone,

and of a square pyramid. He has summed up this achievement thus:

The Sumerians and their Babylonian

successors left three legacies, the importance of which cannot

be exaggerated:

(1) The position concept in numeration.

This was imperfect because of the absence of zero; (2) the extension

of the numerical scale to submultiples of the unit as well as

to the multiples. This was lost and was not revived until A.D.

1585, with reference to decimal numbers; and, (3) the use of

the same base for numbers and metrology. This too was lost, and

not revived till the foundations of the metric system in 1795.

Later, he wrote

of what we borrowed indirectly from this source:

Many other traces can be detected

in other cultures, even that of our own today � sexagesimal

fractions, sexagesimal divisions of the hours, degrees, and minutes,

division of the whole day into equal hours, metrical system,

position concept in writing of numbers, astronomic tables. We

owe to them the beginnings of algebra, of cartography, and of

chemistry.

Perhaps the

greatest surprise of all is to find that the Greeks did not do

so very well in transmitting this heritage usefully. Thus Sarton

concluded:

The Greeks inherited the sexagesimal

system from the Sumerians but mixed it up with the decimal system,

using the former only for submultiples of the unit, and the latter

for multiples, and thus they spoiled both systems and started

a disgraceful confusion of which we are still the victims. They

abandoned the principle of position, which had to be reintroduced

from India a thousand years later. In short, their understanding

of Babylonian arithmetic must have been very poor, since they

managed to keep the worst features of it, and to overlook the

best. . . .

80. Neugebauer, O. and A. Sachs, Mathematical

Cuneiform Texts, American Oriental Society, Yale University

Press, 1946, p.35.

81. Sarton, George, A History of Scierce, Harvard, 1952,

pp.73, 74, 99, 118.

pg.3

of 29 pg.3

of 29

The Greeks

used their intelligence in a different way and did not see simple

[i.e., practical] things that were as clear as day to their distant

Sumerian and Balylonian predecessors.

It might be

thought that if the Sumerians were really practical people they

would have adopted a decimal systern from the first, and quickly

abandoned the sexagesimal system.But there is much to be said

for the use of 12 instead of 10 as a base number. Ten has only

two factors, 2 and 5. But 12 has 9, 3, 4 and 6, or twice as many:

and in the higher multiples such as 60, the number of factors

is, of course, greater than the corresponding 20 of the decimal

system. Learning to think in terms of such a system would be

difficult for us now that we are so accustomed to the decimal

system, but there are some highly competent mathematicians who

hold that the change could be made and would be advantageous.

This is a matter of opinion, of course, but since we have 10

fingers the choice of 10 as a base seems more natural. And one

must suppose therefore that these practical people saw a real

advantage in using 12 instead. Yet it was purely a practical

matter, and not a theoretical one.

The Greeks were more interested

in theory than practice. The contrast between the Sumerian and

the Greek attitude is seen in their treatment of problems of

Astronomy. In this connection, O. Neugebauer has said:

(82)

A careful analysis of the assumptions,

which must be made in order to compute our texts, shows nowhere

the need for specific mechanical concepts such as are faniliar

to us from the Greek theory of eccentrics or epicycles, or from

the corresponding planetary models of Tycho Brahe or Kepler .

. . . At no point can we detect the introduction of an

hypothesis of a general character.

Samuel Kramer

makes frequent reference to the fact that the Sumerians were

an entirely practical people, with no urge to search for truth

for its own sake, among whom there was not the slightest tendency

either to theorize or generalize, who sought for no underlying

principles, and undertook no experiments for verification. (83)

Sarton gives some illustrations

to show how their mathematics arose out of a practical need,

i.e., business records and

82. Ncugebauer, O., "Ancient Marhematics

and Astronomy" in History of Technology, vol.1, edited

by C. Singer et al., Oxford, 1951, p.799.

83. Kramer, Samuel N., From the Tablets of Sumer, Falcon's

Wing Press, Indian Hills, 1956, pp. xviii, 6, 39, 58 and 59.

pg.4

of 29 pg.4

of 29

transactions. In the

same way geometry reached the Greeks, after being developed to

satisfy entirely practical needs by the Egyptians. This is why

Thales termed it Geometry, for it was required originally to

measure the land in order to re-establish property boundaries

obscured each year by the flooding Nile. (84)

Among the Sumerians and Babylonians,

banking houses sprang up and became the forerunners of world

economics as represented by our international banking institutions.

Two such banks were known from cuneiform records by the names

of Engibi and Sons, established about 1000 B.C., and lasting

some 500 years, and Murasha Sons, founded about 1464 B.C., and

dissolved finally in 405 B.C. The latter established a system

of mortgaging. (85)

Glass was known to the Sumerians

by 2700 B.C., and both they and the Egyptians were experts in

the working of it. (86)

For drilling such substances they used diamond drills, or some

soft material coated with emery or corundum. (87)

A tablet found a few years ago

is inscribed by a certain Dr. Lugal-Edina, dated about 2300 B.C.,

and in it we are told how surgeons of the day had already learned

to set broken bones, make minor and major incisions, and even

attempt operations on the eyes. Sicknesses are given names, and

symptoms carefully noted. Waldo H. Dubberstein of the Oriental

Institute of the University of Chicago, in reporting on this,

has written: (88)

One hundred years of exploration

and research in the field of ancient Near Eastern history have

yielded such astounding results that today it is unwise to speculate

on the further capacities and resources of these early people

along any line of human endeavor.

Medicine was

a carefully regulated profession with legally established fees

for various operations and very stiff penalties for failure or

carelessness, evidently intended to protect the customer

84. Jourdain, Philip E. B., "The Nature

of Mathematics," in The World of Mathematics, vol.1,

edited by James R. Newman, Simon and Schuster, New York, 1965,

pp.1013.

85. Reavely, S. D., "The Story of Accounting," Office

Management, Apr., 1938, pp.8f.

86. Wiseman, P. J., New Discoveries in Babylonia about Genesis,

Marshall, Morgan and Scott, London, 2nd edition, revised, no

date, p.30.

87. Boscawen, St. Chad, in discussing a paper by Sir William

Dawson, "On Useful and Ornamental Stones of Ancient Egypt,"

in the Transactions of the Victoria Institute, vol.26,

London, 1892, p.284.

88. Dubberstein, Waldo H., "Babylonians Merit Honour as

Original Fathers of Science," Science News Letter,

Sept. 4, 1937, pp.148, 149.

pg.5

of 29 pg.5

of 29

and prevent charlatanisrn.

This certainly suggests that the profession was not simply a

"School of Magicians."

Although their buildings have largely

disappeared, they were noteworthy examples of the use of local

materials, rnud-dried brick and reeds. The former are easily

visualized as promising materials; the latter are not. But as

a matter of fact, "reed huts" (mentioned in sorne of

the very earliest tablets) are capable of a surprising beauty

and spaciousness. There is every reason to believe that the design

has not greatly changed through the centuries that intervened.

Floor plans as revealed by excavation seem to indicate similar

structures. See Fig. 7.

By the time the Sumerians arrived

in Mesopotamia, they had domesticated as many animals as were

ever domesticated in that area, with the exception of the horse

which was tamed by the Hittites � although they did have

a draft animal, a mountain ass. And the same may be said of grains.

N. I. Vavilov always considered that the Highland Zone to the

north and east whence they had come, was for this reason the

most likely home with few exceptions, of all such domesticated

plants and animal species as are cornmonly in use today. He called

it the "Source of Species."

(89)

Written records appear at the very

earliest levels, and even at Sialk there seems to have been no

period when they were without the use of metals.(90) The same story is foumd

to be true of Egypt. Here again there is no true "beginning."

The Egyptians, like the Sumerians and the founders of Tell Halaf

in Northern Syria, appear to have been culturally creative from

the very beginning, and to have developed their technology exceedingly

rapidly. Pastoral societies are slower to develop, and the Semites,

who were largely pastoral, contributed little and borrowed much.

Indo-Europeans, meanwlile, did not even have a word of their

own for "city"; the organization of urban community

life with all that this entails in terrns of civilization did

not originate with them. It has been shown that all of their

words for city, town, etc., are loan-words. (91)

Samuel N. Kramer has recently published

a volurne resulting from a lifetime of cuneiform studies which

he titles, From the

89. Vavilov, N. I., "Asia the Source

of Species," Asia, Feb. 1937, p.113.

90. Childe, V. G., What Happcned in History, Penguin,

Harmondsworth, 1942, p.64.

91. Eisler, Robert, "Loan Words in Semitic Languages Meaning

'Town'," Artiquity, Dec., 1939, pp.449ff.

pg.6

of 29 pg.6

of 29

Tablets of Sumer, and his subtitle takes the following form: "Twenty-five

Firsts of Man's Recorded History." (92) It is an impressive collection of "firsts."

