|

Abstract

Table of Contents

Part I

Part II

Part III

Part IV

Part V

Part VI

Part VII

|

Part II: Primitive Cultures: The Problem

of Their Historical Origin

Chapter 2

Climax at the Beginning

THE PURPOSE

of this chapter is to establish two points. First, in that area

of the world from which all existing civilizations have derived

their inspiration and which might, therefore, properly be called

the Cultural Cradle of Mankind, the time lapse from the establishment

of the earliest human settlements to the building of the first

cities was remarkably short. Secondly, when new techniques and

arts and skills make their first appearance they are frequently

at the peak of their achievement and the course of their subsequent

development is one of decline, not evolution.

Let me elaborate these two points

somewhat. First, the rapidity with which civilization developed

after the Flood, for which there is archaeological evidence,

must have been paralleled by a similar rapidity of development

from Adam to Noah. During this earlier period although archaeological

evidence is still lacking, there were special circumstances which

account for the acceleration and these will be discussed in the

final chapter. My own impression is that when the Flood came,

mankind had not spread very far from the traditional "home"

of the race. With the destruction of all that preceded except

for those elements of that culture which were carried over the

Flood by Noah and his sons, a new start was made. But if an analogy

may be used, the new beginning did not represent the first faltering

paces of a child but rather the steps of an adult who has recently

emerged from an operation intended to remove a sickness which

could only have rendered further progress in civilization disastrous.

It is this circumstance which I believe accounts for the remarkably

rapid transition from Sialk and other Iranian Highland Plateau

settlements to the advanced cultures of Elam, the Indus Valley,

Mesopotamia Palestine, and Egypt.

Secondly, with respect to the evidence

for cultural degeneration it must first of all be admitted that

cultural progress does undoubtedly

pg

1 of 22 pg

1 of 22

take place. Within the

past 75 years, so many advances have been made in the means of

communication and travel, in medicine and in our control of the

environment in general, that it would be foolish to deny it.

Such advances have not all been gain, but fundamentally man's

heart, and not his head, has been the cause of this. But we have

been so bombarded with the concept of evolutionary progress that

the reverse process has been almost overlooked. Hence in the

chapters which follow the emphasis is upon degeneration, not

because we wish to deny a general trend in the opposite direction,

but rather because such emphasis is necessary to produce a balanced

view of history. The almost complete occupation by earlier Christian

scholars with the evidence for degeneration led to a reaction

which prepared the way for an evolutionary philosophy, which

was accepted not merely with openness but with relief and unbounded

optimism. Perhaps it is time to take a fresh look at the situation.

