|

Abstract

Table of Contents

Part I

Part II

Part III

Part IV

Part V

Part VI

|

Part V: The Genealogies of the Bible

Chapter 2

The Genealogies of the New Testament

WE COME TO the

genealogies of the New Testament. Most wonderful and most illuminating

are these genealogies which establish the relationship of the

Lord Jesus to the rest of the human family. It is no new discovery

that each of the four Gospels appears to have been written and

directed by the Holy Spirit with a particular type of audience

in view. Matthew wrote for the Jewish people, presenting Jesus

Christ as the Hope of Israel. Mark wrote for the common man,

and in those days the common man meant virtually the slave, for

the Roman Empire was a world in which a comparatively few were

served by the vast majority, and that vast majority had little

if any personal dignity. Mark presented the Lord as the Servant

of Man par excellence. Luke wrote for the better-educated Gentile,

for whom the great goal was to be "the cultured man"

� or in Greek terms, one whose disposition was characterized

by the dual hallmark of a gentleman: "sweet reasonableness

and appropriate seriousness." Luke therefore presented the

Lord as the ideal man, the very Son of Man. These three, the

so-called Synoptic Gospels, set their sights at the same level,

playing between them a beautiful harmony of chords by taking

care to note, with inspired wisdom, those things which Jesus

said and did in his character as man � though never failing

to acknowledge his divinity. And finally, John built upon this

concordant testimony to the perfection of the manhood of Jesus

to show that part of the mystery of this perfection lay in the

fact that He was not merely the Son of Man but also the Son of

God.

Each of these authors, if one may

allow some liberty in the use of language, accompanied his record

with an appropriate genealogy. In Matthew the line of Jesus Christ

is traced forward from Abraham, the father of the Jewish nation.

In Luke the line is traced back to Adam, as the father of the

human race. In John the line

pg

1 of 18 pg

1 of 18

is traced back into eternity

with God. And what of Mark? How fitting that there should be

no genealogy here: who cared whence his servant came? Slaves

are not recorded, for records of this kind are kept only to establish

rights. And so it is only in a manner of speaking that each of

the Gospels has its appropriate form of genealogy, but the absence

of a genealogy in Mark is a beautiful tribute to the underlying

unity of Scripture and the perfect agreement between its parts.

Sometimes this perfect agreement

appears to be marred by contradiction, but I think it is an invariable

rule that the apparent contradictions challenge us to resolve

them and, in so doing, allow us to discover great truths which

would not otherwise be discovered, but which are like a feast

of fat things to the soul. This is never more true than in the

case of the seeming inconsistencies between the genealogies given

by Matthew and by Luke.

The easiest thing here is to assume either that one of them is

wrong, or that both of them are. Needless to say, a great many

writers who have casual respect for the Word of God have concluded

just this. To quote one such writer: (23)

There can be no doubt that the

anticipation that Christ would be descended from David was very

general in our Lord's time (John 7:42, etc.). It is also clear

that it was believed -- at least by the disciples -- that Jesus

was indeed descended from him (Matthew 1:1; Acts 2:30; 12:23;

Romans 1:3; Revelation 22:16, etc.). The genealogies in Matthew

and Luke are apparently inserted to prove that this is a fact.

But at first sight it would appear that the two genealogies are

mutually destructive and that one or both are entirely untrustworthy.

They both appear to be genealogies of Joseph, but they start

from two different sons of David, and they end with the discrepancy,

which cannot be ascribed to a copyist's error, in the name of

Joseph's father.

These genealogies

are provided as an insert, since it is important to have the

text; human nature being what it is, there may be a tendency

for the reader not to take time (even if he does get out a Bible)

to check back and forth from the one to the other as we study

the two family trees.

With this text before us, let us

consider certain segments of these two genealogies under four

headings:

1. Anomalies that appear within a genealogy

itself;

2. Apparent conflicts with background information in the Old

Testament;

3. Contradictions between the two genealogies;

23. Crewdson, G., communication in Transactiions

of the Victoria Institute, vol. 44, 1912, p.26.

pg.2

of 18 pg.2

of 18

4. Departures from

the normal method of setting forth this kind of information in

public records of

this kind.

Section 1: Anomalies That Appear

Within a Genealogy Itself

The number of names listed in Matthew's genealogy

presents a problem, for we are informed that they total three

times fourteen, or 42 in all (Matthew 1:17); but if we count

them, there appear to be only 41. It is clear enough that there

are 14 names from Abraham to David, and 14 names from Solomon

to Jechonias, but unless we repeat Jechonias we have only 13

names for the balance. The only justification for repeating Jechonias

is to make the assumption that this one name stands for two separate

individuals whose original names may in their Hebrew form have

been slightly different, but whose Hellenized transliteration

has assumed the same form. Genealogical records provided elsewhere

in Scripture supply us in a rather remarkable way with information

demonstrating that this assumption is probably correct.