One will feel at times that he has introduced a few cases which

are only rightly termed so, by a kind of special pleading. However,

on the whole his collection shows that their inventiveness was

by no means limited to mechanical things, but applies equally

well to forms of literature and indeed to the very idea of collecting

libraries, writing histories, and cataloguing books for reference.

The speed with which Egyptian civilization

developed was equally astonishing. P. J. Wisernan, who has spent

a lifetime in the area studying its past history closely in touch

with the work of archaeologists, has said in this regard: (93)

No more surprising fact has

been discovered by recent excavation than the suddenness with

which civilization appeared. . . . Instead of the infinitely

slow development anticipated, it has become obvious that art,

and we may say "science", suddenly burst upon the world.

For instance, H. G. Wells acknowledges

that the oldest stone building known is the Sakkara Pyramid.

Yet as Dr. Breasted points out, "From the Pyramid at Sakkara

to the construction of the Great Pyramid less than a century

and a half elapsed."

Writing of the latter, Sir Flinders

Petrie stated that, "The accuracy of construction is evidence

of highpurpose and great capability and training. In the earliest

pyramid, the precision of the whole mass is such that the error

would be exceeded by that of a metal measure on a mild or a cold

day; the error of levelling is less than can be seen with the

naked eye."

The same famous

Egyptologist stated that the stone work of the Great Pyramid

is equal to optician's work of the present day. (94) The joints of the masonry

are so fine as to be scarcely visible where they are not weathered,

and it is difficult to insert even a knife edge between them.

Vere Gordon Childe, speaking of

their earliest earthenware, has remarked: (95)

The pottery vessels, especially

those designed for funerary use exhibit a perfection of technique

never excelled in the Nile

92. Kramer, Samuel N., From the Tablets

of Sumer, Falcon's Wing Press, Indians Hills, 1956.

93. Wiseman, J. P., New Discoveries in Babylon About Genesis,

Marshall, Morgan and Scott, London, 2nd edition, revised, no

date, pp.28, 31 and 33.

94. Petrie, Sir Flinders, The Wisdom of the Eyptians,

British School of Archaeology, Publication No.63, 1940, p.89.

95. Childe, V. G., New Light on the Most Ancient East,

Kegan Paul, London, 1935, p.67.

pg.7

of 29 pg.7

of 29

pg.8

of 29 pg.8

of 29

Valley. The finer ware is extremely thin,

and is decorated all over by burnishing be£ore firing,

perhaps with a blunt toothed comb, to produce an exquisite rippled

effect that must be seen to be appreciated.

J. Eliot Howard

has stated that the hieroglyphics of the earliest periods indicate

that pottery, metallurgy, rope making, and other arts and techniques

were already well developed, (96) and W. J. Perry � quoting de Morgan � has

written: (97)

What appears at a very early

date in Egypt is perfection of technique. The Egyptian appears

from the time of the earliest Plaraohs as a patient, careful

vorkman, his mind like his hand possessing an incomparable precision

. . . a mastery hat has never been surpassed in any country.

A carved (or

ground?) diorite head from Egypt was sold in London some years

ago for the sum of $50,000, and it was considered by the experts

at the time "never to have been surpassed in the entire

history of sculpture." (98)

It is hard to decide which of these

two civilizations produced the most remarkable metal wares. The

jewelled weapons of their noble dead are simply beautiful. There

are no essential metallurgical techniques which they had not

mastered very early in their history. These include filigree,

mold and hollow casting, intaglio, wire-drawing, beading, granulation

(in water?), welding, inlaying of one metal with another, sheeting

hammered so thin as to be almost translucent, repoussee, gilding

on wood and other materials, possibly spinning of metal -- and

later, even electroplating using a form of galvanic cell catalyzed

with fruit juices and housed in a small earthenware jar. (99) One of these is illustrated

in Fig. 10.

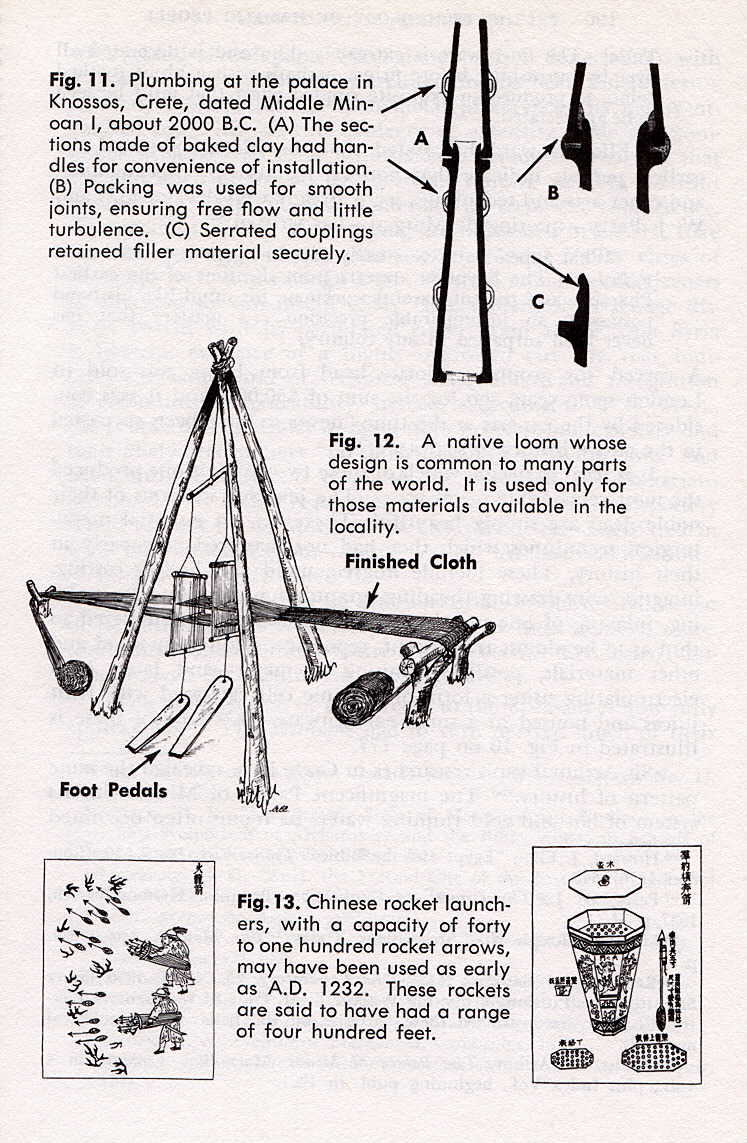

Sir Arthur Evan's researches in

Crete have revealed the same pattern of history. (100) The magnificent Palace

of Minos with its system of hot and cold running water, its rooms

often decorated

96. Howard, J. Eliot, "Egypt and the

Bible," Transactions of the Victoria Institute, vol.10,

London, 1876, p.345.

97. Perry, W. J., The Growth of Civilization, Penguin,

Harmondsworth, 1937, p.54.

98. Macoffin, Ralph N., "Archaeology Today," The

Mentor, Apr., 1924, p.6

99. Reported in "Batteries B.C." The Laboratory,

vol.25, no.4, 1956, Fisher Scientific Co., Pittsburgh, quoting

Willard F. M. Gray of the General Electric Company. Gray reconstructed

these batteries on the basis of archaeological materials.

100. Evans, Sir Arthur, The Palace of Minos, Macmillan,

London, in 4 vols., plus Index vol., beginning publication in

1921.

pg.9

of 29 pg.9

of 29

with a kind of wall-paper

effect done (as it is done today) with a sponge, (101) its extraordinary architecture,

its beautiful pottery � in many cases patterned upon metal

prototypes � its highly organized court life, and its evidence

of extensive trade and commerce overseas � all these achievements

demonstrate clearly that the craftsmen of the ancient Minoan

Empire vere in no whit behind the Egyptian and Sumerian in technical

competence. Two sections of their water piping are illustrated

in Fig.11. Like the drainage and sewage systems of the Indus

Valley cities of Mohenjo Daru and Changu Daru, they are equal

in effectiveness to anything we can install today. The underground

sewage disposal system with its perforated street drain above

from Syria is likewise evidence of a highly organized city life

that indicates the same kind of technical achievement and recognition

of community responsibility. Indeed, according to T. J. Meek,

the people of Tell Halaf in Syria were never without metals,

and their finely fired pottery "no thicker than two playing

cards" and beautifully designed, is equal to the best that

the Sumerians produced. (102) It is closely parallelled by some of the earliest

pottery found at Susa by de Morgan, (103) a city which was closely tied in with the Sumero-Egyptian-Indus

Valley "Archaic Civilization," as W. J. Perry aptly

called it.