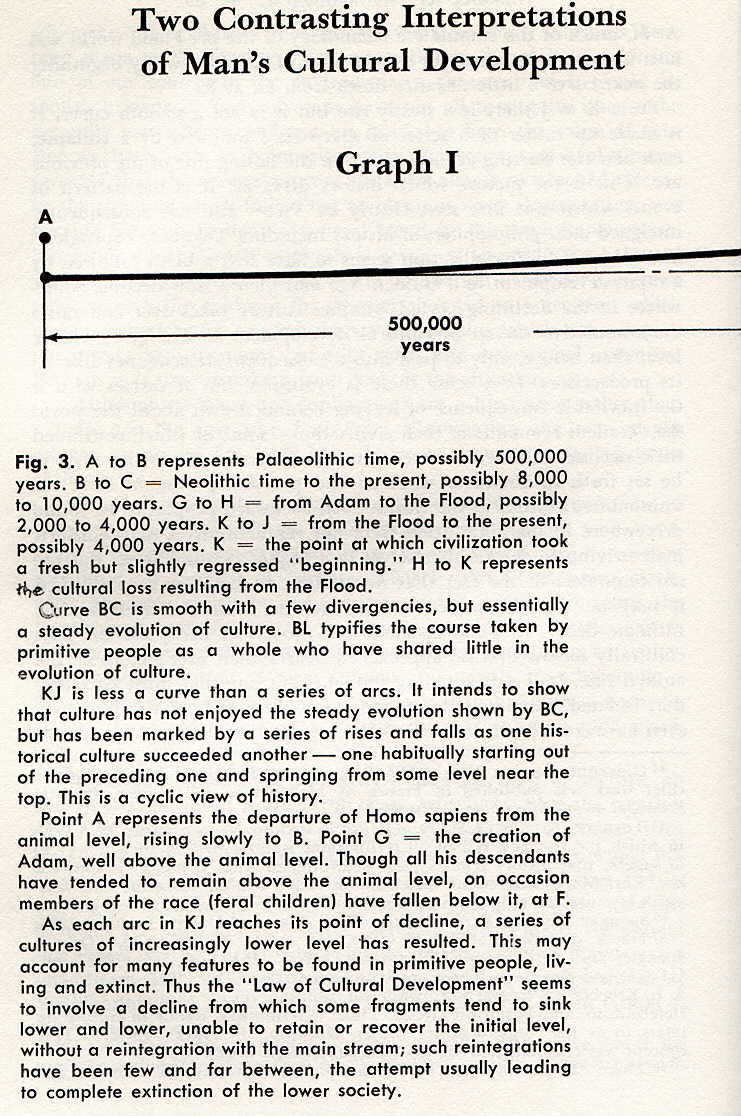

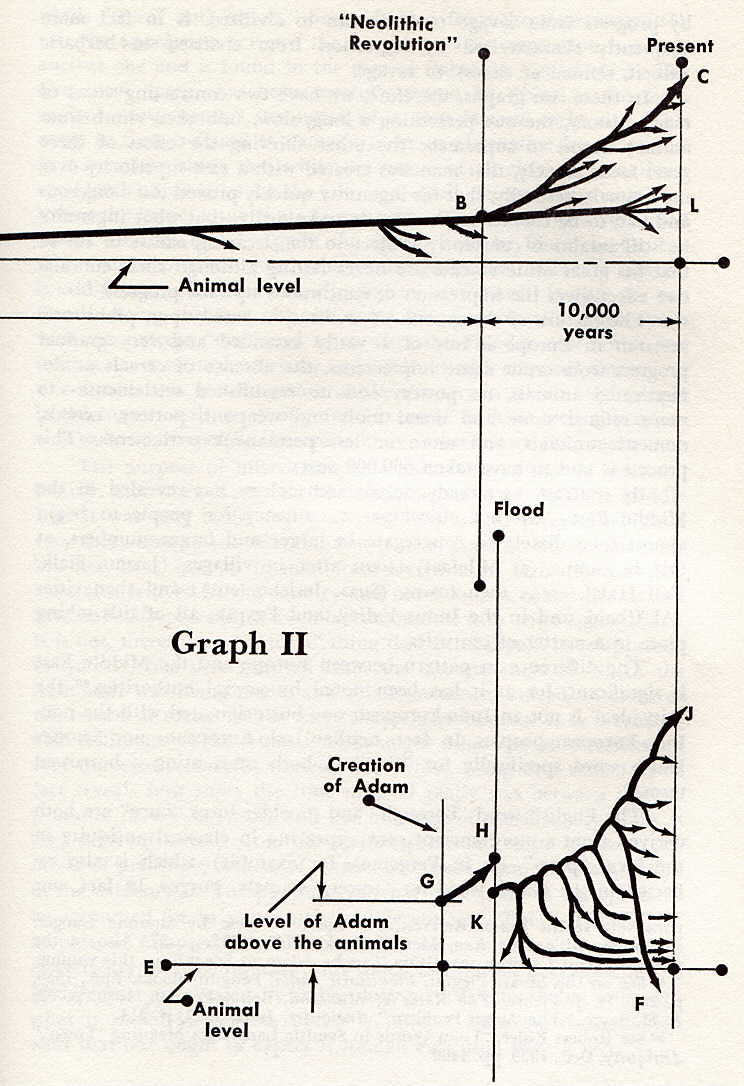

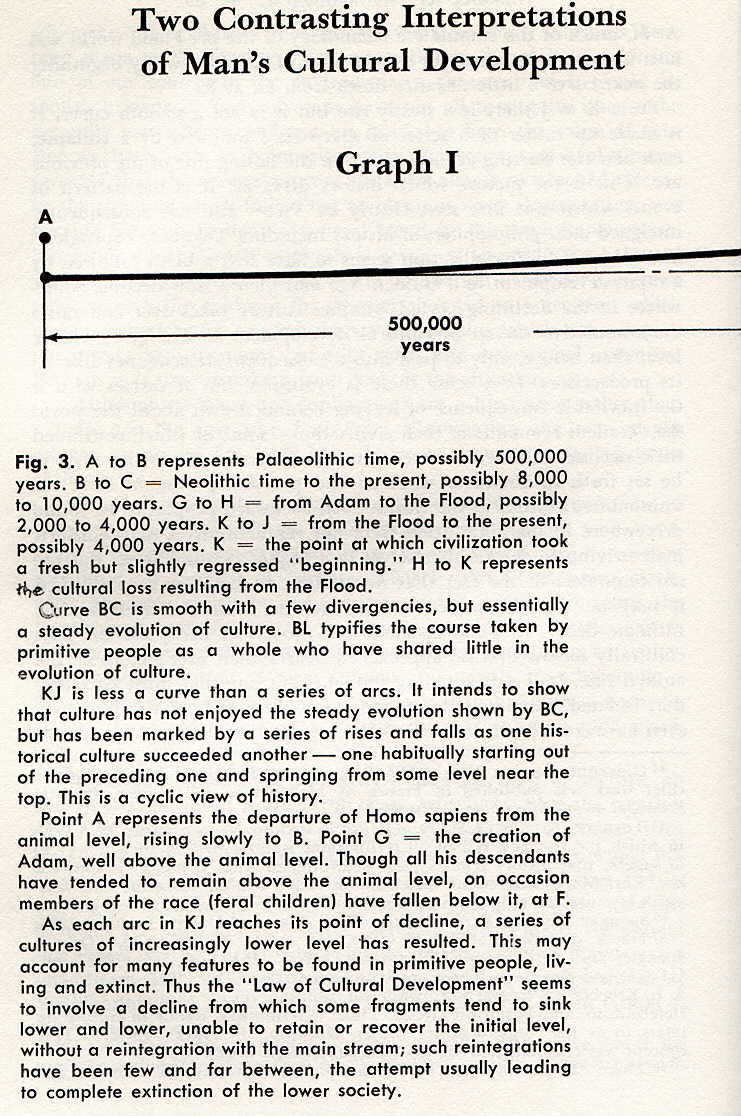

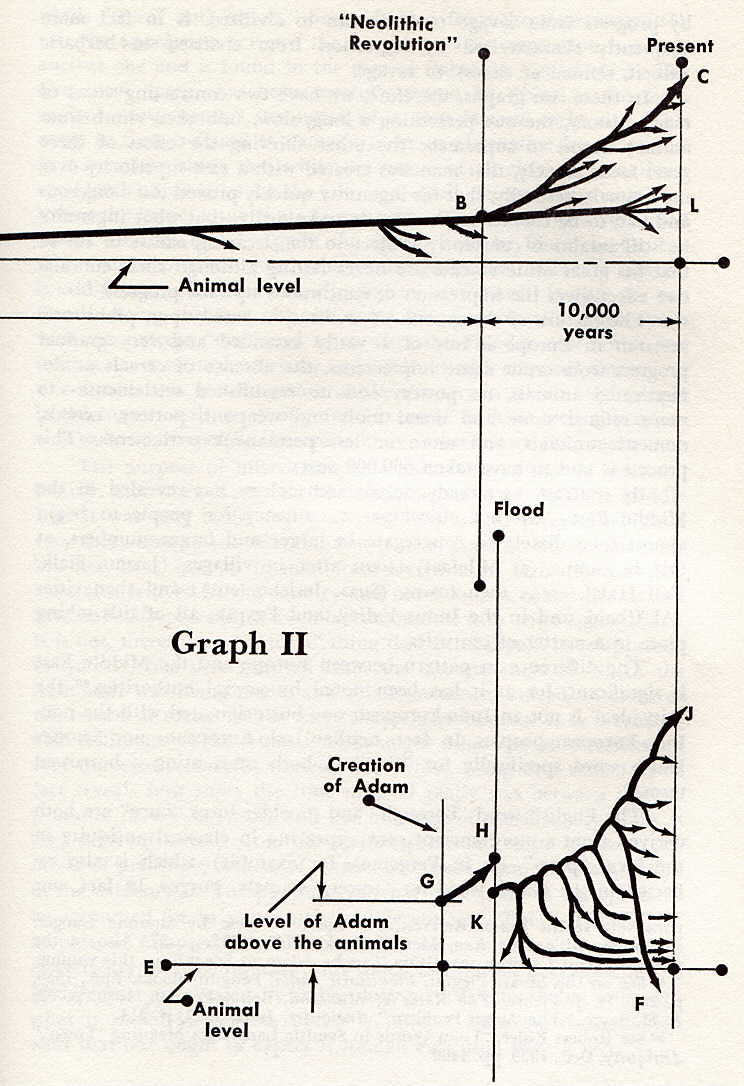

Although to many people diagrams

are a hindrance rather than a help, for the few who find them

illuminating the two graphs (Figure 3) have been drawn to summarize

the substance of the previous paragraphs.

