|

Abstract

Table of Contents

Part I

Part II

Part III

Part IV

Part V

Part VI

Part VII

|

Vol.2: Genesis and Early Man

PART I

FOSSIL REMAINS OF EARLY MAN

AND THE RECORD OF GENESIS

Table of Contents

Chapter 1. The Evolutionary Faith

Chapter 2. Faith Without Sufficient

Reason

Chapter 3. An Alternative Faith

Chapter 4. Where Did Man First Appear?

Publishing History:

1968 Doorway paper No. 45, published

privately by Arthur C. Custance

1975 Part I in Genesis and Early Man, vol.2 in The

Doorway Papers Series, published by Zondervan Publishing

Company

1997 Arthur Custance Online Library (html)

2001 2nd Online Edition (text corrections, design revisions)

pg

1 of 13 pg

1 of 13

Chapter One

The Evolutionary Faith

"Man is a primate and within the order of

primates

is most closely related to the living African anthropoid apes."

So wrote F.

Clark Howell recently, (1) providing us with a good example of the kind of confident

announcement with which evolutionary literature abounds. As it

stands, it is purely presumptive. Just because members of a family

are apt to look alike, it is not at all safe to assume that all

"look-alikes" are related. Howell's first statement

"Man is a primate" is true enough; but his second statement,

which is presented as though it were equally factual, is simple

supposition without any positive proof whatever. Within the order

Primates, man may most closely resemble living African anthropoid

apes from an anatomical point of view, but it is quite another

thing to state categorically that he is most closely related

to them. Resemblance and relationship are by no means the same

thing. Howell does admit in the next sentence that he is not

sure how far removed the relationship is, but the basic assumption

still remains that the blood relationship exists. Very few readers

except those expert in the subject would discern the presumption

in Howell's statement. All that the facts indicate is similarity.

Relationship is totally unprovable by an appeal to morphology.

If he had said, "Man is anatomically most like the African

anthropoid apes," his statement would have been quite correct.

As it stands, his statement is completely hypothetical. Howell

is confusing hypothesis with fact.

The extent to which anthropologists

today exercise faith, holding to be true and firmly established

what in fact is only hopefully believed, is borne out by several

of the following quotations, all of

1. Howell F. Clark, "The Hominization

Process" in Human Evolution: Readings in Physical Anthropology,

edited by N. Korn and F. Thompson, Holt, Rinehart and Winston,

New York, 1967, p.85.

pg.2

of 13 pg.2

of 13

which are from topflight

experts in the field. Raymond Pearl, for instance, said �

and this is a beautiful example of hopeful possibilities stated

by circumlocution as high probabilities: (2)

While everyone agrees that man's

closest living relatives are to be found in the four man-like

apes, gorilla, chimpanzee, orangutan, and gibbon, there is no

such agreement about the precise structure of his ancestral pedigree.

The evidence that he had a perfectly natural and normal one .

. . is overwhelming in magnitude and cogency. But exactly what

the individual steps were, or how they came about, is still to

be learned. There are nearly as many theories on the point as

there are serious students of the problem. All of them at present,

however, lack that kind of clear and simple proof which brings

the sort of universal acceptance that is accorded to the law

of gravitation, for example.

Only on one point, and that one

a little vague, can there be said to be general agreement. It

is that, on the weight of evidence, it is probable that at some

remote period in the past for which no clear paleontological

record has yet been uncovered, man and the other primates branched

off from what had theretofore been a common ancestral stem.

In this quotation

the phrase "a perfectly natural and normal pedigree"

means, of course, an evolutionary one. Pearl assures us that

the evidence for this is overwhelming in magnitude and cogency,

but in the next breath he speaks only of possibilities and adds

that even for these there is no clear paleontological evidence.

Many anthropologists today, twenty years after the above was

written, would argue that the paleontological evidence is now

at hand in the form of a wide range of catarrhine anthropoidea

loosely catalogued together as pithecines. These creatures include

such types as Dryopithecus, Ramapithecus, Kenyapithecus, and

of course the more popularly known Australopithecines. But a

study of the literature in which these fossils are described

indicates first of all that there is considerable disagreement

as to their precise status and relationship with one another,

and secondly, that there is considerable debate whether they

really stand in the line leading to Homo sapiens, though

people like Robinson hopefully try to slide them across in the

family tree so that they at least fall under the heading of hominoidea

from which man is supposed to have evolved. At the present moment

it appears to me that there has not been enough time yet to achieve

a clear picture, and even if evolution were true it still seems

unlikely that Homo sapiens arrived via a pithecine route.