To begin with, it will be noted

in Matthew 1:11 that the first-mentioned Jechonias is said to

have been accompanied by "his brethren". If this Jechonias

is identified with Jehoiakim, he is in fact the immediate son

of Josias, as Matthew tells us, and did indeed have brothers,

as 1 Chronicles 3:15 informs us -- namely, Johanan, Zedekiah,

and Shallum.

This man Jehoiakim, in turn, had

a son Jeconiah (I Chronicles 3:16), but this son did not have

"brethren": he had only a single brother -- whose name

happens also to have been Zedekiah (I Chronicles 3:16). Undoubtedly

Jeconiah is to be identified with the Jechonias of Matthew 1:12,

who became, as I Chronicles 3:17 assures us, the father of Salathiel

(of Matthew 1:12).

In other words, the first Jechonias

of Matthew's genealogy is to be identified with the Jehoiakim

who had three brothers. The second Jechonias of Matthew is to

be identified with the Jeconiah who had only one brother and

who went into captivity into Babylon and who there raised a son,

Salathiel.

All this makes perfectly good sense

and restores the proper number of names to complete the tally

of three times fourteen, provided that one understands that the

two entries of the name "Jechonias" in Matthew do not

represent one individual but two. The first is distinguished

by having several brothers; the second bore Salathiel in captivity.

pg.3

of 18 pg.3

of 18

Not

a few commentators who have little confidence in the Word

of God have, in the past, taken the apparent

discrepancy in the total count of generations -- along with the

fact that Matthew omits a certain number of names (as we shall

see in the following section) -- as a proof that Scripture is

far from being historically accurate or consistent. The mathematical

inconsistency here in Matthew's genealogy is apparent only and

results from paying insufficient attention to the precise wording.

This inattention is inevitable if one has only a low regard for

the Word of God. But if we observe that the first Jechonias is

said to have had brothers and the second Jechonias had only one

brother, then the difference between the two is clear to the

attentive eye. Indeed, what better assurance could God have supplied

us as a means of identification and distinction, especially if

He foresaw that the names which are so distinct in their Hebrew

form should in due time become confused in the Greek?

Section 2: Apparent Conflicts Within

Old Testament Background Information

By contrast

with a fair proportion of Luke's genealogy, Matthew's genealogy

is clearly derived from records which are still accessible to

us from the Old Testament. Many of the names in Luke are not

to be found there. This enables us to go back to the originals,

as it were, and when we do this, we may be surprised to find

that Matthew has omitted quite a number of names which by normal

standards of keeping such records ought to have been included.

The circumstance demonstrates rather clearly that Matthew's genealogy

has a special character to it.

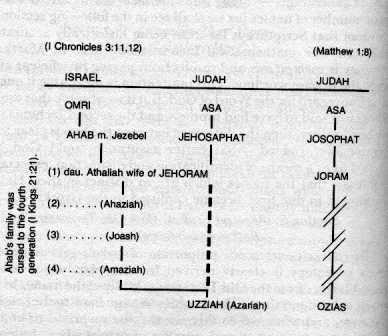

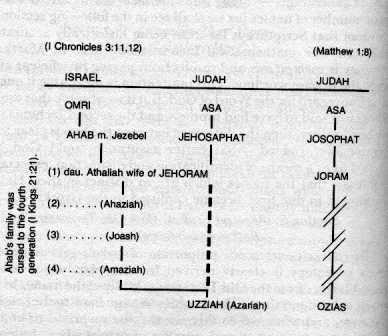

Here we meet with a beautiful illustration

of what is God's view of history as opposed to man's. While Matthew

1:8 counts Ozias (Uzziah in the Old Testament) as the son of

Joram (Jehoram in the Old Testament),

1 Chronicles 3:11,12 shows that in actual fact he was not his

son but his great-great grandson.