Graph I in Figure 3 is intended to represent the currently accepted

view of things. The first man started at an animal level (A)

but with something which enabled him gradually to elevate himself

until he reached (B) after an interval of perhaps 500,000 years.

This point marks what has been called by some archaeologists

and prehistorians the Neolithic Revolution. (43) It is essentially the time at which man is believed

to have established the first permanent settlements by achieving

the domestication of some animals and cereals, thus becoming

a food producer for the first time. Previously man had been a

nomadic hunter. From this point on a steady cultural evolution

took place, occupying perhaps 10,000 years up to the present

time.

In Graph II of Figure 3 we have

an entirely different kind of picture, although the end result

is much the same. At (G) we have the creation of Adam already

removed far above the animal level. He began with certain instructions

from his Creator, certainly in language which lies at the root

of culture, and perhaps in the making of clothes and in the matter

of worship. These legacies and probably others were his from

the very first and (G) starts, therefore, clearly above the animal

line. From there to (H) which marks the time of the Flood was

a very rapid rise. The time interval is a matter of a very few

thousand years, contrasting sharply with the length of the line

AB in Graph I.

43. I think the originator of this term was

V. Gordon Childe. He uses it, for example, in his Man Makes

Himself, Watts, London, 1948, Chap.5, pp.66 following.

pg.2

of 22 pg.2

of 22

At H, much of the cumulative

technology of the pre-Flood world was lost: but much remained

for a fresh start. This is shown by beginning the next curve

a little distance down from H, at K.

From K to J there is a steady rise

but it is not a smooth curve. It is made up rather of a series

of sharp rises followed by a collapse, each new rise starting

at some point on the falling line of the previous arc. This is

the picture which history gives us: it is the pattern of events

which was first seen clearly by Vico (44) and has subsequently intrigued most philosophers

of history including Toynbee, (45) Spengler (46) and others. (47) Each civilization seems to have had a birth followed

by a rapid development to a Golden Age and then a slow decline.

Somewhere in the declining period, another culture takes over

and raises the cumulative thread of cultural development to a

slightly higher level than before, only to pass into a subsequent

descendancy like all its predecessors. In a sense there is evolution,

but it carries with it the inevitable consequence of leaving

behind strewn about the world the decadent remnants of each civilization

-- some of which continued their decline until rediscovered centuries

later by the White Man as he set forth to dominate what he had

previously thought were the uninhabited regions of the world.

Such backward peoples as he found everywhere in marginal areas

were not representatives of prehistoric man striving to elevate

themselves to a higher cultural level, but the sad reminders

of the fact that no civilization however accomplished it may

be, has the power within itself to maintain itself against ultimate

decay. In some instances the process of decay carried man culturally

so low that he approached nearer than ever before to the animal

line. It is a frightening thought, but one that must be faced,

that isolated individuals found now and then as feral children

may even have crossed this line also. (48) History, far from being characterized

44. Giovanni, Battista Vico (1668-1744) was

an Italian philosopher whose chief work was published in France

by Michelet in 1827 under the title Principes de la Philosophie

d'Histoire.

45. Toynbee, Arnold, A Study of History, Oxford University

Press, 1946-1957, in which the rise and fall of 19 civilizations

is presented in such a way as to suggest that history repeats

itself according to what is almost a spiritual law. Karl Marx

believed the determining factor was an economic one, Ellsworth

Huntingdon that it was a climatic one.

46. Spengler, Oswald, Decline of the West, Allen and Unwin,

London, 1926.

47. For a discussion of Vico's views see R. G. Collingwood, "Oswald

Spengler and the Theory of Historical Cycles," Antiquity,

Sept., 1927, pp.311.325; and also "The Theory of Historical

Cycles," Dec., 1927, pp.435-446. A. L. Kroeber has

several worthwhile contributions on the subject of Cultural Determinism

and Historical Cycles. These deterministic trends in culture

he refers to as the "superorganic," American Anthropologist,

vol.19, 1917, p.162-213, This concept was elaborated in many

of his subsequent works.

48. There are possibly four or five fairly well authenticated

cases in comparatively recent times. Reference is made to these

by Susanne Langer, Philosophy in a New Key, Mentor Books,

New York, 1952, p.87. Also in the works of Ernst Cassirer: see

"Who Taught Adam to Speak?" Part VI in Genesis and

Early Man, vol.2 in The Doorway Papers Series.

pg.3

of 22 pg.3

of 22

pg.4

of 22 pg.4

of 22

by progress from savage

to barbarian to civilized, is in fact more frequently characterized

by regression from civilized to barbaric (albeit, refined at

times) to savage.

