|

About the Book

Table of Contents

Part I

Part II

Part III

Part IV

Part V

Part VI

|

Part VI: Cain's Wife: and the Penalty

of Incest

Chapter 1

Cain Marries a Sister

IN PRIMITIVE societies it is a general

rule that brothers do not marry their sisters. The strictest

of taboos are applied to this particular form of incest. Yet,

from certain points of view, close inbreeding -- especially within

a family of prominence -- has something to commend it when considered

from the social and economic point of view: both material wealth

and wealth in the form of rights or privileges are by this means

kept closely within the family. An excellent example of this

was to be found among the Incas, where the right to marry within

the clan, and indeed to any who were first degree relatives,

was reserved for the chiefs primarily to protect the interests

of the royal house. According to Felip Huaman Poma de Ayala in

his El Primer Nuevo Chronica Y Buen Gobierno, published

in Paris in 1926, the formal Inca statement was: (1)

We, the

Inca, order and decree that no one shall marry his sister or

his mother, nor his first cousin, nor his aunt, nor his niece,

nor his kinswoman, nor the godmother of his child, under penalty

of being punished and of having his eyes pulled out . . . because

only the Inca is allowed to be married to his carnal sister.

. . .

In "modern" times the maintenance

of rights within a family by this means is best exemplified in

the royal families of Europe, the right in this instance being

the right of holding dominion rather than material wealth per

se -- since many royal families are impoverished. But as

is well illustrated in the case of the Spanish royal family,

close inbreeding has had a very deleterious effect. Charles Blitzer,

writing of this family, spoke of Charles II in the following

way: (2)

1. Felipe de Ayala: quoted

by Victor W. von Haggen, Realm of the Incas, Mentor Books,

New York 1957, p.125

2. Blitzer, Charles; "The Age of the Kings," in Great

Ages of Man, Time Inc., New York, 1967, p.168.

pg

1 of 16 pg

1 of 16

Charles

II of Spain, the most grotesque monarch of the seventeenth century,

had been a travesty of a king. Generations of royal intermarriage

had culminated in Charles in a creature so defective in mind

and body as to be scarcely even a man. He was born in 1661, the

product of his father's old age, and his brief life consisted

chiefly of a passage from prolonged infancy to premature senility.

He could

not walk until he was ten, and was considered to be too feeble

for the rigours of education. In Charles, the famous Hapsburg

chin reached such massive proportions that he was unable to chew,

and his tongue was so large that he was barely able to speak.

Lame, epileptic,

bald at the age of 35, Charles suffered one further disability,

politically more significant than all the rest: he was impotent.

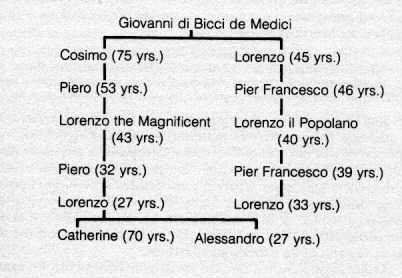

The Medici family -- beginning with

Giovanni di Bicci de Medici (1360-1429) and ending, in one line,

with Catherine de Medici (1519-1589) who married Henry II of

France -- provides us with another instance where inbreeding

clearly affected viability. The members of the family for successive

generations traced through two lives lived shorter and shorter,

with the notable exception of Catherine herself. These two lines

are given below with their life spans indicated by years rather

than dates, to simplify the figures (3).

3. Hale, John R, "The

Renaissance," in Great Ages of Man, Time Inc., New

York, 1965, p.165.

pg.2

of 16 pg.2

of 16

Other branches of the family seemed to have done very

much better, a fact which suggests that marriages further afield

led to the birth of quite normally viable offspring.

While it is customary to assume

that close inbreeding has always a damaging effect, this

is not strictly true -- as is evident in the case of the Inca

rulers, whose royal prerogative it was to marry sisters. Indeed

there could conceivably be a connection between a ruling house

and incestuous marriage, for genetic reasons. In antiquity and

during periods when ruling houses were first establishing themselves,

only such families as produced a line of particularly energetic

and forceful individuals would be likely to come to power. It

might very well be evidence of exceptional breeding (in the genetic

sense) that a line could survive the potential hazards of inbreeding

such as are involved in a series of brother-sister marriages.