When Jehoram came to the throne

of Judah, Israel to the north was being led more and more deeply

into wickedness by their worst king, Ahab, and his notorious

queen, Jezebel. Jehoram shows the set of his sail by marrying

their daughter, Athaliah. The history of the royal house of Judah

then passes into one of its saddest phases: the immediate descendants

of Athaliah and Jehoram became involved in a series of disastrous

events which dreadfully fulfilled the judgment of God pronounced

through Elijah (I Kings 21) against the line of Ahab and Jezebel,

a judgment which persisted "unto the third and fourth generation".

pg.4

of 18 pg.4

of 18

When Jehoram died of some atrocious

disease, as Elijah had warned him he would, his son (Ahaziah)

came to the throne. Having aapparently learned absolutely nothing

from the judgment which had befallen his father, Ahaziah proved

himself an equally wicked monarch and was murdered in a popular

uprising. His mother, Athaliah (Ahab's daughter, it will be remembered),

perhaps in a fit of fury and remembering Elijah's judgment against

her house, executed judgment herself upon it and set out to murder

every remaining male of her father Ahab's line. But it happened

that Ahaziah's youngest son, Joash, had a sister who was endeared

to him; this sister managed to spirit him away and hide him,

so that in due time he was unexpectedly brought out of hiding

and, at the age of seven, presented to the people as their rightful

king.

Joash appears to have been a better

man than his father or his grandfather. But whether by his very

nature, or because the priesthood which should have aided and

guided him was itself equally corrupt, he too failed to improve

the spiritual life of the people he ruled. In due time Joash

also became a prey to treachery, being murdered by his own servants

while he was in bed.

Joash was succeeded by his son

Amaziah who, unlike his father, seems to have tried to do the

right thing but, as Scripture says, "not with a perfect

heart". After various intrigues and a fatal engagement with

Israel,

pg.5

of 18 pg.5

of 18

Amaziah departed entirely

from the vision he once had and ended up a defeated man and a

fugitive. Escaping from Jerusalem when he learned of a conspiracy

against his life, he fled to Lachish. But they pursued him there,

and there he too was murdered.

Amaziah was succeeded by his son

Uzziah, the "Ozias" whom Matthew in his genealogy sets

forth as the son of Joram. In other words, three generations

are missing, three generations of kings of Judah who, while they

preserved intact the line of the Promised Seed, did not in themselves

prove worthy to be remembered in it. Thus the curse pronounced

upon the house of Ahab by Elijah, God's mouthpiece, persisted

unto the fourth generation: Athaliah was the first generation

of Ahab's line, Ahaziah was the second generation, Joash the

third, and Amaziah the fourth. In the official temple records,

it may be that the names of Ahaziah, Joash, and Amaziah were

removed or marked in some way as having no official status in

the royal line -- just as in Europe a Bar-Sinister may be marked

across the arms of a dishonoured branch of a family.

Evidently, at that period in history

and for many centuries after, there was observed the practice

of removing from all official records the names of individuals

who had brought shame upon themselves. The Athenians, according

to Livy, pronounced a similar doom on the memory of Alcibiades,

and of Philip V of Macedon in the year 200 B.C. (24) In Egypt during the time

of the eighteenth dynasty, the Egyptian priests similarly cursed

the memory of Amenhotep IV and sought to remove his name from

all monuments. The same thing was done with the name of Hatshepsut

by her successors.

It is a curious thing how potent

is the threat to the individual of having his very remembrance

blotted out. It was called, in the days of Imperial Rome, the

Damnatio Memoriae, and it was carried out in a striking

manner against the emperor Commodus. (25) His "memory was condemned" in a single

night's sitting of the Senate within twenty-four hours of his

death, the same night in which Pertinax was nominated as emperor.

It was decreed that every statue of Commodus was to be destroyed

and his name erased from every private document and public monument.

One wonders what they did with his name on the document which

ordered its removal!

24. Livy, Book XXXI, Chap. 44: as quoted

by A. S. Lewis, "The Genealogies of Our Lord," Transactions

of the Victoria Institute, vol. 44, 19I2, p.12.

25. Lucius Aurelius Commodus was surely the most degraded

and utterly corrupt of all Roman emperors. His short history

is disgusting, and it is some credit to the Romans that after

his murder in A.D. 192, the Senate attempted to blot out his

very memory.

pg.6

of 18 pg.6

of 18

It

seems a reflection of something we find not infrequently in the

Old Testament and even in the New. God had warned Israel "whoso

sinneth against Me, him will I blot out of my book" (Exodus

32:33). The same thought is reflected in Deuteronomy 9:14; 25:19;

29:20; and in 2 Kings 14:27. In Psalm 9:5 we read, "Thou

hast rebuked the nations, Thou hast destroyed the wicked, Thou

hast blotted out their name forever and ever." This is repeated

in Psalm 69:28: "Let them be blotted out of the Book of

Life." By contrast is the promise to the redeemed in Revelation

3:5, "I will in no wise blot out his name from the Book

of Life." So in effect, when God assures David that He will

blot out his sins and remember them no more, He is saying that

they shall be as though they had never been. And in the genealogy

which leads from Abraham to Christ, these three men -- Ahaziah,

Joash, and Amaziah -- are blotted out as though they had never

been and it seems therefore that if this erasure of their names

took place in the original official documents which had been

preserved in the temple from time immemorial, Matthew may have

merely copied down precisely what he found in the record.