The trouble is that the Australopithecines

had very small brains, a mean cranial capacity of 575 CC. (3) compared with the normal

2. Pearl, Raymond, Man the Animal,

Principia Press, Bloomington, Indiana, 1946, p.3.

3. Clark; Wilfred LeGros, "Bones of Contention," Huxley

Memorial Lecture, Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute,

vol.88, no.2, 1958, p.136-138.

pg.3

of 13 pg.3

of 13

for modern man of 1450

cc. and yet appear to have been tool users. Since by definition

man is a cultured animal and tools are an essential part of his

cultural activity, these primitive apes have been by some credited

with culture and for this reason elevated to manhood, though

at a very low level, of course. But there are many who hold that

a creature cannot be said to be a "cultured" animal

merely because it uses tools. Birds use tools for example, but

this can hardly be considered as cultural activity. (4) There is no unequivocal

evidence, that I am aware of, that the Australopithecines deliberately

manufactured tools. There is evidence of what looks like manufactured

tools, but it is highly debatable whether they were actually

the work of the Australopithecines themselves. It has been argued

that Australopithecines were hunted by early man and that these

tools were left by the hunters. W. L. Strauss Jr., (5) in a note appearing in

Science entitled "Australopithecines Contemporaneous

with Man?" said of these:

Some of these artifacts are

unquestionably worked, and all but one are composed of material

foreign to the site and the immediate vicinity � an indication

that they represent a true lithic culture. The stratigraphy seems

to make it clear that the artifacts are of the same age as the

red-brown breccia, and not intrusions. The industry is not of

the most primitive character. . . .

J. T. Robinson concludes that the

advanced character of this stone industry makes its attribution

to the Australopithecines dubious. . . . He believes that

the most reasonable hypothesis at the present time is to attribute

the industry to a "true man" that invaded the area

before the time that this particular red-brown breccia was formed.

In the second

place, it used to be held that cranial capacity and intelligence

were closely related. This is seriously questioned today although

there is general agreement that a human being cannot be normal

with a cranial capacity below about 800 cc., the so-called "cerebral

Rubicon" (6)

If there is no relationship between these

4. Tool Using: see Kenneth P. Oakley, "Skill

as a Human Possession" in A History of Technology,

edited by Charles Singer, E. J. Holmyard and K. R. Hall,

Oxford University Press, 1954, vol.1, pp.1-37 for a discussion

of animal tool-users. Also Mickey Chiang, "Use of Tools

by Wild Macaque Monkeys in Singapore," Nature, vol.214,

1967, p.1258, 9. Also K. R. L. Hall, "Tool-Using Performances

as Indicators of Behavioural Adaptability" in Human Evolution,

Readings in Physical Anthropology, edited by C. Singer, E.J.

Holmyard, K.R Hall, Holt, Rinhehart & Winston, New York,

1967, pp.173-210; especially p.195 in "Comments" for

a remark by R. Cihak: "The author states that not tool-using

but tool-making signalizes the critical stage in the transition

from ape to human; but it ought to be pointed out that tool-making

as 'shaping an object for an imaginary future eventuality,'

is the real boundary between ape and man." [his emphasis]

5. Strauss, W. L., Jr., "Australopithecines Contemporaneous

with Man?" Science, vol.126, 1957, p.1238.

6. Weidenreich, Franz, "The Human Brain in the Light of

Its Phylogenetic Development," Scientific Monthly,

vol.67, Aug., 1948, p.103-109. "Cerebral Rubicon":

P. V. Tobias, "The Old Olduvi Bed I Hominine with Specific

Reference to Its Cranial Capacity," Nature, 4 Apr.,

1964, p.3.

pg.4

of 13 pg.4

of 13

two indices, then the

very small Australopithecine brain might still qualify as "human."

But there is certainly no general agreement on the matter. In

any case, modern man with his far larger brain is represented

by fossils which were contemporary with the latest in the Australopithecine

line, so it still seems unlikely that Homo sapiens arrived

via this route.