That a particular "house" could so inbreed successfully

might quite rightly establish that house as an exceptional one

from the genetic point of view. A Royal House may therefore have

been any house which could successfully mate in this incestuous

way and not witness any ill effects, while at the same time accumulating

and consolidating its wealth and prestige.

At any rate, the Incas were a notable

royal house and certainly practiced incest over a considerable

number of generations without ill effect. As Murdock said: (4)

The long

line of Inca emperors reveals only one man of mediocre talents;

all the rest displayed exceptional energy, resourcefulness, tolerance,

and magnanimity in the conduct of affairs. Certainly no dynasty

with a higher average order of capacity has graced a throne in

the whole of human history.

It is well known that the Ptolemies

also married their sisters in order to maintain the integrity

of material wealth and rights, and the experiment was not without

success if Cleopatra is any indication. This notable woman represented

the seventh generation of such brother-sister marriages. There

is some evidence, I believe, that her young brother was showing

signs of mental deficiency, a circumstance which, if it is true,

might be an indication that the inbreeding process was just beginning

to break down and the line was at the end of its genetic good

fortune.

Other royal families, the Alii

among the Hawaiians, for example, and the Singhalese (5)

must be counted among those who practiced this principle of brother-sister

marriages. Against this background

4. Murdock, George P., Our

Primitive Contemporaries, Macmillan, New York, 1951, p.417.

5. Alii of Hawaiians: according to Dr. Gorden Brown, Dept. of

Anthropology, University of Toronto; Singhalese: Edward B. Tylor,

Primitive Culture, Murray, London, 1891, vol. 1, p.50.

pg.3

of 16 pg.3

of 16

one may

remember that among the common people such marriages were taboo.

Primitive people are highly observant and quickly learn to avoid

doing things which reduce the viability of their community as

a whole. Experience taught these that the children of brother-sister

matings were in one way or another apt to be less healthy than

the children of those who married more distant relatives.

But it seems likely that these

people also observed rather quickly that the wealth of a family

was dissipated when the various children married at too great

a distance in terms of blood relationship. Hence almost all such

people laid down rules which, while forbidding marriage to a

brother or a sister, also frowned on marriage to anyone who was

only remotely related; in the latter case, the bride price paid

by the groom or the dowry brought by the bride tended to pass

out of the family's control. They therefore bracketed the range

of relationship within which one might marry, avoiding the extremes.

Indeed, in most cases the relationship considered ideal was the

marriage of cousins, a practice almost universal among primitive

people.

Now, the judgment made by the general

public in such a case might very well have been firmly founded

upon fact: namely, such a family was, in their genetic makeup,

truly an outstanding one. This observation makes perfectly good

sense when it is realized that through the centuries we have

accumulated individually so much low-grade genetic material that

when brothers and sisters marry, the same particular kind of

low-grade material finds expression in the offspring in a reinforced

way, in a way which will be examined a little more fully subsequently;

the end result is that such children are apt to be much below

average in many different ways. As we shall show, experience

fully bears this out, and theory has reached such a point of

refinement that geneticists can often predict quite accurately

the degree of probability of detrimental traits that will appear

in such children. Thus, when brothers do marry sisters without

such deleterious effects, we have to all intents and purposes

good evidence that quite by chance they have inherited a less

damaged genetic constitution.

Although I do not have available

all the information that would be required to substantiate what

I wish to propose below, I think we may well have in recent times

a good illustration of these general principles. I have in mind

a very primitive people in South India known as the Toda, (6)

who practice polyandry -- that is, several men

6. Murdock, George P. ref.

4. p.106.

pg.4

of 16 pg.4

of 16

(normally

brothers) share one woman who becomes wife to them all. In writing

of these people, George Murdock referred to them as a "race

of superb men and hideous women." Elie Reclus, in his work

on comparative anthology titled Primitive Folk, also refers

to the splendid character (within the context of their culture)

of Toda males. And he added this remark, which is apropos: (7)

Marriage

between relatives has had no dire consequences in this tribe,

which, though it has practiced the closest endogamy (marriage

within the family) for centuries, possesses an athletic constitution

and pleasing exterior, and is famed for the gentleness of its

manners, and the peacefulness and tranquillity of its way of

life.