Here, in these areas, lie the roots

of all Western Civilization in its earlier stages of development.

From these centres, sometimes directly, sometimes indirectly

(as via the Etruscans), Europe derived the inspiration of its

culture.

The indebtedness of the Greeks

to the Minoans is now ful]y appreciated. (104) The Minoans had in turn derived much of their

101. See Bulletin of the Royal Ontario

Museum of Archaeology, No.11, March, 1932, p.7.

102. Meek, T. J., "The Present State of Mesopotamian Studies,"

in the Haverford Symposium of Archaeology and the Bible, American

Schools of Oriental Research, New Haven, 1938, p.161.

103. Spearing, H. G., "Susa, the Eternal City of the East,"

in Wonders of the Past, vol.3, edited by by Sir J. Hammerton,

Putnam's, 1924, p.582.

104. Bibliography on Aegean pre-history:

Blegen, Carl

W., Zygouries: a Prehistoric Settlement in the Valley of Cleonae,

Harvard, 1928.

Bosanquet, R.

C., Excavations at Phylakopi in Melos, Macmillan, 1904.

Dinsmoor, W.

B., The Architecture of Ancient Greece, Batsford, 1950.

Evans, Sir Arthur,

The Palace of Minos, Macmillan, 4 vols., 1921-1935.

Heurtley, W.

A., Prehistoric Macedonia, Cambridge, 1939.

Holmberg, Erik

J., The Swedish Excavations at Asea in Arcadia, Leipzig,

1944. (continued)

pg.10

of 29 pg.10

of 29

culture from the Egyptians.

Some influences reached Greece directly from Asia Minor. Between

these three sources can be divided almost everything in Greek

culture that has a technical connotation: mathematics, architecture,

metallurgy, medicine, games, and even the inspiration of much

of their art � all was borrowed from such non-Indo-European

sources. Even their script was borrowed. In fact, one might say

their very literacy, for influential figures like Socrates, far

from contributing anything to the art of writing, actually strongly

opposed it as a threat to the powers of memory.

The same is true of Rome. The part

played by the Etruscans in the foundation of Roman Civilization

is immense. Sir Gavin de Beer, in a recent broadcast in England

said: (105)

It may

seem remote to us (to ask who the Etruscans were), and yet it

affects us closely for the following reason. We regard the Romans

as our civilizers, and we look up to them as the inventors of

all sorts of things they taught us. But it is now clear that,

in their turn, the Romans learned many of these things from the

Etruscans.

De Beer holds

that whatever else might be said about these interesting people,

their language at least was non-Indo-European, and they were

not related either to tle Romans or the Greeks. With this agrees

M. Pallottino, an authority on the Etruscans. (106) George Rawlinson, the great Orientalist and classical

scholar, says in this respect: (107)

The Romans

themselves notwithstanding their intense national vanity acknowledged

this debt to some extent and admitted that they derived from

the Etruscans their augury, their religious ritual, their robes

and other insignia of office, their

104. Mylonas, George, Prehistoric

Macedonia, Studies in honour of E. W. Shipley, Washington

University Series, Language and Literature, no.11, 1949, pp.55f.

Pendlebury, J. D. S., The Archneology

of Crete, Methuen, London, 1939.

Seager, Richard B., Explorations

in the Island of Mochlos, American School of Classical Studies,

at Athens, published in Boston, 1912.

Valmin, M. Natan, The

Swedish Messenia Expedition, Oxford, 1938.

Wace, A. J. B., Prehistoric

Thessaly, Cambridge, 1912.

Weinberg, Saul, "Neolithic

Figurines and Aegean lnterrelations," American Journal of

Archaeology., Apr., 1951, pp.121.

Xanthoudidcs, Stephanos,

The Vaulted Tombs of Mesara, Liverpool University Press,

and Hodder and Stoughton, London, 1924.

105. De Beer, Sir Gavin, "Who Were the Etruscans,"

The Listener, CBC, London, Dec. 8,1955, p.989.

106. Pallottino, M., The Etruscans, Penguin, Harmondsworth,

1955.

107. Rawlinson, George, The Origin of Nations, Scribner,

New York, 1878, p.111.

pg.11

of 29 pg.11

of 29

games and shows, their earliest architecture,

their calendar, their weights and measures, their land surveying

systems, and various other elements of their civilization. But

there is reason to believe that their acknowledgment fell short

of their actual obligations and that Etruria was really the source

of their whole early civilization.

To this list,

D. Randall MacIver adds their martial organization � and

even in all probability the very name of the city itself. (108)

Out of Africa has come to us far

more than just the Egyptian contribution, even were this not

a sufficient one. One does not think of Africa as particularly

inventive. As a matter of fact, however, so many new things came

from that great continent during Roman times that they had a

proverb, "Ex Africa semper aliquid," which freely

translated means, "There is always something new coming

out of Africa." (109) Among other things out of Africa came "Animal

Tales" � the Fables � from Ethiopia. Edwin W. Smith

and Andrew M. Dale have pointed out: (110)

It might indeed be claimed that

Africa was the home of animal tales. Was not the greatest "literary

inventor" of all, an African, the famous Lokman, whom the

Greeks not knowing his real name called Aethiops (i.e., Aesop)

?

Even in medicine

Africans have some remarkable achievements to their credit. To

mention but two: the pygmies of the Ituri Forest had invented

an enema quite independently of its South American Indian counterpart,

(111) and it is

known that Caesarean operations were successfully undertaken

in childbirh emergencies before the White Man had succeeded in

doing it. (112)

Out of Ethiopia came also coffee. (113) And quite recently African art has been the "inspiration"

(for good or ill) of new forms of art. Very recently a kind of

rocking stool inspired by an ingenious African prototype came

into popularity.

Their engineering skill is often

revealed in very simple things. A sedan chair is so designed

that the rider receives a

108. MacIvor, D. Randall, "The Etruscans,"

Antiquity, vol.1 , June, 1927, p.171.

109. Editorial in Endeavour, April, 1945, p.41.

110. Smith, Edwin W., and Andrew M. Dale, The Ila Speaking

Peoples of Northern Rhodesia, vol.2, Macmillan, London, 1920,

p. 342.

111. Coon, C. S., A Reader in General Anthropology, Holt,

New York, 1948, p.340.

112. Ackerknecht, Erwin, "Primitive Surgery," American

Anthropologist, New Series, vol.49, Jan.-Mar., 1947, p.32.

113. Anonymous, "The Story of Coffee," The Plibrico

Firebox, Plibrico Firebrick, Toronto, vol.22, July-Aug.,

1948, p.4, 5.

pg.12

of 29 pg.12

of 29

pg.13

of 29 pg.13

of 29

minimunn of jolts and

rockings due to the unevenness of the ground. It is a kind of

super-whiffle-tree sling that equalizes the load and guarantees

smooth passage.

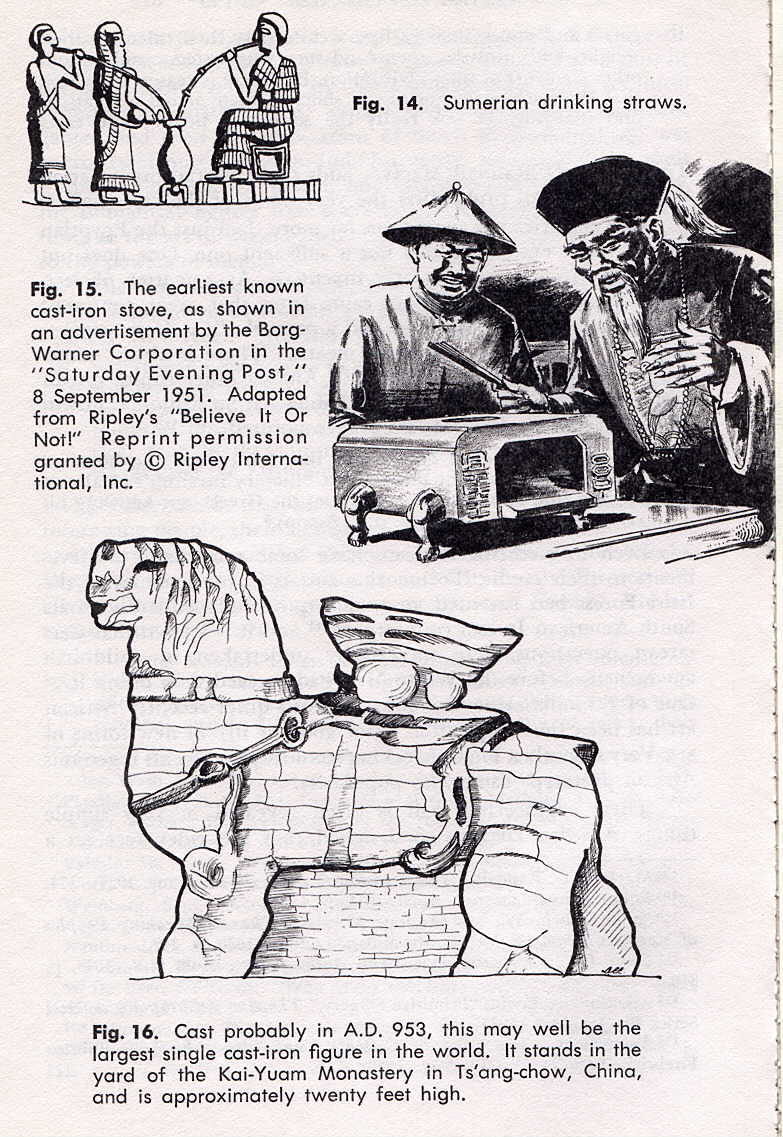

As a further witness to the sarne

kind of genius for simplified construction an African loom is

shown in Fig.12. It makes the most effective use of locally available

raw materials, and in fact uses their actual form to the best

advantage.