Some authorities wonder where either

Matthew or Luke obtained his genealogy, since they believe that

all such records were lost in the destruction of the first temple.

However, it is generally agreed that a knowledge of one's genealogy

was of very great importance in every Jewish family even when

they went into exile, because it was only on the basis of this

information that the Promised Land could be divided justly. With

the ready means that we today have available for keeping written

records, our faculty for remembering may have suffered in some

respects. But where written record is more difficult to secure,

prodigious feats of memory are not infrequently observed. Native

people have been reported by missionaries to have memorized whole

books of the New Testament, apparently without too much difficulty.

And it is well-known that the Arab youth was formerly -- and

perhaps still is -- expected to be able to recite his own genealogy

for seventy generations. When an Australian aborigine comes unexpectedly

upon another family's camp, he sits down some distance away from

it until an elder from the camp comes out to him. Thereupon the

two will recite their genealogies until they strike a common

ancestor, and when this has been done, the stranger will be invited

in and introduced with the proper identification as to his relationship,

so that everybody else in the camp will know how to address him

correctly, and he them.

Josephus speaks of the great care

which the Jewish people in his day took to preserve certain lines,

pg.7

of 18 pg.7

of 18

in particular the royal

line from David and the royal priesthood. Julius African (26) says that Herod the Great

caused as many official registers as he could get hold of to

be burned, because he himself was of a plebeian family and he

wanted to conceal from the Roman emperor the fact that he had

no blood relationship with either the royal line of David or

the priestly line of Levi. But it seems unlikely that he could

destroy them all, and the existence of private family registers

is proved by the discovery of Aramaic documents concerning the

Jewish colony which existed between 471 and 411 B.C. at Elephantine

near Assoun. This is, of course, much earlier than Herod, but

it shows that some genealogical information survived outside

of Palestine even if Herod was fairly successful locally. According

to a fairly recent Jewish Encyclopedia, (27) we are told that in the Talmudic Age -- i.e., subsequent

to Herod's time -- interest in preservation of genealogies was

lessened, but the patriarchs in Palestine and the exiled patriarchs

in Babylon down to the thirteenth century kept these records

alive wherever possible, and the former were believed to possess,

interestingly enough, unbroken descent from David in the male

line only. This is a point of some interest in view of the fact

that Luke's genealogy is widely considered to be that of Mary.

By the omission of these three

names, we have an illustration of a point made much of by those

who wish to extend the chronology of the Bible sufficiently to

accommodate current views of the antiquity of man which demand

anywhere from 200,000 to 500,000 years. The claim is that these

genealogies do not supply us with an unbroken series of generations

because there are known gaps, such as that in Matthew 1:8, which

makes a great-great-grandson a son, thus skipping three generations.

What is never admitted by those

who attempt thus to extend the biblical chronology is that the

possibility of arguing for such gaps exists only because elsewhere

in Scripture the gaps are filled in. Had we only a single genealogy

for example (for some particular period), we would have no evidence

that gaps existed in it. It is only when the same period is supplied

elsewhere with genealogical material (which neither provides

us with more generations for the same period, or with fewer generations

for the same period) that we can say with any certainty that

a genealogy may be presented which is not actually complete though

it has the appearance in itself of being so. It is perfectly

true that when we are told that such-and-such a man is the "son"

of some other individual, we are not always to assume that it

means sonship in our more limited sense, since Ozias was the

26. Africanus: quoted by Eusebius, History

of the Church, 1,7.

27. "Genealogy," in Standard Jewish Encyclopedia,

Doubleday, New York, 1962.

pg.8

of 18 pg.8

of 18

son of Jehoram only in

the sense of being a descendant.

But this surely does not allow

us to assume that, wherever we decide it would be convenient,

we are free to insert an unlimited number of generations merely

because the word son has this wider meaning. The fact is that

in the historical portions of Scripture -- that is, in those

parts of the Bible which detail the lives and doings of individuals

-- we can find no break anywhere in the record in the historical

account itself. People's doings are set forth relatedly so that

one gets the feeling -- which undoubtedly results from the fact

that this is a continuous record -- that each succeeding generation

picked up the historical threads of those who immediately preceded

them and united the past and the future by their own doings.