Although

toward the end of the last century the Toda were apparently beginning

to decline as a consequence of their contact with more highly

civilized people and the breaking up of their own native customs,

we have sufficient evidence from the studies of W. H. R. Rivers

and others that close intermarriage had not proved detrimental

to these people in the way that it habitually does among other

peoples, whether primitive or highly civilized. Some fortuitous

circumstance had therefore preserved among these people a genetic

strain less damaged with the passage of time than most of us

share. It is apparent, therefore, that not only so-called royal

families but even whole tribes may closely intermarry with impunity

upon certain occasions, while others cannot do so without disastrous

results.

Let us therefore examine the factors

which determine when brother-sister marriages will be harmful

and when they will not: and in what form the degeneration is

likely to show up. And let us consider why this effect results.

It will be necessary to attempt to do this without becoming too

involved in the jargon of the geneticists; thus some statements

may be somewhat unsatisfactory from the point of view of the

experts, an ever-present danger when oversimplification is required.

Inherited Potential

When

a man and a woman are mated, each passes onto their children

one half of the inherited potential they themselves have received

from their parents. Present indications are that the characteristics

which each will contribute to the child are carried by genes.

For each character that a man or a woman may contribute to his

offspring, there are usually two alternatives -- or to put it

another way, the potential is in duplicate and at the present

moment chance appears to govern which of the two alternative

contributions the

7. Reclus, Elie, Primitive

Folk: Studies in Comparative Ethnology, Scott, London, no

date, p.200

pg.5

of 16 pg.5

of 16

individual

will pass on. For example, a brown-eyed parent may pass on to

his children that which will give them blue eyes instead of brown

eyes like his own.

There are a very large number of

alternatives, as for example the control of hair colour (fair

or dark). Modern research into the nature of these controlling

genes (and there are thousands of them in each individual) has

shown that for one reason or another, these genes get damaged

and appear in a condition which is called mutant. Normally a

gene once mutated remains mutated, i.e., damaged, as it is passed

through each successive generation. The inevitable conclusion

of this finding is that the amount of material controlling inheritance

becomes increasingly damaged in its nature with each successive

generation. In other words, each generation may be expected to

be less viable in some way than the preceding one, even though

the damage may be so small as to be, to all intents and purposes,

of little consequence.

Now, if a parent with a particular

damaged gene complex passes onto a son and a daughter this damaged

material, these offspring will both share damage at the same

point (or locus) in their own gene complexes. Should these two

marry, in their mating the particular segments of damaged material

are bound to be brought together in a way that enormously reinforces

their power to effect the growing embryo detrimentally. On the

other hand, if such a son marries a girl from some other family

who, although suffering genetic damage like the rest of us, has

not inherited damage at the same place in the gene chain, the

effect of bringing the two "damages" together is likely

to be much less serious, for the areas of damage do not coincide.

For this reason, marriages are safer from the physiological point

of view when the two parties do not share the same kind of damage

in their genetic make-up at the same locus.

At the beginning of this grossly

over-simplified statement, I said that the amount of damaged

material increases with each generation. It follows logically,

therefore, that each previous generation has suffered less genetic

damage. We can extrapolate backward in time until we begin to

reach a point at which damage to the genetic material would be

vastly less than it now is: logically, if we go back far enough,

it would not exist at all. It is true that this may not be a

straight line function, that the improvement in reverse may follow

a curve which slows up in its approach to perfection and never

quite reaches it. This is possible. There is no need to make

this assumption, however. There is no reason at all why the first

human beings may not have had a perfect constitution, in which

case brother-sister marriages at the time would be absolutely

harmless.

pg.6

of 16 pg.6

of 16

Before we return once more to this aspect of the paper,

let us look briefly at some of the present evidence for the detrimental

effect of close-relationship marriages. The underlying causes

for the deleterious effects of incestuous matings are pretty

well understood and have been variously expressed. For those

who have some knowledge of and interest in the more basic principles

of human genetics, the following miscellany of quotations will

perhaps be of value and, taken as a whole, state the case clearly

enough. For example, Bentley Glass, in a paper which gives some

consideration to the possibility of "improving" the

human stock by inbreeding in the way this is done with plants,

made the following observation: (8)

Within

the past three centuries human populations have increased enormously

in size, and an approach to panmixia has become characteristic

of the major races of the world population. The result of this

has been to render man a highly heterozygous animal. Beneath

the facade of dominant traits expressed in the phenotype of each

individual, there lies concealed a great number of unmanifested

recessive genes, kept in a heterozygous condition within the

population. From studies of mutation in man, mouse, and Drosophila

it is apparent that the manifestation of the majority of

these recessives would be deleterious in most, if not all, environments.