Leaky, writing in 1966 with reference

to Homo habilis, a supposed maker of tools, for a number

of reasons rejects any such lineal series as Australopithecus

africanus � Homo habilis � Homo erectus

(the latter being essentially man as we now know him). . . .

(7) "It seems

to me," he said, "more likely that Homo habilis

and Homo erectus as well as some of the Australopithecines,

were all evolving along their own distinct lines by Lower Pleistocene

times." (8)

And again, "I submit that morphologically it is almost impossible

to regard H. habilis as representing a stage between Australopithecus

africanus and Homo erectus." He added:

I have never been able to accept

the view that Australopithecus represented a direct ancestral

stage leading to H. erectus, and I disagree even more

strongly with the present suggestion of placing H. habilis

between them. . . It is possible that H. habilis

may prove to be the direct ancestor of H. sapiens but

this can be no more than a theory at present. . . .

All that can be said at present

is that there was a time at Olduvai when H. habilis, Australopithecus

(Zinjanthropus) boisei and what seems to be

a primitive ancestor of H. erectus were broadly contemporary

and developing along distinct and separate lines [my emphasis].

The debate continues,

and though "no one" questions man's evolutionary origin,

the conclusive links are still missing.

The problem is that although there are

a substantial number of fossil candidates which can be manipulated

into the proper kind of sequence, the chain seems to lead rather

to modern apes or to extinction than to man. For certain periods

of geological history there are promising successions of fossil

forms which look as though they ought to lead to man, but they

don't. Recently, Elwyn L. Simons observed: (9)

7. Homo sapiens and Homo erectus are at least

contemporary and may quite probably have been one species according

to the latest studies made of the Talgai Skull by Anatomy Professor

N. W. G. MacIntosh of Sydney University, Australia, (Science

News, vol.93, Apr. 20, 1968, p.381).

8. Leakey, L. S. B., "Homo habilis, Homo erectus and THE

AUSTRALOPITHICINES", Nature, vol.209, 1956, p.1280,

1281.

9. Simons, Elwyn L. "The Early Relatives of Man," Scientific

American, July, 1964, p.50. Simons' recent discovery in the

Fayum of Aegyptopithecus reported in his article, "The Earliest

Apes" (Scientific American, Dec. 1967, pp.28-38)

and which he describes as "the skull of a monkey equipped

with the teeth of an ape," does not shed light on the nature

of the missing link between ape and man -- only between the monkey

and the ape.

pg.5

of 13 pg.5

of 13

Within

the past fifteen years a number of significant new finds have

been made. . . . The early primates are now represented by many

complete or nearly complete skulls, some nearly complete skeletons,

a number of limb bones, and even the bones of hands and feet.

In age these specimens extend across almost the entire Cenozoic

era, from its beginning in Paleocene epoch some sixty-three million

years ago up to the Pliocene which ended roughly two million

years ago. . . . But they do not lie in the exact line

of man's ancestry.

When the significance

of the data itself is a subject of so much debate, it is clear

that a great deal depends upon imaginative thinking, each authority

being persuaded that he is merely reading the evidence. But the

disagreement which exists between authorities demonstrates clearly

that the evidence can be "merely read" in several different

ways. For this reason, Melville Herskovits (10) observed that "no branch of anthropology requires

more of inference for the weighing of imponderables, in short,

of the exercise of scientific imagination, than prehistory."

Many years ago, Wilson D. Wallis

(11) pointed out

that there is a kind of law in the matter of anthropological

thinking about fossil remains which goes something like this:

the less information we have by reason of the scarcity and antiquity

of the remains, the more sweeping our generalizations can be

about them. If you find the bones of a man who has died recently,

you have to be rather careful what you say about him because

somebody might be able to check up on your conclusions. The further

back you go, the more confidently you can discuss such reconstructions

because there is less possibility of anyone being able to challenge

you. Consequently, when only a few fossil remains of early man

were known, very broad generalizations could be made about them

and all kinds of genealogical trees were drafted with aplomb.

