|

Part I Part II Part III Part IV Part V Part VI |

Part II: The Necessity of the Four Gospels

|

|

|

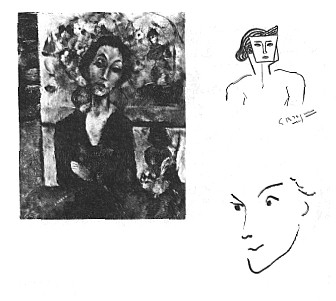

| Figure 2. Portraits of Maria

Lani by (above) Goerg; (top right) Braque; and (right) Matisse. |

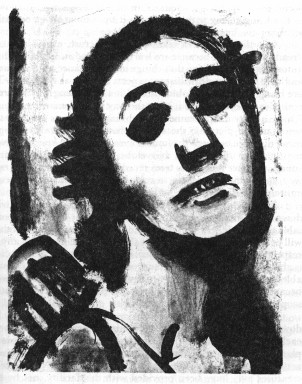

Figure 3. Portrait of Maria Lani

by Roualt. Courtesy of the Art Institute of Chicago |

The medium of expression so far has been graphic art. Does this still apply when portraiture is in words? Cassirer has this to say: (11)

No example is more characteristic and instructive in this respect than the change in our portrait of Socrates. We have the Socrates of Xenophon and Plato; we have a Stoic, a skeptic, a mystic, a rationalistic, and a romantic Socrates. They are entirely dissimilar. Nevertheless, they are not untrue, each of them gives us a new aspect, a characteristic perspective of the historical Socrates and his intellectual and moral physiognomy.

Plato saw in Socrates the great dialectician and the great ethical teacher; Montaigne saw in him the anti-dogmatic philosopher who confessed his ignorance; Friedrich Schlegel and the Romantic thinkers laid the emphasis upon the Socratic irony.

And in Plato himself we can trace the same development. We have a mystic Plato, the Plato of neo-Platonism; a Christian Plato, the Plato of Augustine and of Marsillio Ficino; a rationalistic Plato, the Plato of Moses Mendelssohn; and a few decades ago we were offered a Kantian Plato.

We may smile at all these different interpretations, yet they not only have a negative but also a positive side. They have all in their measure contributed to an understanding and to a systematic evaluation of Plato's work. Each has insisted on a certain aspect which is contained in his work but which could only be made manifest by a complicated process of thought. When speaking of Plato in his Critique of Pure Reason, Kant indicated this fact: "...it is by no means unusual," he said, "upon comparing the thoughts which an author has expressed in regard to his subject...to find that we understand him better than he understood himself."

11. Cassirer, Ernst, ref. 10, p.180.

In

short, we have a better understanding--I think it is safer to

say a more complete understanding--of the Lord by reason of the

four Gospels than we would have had if some super author had

left us with only one Gospel combining the substance of the others.

And I think it is remarkable how frequently it happens that to

make the composite picture complete, four portraits, not less

and not more, seem best suited. It is as though three portraits

provide us with a three-dimensional picture in space and

one more is required to complete the picture in time. In the

present case the three Synoptic Gospels seem clearly to be within

the single framework of space, while the fourth seems to add

the time dimension--opening with the words, "In the beginning...."

There is one other point of view

from which we may approach this subject, and it involves us in

a brief consideration of the nature of stereoscopic vision. Stereoscopic

sight involves the use of two eyes spaced a sufficient distance

apart that views are obtained from two slightly different angles

of vision. The mind in some mysterious way combines these two

views, different as they are, into a single picture that has

depth. Stereoscopic vision thus allows us to perceive the relative

distance of objects from us regardless of their size. We can

manage after some time of training to estimate these distances

with only one eye. We do this by a very rapid assessment of the

relative size of the objects which naturally appear to be smaller

as they recede into the distance. We learn to gauge distance

because of size. For every object, the mind somehow preserves

a kind of standard reference dimension. Two eyes make this particular

form of mental exercise unnecessary, and our gauge of distance

becomes much more

accurate � exceedingly

accurate, in fact, at close range. It allows us to touch something

without missing it by coming short, or without stubbing our finger

by over-estimation

An ordinary camera takes only one

picture, and it is flat. We "read" it in depth because

we learn so to read it. Children do not automatically recognize

that things in the distance appear smaller, and they therefore

draw distant objects as large as near ones. They are being more

truthful, but we find it a disturbing way to present reality

to the eye because it is not the way we customarily perceive

it. I have a stereoscopic camera which has two lenses and takes

two simultaneous pictures, the spacing between the lenses being

the mean distance between the human eyes (65mm). A special viewer

is required, but the effect is marvelous. One sees everything

in the round, whether it be a few trees receding into the distance

or even a fly trapped by the camera in midair. The fly hangs

in space. An entirely new dimension is added to the photograph.

A simple experiment can be performed

by anyone who will sit down in his living room and sight across

a chair or an object on the table to the wall behind it. By closing

one eye and then the other, it will be seen that the nearer object

shifts its position specifically with respect to some more distant

object in line with it. Each eye therefore is giving a slightly

different picture of the same scene, and the mind is able to

integrate them into a single view which has depth. However, because

our eyes are set in a horizontal plane, we have this stereoscopic

vision only in a horizontal plane and not in a vertical one.