In fact, one quarter to one third of them are lethal when homozygous.

New lethal and deleterious mutations

arise in each generation at an average frequency that is estimated

to be of the order of 1 in 100,000 per locus per gamete, or higher.

The number of different genes (i.e., loci) in man may be taken

as 10,000 or perhaps even 40,000. It follows that at least one

gamete in ten will bear a new mutant, nearly always of a lethal

or detrimental sort. The effect of these is not normally evident,

since they are kept heterozygous. Any return of the human population

to closer inbreeding may be expected to bring these recessive

traits to the surface. . . .

Human pure lines selected for (say)

intelligence would most probably be weak in vigour, low in fertility,

and beset by numerous hereditary defects.

From

a mathematical point of view, the situation may be put in this

way: matings among first cousins (as in Darwin's case, for example,

or his sister Caroline's case) result in the offspring having

identical genes in a ratio of 1 to 7. (9) Many of

these genes will be recessive mutants and therefore detrimental

to the possessor when inherited homozygously. Mating of uncle

to niece, or nephew to aunt, raises this ratio to 1 to 3. Matings

among brothers and sisters raises this ratio, often disastrously,

to 1 to 1.

Willard F. Hollander,

in an article significantly title, "Lethal Heredity",

commented on this situation as follows: (10)

8. Glass, Bentley, "A

Biologic View of Human History," in Scientific American,

Dec., 1951, p.367.

9. Darwin's family: see Donald W. Patten, The Biblical Flood

and the Ice Epoch, Pacific Meridian Publishing Co., Seattle,

I966 , p.244, fn.16.

10. Hollander., Willard F.; "Lethal Heredity," in Scientific

American, July, 1952, pp.59-60.

pg.7

of 16 pg.7

of 16

Sometimes a mutation is so radical that nothing

can be done to prolong the animal's life to maturity. This is

what is known as a lethal mutation. Often it kills the animal

while it is still an embryo. Most lethal mutations are recessive,

however, and are carried unsuspected by normal appearing animals.

. . .

The quickest way to expose lethal

traits is by intense and continued inbreeding. In man such matings

are generally illegal or tabu; the experience of the race indicates

bad results . . . the outcome is generally detrimental. When

inbreeding begins, the heredity seems to be breaking down. All

sorts of defects and weaknesses appear. The average life span

decreases. After a few generations the family often becomes extinct.

We shall have occasion to return to

this latter aspect of the problem, but we may just note here

Hollander's conclusion: (11) "The abundance of hidden lethals

and hereditary defects exposed by inbreeding must be seen to

be believed. It seems safe to say that very few individuals of

an ordinary mixed population fail to harbor one or more. Whence

came this multitude of skulking malefactors?" To this last

point we must likewise return subsequently, for the perceptive

reader may already have noticed that animals are afflicted with

these imperfections as well as man and they cannot therefore

be attributed in a direct way (at least insofar as animals are

concerned) to a fallen nature. The fall of man may be the originating

cause, but this cause cannot be applied directly to animals

unless animals are included among sinners -- though Scripture

has intimations even for

this. . . . (12)

Under normal circumstances inbreeding,

therefore, leads to a decline in overall vigour for a number

of generations. In many cases the detriment is so severe that

the line becomes extinct. However with very careful management

such inbred lines, if they can be preserved through ten or

twelve generations, tend to settle down in a modified

form, i.e., with a somewhat different character. This different

character may turn out to be a desirable one from the breeder's

point of view, having lost certain of its former strengths and

11. Ibid., p.60.

12. The wording of Genesis 3:14 ("above all cattle . . .")

may quite justifiably be taken to imply that other animals for

some reason were involved in this judgment, a conclusion which

would presuppose at least some moral responsibility on their

part. It could be argued that in Jonah 3:8 it is assumed that

the animals were partly involved in Nineveh's wickedness, the

animals also being dressed in sackcloth. The lamb for the sacrifice

on the Day of Atonement was to be a lamb of the first year, which

again might suggest something analogous to an "age of accountability."