A few wiser anthropologists today decry the temptation to draft

genealogical trees which, as I. Manton said, are more like "bundles

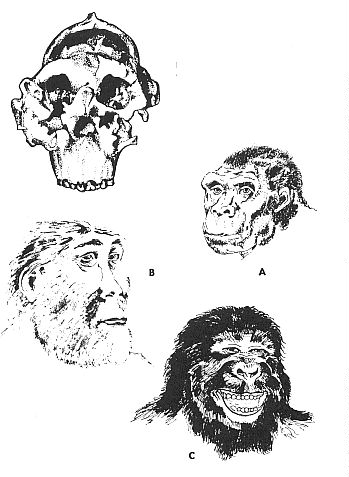

of twigs" rather than trees, in any case. (12) And when it comes to the reconstruction of a fossil

find into a "flesh-and-blood" head and face, the degree

of divergence can be even more extraordinary as is shown, for

example, in those concocted to represent Zinjanthropus for the

Sunday Times (London), the Illustrated London News,

and for Dr. Kenneth Oakley by Maurice Wilson, respectively.

(13) The reconstruction

of man's evolutionary history is still much more of an art than

a science. I have redrawn these three reconstructions from the

originals (see Fig.1 and 2)

10. Herskovits, Melville, Man and His Works,

Knopf, New York., 1950, p.97.

11. Wallis, Wilson D., "Pre-Suppositions in Anthropological

Interpretations," American Anthropologist, July-Sept.,

vol.50, 1948, p.560.

12. Manton, I., "Problems of Cytology and Evolution in the

Pteridophyta," Cambridge University Press, 1950,

quoted by Irving W. Knoblock, Journal of the American Scientific

Affiliation, vol.5, 3 Sept., 1953, p.14.

13. Sunday Times of April 5, 1964; and Illustrated

London News and Sketch, Jan. 1, 1960: see also "The

Fallacy of Anthropological Reconstructions," by the author,

Part V in Genesis and Early Man, vol.2 in The Doorway

Papers Series.

pg.6

of 13 pg.6

of 13

Top Left: The original fossil skull which formed

the basis of the three reconstructions of Zinjanthropus which

have been redrawn below: Zinjanthropus, as drawn (A) for

the Sunday Times of London, 5 April 1964; (B) by Neave

Parker for Dr. L. S. B. Leakey and published in the Illustrated

London News and Sketch, 1 January 1960; (C) by Maurice Wilson

for Dr. Kenneth P. Oakley. All these are redrawn by the author.

Top Left: The original fossil skull which formed

the basis of the three reconstructions of Zinjanthropus which

have been redrawn below: Zinjanthropus, as drawn (A) for

the Sunday Times of London, 5 April 1964; (B) by Neave

Parker for Dr. L. S. B. Leakey and published in the Illustrated

London News and Sketch, 1 January 1960; (C) by Maurice Wilson

for Dr. Kenneth P. Oakley. All these are redrawn by the author.

pg.7

of 13 pg.7

of 13

The principle that the less the data the more freedom

there is in interpreting it is widely recognized. In 1967 Takeuchi,

Uyeda and Kanamori, in speaking about the Theory of Continental

Drift, point out that "it often happens in science that

while data are scarce, interpretation seems easy, but as the

number of data grows, consistent argument grows more and more

difficult." (14)

Hallam L. Movius wrote very similarly in 1953 with reference

to Paleolithic cultures and the presently existing data with

which to reconstruct them. We now have so much more information

than previously that "we can hardly compose them into anything

even remotely approaching the ordered general scheme conceived

by the earlier workers." (15) I predict that when we have enough evidence we shall

find that the Biblical view of man's early history will not merely

prove to be precisely correct but will seem self-evidently so

to those who have that accumulated knowledge. In fact, they will

wonder why the truth was not more obvious to those who preceded

them. It is surprising how often a few additional facts act as

a catalyst that seems to jog everything suddenly into place until

one wonders how the truth could have been overlooked for so long.

Moreover, as has been recognized

for many years and emphasized very recently by J. T. Robinson,

(16) habits of

life, climate, and diet can tremendously influence the anatomical

features of the skull, indeed to such an extent that two series

of fossil forms which may in fact be a single species are by

some authorities put into different genera. I have in mind Australopithecus

and Paranthropus. How can one take seriously family trees in

which the lines of connection are drawn solely on the basis of

similarity or dissimilarity in appearance when these similarities

or dissimilarities could be nothing more than evidence of a difference

in diet? Such cultural or environmental factors cannot only cause

two members of a single species to diverge sufficiently to be

put into two different genera, but two different genera can for

the same reason converge until they have the appearance

14. Takeuchi, H., S. Uyeda, H. Kanamori, Debate

about the Earth, Approoch to Geophysics through Analysis

of Continental Drift, translated by Keiko Kanamori, Freeman,

Cooper & Co., San Francisco, 1967, p.180.