This is manifestly true even in the very earliest parts of Scripture

which record the growth of civilization before the Flood as well

as its recovery immediately after it. Moreover, as we have seen,

there are chronological cross-ties in the record wherever the

line from the first Adam to the Last Adam is being traced. The

omission of these three names from Matthew's genealogy does not

give us permission to take liberties with the genealogies, but

only teaches us that God discounts entirely and blots out of

history whatever has come under his judgment. This is an unhappy

thing for those who have not experienced redemption, but it is

wonderfully reassuring to those who have, since by his gracious

action in so doing, the redeemed can have nothing to fear in

the judgment, for there will be no record against them.

Another example of apparent conflict

appears in Matthew 1:7, which tells us that Solomon begat Rehoboam

who begat Abia who begat Asa. In I Kings 14:31 we are told that

when Rehoboam died, his son Abijam (to be identified with the

Greek form Abia of Matthew) reigned in his stead. In I

Kings 15:2 we are told that Abijam's mother's name was Maachah,

and that she was the daughter of Abishalom. In 2 Chronicles 11:20,21

this individual, Abishalom, is named alternatively as Absalom.

Jewish tradition identifies this Absalom as David's son - which

is quite possible, since David bore Absalom by a woman named

Maachah -- and this would account for Absalom's naming his daughter

after the mother. Now, in Matthew, Asa is said to have been Abia's

son with which I Kings 15:8 agrees -- for it says that when Abijam

died, his son Asa reigned in his stead. But the curious thing

is that the record in Kings goes on to say that he reigned for

forty-one years in Jerusalem after succeeding to the throne,

and "his mother's name was Maachah, the daughter

of Abishalom." Thus Asa who was the son

pg.9

of 18 pg.9

of 18

of Abia nevertheless

appears from the text to have had the same mother. It is conceivable,

of course, in a case of incest, but this is certainly not true

here, otherwise Matthew's genealogy would surely have omitted

one of the names at least, if not both -- for such a thing as

incest was an abomination in the sight of the Lord. The explanation

is undoubtedly that Maachah was indeed the mother of Abia and

the grandmother of Asa. Thus, while -- as we have already seen

-- a son or a grandson may look back to a common father, similarly

a son or a grandson may evidently look back to a common mother.

Indeed, in I Kings 15:8,11 Asa is said to have been the son of

both Abijab his father and the son of David, the latter being

more precisely his great-great-grandfather.

This is the simplest way to reconcile 2 Chronicles 13:2 with

I Kings 15:2. In 2 Chronicles 13:2 Abijah's mother's name is

also spelled "Michaiah", where she is given as the

daughter of Uriel of Gibeah. Therefore Absalom must have married

a girl from Gibeah named Uriel (even though the name Uriel is

otherwise used of men only), for in I Kings 15:2 Abijah is said

to have been the son of Maachah the daughter of Absalom.

pg.10

of 18 pg.10

of 18

Working

out these little problems not merely enlarges one's understanding

of the relationship of these peoples, but somehow makes the individuals

live, as a map makes places live that we have once visited. And

if it is not irreverent to say so, finding solutions is like

finding a missing piece in a jigsaw puzzle or a missing word

in a crossword puzzle -- it provides genuine intellectual satisfaction.

Section 3: Contradictions Between The Two Genealogies

Luke provides

us with a line from Adam to David, a section of the genealogy

which is not found in Matthew, for reasons already noted, and

which therefore in no way conflicts with it. But from David forward

to Jesus there are disagreements almost all the way along.

Needless to say, these disagreements

were once made much of by those who held a low opinion of the

integrity of Scripture. But in due time these very disagreements

led to a search for some means of reconciliation, and this search

proved fruitful because it brought to light a further truth which

might otherwise have escaped notice entirely. Now that the truth

is recognized, there seem to be many incidental confirmations

of it from other parts of Scripture; but these confirmations

were not recognized as such until the truth they confirmed had

itself been rediscovered.

This discovery is that Luke's genealogy

traces the line of Mary, not of Joseph. Thus, at the very beginning

of Luke's record -- a record which sets the names in the reverse

order from that given in Matthew -- we meet with the first "contradiction":

namely, that Joseph was the son of Heli, whereas Matthew says

that Joseph was the son of Jacob. Although some of the early

Church Fathers perceived that this was Mary's pedigree, they

did not apparently make the discovery that in the Talmud, Jewish

tradition held that Mary was the daughter of Heli (Beth-Heli).

(28) Early Christian

writers held that Mary was the daughter of Joiakim and Anna.