The ox that gored a man was to be stoned to death, not merely

slaughtered. It is conceivable that this was merely to punish

the owner by rendering the slaughtered animal unfit for food,

since it would not be properly bled: and the hide itself would

probably be marred. On the other hand, it might be argued that

the ox itself was being punished. Such passages as these are

certainly not unequivocal, but they provide interesting possibilities

for further discussion.

pg.8

of 16 pg.8

of 16

accumulating

many new weaknesses, but having also acquired some new quality

which the breeder had particularly in mind. This is true of corn,

for example. (13) If the inbreeding can be arranged

from widely separated lines, the hybrids generally turn out to

be more vigorous. This sounds like a contradiction. What is actually

meant is that -- by inbreeding one line in one geographic locality

until it is highly degenerate and perhaps barely surviving, and

at the same time inbreeding another line in another geographic

location until it too is degenerate -- if the two inbred degenerate

lines are now crossed, the resulting breed may be more vigorous

than it would have been if the originals had merely been crossed

without first producing the degenerate types. It is not necessary

to go into the causes of this somewhat odd but most useful discovery,

it is necessary only to include it in this discussion because

one commonly hears the statement made that inbreeding produces

superior stocks. This is true of plants and of some animals,

and it is conceivable that it might be true of human beings.

But in the process, the lines degenerate seriously or may die

out completely.

On the basis of this theoretical

understanding of what is happening, it might be supposed -- and

the supposition is borne out by experience -- that in a small

population which is multiplying there may appear at first an

extraordinary diversity of types. Not all mutations expressed

homozygously are lethal, but they are all likely to be more or

less effective in substantially modifying the bearer's physical

type. As Lebzelter pointed out, a small group of people will

share a basically homogeneous culture but show great physical

diversity, whereas a larger community of people (because mutant

genes are less likely to appear homozygously) will show greater

uniformity of physical type but allow a larger measure of cultural

variability. (14) This may very well account for the

fact that early man seems to have proliferated types (forerunners

of races) in a remarkably short time while at the same time witnessing

an amazing measure of cultural conformity. This heterogeneity

of physical type appears even within single families, as for

example, in the Upper Cave at Choukoutien. (15) Early

human history may have quickly witnessed the emergence of all

the racial types which we now think we can recognize in the modern

world. There is no need to postulate tremendous eons of time.

I prefer the word emergence: most people

13. Inbreeding of corn: Gordon

W. Whaley, "The Gifts of Hybridity," in Scientific

Monthly, Jan., 1950, p.12.

14. Lebzelter Viktor, Rassengescichte de Menscherit, Salzburg,

1932, p.27. University of Chicago Press, 1948. p.80.

15. Choukoutien diversity : see Franz Weidenreich, Apes, Giants,

and Man, University of Chicago Press 1948, p.86.

pg.9

of 16 pg.9

of 16

would

prefer the word evolution, and on the basis of the above

reasoning they would say, as Franklin Shull said, (16)

that "if a population is very large . . . evolution

must be slow under these circumstances," and on the other

hand if the population is too small and inbreeding too frequent,

the population is likely to die out, being overwhelmed by its

own defects. Several royal families have suffered virtual extinction

by this very process, and all because they sought to preserve

family lines intact.

In some parts of the world there

are isolated communities in out-of-the-way villages, even in

otherwise densely populated areas in which inbreeding has proceeded

for many years. In such communities there is a high incidence

of deaf-mutism. W. L. Ballinger reported in one case that forty-seven

marriages between blood relatives produced seventy-two deaf-mutes.

(17) In the same connection E. B. Dench remarked, "Consanguinity

of the parents is among the most common causes (of diseases in

the ear), and the great frequency of deaf-mutism among the inhabitants

of mountain districts is probably to be explained by the fact

that intermarriages are much more common among such people."

(18) Similarly in Lajous' Analytical Cyclopedia of

Practical Medicine, it is noted that "several statisticians

have proved that the closer the degree of relationship between

parents, the larger was the number of deaf-mutes born."

(19)

In The Lancet, a discussion

was reported on the risk taken by parents who decide to adopt

a child born of an incestual relationship It was observed that,

(20)

. . . medical practitioners are sometimes asked about the

advisability of the adoption of a child born as the result of

incest. Such children will have an increased risk of being affected

by recessive conditions. In order to get an estimate of the extent

of this risk, in 1958 I invited Children's Officers to let me

know prospectively of pregnancies or of new births in which it

was known that the pregnancy or birth was the result of incest

between first degree relatives.