15. Movius, Hallam, "Old World Prehistory: Paleolithic,"

in Anthropology Today, edited by A. L. Kroeber, University

Chicago Press, 1953, p.163.

16. Robinson, J. T., "The Origins and Adaptive Radiation

of the Australopithecines," in Human Evolution: Readings

in Physical Anthropology, edited by N. Korn and F. Thompson,

Holt, Rinehart & Winston, New York, 1967, pp.277, 279, and

294.

pg.8

of 13 pg.8

of 13

of belonging to the same

species. There are some extraordinary examples of convergence.

(17)

There is another factor which may

very well have confused the issue, because it is possible that,

for reasons worth considering briefly, early man may have tended

towards the attainment of a certain "apishness" in

his appearance because of the great age to which he survived.

The Bible states categorically that men lived for centuries before

the Flood, and even after it. We have specific records in Scripture

of only a few people living for centuries after the Flood (Genesis

11:11�22), but it can scarcely be questioned that these individuals

were merely singled out because they were important for other

reasons. That many men besides them survived for centuries is

hardly to be questioned, though the life span of man declined

rather rapidly as generations succeeded one another after the

Flood.

Now one of the "findings" of

evolutionists is that certain animals may for obscure reasons

experience the persistence of a youthful form into adult life.

This is referred to technically as neoteny. The process leads

to an adult who, although strictly adult chronologically, is

nevertheless "immature" in form. Such individuals are

said to be paedomorphic. As an illustration, man is said to be

paedomorphic, for the following reasons and in the following

respect: Assuming that he is derived from some ape-like ancestor

who was covered with hair, it would be expected that he himself

would likewise be covered with hair. But the hairiness of the

adult ape is considerably greater than that of the newborn ape.

If the comparative hairlessness of the newborn ape were to have

persisted for some reason into the adult stage so that the full

grown creature was as comparatively free of hair as its young

is apt to be, then the adult would be termed paedomorphic, i.e.,

patterned (in this respect) like a child of its species. Since

man is comparatively hairless over the general body surface he

is believed to be paedomorphic, i.e., a hairy creature who didn't

quite produce the hairiness that was expected of him on the basis

of his ancestry. He has remained child-like, in this respect.

Sir Gavin de Beer is perhaps the

most suitable authority to whom to refer the reader on this subject.

(18) Neoteny refers

to a condition

17. Convergence: Leo S. Berg, Nomogenesis:

Or Evolution Determined by Law, translated from Russian by

J.N. Rostovtov, Constable, Edinburgh, 1926; David Lack, Evolutionary

Theory and Christian Belief, Methuen, London, 1957, p.65;

Evan Shute, Flaws in the Theory of Evolution, Temside

Press, London (Can.), 1961 pp.138ff.; and also Sir Alister Hardy,

The Living Stream, Collins, London, 1965, especially chapter

on Convergence, pp.138-146.

18. de Beer, Sir Gavin, Embryos and Ancestors, Clarendon

Press, Oxford, 1951, pp.52-68 and pp.88-100.

pg.9

of 13 pg.9

of 13

which is described as

being due to "a relative retardation in the rate of the

development of the body as compared with the reproductive

glands," so that the body does not run through so many stages

in the descendant as the ancestor did. Strictly speaking, paedomorphosis

refers to a situation where "the larva becomes precociously

sexually mature, whereas neoteny refers to a situation where

the adult animal retains larval characters." "The production

of phylogenetic change by the introduction into the adult descendant

of characters which were youthful in the ancestor" by means

of neoteny is termed paedomorphosis. Thus the comparative hairlessness

of man as an adult is considered to be a case of a hairy ancestral

ape being replaced by a hairl

ess descendant who is held to have retained to maturity the comparative

hairlessness of the ancestral infant.