We can obtain stereoscopic vision

in the vertical plane by lying down on a couch so that the eyes

are in the vertical with respect to each other. But now we lose

stereoscopic vision in the horizontal plane. Thus, to obtain

vision in depth in every direction we would actually have to

have four eyes. I think that in Nature certain creatures may

have been provided with this facility, not by being given four

eyes, but by being given the habit of bobbing the head up and

down very rapidly every so often. If we assume that their central

nervous system is designed to accept this sudden shift in the

vertical direction, stereoscopic vision might be achieved both

horizontally and vertically. Birds that live and feed in shallow

water while standing much of the time out of the water must be

able to compensate, when they strike for food in the water, for

the refractive index: and it is possible that they are able to

correct for this by the rapid bobbing up and down of the head.

I have no research evidence for this, but discussion with some

ornithologist friends indicates that it is a very real possibility.

Virtually

everyone has had the experience of watching a dog intently putting

his head first on one side and then on the other. The movement

is a rather delightful one. It seems to me that it, too, may

serve to enhance the dog's total perceptive capabilities in depth,

because it increases its range of stereoscopic vision above the

mere horizontal plane to which most animals are normally limited.

At any rate, whatever may or may

not be valid in the above observations regarding animal vision,

it is certain that to obtain 100 percent perception in depth,

we would have to have four eyes and a mind designed to unify

the four points of view. Both are required, for otherwise we

should be in effect imposing photographs shot from different

angles upon each other and trying to obtain a single print from

the composite. The result would undoubtedly be a blurred image.

There are some diseases known to man in which even the images

from the two eyes we have are not fused, and a conflicting double

image has to be eliminated by preventing the light from entering

one eye � or in a few cases by a mental process which is

learned and by which one picture of the two is somehow ignored.

Only special circumstances enable us to create a harmonious picture

out of "conflicting" material. The process is in the

mind.

Reverting to our consideration

of the four Gospels, it is only due to special circumstances

that we are able to create a harmonious picture out of apparently

conflicting records. The process here is a spiritual one. Just

as God has designed our minds to accept the conflicting evidence

of our two eyes that we might gain more complete vision, so God

has designed our spirits that we may somehow accept the conflicting

evidence of the four Gospels so that we might gain more nearly

perfect understanding. Just as the visual input to the mind is

perfectly integrated without our being aware of any conflict,

so do we for the most part read the four Gospel accounts without

being aware that they are in conflict. And finally, just

as by upsetting our vision we can make ourselves aware of the

divergence of the two pictures received by the eyes, so we can

if we wish become aware of the conflicts between the Gospel accounts.

In physical health we are not aware of any conflict between the

eyes, nor in spiritual health are we disturbed by any conflict

between the Gospels. By a virtually unconscious process we "integrate"

and gain in depth of vision. Years ago, Principal Cairns wrote,

with true eloquence, (12)

12. Cairns, Rev. Principal. "Christ the Central Evidence of Christianity," Tract No. 3 Present Day Tracts, Vol.1, Religious Tract Soc., London, 1883, p.9.

In the narratives of the Evangelists, the impossible is achieved. The living Christ walks forth and men bow before Him. Heaven and earth unite all through: power with gentleness, solitary greatness with familiar intimacy, ineffable purity with forgiving pity, unshakable will with unfathomable sorrow. There is no effort in these writers, but the character rises till it is complete. It is thus not only truer than fiction or abstraction, but truer than all other history, carrying through utterly unimaginable scenes the stamp of simplicity and sincerity, creating what was to live forever, but only as it had lived already; and reflecting a glory that had come so near and been beheld so intently, that the record of it was not only "full of grace," but of "truth."

Subsequently

the same writer concludes by saying, (13) "The difficulties of the Gospels from divergence

are as nothing compared with the impression made by them all

of one transcendent creation; and for my part, if I rejected

inspiration, I should have reason to be still more astonished...The

very diversities so often appealed to as an objection to this

conclusion really strengthen it and prove that writings which

can so bring forth the one out of the manifold have in them not

only truth but inspiration."

I cannot leave this aspect of the

subject without one further observation. In the previous chapter

we underscored the difference between what a man actually says

and what a man really means. In drawing a portrait with brush

or pen, it is equally important to distinguish between what a

man looks like and what he really is. Those who have had occasion

to do portraiture will know that if the subject is prepared to

pose for long enough, the superficial facial mask tends to relax

unconsciously and one slowly finds oneself drawing or painting

the real character rather than the superficial one.

I had occasion to draw a well-known

businessman. The drawing was to be a presentation to him by the

family. I had sufficient time with him to be able to draw him

as he was inwardly: and standing out from the page, rather surprisingly,

was a somewhat different and less pleasant character than the

man whom one saw in a casual encounter. Several persons who had

little or no respect for his integrity as a businessman, said

in effect, "Hmmm...that's him all right." He was not,

to those who knew him well, a pleasant man to have to deal with

in business. I hardly need to say that his relatives turned the

picture down. So I ended up in possession of one of the best

portraits I have drawn, technically speaking--and one of the

most worthless! I still have it...