In these two graphs, therefore,

we have two contrasting views of man's history, the one presenting

a long, slow, unbroken climb from animal almost to superman:

the other showing the effect of three great facts, namely, that

man was created with a vast superiority over the animals; secondly,

that his ingenuity quickly proved too dangerous and had to be

curbed by the Flood; and thirdly, that what ingenuity he still

retains is constantly subject to the decaying effects of sin

so that his great achievements are never lasting although their

cumulative effect gives the impression of continuous upward progress.

The picture of the growth of civilization

based upon prehistoric research in Europe is one of a vastly

extended and very gradual progress from crude stone implements,

the absence of cereals or domesticated animals, no pottery and

no established settlements -- to more refined stone and metal

tools and weapons, pottery, cereals, domestic animals, and more

or less permanent settlements. This process is said to have taken

500,000 years.

By contrast, as already noted,

archaeology has revealed in the Middle East -- but not elsewhere

-- a tendency for people to begin almost immediately to congregate

in larger and larger numbers, at first in camps (at M'lefaat),

soon after in villages (Jarmo, Sialk, Tell Halaf, etc.), then

towns (Susa, Jericho, etc.), and then cities (Al Ubeid, and in

the Indus Valley, and Egypt), all of this taking place in a matter

of centuries.

The difference in pattern between

Europe and the Middle East is significant, for as it has been

noted by several authorities, (49) the "city-idea" is not an Indo-European

one but originated with the non-Indo-European peoples. In fact,

neither Indo-Europeans nor Semites had a word specifically for

"city," in both cases using a borrowed term. (50)

The English word "borough"

and its older form "burg" are both derived from a more

ancient root appearing in classical antiquity in the form "perg-"

(as in Pergamos, for example) which is also reflected in the

Greek word for "tower," namely, purgos. In fact,

our words

49. See on this Stuart Piggott, Prehistoric

India, Penguin Books, Eng., 1950, p.263; H. J. Fleure, The

Races of Mankind, Benn, London, 1930, p.68; A. H. Sayce,

"The Aryan Problem," Antiquity, June, 1927,

p.214.

50. See Robert Eisler, "Loan Words in Semitic Languages

Meaning 'Town,'" Antiquity, Dec., 1939, pp.449 ff.

pg.5

of 22 pg.5

of 22

"town" and

"tower," being derived from the same root, indicate

the association between the two ideas. This association is a

very ancient one and is found in the case of Babel, in Genesis

11:4. The root form "perg" has been carefully

traced by Eisler to the more ancient word "uruk,"

the name of a very famous early city. This name in turn is found

in Cuneiform in an alternative form "unuk."

It is a curious thing that while the names of all cities in Cuneiform

are identified as cities by the use of a small determinative

sign preceding the name, unuk is a sole exception. There

must be a very good reason for this, and I suggest the reason

is to be found in Genesis 4:17. Cain, representing only the second

generation of Homo sapiens, is said to have built the

first city and to have named it after his son Enoch. Being the

first city, its name became virtually synonymous with the concept

"city" and when after the Flood a new Unuk was built

it never seemed necessary to identify it with a special determinative

sign. It was not altogether unlike the way in which local people

in the country will speak of going "to town" without

feeling it necessary to be more specific. Everyone knows which

town they mean.

The purpose of introducing this

point here is that it indicates, I think, that when Noah and

his family began to re-populate the Middle East it was only to

be expected that they would proceed within a very short time

to the re-establishment of villages or towns, since city life

had been normal to man from the time of Cain. People who have

always lived in the country and never known urban life do not

automatically proceed to assemble themselves into large aggregations.

It is not, therefore, a "natural" thing that cities

should have appeared so quickly, but they resulted from the circumstances

in which the fresh start was being made, and this is evidence,

indeed, in favour of the record of events in the early chapters

of Genesis. It is a remarkable testimony of the truth of what

might otherwise be considered a very innocent remark in Genesis

4:17, which being thus shown to be fact reveals how short the

time interval really was between the appearance of the first

man and the building of the first city. This is very different,

surely, from the picture presented to us in most textbooks of

prehistory which, of course, are based upon an examination of

the evidence in Europe. Perhaps what took place in Europe must

be accounted for in some entirely different way. This is the

subject, in part, of Chapter 3. In the meantime we may say with

a measure of certainty that the rapidity with which civilization

developed in the Middle East as revealed by archaeology accords

remarkably well with what is stated in Genesis but is in almost

complete contradiction with what one ought to expect if human

evolution were a fact.