These children were followed prospectively

and anonymously through the Children's Officers. The children

were known to me by number and correspondence referred only to

the child's number. Thirteen cases of incest (6 father-daughter

and 7 brother-sister) were reported to me in 1958 and the latest

information on them was in midyear 1965 when the children were

all 4 to 6 years old. I summarize here the information on these

13 children.

16. Shull, Franklin, Evolution,

McGraw-Hill, New York, 1936, p.146.

17. Ballinger, W. L.,

Diseases of the Nose, Throat, and Ear, Lea and Febiger, Philadelphia,

8th edition, p.823.

18. Dench, E. B., Diseases of the Ear, Appleton, New York,

1921, p.694.

19. Lajou, Analytical Cyclopedia of Practical Medicine, p.450:

the documentation is unfortunately incomplete.

20. "Risks to Offspring of Incest," in The Lancet,

London, Feb. 25, 1967, p.436.

pg.10

of 16 pg.10

of 16

Three children

are dead: one at 15 months of cystic fibrosis of the pancreas,

confirmed at necropsy; one at 21 months of progressive cerebral

degeneration with blindness; and one at 7 years, 11 months of

Fallot's Tetratology (this child had an IQ of 70). One child

is severely sub-normal, with much-delayed milestones, and was

considered non-testable at age 4 years, 9 months, when she had

a vocabulary of only a few words. Four children are educatively

subnormal; the known IQ of 3 are 59, 65, and 76. The remaining

5 children are normal.

The risk of parents sharing a recessive

gene will be four times greater in cases of incest between first

degree relatives than it would be between first cousins.

So

much, then, for the evidence. Incest today is clearly detrimental

in a very large percentage of cases, the risk of defective

offspring being so high that every civilized country legislates

against the marriage of brothers and sisters. Yet it is a risk

rather than a certainty, an important fact which shows that under

certain circumstances it might be quite safe -- though the circumstances

under which such a union could be predicted safe are not known

at present. Current genetic theory does, however, indicate that

the number of recessive and damaged genes increases rather than

decreases with each generation. It might be thought that if there

is a steady increase, the complement of genes in each individual

would be by now all damaged in one way or another. Indeed, if

the factors which lead to such damage (certain types of natural

and artificial radiation and some poisons, and so forth) have

always been with us -- a fact which seems likely enough for a

very large part of human history -- and if current theory about

the vast antiquity of man are really sound (which I don't believe

they are), one would have to suppose that the damaging process

must by now have almost completed its task. But evidently, even

in comparatively recent times, this is not the case, for as we

have already noted, both Hawaiian and Incan chiefs successfully

married their sisters, and somewhat before that the Ptolemies

did so.

It seems to me, therefore, that

the evidence does not on the face of it bear out the concept

of man as already having thousands of successive generations

behind him. The biblical record actually shows only 77 generations

from Adam to Christ, (21) and if we add to this the two thousand

years since, we have something like 100 to 120 generations covering

the whole of human history. Since the accumulation of defective

genes is meaningful only in terms of their effect on succeeding

generations, it is not altogether unlikely that the first human

beings (namely, Adam and Eve) were indeed perfect, and

21. See "Genealogies

of the Bible," Part V in Hidden Things of God's Revelation,

vol.7 of The Doorway Papers Series.

pg.11

of 16 pg.11

of 16

that

the damage started to be done following the Fall and has accumulated

ever since at what seems to be a reasonable rate during these

120 generations, until we reach the present situation in which

there are still some possibilities of successful brother-sister

matings, though the odds are against it. At the rate at which

these mutations occur in each generation, according to current

genetic theory, one would not expect to find any undamaged segments

of the individuals inherited stock of genes if the human race

had been multiplying for thousands upon thousands of generations.

We would all be so badly damaged by now that no brother-sister

marriage could possibly succeed any longer.

On the other hand, taking the biblical

story as it stands, Adam's sons and daughters (Genesis 5:4),

of whom Cain was one and his wife another, need not have been

carriers of any more than a mere token of damaged genetic stock.

Such a marriage need not have endangered the offspring.

There is, surprisingly enough,

direct evidence in Scripture that this interpretation of the

events is strictly true. We are first of all presented with a

list of immediate descendants for some ten generations from Adam

to Noah who enjoyed what must be described as magnificent viability.

Consider for a moment what was happening during this period of

time. Prior to the Flood, man may well have been shielded against

at least one source of danger to the genes, namely, cosmic radiation,

by the existence of some kind of barrier in the upper atmosphere.