But the name Joiakim is interchangeable with Eliakim, as 2 Chronicles

36:4 shows, and Eli or Heli is an abridgment of Eliakim. It is

thus quite possible that the early Christian tradition is in

perfect harmony with that of the Jewish people themselves whose

knowledge would be based on temple records. This is undoubtedly

the basis of the early

28. Jerusalem Talmud, Haggigah,

Book 77,4.

pg.11

of 18 pg.11

of 18

assurance that Jesus

was, in the flesh, of the seed of David. In the annunciation

(Luke 1:32), the promised Saviour is called at once "Son

of God" and "Son of David": Son of God by virtue

of his conception by the Holy Spirit, and Son of David by virtue

of his birth through Mary. This should therefore be compared

with Romans 1:3,4, in which we are told that He who was God's

Son was "born of the seed of David according to the flesh

and declared to be the Son of God with power. . . . " Later

on, in his confrontation with the Jewish authorities, Jesus answered

a question which had probably arisen from the fact that, while

they recognized the validity of his lineal claim to being David's

son through Mary, they would not recognize his further claim

to being the Son of God. He pointed out to them from Psalm 110:1

that while the Messiah was indeed to be David's son, David nevertheless

called Him "Lord". They had no answer to this. The

Lord's argument could only have real force if the people to whom

it was addressed recognized his claim as the son of Mary who

was a daughter of David.

Why, then, is Mary's name not included in Luke's genealogy? Undoubtedly,

to establish a legal pedigree it is necessary to set down the

name of the head of the household -- in this case, of course,

Joseph. At the same time, according to the Jewish way of thinking

-- and indeed, according to the common practice of many other

societies -- the man who married could claim his wife's father

as his own. We ourselves recognize this right, only we make the

distinction of saying "father-in-law" -- rather than

"father". There are a number of examples in Scripture

where this principle is followed.

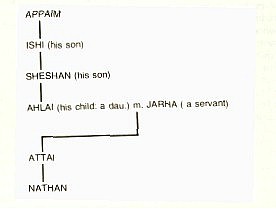

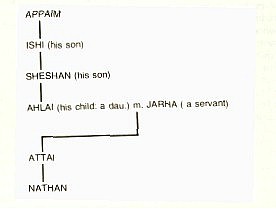

In I Chronicles 2:31 we have an

illustration of this practice of naming another as the father.

In this instance it will be observed that son succeeded "son"

until we come to Ahlai, whom we know had a daughter but not a

son. Meanwhile Ahlai had an Egyptian servant named Jarha and,

as was not altogether unusual at that time, he gave his daughter

to him as a wife. But from then on the children are still credited

to him as his descendants -- that is, members of his own line

through his daughter -- and therefore listed as his sons and

grandsons. Thus the children of his daughter are listed as his

children rather than the children of his daughter's husband,

and they in their turn would look back to him as their ultimate

father. Of necessity, Jarha would therefore be accounted as Sheshan's

son. The following genealogy sets this forth:

pg.12

of 18 pg.12

of 18

The manner in

which Joseph's name is introduced in Luke's genealogy is also

exceptional. Whereas each man in the line is said to have been,

simply, "of" his father, Jesus is said to have been

the son "nominally" of Joseph -- such is the Greek

which the Authorized Version renders "as was supposed".

The verbal root of this qualifying term is nomidzo, which

has the sense of legal standing or standing established by custom:

it is cognate with the root which gave rise to the English form

"nominal". Thus it was clearly recognized that Jesus

was the son of Joseph legally, but not necessarily by natural

generation. This claim is accepted without question in John 6:42,

"whose mother and father we know."

When a man wished to identify as

his son one who was not his son by natural generation, he could

do so by a process of legal adoption which involved two acts.

In the first place, he must name the child. Evidently the name

"Jesus" was registered as the child's name by Joseph

in obedience to the angel's instructions in Matthew 1:21. These

instructions, it will be noted, were given by the angel directly

to Joseph himself rather than to Mary. The significance of this

from the legal point of view is great. Although Joseph appears

to have predeceased Mary, it does not appear that anyone ever

seriously challenged his familial rights.

The second requirement has an interesting

history to it. It is well-known that the Code of Hammurabi played

an important part in structuring much of the social custom of

the Jewish people, since it was the legal

pg.13

of 18 pg.13

of 18

code in force at the

time of Abraham. In section 188 of this code it is written: "If

an artisan takes a son to sonship and teaches him his handicraft,

no one may bring a claim for him". Evidently Joseph taught

Jesus to be a carpenter in fulfillment of this recognized requirement,

a guarantee which would stand even if the records in the temple

were destroyed. It was a kind of double insurance of legal status.

A comparison of Matthew 13:55 with Mark 6:3 shows that both father

and son were carpenters. Matthew 11:30 tells us something of

his skill!

Thus, although Mary in her own right could claim descent from

David through Heli her father, the temple record could not enter

her name in the line but must enter the name of her husband,

the adopting father of her child. So when Luke copied out this

record, he quite properly omitted Mary's name and substituted

that of Joseph.