The assumption is made,

further, that if man lived for a long enough time he would finally

in fact achieve a fully adult form. The trouble is he dies too

soon. In whatever way we may explain the fact that man's hairiness

increases with age, it is a fact. If therefore man were to live

for centuries it is conceivable that the developmental processes

which he shares to some extent with other living creatures of

a similar kind to himself might lead to a measure of convergence,

not because of any relationship but simply through great age.

If man lived to be hundreds of years old, and if the conditions

of his life led to his being forced to surrender some of the

mollifying influences of community life, so that he lived and

died as a hermit or an isolated family, it may very well be that

his remains, by their very unusualness, would confuse their finder

into supposing that he was not man in the undoing but ape-becoming-man.

Such great longevity might account for the comparatively large

numbers of weapons and artifacts which make up the substance

of prehistory but which are accompanied by so few skeletal remains.

A very small population of individuals could leave the remnants

of their settlements over tremendous territories if these individuals

survived for centuries. And it seems highly probable that greatly

extended experience through long years of trial and error would

tend to accelerate somewhat the processes of improvement so that

the progress from Paleolithic, to Mesolithic, to Neolithic could

easily occur in one generation, and Neolithic weapons might have

been used to kill Paleolithic Man as Dawson reported. (19)

It is evident, therefore, that

morphology in itself is not really any guide at all to lineal

relationships. Indeed, even the chance finding of the skeletons

of a mother and a child together, although

19. Dawson. Sir J. William, Fossil Men

and Their Modern Representatives, Hodder and Stoughton, London,

1883, p.123.

pg.10

of 13 pg.10

of 13

it may

be presumptive evidence of a mother-child relationship, could

never be taken as absolute proof. Almost all fossil remains are

"proved" to be related in this way only in the sense

that if you agree to the theory of evolution to start with, the

relationship might be reasonably assumed. But in itself, similarity

of form does not prove relationship. Those who see in their own

finds, or who wish to see in them, more of man than of ape tend

to classify them by tacking the suffix -anthropus on their

name. Those who re-emphasize rather the antiquity of their finds

tend to classify them as -pithecus. Thus there are two

alternative temptations, one being to stress the antiquity of

man's supposed ancestors, and the other the humanness of them.

Another factor clearly enters into these naming games and that

is the prestige of having made a find which initiates a new genus,

sub-family, or other category of some kind. Thus von Koenigswald

calls his Javanese find Meganthropus, whereas others see

it as merely representative of one branch of Australopithecines.

Similarly, Leakey labels his Olduvai finds as Zinjanthropus

whereas others would rob his specimens of their unique status

by reducing them also to a mere Australopithecine. (20) The unfortunate thing

is that the very naming of these finds can give to them a weight

of importance which can be quite unjustified. The name creates

the significance, not the find itself.

Sir Solly Zuckerman, (21) in a paper with the intriguing title, "An

Ape or The Ape," pointed out that far too much importance

tends to be attached to small differences between specimens which

but for these differences would certainly be classed as a single

species. His argument was that the study of modern apes, and

other creatures, demonstrates clearly and emphatically that within

a single family of apes or monkeys there may be individuals whose

divergence from one another is far greater than the divergence

which may be observed in two particular fossils that on that

account classified as not only belonging to a different species

but even different genera. To quote one of his opening passages:

Some students claim, or rather

assume implicitly, that the phyletic relations of a series of

specimens can be clearly defined from an assessment of morphological

similarities and dissimilarities, even when the fossil evidence

is both slight and noncontinuous geologically. Others, who in

the light of modern genetic knowledge are surely on firmer ground,

point out that several genes or several gene patterns may have

identical phyletic effects, and that when we deal with limited

or

20 Meganthropus: see G. H. R. von Koenigswald,

quoted by J. T. Robinson, "The Origin and Adaptive Radiation

of the Australopithecines" in Human Evolution: Readings

in Physical Anthropology, edited by N. Korn and F. Thompson,

Holt, Rinehart& Winston, New York, 1967, p.280; for Zinjanthropus:

see "The Fossil Skull from Olduvai," editorial comment

in British Medical Journal, Sept. 19, 1959, p.487.

21. Zuckerman, Sir Solly, "An Ape or The Ape,"

Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, vol.81,

1951, p.57.

pg.11

of 13 pg.11

of 13

relatively limited fossil materials,

correspondence in similar morphological features or in groups

of characters does not necessarily imply genetic identity or

phyletic relationship.