13. Ibid., p.11.

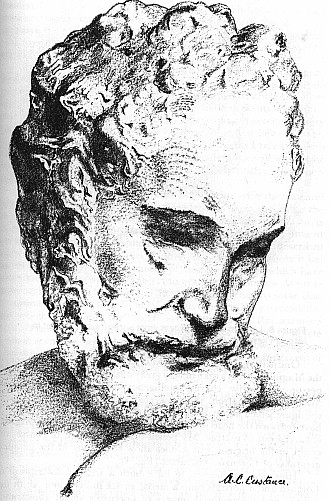

One of the greatest

figures of Michaelangelo's time was Lorenzo the Magnificent.

As a man of very great wealth, a patron of the arts, a person

of integrity, charm, intelligence, and wisdom, he became Michelangelo's

patron. When Lorenzo died, Michelangelo carved the figure which

adorned his tomb in the Medici Chapel in Rome. I have redrawn

the head of this reclining figure, which in the original is carved

out of marble. My pencil drawing cannot, of course, do credit

to the original, but it does show something of the genuine greatness

of Lorenzo's character (Fig. 4).

However, we happen to have both

a written description of Lorenzo and a portrait from a medal

struck in his honor. Both the written and the pictorial images

of Lorenzo's visual appearance agree in this, that he struck

the eye as rather a mean character with little manifest greatness,

with no physical presence that was immediately

impressive, with

a slight deformity in his back, and with a nose and mouth that

gave him a rather "untrustworthy" look. I have

redrawn the medallion, and it requires some stretch of the imagination

to equate it with Michelangelo's beautiful tribute to his benefactor

(Fig. 5).

Which is the true portrait: the

one which portrays how Lorenzo looked, or the one which portrayed

what he was? Michelangelo preferred the latter and although his

portrait contradicts the other one, they are both true portraits,

but from different points of view. To give the complete picture

of reality, it is necessary to perceive reality in different

ways so that what may appear to be two different statements of

the truth may really only be one. It seems likely that with our

minds constituted as they are, contradictions will always be

essential to the perception of truth, particularly truth about

a person.

There is a tremendous difference

between knowing the facts and perceiving the truth. Contradictory

evidence is likely to confuse the man who seeks only to know

the facts, but contradictory statement is often the only way

in which truth may be represented. In our present state of knowledge

it is customary to say that light is to be described both as

corpuscles and waves. Under certain circumstances it behaves

as though it were composed of discrete particles which have some

kind of mass and are subject to gravitational forces. At other

times its behavior is best explained by viewing it as having

some kind of nonmaterial wave form. The two views are seemingly

irreconcilable, which means that the "facts" are contradictory.

But scientists have learned to live with this contradiction,

since the most complete picture seems to depend upon both contradictory

views being accepted at the same time. Even in science therefore,

the statement of the truth may demand the use of contradictory

terms.

One of the wonders

of the Gospel story is that so few people in reading the four

Gospels year after year ever become aware of the "contradictions"

which are to be found between them. The fact is that we have

been given spiritual vision that enables us to see a single picture

of the Lord which, although it is presented from four different

points of view, reaches us without disharmony. The skeptic is

like the man with faulty vision whose mind cannot resolve these

four views except by a very deliberate effort and even then only

by some artifice. The Christian, on the other hand, can by an

equally deliberate process--as though he were closing one eye

at a time--separate out these different pictures and study them

profitably in isolation without at the same time destroying his

power to see the unified whole.

Of such a nature are

these four gospels that, as Rousseau said, the inventor of such

a Character as they present would be even more astonishing than

the Character Himself. It is undoubtedly true.

The portrait of the Lord Jesus

which emerges from the combined impact of the four Gospels demonstrates

indeed that fact is more amazing than fiction, that creative

imagination is no match for inspired record of truth. Here truly

is an uncreatable figure. Albertus Pieters, in his wonderful

little book, Divine Lord and Saviour, has a quotation

from the work of Carnegie Simpson which captures something of

the sheer beauty and splendour of the Saviour. (14)

They [the Gospels] do not merely affirm His stainlessness, which were easy. They exhibit it, which it were simply impossible to do except from the life. We have there what Jesus said and did in all kinds of circumstances and on all manner of occasions--in public and private, in the sunshine of success and the gloom of failure, in the houses of His friends and in face of His foes, in life and in the last great trial of death. It is the detailed picture of a man who never made a false step, never said the word that ought not to have been said, never, in short, fell below perfection. Such a portrait is of necessity a true portrait. It simply can not be an idealized picture. That which is so above; human criticism is not less above our conception....Only one thing accounts for their being able to do it. That is simply veracity. They had a model, and they copied it faithfully. And because, first, the model was faultless, the reproduction, being faithful, was perfect too.

14. Pieters, Albert, Divine Lord and Saviour, Revell, New York, 1949, p.96.

|

|