We have, therefore, a genealogy from David to Mary preserved,

presumably, in the family of Heli and perhaps actually in their

possession -- for as we have already noted previously; long after

the temple was destroyed with all its records, there still existed

families who claimed descent from David and claimed it, significantly,

in the female line. On this account the names in Luke's Gospel

from David forward do not coincide (except at one point) with

the names in Matthew's Gospel. David had three sons of note --

namely, Solomon, Absolon, and Nathan -- and it is in the line

of Nathan that Mary's claim is established.

In Luke 3:28 we have "Melchi";

in Luke 3:27 his son is given as "Neri"; and his son,

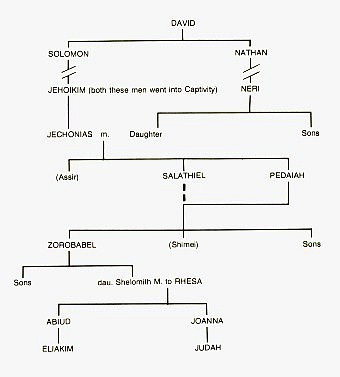

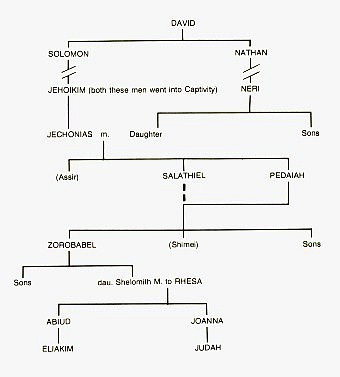

in turn, is given as Salathiel followed by Zorobabel and then

Rhesa. At this point we have some apparent connections with the

genealogy in Matthew's Gospel, for in Matthew 1:12 we have Jechonias

whose son was Salathiel followed by Zorobabel. When we turn to

the Old Testament to find out what this uniting of the two families

signifies, we find ourselves with insufficient information to

provide an unequivocal answer -- but just enough to allow a reconstruction

which, in the light of what we have already observed of the way

in which relationships are acknowledged, has a fair degree of

probability about it. The Jechonias of Matthew 1:12 was, as we

have seen, the king who terminated the Judean royal line when

these unfortunate people went into captivity. Although he is

stated to have been still a child, he survived long enough in

captivity to reach a marriageable age; he evidently was later

accorded kingly status -- a not unusual circumstance in those

days -- for the girl he married is called (in Jeremiah 29:2)

"his queen". Scripture has taken care to provide us

with very concrete information to this

pg.14

of 18 pg.14

of 18

effect (2 Kings 25:27-30)

as though God foresaw that one day this information would be

important.

Now, to bring the two genealogies

at this point into harmony, it is only necessary to assume that

Neri of Luke 3:27 also went into captivity and there raised both

sons and daughters, and that one of these daughters became the

wife and queen of Jechonias. This is a most reasonable assumption

really, because, if Neri was known to be of the royal line through

Nathan (and Nehemiah 7:5 shows that at least some genealogies

had been saved in spite of the conquest of Judah), then who would

be more proper as the wife of the still-acknowledged king than

a daughter of the royal line? Of this marriage, Jechonias had

a son (among others) whose name was Salathiel (I Chronicles 3:17)

and besides Salathiel he had also a second son named Pedaiah.

In I Chronicles 3:19 Pedaiah had a son named Zerubbabel (the

"Zorobabel" of the New Testament). Thus Salathiel was,

in fact, properly called the son of Jechonias but also the son

of Neri through the latter's daughter. The two lines from David

through Solomon and through Nathan meet in Salathiel by this

device. Salathiel's brother, Pedaiah, though not mentioned in

either of the New Testament genealogies, appears to have exercised

the right of the Levirate upon the early death of his brother

Salathiel, and to have taken his wife, by whom he raised up to

Salathiel's line a son named Zorobabel.

In Zorobabel we again meet with

an example of a man's children being traced through their mother's

father. Zorobabel had both sons and daughters, but the male seed

for some unknown reason came to an end, thus fulfilling the prophecy

made in Jeremiah 22:30 that no man of Jechonias' seed "should

sit on the throne of David". We are, however, given his

daughter's name in I Chronicles 3:19 as "Shelomith".

We have only to make one further assumption, namely, that this

girl married the Rhesa of Luke 3:17 and had of this union two

sons -- Abiud of Matthew 1:13 and Joanna of Luke 3:17 -- and

the rest makes perfectly good sense and the two genealogies are

reconciled, the one with the other.