Almost every African comrmunity

of any size has its own smelting furnace and smithy. No part

of this iron working art has been borrowed from Europe. The whole

process (and the refinernents found in some cases) is a native

invention. The bellows used to increase the oxygen supply and

thereby the heat at the hearth, are of native design and manufacture,

and are very varied in form. The pipes which convey the air into

the furnace are also homemade. Suitable clay is plastered around

pieces of wood of the proper size and shape (curved, straight,

or even forked) and then the whole is burned in a fairly hot

fire. This reduces the wooden insert to ashes and leaves the

desired pipe form, shaped and baked, ready for use. When the

ore has been reduced and the metal is removed from the dismantled

furnaces, it is worked by hand. The rnetal may be hammered into

sheets, drawn into wire, or forged into other forms, such as

vessels and blades, as desired. It is not surprising that we,

having largely learned from Africa the basic techniques of iron-working,

should refer to our iron metal-workers as Blacksmiths. R. J.

Forbes says that although today African srniths often obtain

their raw nraterials from European sources, the Negro smitlrs

"are very ingenious craftsmen in inventing and using new

tools and types of bellows." (114)

Among the literary achievements

of the Egyptians must be listed what was surely the first "moving-picture"

sequence, (115)

and the first Walt Disney Cartoon. (116) Gloves and camp-stools are found first in Crete,

(117) soap in Egypt,

(118) virtually

all carpenter's

114. Forbes, R. J., Metallur,gy in Antiquity,

Leiden, 1950, p.64. 1

115. "A Cinematograph Touch in Ancient Egyptian Art:

Wall-paintings that Suggest Moving Pictures," reproduced

from P. E. Newberry, Beni Hasan, in The Illustrated

London News, Jan. 12, 1929, Plate 50, 51.

116. Hambly, Wilfrid D., "A Walt Disney In Ancient Egypt,"

in a letter to the editor, Scientific Monthly, Oct., 1954,

pp 267, 268; has illustrations of "animated animal figures"

behaving like people!

117. Gloves and campstools: see Axel Persson, The Religion

of Greece in Prehistoric Times, University of California,

1942, p.77.

118 Soap: see a paper on this by Rendel Harris, Soap,

Sunset Papers, published privately in England, in 1931.

pg.14

of 29 pg.14

of 29

tools (saws, squares,

bucksaws, brace and bit, etc.) from the Etruscans (119) � with a novel brace

and bit (120)

� and the "level" from Egypt. (121) The Etruscans invented lathes. (122) The Egyptians built a pipe-organ using water apparently

to obtain a uniform air pressure. (123) Folding umbrellas and sunshades were first designed

in China (124)

and were not introduced into England till centuries later, where

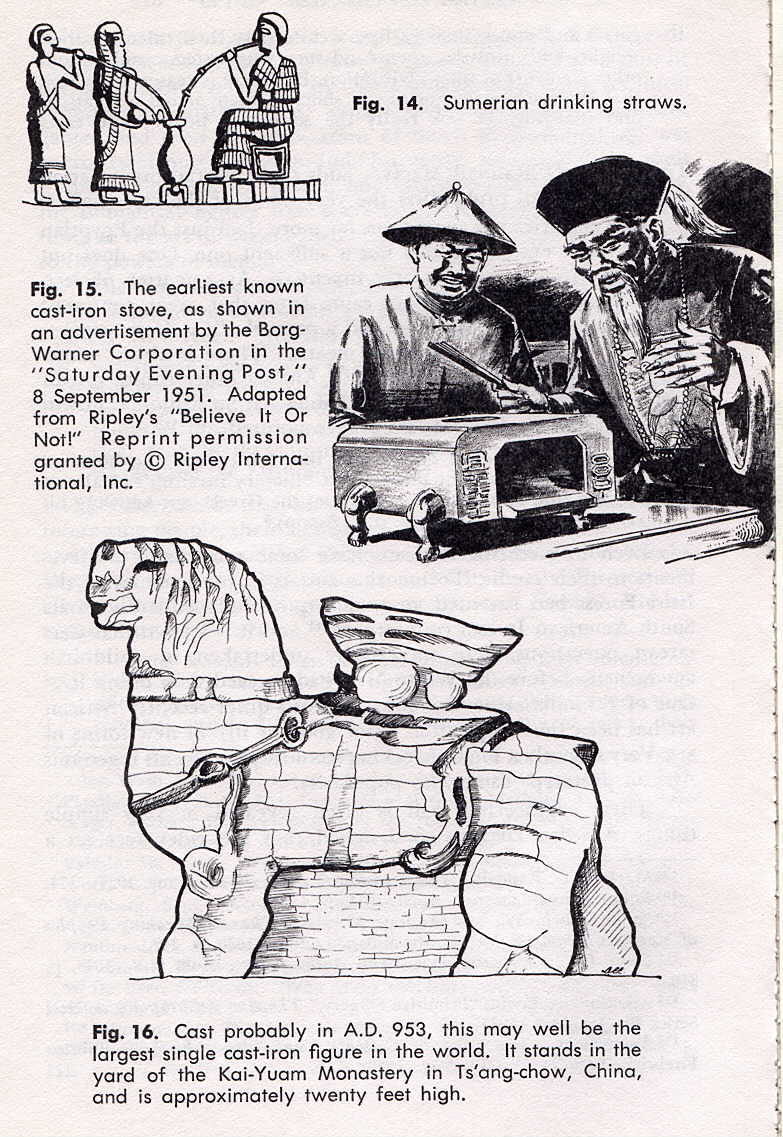

the introducer apparently almost lost his life. The Sumerians

used straws for drinking (125) (see Fig.14) and bequeathed to their successors chariot

wheels which were made of plywood using the same technique for

the manufacture as we use today. (126) Africans were using vaccines long before the White

Man adopted them. (127)

And there is a record of the invention of a malleable glass,

the secret of which was destroyed by the ruling monarch, along

with the originator, for fear of upsetting the economy. (128) Every form of building

technique now commonly used (including concrete) is found among

non-Indo-Europeans, and in many cases long antedating the Romans,

especially the arch, barrel vault, dome, and cantilever principle

of construction. The barrel vault was achieved in Babylonia without

the need of a supporting scaffold under it, by starting against

an upright wall which was later removed. The cantilever principle

was used by the Egyptians, among others, in strengthening their

larger sea-going vessels, to prevent them from "breaking

their backs," as marine engineers term it.

119. Tools: see George M. A. Hanfmann, "Daidalos

in Etruria," American Journal of Archaeology, Apr.-June,

1935, pp.192ff.

120. Brace and bit: an illustration of this is given in The

Illustrated London News, April 12, 1930, p.623, in a series

of articles by G. H. Davis and S. R. K. Glanville entitled, "Life

in Ancient Egypt: Astonishing Skill in Arts and Crafts."

121. Levels: see George Sarton, A History of Science,

Harvard, 1952, p.124, note 94.

122. Lathes: see Charles Singer, et al., A History

of Technology, vol.1, Oxford, 1954, pp.192, 518.

123. Apel, Willi, "Early History of the Organ," Speculum,

vol.23, 1948, p.191-216.

124. A number of bronze castings used in the construction of

these large umbrellas are to be seen in the Royal Ontario Museum,

Toronto.

125. Well known from the monuments and from seals. The line drawing

in the illustration is probably from a seal (Fig.14).

126. Linton, Ralph, The Tree of Culture, Knopf,

New York, 1956, p.114.