There are many who believe that this barrier disappeared at the

time of the Flood and could indeed have been related to that

event. The pre-Flood population (both men and animals,

be it noted) may therefore have suffered little damage to

their genes throughout each succeeding generation while these

environmental conditions existed.

Added to this is the fact that

the population was multiplying during this time so that, even

if some damage was occurring, it would become less and less necessary

for any man to marry a near relative, thereby avoiding any reinforcement

of such gene damage. For this reason, there is little or no evidence

that man, physiologically considered, was becoming an inferior

creature -- at least, insofar as his inherited vigour was concerned:

and the same may well have applied to the animal world.

But then came the Flood, which

reduced the world's population to eight souls, all of whom had

now accumulated some damaged genes and were also first-degree

relatives, i.e., Noah and his three sons. The sons and daughters

of the next generation would therefore

pg.12

of 16 pg.12

of 16

be also

marrying near relatives, and one could only expect as a consequence

that evidence of decreased viability would begin to show up,

while the potential hazard from cosmic radiation would greatly

increase. This could be the answer to Hollander's final query:

inbreeding of a greatly reduced population, and exposure to cosmic

radiation at a new level -- both as a consequence of the Flood.

This is, of course, precisely what did happen and precisely at

a rate commensurate with the discovery of modern genetics resulting

from experimental inbreeding. Within ten generations (compare

Glass's figures) the life span of post-Flood individuals, insofar

as they are represented by those whose ages are given in the

Bible, had rapidly declined until it was only about one eighth

of the pre-Flood period, thereafter slowly leveling off first

to 120 and later to three score and ten. (22)

All this makes perfectly good sense

and accords very satisfyingly with modern findings, provided

that one accepts the whole biblical record just as it stands.

It

has been proposed by some who have due regard to the Word of

God that Cain married the offspring of some other human creatures

who were not descendants of Adam. (23) They argue

this on the ground that Cain would not have expressed any fear

of being killed by people who might find him unless there really

were people outside his immediate family in Adam. But this assumption

need not be made at all, because Cain would not necessarily have

knowledge of whether there were or were not other people in the

world; even if he had never seen any, he might very well suppose

that there were, the supposition being all that was needed to

make him afraid. He was simply a man living in fear of suffering

at someone else's hand what he had caused his brother to suffer.

He had no way of knowing whether there were or were not other

people in the world: his conscience served to people it even

if no other people had existed.

At the same time, very serious

theological problems would arise if Cain had married outside

the family of Adam, since his children and his descendants would

no longer be strictly "in Adam." This difficulty has

been met by some writers by proposing that the Flood destroyed

all except those who belonged to Adam's family. It is possible,

of course, that this is so, but this vast population must still

presumably come to the judgment with all those whom the

Flood destroyed, and how then will they be judged? It does not

appear to

22. 0n this see "Longevity in Antiquity

and Its Bearing on Chronology," Part I

in The Virgin Birth and the Incarnation, vol.5 of The Doorway

Papers Series.

23. See the next chapter,

"Was Cain's Wife of the Line of Adam?"

pg.13

of 16 pg.13

of 16

me that

the Bible allows for such a contingency. As I see it, the redemption

that is in Christ was as applicable to Adam and Cain and all

the rest of the patriarchs as it is to ourselves. Would we not

then be faced with a kind of half-applicability to Cain's children,

and a quarter-applicability to his grandchildren, and so on as

the line was diluted -- until there is no applicability at all?

The very statement of the situation itself points up the theological

problem that such a circumstance would bring about.

To some extent the above interpretation

of the identity of Cain's wife has been held as an accommodation

to anthropological theory which postulates sub-humans and near-humans

at a period in time far antedating the "traditional"

date for the creation of Adam. I do not know the answer to the

present conflict between secular and biblical anthropology, although

I am sure we shall see the answer in due time: but I believe

that the Bible itself has gone out of its way to try to make

it clear that Adam really was the only man at the time

of his creation and Eve the only woman at the time of her formation.

Genesis 2:5 tells us that there was not a man to till the ground.

Genesis 2:18 tells us that Adam was quite alone and that this

was not good for him. Then in Genesis 2:20 we are told that although

God brought creatures to Adam who might have been a potential

mate for him, there was not found one that was suitable. Finally,

as though the point had still not been made quite clear, we are

told in Genesis 3:20 that Eve became (so the Hebrew) the

mother of all living.