Zuckerman subsequently

quoted A. H. Schultz, one of the foremost students of the Primates,

as having said: (22)

Among several hundred

monkeys of one species, collected in the uniform environment

surrounding one camp in the forest of Nicaragua, were found specimens

with pug noses and those with straight profiles, some with large

ears and others with small ones. In short, they differed from

one another as widely as would an equal number of human city

dwellers and this in spite of the fact that these monkeys all

had the same occupation, the same diet, and the same climatic

conditions, and this during thousands of generations.

In 1943, Gaylord

Simpson had similarly written: (23)

Earlier paleontologists had

no real idea of the extent of morphological variation that can

occur in a single species... Workable criteria have only slowly

been achieved, hand in hand with similar work by neo-zoologists

and with experimental work. . .

It is conservative to guess that

among previously proposed species of fossil vertebrates, aside

from types of currently recognized genera, not more than a quarter

represent natural and distinct groups. The fraction of valid

species is probably much lower.

In spite of

these warnings it appears that minute differences in measurements

between this point and that or along some axis or other of a

fossil fragment that has already been distorted by its long burial

in the earth are made the basis of pontifical pronouncements

about the relationships and ancestral lines of potential candidates

for protohumanship. When Zuckerman presented his paper, he stated

specifically that he had in mind the current debates about the

Australopithecines and other African fossil primate specimens.

He argues such statements are of highly doubtful validity, and

these doubts extend with equal force to the estimates made of

cranial capacity. And with respect to dentition, he argues that

the impressive tables designed to illustrate relationships, or

otherwise, are fundamentally exercises "in dental anatomy,

not in primate phylogeny."

One thing is certain: no one is

ever tempted to make any pronouncement regarding their particular

finds which puts the slightest question mark against their evolutionary

origin. Evolution is unchallengeable. Nor does Zuckerman challenge

it.

LeGros Clark has pointed out that

"practically none of the genera and species of fossil hominoids

[and this includes all the Australopithecines according to Robinson]

which have from time to

22. Schultz, A. H., quoted by Zuckerman, ibid.,

p.58.

23. Simpson, G. G., quoted by Zuckerman, ibid., p.59.

pg.12

of 13 pg.12

of 13

time been created have

any validity at all in zoological nomenclature." (24) And again, (25)

Probably the one single factor

which above all others has unduly, and quite unnecessarily, complicated

the whole picture of human phylogeny is the tendency for the

taxonomic individualization of each fossil skull or fragment

of a skull by assuming it to be a new type which is specifically,

or even generically, distinct from all others.

In the popular

mind, the Australopithecines are constantly being presented as

though they were little by little filling the gap between man

and his animal ancestors, and the temptation has been for "fossil-finders"

to contribute to this confusion by attaching names to their finds

which are intended to reinforce this impression. (26) In point of fact, not

only are these names unjustified in many cases but the line itself

now appears to have continued its imagined evolutionary development

right up into Pleistocene times when modern man was already in

existence. This has the unfortunate consequence of making man

as old as his supposed ancestors, which seems nonsense to me,

but in the evolutionist's credo, this is his faith -- "the

substance of things hoped for, the evidence of things not seen.

. . ."

24. Clark, LeGros, "Bones of Contention,"

in Human Evolution:Readings in Phycsical Anthroplogy,

edited by N. Korn and F. Thompson, Holt, Rinehart & Winston,

New York, 1967 p.302.

25. Ibid., p.299f.

26. Thus Sir Solly Zuckerman, "Correlation of Change in

the Evolution of Higher Primates," in Evolution as a

Process, edited by Julian Huxley, A.C. Hardy, E. B.

Ford, Allen & Unwin, London, 1954, p.301. "The fundamental

difficulty has been that in the great majority of cases the descriptions

of the specimens that have been provided by their discoverers

have been so turned as to indicate that the fossils in question

have some special place or significance in the line of direct

human ascent as opposed to that of the family of apes."

pg.13

of 13 pg.13

of 13  Copyright © 1988 Evelyn White. All rights

reserved

Previous Chapter Next

Chapter

Copyright © 1988 Evelyn White. All rights

reserved

Previous Chapter Next

Chapter

|