127. Vaccines: see Melville Herskovits, Man and His Works,

Knopf, New York, 1950, p.246.

128. Malleable glass: the details of this are given by Stanko

Miholic, "Art Chemistry," Scientific Monthly,

Dec., 1946, p.460.

pg.15

of 29 pg.15

of 29

James

Hornell, an authority on watercraft as developed by primitive

and ancient people, opened a paper on the subject with these

words: (129)

There

can be no doubt that to Asiatic ingenuity we owe the beginnings

of the world's principle types of Water Transport. Early man

in Asia invented means of extraordinary diversity to enable him

to cross rivers, etc.

The vessels

illustrated or referred to include every type of small craft

from mere floats to coracles and large outrigger sailing vessels,

etc. If we bear in mind that China gave us the stern-post rudder,

the watertight compartment construction, as well as canal locks

for inland waterways, (130) and that the Koreans built the first true battleship,

with iron cladding -- notwithstanding the claims made for "Old

Ironsides" in Boston Harbour -- it will be seen that we

have not contributed a great deal basically to marine engineering.

Isabella L. Bishops has said of this Korean warship, that it

was named Tortoise Boat, and was "invented by Yi Soon Sin

in the 16th century, enabling the Koreans to conquer the great

Japanese General Hideyoshi in Chinhai Bay." (13l)

Naphtha gas was first used by the

Sumerians, (132)

eyesalves in multiple tubes probably by the same people, (133) but spray-painting by

paleolithic man! (134)

Cigarettes were known to the North American Indians long before

Europeans had ever heard of tobacco; (135)

129. Hornell, James, "Primitive Types

of Water Transport in Asia: Distribution and Origins," in

Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, London, 1946, Parts 3 and

4, pp.124-141.

130. Needham, J., Science and Civilization in China, 1954,

vol.1, pp.240-243.

131. Article "Koreans" in the Encyclopedia Britannica,

14th Edition, 1937, vol.13, p.489, with illustraton.

132. Naphtha: as we have already mentioned, the Chinese piped

this gas as early as 450 B.C. But it was also used by the Babylonians

for divination purposes according to R. J. Forbes in A History

of Technology (edited by Charles Singer, et al, Oxford,

1954, vol.1, p.251). By the same author, it is said to have been

used by the Sumerians, probably, in furnaces for heating metals,

Metallurgy in Antiquity, Brill, Leiden, 1950 p.111.

133. Forbes, R. J., in A History of Technology,

(edited by Charles Singer, et al, Oxford, 1954),

vol.1, p.293.

134. Leakey, L. S. B., in A History of Technology, (see

above), vol.1, p.149. This is possibly begging the point a little!

It is assumed from the nature of certain paintings that they

were done by blowing (or splattering) the paint from the mouth

(!) using baffles to limit it as required. Certainly it does

seem to have been sprayed, somehow.

135. Cigarettes: see an editorial note, in "The Sacred Cigarette,"

Discovery, June. 1958, p.262. Found by the thousands.

. . . We have already mentioned cigar-holders: and, of course,

the Indians were originators of the pipe for tobacco smoking.

pg.16

of 29 pg.16

of 29

spectacles are probably

a Chinese invention; (136) and safety pins came from the Etruscans. (137) The Chinese did many

things with glass, for, according to Bruno Schweig, (138) there is evidence of

glass mirrors as early as 2000 B.C., and although the source

of my information here is not the best, there is a reference

to the first "windows" of glass in a collection of

Chinese Stories. It is said that in the reign of Emperor Ming,

a man named Wing Dow invented a "device" which he called

Looking-through-the-Walls, whence it is claimed we now derive

our word Window, a corruption of the inventor's name. (139)

Although the abacus seems a very

slow and primitive way of making calculations, recent experiments

undertaken by experts in both the ancient instrument and the

modern electrically operated comptometer, have shown that in

the hands of a skilled operator it can hold its own against all

mechanical devices (excluding computers) except in one particular

type of calculation. (140)

LeComte du Nouy, after a backward

look at the "rostrum of ingenuity" which meets the

eye from antiquity, expresses the conviction: (141)

Intellience does not seem to

have increased radically in depth during the last 10,000 years.

As much intelligence was needed to invent the bow and arrow,

when starting from nothing, as to invent the machine gun, with

the help of all anterior inventions.

One demonstration

of the wisdom of this observation is that the experts find it

quite impossible to determine now how the first bow ever came

to be invented. Their reconstructions are as varied as can be:

which tends to show that such a weapon would certainly not occur

easily to its originator, since we cannot even imagine how it

originated with one right in front of us.

136. Spectacles: see Ethel J. Alpenfels, anthropologist

with the Bureau for Intercultural Education, in an article entitled,

"Our Racial Superiority," abstracted in The Reader's

Digest, Sept., 1946, p.81, from Catholic World, July,

1946, p.328ff.

137. Safety pins: illustrated in an article by D. Randall MacIvor,

"The Etruscans," Antiquity, vol.1, Jurne, 1927,

p.170.

138 . Schweig, Bruno, "Mirrors," Antiquity,

Sept., 1941, p 259.

139. Windows: see Phyllis R. Feuner, Giants, Witches, and

a Dragon or Two, Knopf, New York, 1913, p.185.

140. Abacus: these experiments were reported as a note under

"Misplaced Conceit," in His (Inter-Varsity Christian

Fellowship, Chicago), Oct., 1957.

141. Du Nouy, Le Comte, Human Destiny, Longnans Green,

New York, 1917, p.139.

pg.17

of 29 pg.17

of 29

Finally, we come to the great contribution made by

China. (142) If

we should ask today whlat three things above all have contributed

to or are contributing to our present conquest of the earth,

we might possibly agree that printed matter, a convenient medium

of exchange of some kind (i.e., currency), and powered propulsion

are fundamental. All of these � and of course hundreds besides

� we have derived from China, though often indirectly, via

the Arab world.

For our wheeled vehicles we initially

used draft animals domesticated in the Middle East, but because

of the inefficiency of harnessing methods, these draft anirnals

could not pull nearly as much as they do now, due to the lack

of an effective harness which was meanwhile being developed in

China. But we have, of course, long since passed out of the draft

horse age into the jet-propulsion era. The motive power for such

high-speed engines was likely inspired by the Chinese. In the

air, China and the Far East anticipated us in virtually every

form of airborne vehicle or device, including rockets, but also

kites, gliders, balloons, parachutes, weather forecasting, and

even the helicopter in the form of a toy.

The fact that we have obtained

from China silk, porcelain, explosives, paper, printing with

movable type, paper money, the magnetic compass, and mechanical

water clocks, is so well known that it needs little or no elaboration.

That the Chinese anticipated us in the use of gas for cooking

and heating, cast iron, flame weapons in warfare, and, as has

been stated above, the initial conquest of the air, is possibly

less well known. But in addition to this, they initiated the

use of fingerprinting for identification purposes, chain pumps,

thc crossbow and a repeating bow with 19 shots per load, gimbal

suspension systems, the draw loom, the rotary fan and a winnowing

machine, piston bellows, wheel-barrows, stirrups, a greatly improved

harness for draft animals that enabled them to pull almost twice

as heavy a load, deep drilling methods, and much more.

Marco Polo gives us quite an extensive

account of the use of paper money. (143) He says it was issued in various denominations, stamped

authoritatively by the Governor of the Mint, and circulated as

the only form of valid currency over a very wide

142. Under "Science and Civilization

in China," in the section "The Progress of Science,"

Discovery, Nov., 1957, p.458.

143. Polo, Marco, The Travels of Marco Polo, Library Publications,

New York, no date, Chap.24, pp.137-140.

pg.18

of 29 pg.18

of 29

geographical area. The

bills, he says, were quite remarkably strong and did not tear

easily; any which had been torn, however, or had suffered defacement,

were recalled to the Mint and replaced. Strikingly reflecting

our own bills of a few years ago, they contained a promise that

they would be redeemed for certain fixed quantities of either

precious stones or metals upon request. Foreign merchants could

not sell their jewels or precious metals on the open market,

but were required to turn them in at the Mint, where they received

recompense in paper money.

Consider how great such an innovation

really was. Marco Polo says, a man who wished to move could turn

in hundreds of pounds (by weight) of valuable goods in personal

property, walk away with a pocketful of money so light as to

be hardly noticeable, with which in some other part of the Empire

he could recover his hundreds of pounds of goods. Everywhere

else in the world men were loaded down with the weight of their

possessions, which often took such a form as to be almost worthless

once the owner left his own locality. What such a scheme did

for trade and commerce is incalculable. What paper money does

for us today is virtually to keep our civilization running. Maybe

we would have come to it anyway in time, but certainly we did

not originate the idea. It originated in the 13th century with

the Great Khan.