Almost any one of these statements

by itself might be thought by some people sufficient to settle

the issue. But surely their cumulative effect is about as conclusive

as to the intent of Scripture as any such series of statements

could possibly be. I believe, therefore, that the only position

one can reasonably take in the matter of Cain's wife is that

she was one of Adam and Eve's daughters, i.e., a sister of his

for we are told that Adam and Eve had daughters as well as sons.

(24) From there on, everything makes good sense if one

accepts the record as it stands.

One further point only remains

to be underscored. This is the perfectly proper absence (if all

that we have said thus far is true) of

24. 0ne further scriptural

reference may be mentioned. In Acts 17:26 we are told that God

derived all nations that dwell on the face of the earth

"from one." In the usual Authorized version rendering

the verse reads, "of one blood," but the best manuscripts

do not have the word blood. This could therefore be taken

to mean in the most literal sense that all nations have had their

ultimate origins, not merely in Adam and Eve, but even more specifically

-- since Eve was taken out of Adam -- in one man, Adam. This

would leave even less room for any multiple-origins theory. I

was interested to find this view reflected in the Jesuit commentator

Henricus-Rencken's book, Israel's Concept of the Beginning,

Herder and Herder, New York, 1964, p.225.

pg.14

of 16 pg.14

of 16

the

slightest indication that Cain was contravening any existing

prohibition against a brother-sister marriage. His action in

destroying his brother is condemned in no uncertain terms, but

there is no reference whatever to the existence of any prohibition

against incest as appears several thousands of years later in

the Book of Leviticus. This not only suggests that the prohibition

did not exist, not at that time being required, but that the

writer who recorded the events of Cain's life lived at a time

when brother-sister marriages were still not viewed as sinful

at all.

This absence of any condemnatory

note, in a record which elsewhere judges its "heroes"

in no uncertain terms when they contravene the laws of God, can

only be reasonably accounted for on the grounds that this record

as we have it is a contemporary or near-contemporary one and

not something concocted by a self-righteous priestly community

living some thousands of years after the event. Had they been

members of such a hierarchy and had they been knowledgeable enough

to realize that the prohibition was not necessary in Cain's time,

one might reasonably expect they would have added in parenthesis

at the appropriate place in the record some little note to the

effect that "at that time there were no laws against incest."

As the record stands, one gets the feeling that the writer was

totally unaware of any potential hazard in brother-sister marriage.

Conclusion

In

conclusion, it seems to me that the circumstances surrounding

the identity of Cain's wife have a significance in the light

of Christian faith for the following reasons. First, we know

from modern genetics why incestuous relations are most likely

to be damaging to the offspring. But we also know that by chance

such relations may not be damaging, a fact which demonstrates

clearly that under certain circumstances brother-sister marriage

might be not merely acceptable but greatly to be preferred from

certain points of view.

Second, our present understanding

of the processes of mutation, whereby the gene make-up of two

proposed marriage partners has become damaged, also allows us

to extrapolate backward into the past and say, with some measure

of assurance, that the further back we go, the less likely are

the offspring to suffer the consequences of inbreeding.

Third, the Bible supplies us with

a piece of historic information -- namely, the account of the

Flood and how the world's population was reduced to eight souls

-- which provides a key to the sudden loss

pg.15

of 16 pg.15

of 16

of vitality

in terms of longevity which Scripture states immediately followed

the re-peopling of the world.

Fourth, the events recorded in

the first few chapters of Genesis indicate that inbreeding was

either comparatively harmless or was carried out with decreasing

frequency as the centuries rolled by from Adam to Noah. In the

case of Cain and his sister, both of whom were siblings in Adam

and Eve's family, the amount of genetic damage carried in the

genes must have been very small indeed. At least this is true

if we believe, as I do, that Adam and Eve themselves were created

perfect at first, with no damaged genes.

In short, the circumstances are

all of a piece. If we allow the record to speak for itself, and

if on the basis of this record we draw these quite reasonable

conclusions, there is a ring of truth which accords perfectly

with the assured findings of modern human genetics; and this

is illuminatingly illustrated from the subsequent history of,

not only single families, but whole tribes of both civilized

and primitive peoples, in both modern and more distant times.

pg.16

of 16 pg.16

of 16

Copyright © 1988 Evelyn White. All rights reserved

Previous Chapter Next Chapter

|