By this means -- always bearing

in mind the manner of stating relationships which was allowable

-- we can see how, according to Matthew, Jechonias had a son

Salathiel and Salathiel had a son (via his brother Pedaiah) Zorobabel,

and Zorobabel a son (actually a grandchild through his daughter

Shelomith) named Abiud, and thence down to Joseph: and at the

same time, according to Luke, how Neri could have a son Salathiel

(actually his grandson), who had a son Zorobabel (again, in fact

a grandson), who had a son Rhesa (actually his

pg.15

of 18 pg.15

of 18

son-in-law, as Joseph was Heli's son-in-law),

and Rhesa a son, Joanna by his wife Shelomith who was a daughter

of Zorobabel, and thence down to Heli.

This sounds terribly complicated,

but the full genealogical table (see file Adam.html) which gives

both lines, will show that all the requirements of all that we

know, both from the Old and the New Testament, seem to be satisfied.

There are no conflicts either between

the Old and the New Testament records or between Matthew and

pg.16

of 18 pg.16

of 18

Luke. The validity of

the claim that Jesus was the promised Messiah as the Son of David,

the Seed of the Woman as virgin-born through Mary, the Saviour

of mankind as the Son of Man (from Adam) and the Son of God (as

conceived supernaturally by the Holy Spirit) is assured on every

ground.

Undoubtedly a study of the genealogies

requires considerable effort, perhaps more effort (or at least

a different kind of effort) from that which normally proves most

fruitful when expended elsewhere in Bible study. But it is well

worth it and brings with it a peculiar intellectual satisfaction.

Section

4: Departures From the Usual Way of Setting Forth a Genealogy

The fundamental departure found

in Luke's Gospel, is that in this genealogy we are not presented

at the top of the page with the oldest antecedent followed by

father, sons, grandsons, and so on, but rather with the latest

in the line, who is then by a simple device traced backwards

-- whereas all other genealogies trace forward. Why was this

order adopted?

There is a second departure, namely,

that whereas Matthew and John both commence their history

by establishing the pedigree, Luke covers briefly but effectively

a period of some thirty years in the life of the Lord before

saying who He is in terms of his antecedents.

It is not until this time -- when

Jesus, being now about thirty years of age, has been identified

by John as the "Lamb of God which taketh away the sin of

the world" and singularly considered by God in heaven as

His beloved Son in whom He is well pleased -- that Luke sets

forth his lineage, showing in effect that though the circumstances

of Jesus' birth were such as to set Him apart from all other

men, yet He was nevertheless truly representative of man in Adam.

The genealogy of Matthew reads

forward from Abraham to Jesus, identifying Him as the Child of

Promise. Promises are always of the future, and Matthew wished

above all to establish from the very first that Jesus was the

Christ, the fulfillment of this promise. He wanted to show the

grounds upon which Jesus established his title as the Messiah,

and his Gospel thereafter presents His credentials as the Son

of David.

Luke, on the other hand, wished

to show the potential of man, the model which God had in mind

from which all other men derive whatever of manhood they happen

to have. Hence he begins with Jesus and

pg.17

of 18 pg.17

of 18

appropriately gives

Him alone, above all others, the title "Son of Man",

and then he traces Him back to Adam, in whose place He stood.

Thus Matthew begins with Abraham and

leads us forward to the Lord, whom he identifies by his title,

"the Christ" (Matthew 1:17); whereas Luke begins with

the Lord, whom he identifies by his name, "Jesus"

(Luke 3:23), and leads us back to Adam and so to God.

Viewed as vehicles for conveying

information, the genealogies of the Bible are supportive of one

another. Were it not for the genealogical material in the Old

Testament, the genealogies in the New Testament would be without

historical foundation; and were it not for the genealogies in

the New Testament, the genealogical material of the Old, preserved

with such precision, would be without point. One set of data

looks forward, and one looks backward. Each is required to complete

the other. Just as we are learning, contrary to earlier expectations,

that there are no useless or vestigial organs in the body, so

we shall learn, perhaps contrary to present expectation, that

there are no useless entries in the Word of God. All Scripture

is given by inspiration and is profitable. . . .

(2 Tim. 3:16). The brief treatment of the genealogies in this

Paper barely scratches the surface of only a few of them. There

is yet much to be discovered, enough undoubtedly to keep a man

occupied for a lifetime.

pg.18

of 18 pg.18

of 18  Copyright © 1988 Evelyn White. All rights

reserved

Previous Chapter *

End of Part V * Next Chapter (Part VI)

Copyright © 1988 Evelyn White. All rights

reserved

Previous Chapter *

End of Part V * Next Chapter (Part VI)

|