Needham has pointed out,

it was often many centuries before such inventions reached the

West from China. And he also notes that China received from the

West very little in return: actually, only four items -- the

screw principle, a force pump for liquids, the crankshaft, and

clockwork powered by a spring. (144) Of these, only the screw principle and an alternative

form of it (the windmill) seem actually to be to the credit of

Indo-Europeans, possibly the Greeks for the screw and the Persians

for the windmill. There is evidence that even the screw was obtained

from Egypt.

Needham has pointed out that the

art of drilling deep wells or boreholes as used today in exploiting

oil reserves is specifically of Chinese origin. (145) He mentions that the

use of graticules on maps to simplify the specifying and location

of places, is probably of Chinese origin, although Ptolemy also

employed this

144 Needham, J., Science and Civiliation in

China, Oxford,1954, vol.1, p.241. But there is some question

about the Screw Principle. Archimedes may have "borrowed"

it from Egypt.

145. Ibid., p.244.

pg.19

of 29 pg.19

of 29

method. (146) For almost all Needham's

illustrations, one thing can be said, to use his own words: (147)

Firm evidence for their use

in China antedates, and sometimes long antedates, the best evidence

for their appearance in any other part of the world. . . .

Then he has

quoted Toynbee as having said --

How ever far it may or may not

be possible to trace back our Western mechanical trend toward

the origins of our Western history, there is no doubt that a

mechanical penchant is as characteristic of the Western civilization

as an esthetic penchant was of the Hellenic.

Of this observation,

Needham has said, "It is to be feared that all such valuations

. . . are built on insecure foundations." The fact is, we

simply do not have any such penchant if we judge our "racial"

character by looking at our achievements prior to the time we

began to borrow from non-Indo-Europeans. Since that time, racial

mixture has taken place on such a scale, and with it, of course,

"cultural" mixture also, that it is difficult to say

for certain who is and who is not Indo-European in many cases.

About all we can do is attempt to gain a certain measure of objectivity

in this regard by looking more carefully at the actual achievement

involved in many borrowed elements of our civilization which

we now think simple and obvious.

Take as an example the preparation

of silk. Sarton wrote: (148)

Consider what the invention

implied � the domestication of an insect, the "education"

of silkworms, the cultivation of the white mulberry, the whole

of sericulture!

It involved

the recognition of the possibilities of the material in the first

place. Spider web is one of the strongest known natural filaments,

but it does not seem that anyone ever thought of cultivating

spider web for this purpose. The idea of such a possibility is

not enough. It requires considerable energy to turn it into a

working industry, and although it seems highly improbable that

it was done in a single step, somebody must have been alive to

the practical advantages of making the effort and have demonstrated

it could be done. But, having developed the "industry"

until it was producing results, there it was left, with virtually

no effort to extend it or improve the technique or seek for substitute

insects or even attempt to make a synthetic material using the

same kind of substance produced by other means.

146. Ibid., p.245.

147. Ibid., p.241.

148. Sarton, George, A History of Science, Harvard, 1952,

p.5, note 4.

pg.20

of 29 pg.20

of 29

This is the kind of

thing that Indo-Europeans are good at; but the initial stimulation

always seems to have come from somewhere else.

Needham has drawn attention to

the fact that the Chinese have excelled in the arts of war, inventing

many new weapons and new methods of attack or defense. The repeating,

or "magazine" cross-bow, of which an example is to

be found in the Royal Ontario Museum, is surely the world's first

machine gun. (149) Credit

(?) must also be given to them for the invention of flame weapons

and smoke bombs. .Athough the former appeared in the Mediterranean

area first in North Africa, being used against the Rornans, there

is no doubt that the Arabs derived them from the Chinese, for

they called them "Darts of China." In a paper on chemical

warfare published some years ago in the United States, Harold

Lamb had this to say: (150)

.A search

through Oriental annals reveals other ancestors of present European

weapons. But it is a little surprising to find thle modern hand-grenade,

flame-thrower, and cannon in use in Asia centuries ago.

In Roman days vases filled witll

a fire compound were employed by the Persians at the Siege of

Petra. 'I'his compound was sulfur, asphalt, and naphtha, and

the vases were cast by mangonels (a kind of giant catapult).

The flames which sprang up when the vessel broke could not be

extinguished. This was the origin of the much talked about Greek

fire, which they, having borrowed it from the Arabs . . . were

surprised to find would continue to burn on water, a fact which

mystified the early Crusaders.

Haram al-Raschid used sulfur-naphtha

compound at the siege of Heraclea. . . . At the siege of

Acre, a Damascus engineer destroyed the wooden towers of the

Crusaders by casting against them light clay vessels of the fluid

until everything was well saturated. Then a flaming ball was

thrown out and, as we reaf in one old Chronicle, "all was

destroyed by flame, man, weapons, and all."

During the 13th century, flame

weapons were highly developed by the Arabs. They had hand-grenades

-- small glass or clay jars that ignited when they broke; and

a curious fire-mace, that was to be broken over the head of a

foe, its owner keeping well to windward!

Flame throwers appeared in the

form of portable tubes that could burn a man to ash at 30 feet.

[We still cannot do much better - -or worse - -with modern weapons!]

Some of the

149. Repeating bow: this is described in "Crossbow,"

Bulletin of the Royal Ontario Museum of Archaeology, no.10,

May, 1931, p.11.

150, Lamb, Harold, "Flame Weapons," ChemicaI Warfare

Magazine, Dec., 1927, p.237.

pg.21

of 29 pg.21

of 29

names of these flame weapons, such as

the Chinese Flower, and so on, indicate that they had their origin

in that country. In fact we find the Chinese of the 13th century

very familiar with destructive fire. They had the pao that belched

flaming power, and and fie-ho-tsing, the "spear of fire

that flies."

It seems, then,

that the Arabs borrowed much from the Far East � paint brushes

(but with the original pig bristles replaced by camel hair �

for religious reasons), paper manufacture, block printing, silk,

alchemy, and such weapons of war as the above in addition to

explosives. They were great carriers but apparently somewhat

uninventive except possibly during one short period of their

history.

Another document prepared by the

Office of the Chief of the Chemical Warfare Service (Washington,

1939) opens with these words: (15l)

Ghengis Khan, famous ruler of

the Mongols and of China, used chemicals in the form of huge

balls of pitch and sulfur shot over the walls of besieged towns

to produce combinations of screening smoke, choking sulfur fumes,

and incendiary effects as a standard routine of attack.

Even "irritating"

gases were used by the Arabs against the Roman Legions in North

Africa as early as A.D. 220. According to Capt. A. Maude, the

secret of this weapon was finally learned by the Romans by Julius

Caesar, through the capture of a Prince of Mauritania named Juba

II, sulsequently married to Selene, the daughter of Cleopatra.

(152)

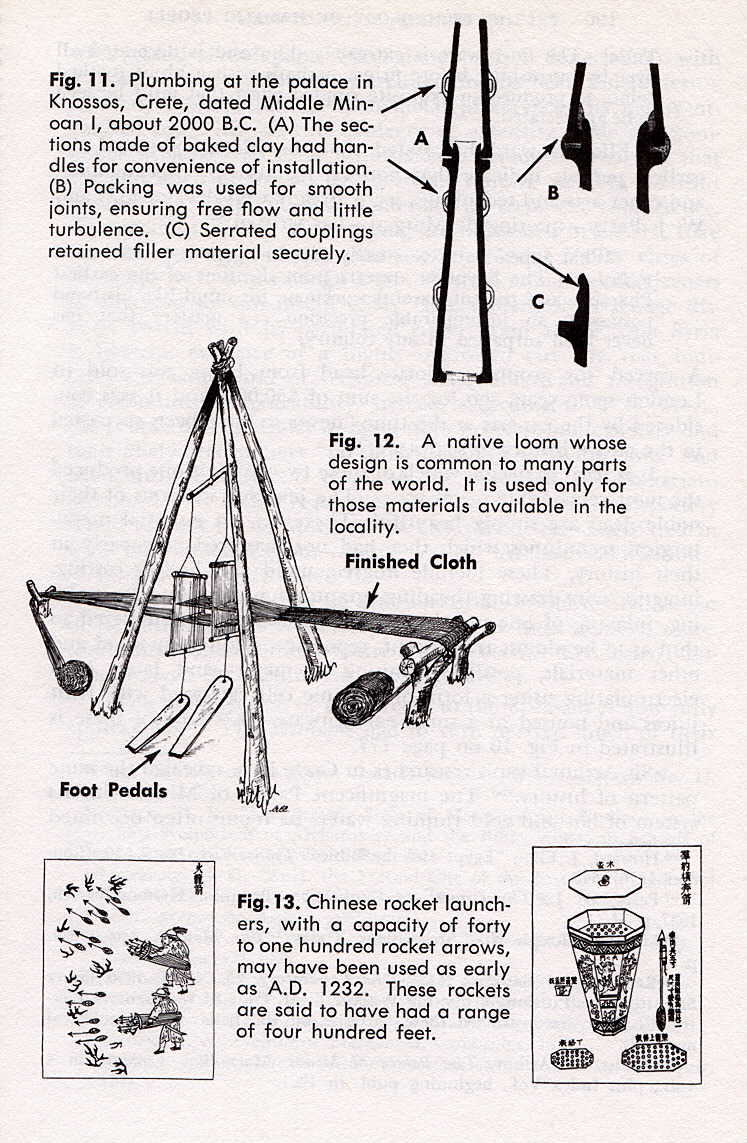

The Chinese, curiously enough,

did not make much use of their explosives in warfare by developing

cannon until the idea was suggested to them by Europeans. But

they did make rocket arrows, and their launching devices were

certainly the predecessors of modern multiple rocket launchers.

An illustration of these, from a Chinese manuscript, is given

in Fig.13. Psychological weapons were developed � large arrows

with whistling or screaming heads on them, guaranteed to stampede

horses. Some of their bows were so beautifully designed that,

as Klopsteg has shown, they could shoot up to half a mile with

them. (153)

Their gunpowder burned rather slowy

and unevenly. Hence it was not too effective in cannon. But this

did not deter them.

151. "The Story of Chermical Warfare,"

Chemical W'arfare Magazine, Jan., 1939, p.1.

152. Maude, A., "Ancient Chemical Warfare," Journal

of the Royal Army Medical. Corps, vol.62, 1934, p.141.

153. Klopsteg, Paul E., Turkish Archery and the Composite

Bow, privately published in Toronto, 1947.

pg.22

of 29 pg.22

of 29

They made use of this.

They arranged the cannon's barrel so that it was free to move

and then fastened the charge in it so that it stayed with the

weapon. Thus they had a jet propelled rocket. They made the tube

out of tightly wound paper to save weight and put a point on

it for better flight. But they soon found that because of the

uneven burning of the propellant, the rocket's flight was somewhat

erratic. They overcame this by putting a trailing stick on it

to steady it. At first this stick had feathers, but they found

that the feathers were simply burned off. But these feathers

proved unnecessary. However, regardless of the size of the rocket,

they found that it had the best balanced flight when the stock

was seven times as long as the rocket head. This is still found

to be so. (154)

Willey Ley has written that the

Arabs learned of these weapons from Chinese, and thus called

them "Alsichem alkhatai," or Chinese Arrows. (155) The French Sinologist,

Stanislas Julien, has found references to these rockets in China

as early as A.D. 1232.

In metallurgy (and in alchemy)

the Chinese were far ahead of the West. R. J. Forbes, a foremost

authority on metallurgy in antiquity, has told us that they were

making cast iron stoves by at least 150 B.C. (156) A picture of one such stove is given for interest's

sake, though the original source of the illustration is not known

(see Fig. 15). It was used by the Borg-Warner Corporation in

an advertisement.

Another metallurgical journal gives

a picture of a huge, single-piece, cast iron statue, which is

believed to have been set up in A.D. 953. This is held to be

one of the largest single iron castings ever made. It is shown

in Fig.16.

As a matter of interest, it is

sometimes pointed out that the Hittites (possibly a non-Indo-European

people with an Indo-European aristocracy), who vanished from

history so completely that their very existence was once doubted,

are referred to in cuneiform documents as the Khittai, and sometimes

as the Khattai. C. R. Conder suggested that they disappeared

because when their Kingdom came to an end, the people packed

up and travelled East where they left their name associated with

China and the Far East, in the form ''Cathay.'' (157) The Arab call the

154. Coggins, Jack, and Fletcher Pratt, Rockets,

Jets, Guided Missiles and Space Ships, Random House, New

York, 1951, p.4, with foreword by Willey Ley.

155. Ley, Willey, "Rockets," Scientific American,

Mar., 1949, p.31.

156. Forbes, R. J., Metallurgy in Antiquity, Brill, Leiden,

1950, p.442.

157. Conder, C. R., "The Canaanites," Transactions

of the Victoria Institute, London, vol.24, 1890, p.51.

pg.23

of 29 pg.23

of 29

Chinese Arrows as "Alkhatai,"

as we have seen. Forbes has held that the Hittites discovered

cast iron even before the Chinese did. If this is true, it is

possible the Chinese obtained their knowledge of it from the

Hittites.

China also led in the conquest

of the air. Francis R. Miller wrote that: (158)

China enters first claim to

the invention of the balloon � centuries before Europe knew

it. The Chinese further claim to have had a system of sigrnals

by which different toned trumpets sounded from the tops of high

hills and gave notice of impending changes of wind and weather,

for use by navigators of dirigible balloons.

Miller has given

an illustration from an official Chinese document of a large

dirigible said to have been used at the coronation of the Emperor

Fo-Kien, in 1306. It is large enough to carry 9 individual gondolas

lowered to the ground with pulley systems.

In another place, Miller has reported:

(159)

A contemporary of Confucius

(c. 550 B.C.) named Lu Pan who was known as the ''mechanician

of Lu," is said to have made a glider in the form of a magpie

from wood and bamboo which he caused to fly.

Miller also

stated that kites, as precursors of airplanes first appeared

in Chinese annals at a very early date. The Chinese who kept

the records frequently refer to them. The earliest kites were

used for military signalling, first recorded in warfare in the

time of Han Sin who died in 196 B.C. He was one of the Three

Heroes who assisted in founding the Han Dynasty. General Han

Sin, plotting to tunnel into Wei-yang palace, flew a kite to

measure the distance to it. (160) Needham wrote: (161)

De la Loubere saw the parachute

used by acrobats in Siam around 1688, and his description was

read a century later by Lenormand, who then made some successful

experiments and introduced the device to Montgolfier. This is

not to deny that the idea of the parachute had been proposed

in Europe at the time of the Renaissance, but there are Asian

references to it much earlier still.

The first suspension

bridges with iron chains were

158. Miller, Francis T., The World in the

Air,Putnam's Sons New York 1930, vol.1, p. 99.

159. Ibid., p.56.

160. Ibid., p.73.

161. Needham, J., Science and Civilization in China, Oxford,

1954, vol.1, p.231.

pg.24

of 29 pg.24

of 29

constructed in China

at least ten centuries or more before they were known and built

in Europe. (162)

The story of printing and of paper

manufacture is so well known as to need little consideration

here. It came to Europe first with the old camel silk trains

as a finished product, its secret of manufacture jealously guarded.

Not until an Arab victory over the Chinese armies near Samarkand

in A.D. 751, did paper settle in the West as an industry, set

up by captured Chinese paper makers. Its use soon spread all

over Europe.

The development of printing depended

upon the manufacture of suitable ink. We have already mentioned

the use of carbon black to strengthen rubber. This material was

first made by the Chinese, who prepared it by burning oil and

allowing the flarne to impinge on a small porcelain cone, from

which the deposited carbon was removed at frequent intervals

with a feather. The famous stick ink resulted from the compounding

of this with a strong glue solution. (163)

R. H. Clapperton has shown that

the recent researches of Sir Aurel Stein and Sven Hedin prove

beyond doubt that the Chinese vere not only the inventors of

rag paper, raw fiber (mulberry bark and bamboo paper), and paper

made of a combination of raw fiber and rags, but also the inventors

of loading and coating paper. (164) We formerly used a china-coated paper to obtain the

best reproduction of photographs with a fine screen, though this

has now been replaced with less expensive and possibly more durable

plastic coatings. But the idea originated with the Chinese.

A recent Chinese author, Li Ch'iao-p'ing,

points out that Chinese inventions opened up new fields of chemical

manufacture in early times, but then remained stationary for

centuries. One of their earlier contributions to medicine was

the extraction of ephedrine from the herb Ephedra, a process

credited to a very famous Emperor Shen Nung, who is supposed

to have lived somewhere between 3000 and 2200 B.C. (165) A two thousand year old

rig for drilling salt wells was recently cited as still a good

162. Ibid.

163. Stern, H. J., Rubber: Natural and Synthetic, Maclaren,

London, 1954, p.118.

164. Clapperton, R. H., and William Henderson, Modern Paper-Making,

2nd edition, revised, Blackwell, Oxford, 1942.

165. Bender, George A., Pharmacy in Ancient China, A History

of Pharmacy in Pictures, Parke Davis, and Co., no date.

pg.25

of 29 pg.25

of 29

model for the modern

cable rig of today's oil fields. (166) Even in the design of

clothing, they seemed to have a genius for hitting upon the best

end-results, quite apart from the actual materials they developed.

Thus it has been recently shown that the so-called "Chinese

sleeve" which permits each forearm to be inserted into the

opposite sleeve, is more effective for keeping the hands warm

in cold weather than either Arctic mittens or a muff. Europeans

adopted muffs and mittens. But having investigated the Chinese

pattern thoroughly, it now appears they are not as effective.

(167)

Although the "clock"

motor principle was taken to the Chinese from the West, their

water clocks long antedated the European systems of keeping accurate

time, and were certainly more dependable, especially when mercury

was used in place of water. The complexity of these water clocks

has only recently been recognized. Some ancient documents describe

them in sufficient detail to enable Needham and others to draw

plans and diagrams of their operation. This was reported recently

in the British journal, Nature. (168) These devices were highly ingenious, involving gear

trains of several kinds, the speed being very exactly regulated

by a very clever use of water or mercury. Knowledge of these

seems to have come into Europe during the Crusades. The clocks

were connected with astronomical observations, in an endeavour

to predict seasons more exactly. The interest was purely of a

practical nature.

As we have previously mentioned,

the Chinese had already discovered the uniqueness of finger prints,

and quickly perceived how useful this could be for identification

purposes. They were using them in the T'ang dynasty as early

at A.D. 618. (169)

According to a special report on

the use of natural gas, it is said that the Chinese were the

first to use it. (170)

The story goes that some villagers near Peiping were trying to

put out a local brush fire, when they found one flame that could

not be extinguished with water. "The practical villagers

then built a bamboo

166. See a review of "The Chemical Arts

of Old China," by Eduard Farber in Scientific Monthly,

June, 1949, p.430.

167. Annual Project Report (U.S. Quartermaster Stores) Jan.-Dec.,

1956, p.430.

168. Needham, J., and Wang Ling, and Derek J. Price, "Chinese

Astronomical Clockwork," in Nature, Mar. 31, 1956,

pp.600, 601.

169. Haddon, A. C., The History of Anthropology, Watts,

London, 1934, p.33.

170. Reported in The Telegram, Toronto, April 4, 1955,

in a special section devoted to the use of Natural Gas, under

the title, "Gas and Pipeline too: way back in 450 B.C."

pg.26

of 29 pg.26

of 29

pipeline from the outlet

to the village, and used the gas for heating brine to make salt."

This is said to have taken place somewhere about 450 B.C. Whether

they can be said to have invented the use of natural gas or not

is a questionable point, but certainly they were very quick to

see its practical possibilities. This is in exact contrast to

the Romans who produced cast iron in considerable quantities

but threw it all away because they did not recognize it as a

potentially useful product. (171) As we have already remarked, the basic technology

of all metallurgy is entirely non-Indo-European. Even heat-treatment

and case-hardening was known before we "discovered"

it. Some processes of steel production have seemed clearly to

be of our own devising, the Bessemer process, for example, which

is a means of producing particularly pure forms of iron in preparation

for the manufacture of certain types of steel. It has recently

been shown, however, that immediately before William Kelly introduced

the process into the United States, four Chinese workers were

brought in, presumably as experts.(172)

In some instances we not only never

have improved upon the products of our instructors, but actually

have not even been able to improve upon their methods of manufacture,

where we usually shine. Cire Perdu casting is still employed

for small bronze statues of racing horses and such items, and

even the use of cow manure for the mold has been retained from

the most ancient times, to give the best results. This system

is extraordinarily effective for casting hollow articles of intricate

form, where the use of ordinary cores is quite impossible, and

yet it is found in every primitive society that has any knowledge

of metals, in every archaeological site bearing the remains of

cultures who had developed metal casting skills, and virtually

every high civilization with the exception of Indo-Europeans

seems to have had a knowledge of the art � almost exactly

as it is now done in Europe. We therefore use the same basic

methods as non-Indo-Europeans for casting hollow objects in metal,

just as we have adopted exactly the same method of molding objects

in rubber (cored or slush-molded) as the natives of Central and

South America.

Although it will be possible to

quote authorities who do not hesitate to say in so many words

that we have invented virtually

171. Forbes, R. J., Metallurgy in Antiquity,

Brill, Leiden, 1950, p.407.

172. Needham, J., The Development of Iron and Steel Technology

in China, reviewed by F. C. Thompson, in Nature (England),

Dec. 12, 1959, p.1830.

pg.27

of 29 pg.27

of 29

nothing, such sweeping

generalizations need qualification. In the first place, racial

mixture has proceeded so extensively in Europe and America that

it is difficult to say who is truly Japhethic and who is a mixture

of Shem and Ham as well. It is no longer always clear who is

truly Indo-European ane who is not. But it is true to say that

whatever inventiveness we have shown in the past three or four

centuries has almost always resulted from stimulation from non-Indo-Europeans.

Our chief glory has been the ability to improve upon and perfect

the invenltions of othlers, often to such an extent that they

appear to be original developments in their own right. We can

also make some claim to have greatly advanced mass production

methods. But it would surely be a great mistake to credit the

improver with greater inventive ability than the originator.

Moreover, the individulal who tells the truth 99% of the time,

but now and then tells lies, would hardly be termed a liar. By

the same token, it does not seem proper to call a people "inventive"who

once in a while do invent something, but who 99% of the time

merely adapt the inventions of others to new ends.

Paul Herrman has written an interpretive

survey of man's conquest of the earth's surface from paleolithic

times to tle present day. It is the work of one man, no small

undertaking, and has therefore not the comprehensivenless one

might desire, but it has the advantage of being a unified treatment.

In his foreword he has this to say: (173)

A further aim in writing this

book was to weaken the very widespread conviction that our progress

in the technological aspects of civilization represents, in any

real sense, a greater achevement than tht of our forebears. The

liberation of atomic energy probably means no more and no less

than did the invention of the firedrill or the wheel in their

day. Both discoveries were of immense importance to early man.

Needllam says

that the only Persian invention of first rank was the windmill,

and apart from the rotary quern whose history is not quite certain,

the only European contribution of value, mechanically speaking,

is tge pot-chain pump. (174) This gives us two claims to originality. Compared

with the originality of other cultures prior, let us say, to

the 15th century A.D., we certainly did not shine in this direction.

Yet we have advanced technology so far ahead of all previous

civilizations that there must be some

173. Herrman, Paul, Conquest by Man.

Harper, New York, 1954, pp.xxi, xxii.

174. Needham, J., Science and Civilization in China, Oxford,

1954, vol.1, p.240.

pg.28

of 29 pg.28

of 29

fundamental reason � a reason to

be suggested in the Paper, "A Christian WorldView: The Framework

of History", Part V of

this volume.

Meanwhile, in the conquest of land,

sea, and air, in agriculture and animal husbandry, in economics,

trade, and commerce, in the creation of all that lies behind

literature, the keeping of records, and the ordering of knowledge,

in arts and crafts, in architecture, and the textile world, in

metallurgy and medicine, in the planning

of cities and the development of means of communication over

long distances, in the invention of tools and the exploitation

of power sources � in all these areas the foundations were

laid by Hamitic people.

What we have since been able to

do in elaborating this basic heritage is another story. It is

necessary here only to establish something of the measure of

our indebtedness. This catalogue by no means exhausts the list.

In fact, even in the use of electricity and internal combustion

engines of the Diesel type, the initial inspiration seems likewise

to have come from Hamites.

This Paper has

dealt with the contribution of descendants of Ham. The contribution

of Shem was of another very special kind, essentially in the

realm of the spirit. On the other hand, the contribution of Japheth

has been in the realm of the intellect. Japheth took the technology

of Ham and created science. But science unredeemed by a true

spiritual perception is far from beneficial for man in the long

run. Shem, Ham, and Japheth thus were each called to play a unique

and vital part. When any one of them has failed to contribute,

or when one has dominated the other two, civilization (though

seeming to gain at first) has always suffered a decline. But

when each has contributed in the proper measure, enormous strides

forward are made and the development of civilization has been

almost explosive. What, then, will world civilization become

when the Lord Jesus Christ returns to establish a Kingdom of

Righteousness in which not only the three sons contribute in

perfect proportion, but their contribution will be entirely for

peace and not for war? Surely this will be an age of wonders

indeed!

pg.29

of 29 pg.29

of 29  Copyright © 1988 Evelyn White. All rights

reserved

Previous Chapter *

End of Part IV * Next

Chapter (Part V)

Copyright © 1988 Evelyn White. All rights

reserved

Previous Chapter *

End of Part IV * Next

Chapter (Part V)

|