pg.6

of 22 pg.6

of 22

But

we may go even further and say that not only did civilization

appear suddenly, but in many ways its earliest stages of development

tended to be its finest. One of the surprises of early archaeology

in the Middle East was the discovery that in the very area in

which man was supposed to have begun what Crawford has termed

"the conquest of culture," (51) there was no truly primitive stage even in such sites

as Sialk and Jarmo, and in the very lowest levels at Jericho

and Tell Halaf there is evidence of the rudiments of civilized

life though naturally at a simple level. But the domestication

of animals, the growing of wheat, and skill in the manufacture

of weapons and tools is there at the outset. Long antecedent

periods of development from an entirely nomadic food-gathering

kind of life to the community life of these early settlements

is, of course, assumed but is still unsupported by evidence.

A. H. Sayce in 1899, in spite of the fact that he knew nothing

of the subsequent finds in the Iranian Plateau to the north of

Assyria, was still essentially correct when he said, (52)

The history of the ancient East

contains no record of the development of culture out of savagery.

It tells us indeed of degeneracy and decay in time, but it knows

of no period when civilization began. As far as archaeology can

teach us the builders of the Babylonian cities, the inventors

of the cuneiform characters had behind them no barbarous past.

When these words

were penned, it was still confidently asserted by others that

further excavation would change the picture, and that in the

end it would become apparent that this great cultural surge which

marked the beginning of the truly historical period had a perfectly

"normal" (by which was meant evolutionary) development

from a primitive stage such as marginal groups possess. For this

development it was necessary to postulate thousands of years,

for in other areas where Stone Ages were known, progress from

the lowest levels to a high state of civilization was felt to

have taken literally hundreds of thousands of years. On the other

hand, while such sites as Jarmo and others do reveal an initially

simple stage, the time taken to reach a zenith of cultural achievement

can be measured in centuries, not millennia, much less hundreds

of thousands of years, evidently something different was taking

place at the center.

Let us deal with areas, one at

a time, and see what the authorities have to say. Since Egypt

is so familiar to us all (but not because of any priority in

time), let us begin with a review of the evidence

51. Crawford, M. D. C., The Conquest of

Culture, Fairchild, New York, 1948, xii and 449 pp., index.

A very useful summary of technical achievements, but without

documentation.

52. Sayce, A. H., Early Israel and the Surrounding Nations,

London, 1899, p.270.

pg.7

of 22 pg.7

of 22

from the valley of the

Nile. P. J. Wiseman said in this connection, (53)

No more surprising fact has

been discovered by recent excavation than the suddenness with

which civilization appeared in the world. Instead of the infinitely

slow development anticipated, it has become obvious that art,

and we may say science, suddenly burst upon the world. For instance,

H. G. Wells acknowledged that the oldest stone building known

to the world is the Sakkara Pyramid. Yet as Dr. Breasted pointed

out, "From the earliest piece of stone masonry to the construction

of the Great Pyramid less than a century and a half elapsed."

Writing of this Pyramid, Sir Flinders

Petrie stated that "the accuracy of construction is evidence

of high purpose and great capability and training. In the earliest

pyramid the precision of the whole mass is such that the error

would be exceeded by that of a metal measure on a mild or a cold

day: the error of leveling is less than can be seen with the

naked eye. The conclusion seems inevitable that 3000 B.C. was

the heyday of Egyptian art."

Dr. Hall in referring to this sudden

development says, "It is easy to say that this remarkable

outburst of architectural capacity must argue a long previous

apprenticeship and period of development: but in this case we

have not got this long period."

In the face of these facts the

slow progress of early man is a doubtful assumption, and the

idea that an infinitely prolonged period elapsed before civilization

appeared cannot be maintained.

G. A. Reisner

says that the quality of "the art of the Old Kingdom of

Egypt . . . has rarely been reached by the art of any other period

or region: but authentic specimens are not common, and popular

judgment is usually formed by inferior examples of later

ages." (54)

Vere Gordon

Childe in speaking of early Egyptian pottery remarked: (55)

The pottery vessels especially

those designed for funerary use, exhibit a perfection of technique

never excelled in the Nile Valley. The finer ware is extremely

thin, and is decorated all over by burnishing before firing,

perhaps with a blunt-toothed comb, to produce an exquisite rippled

effect that must be seen to be appreciated.

Walter Emery,

speaking of the tombs of the first Pharaohs, remarked: (56)

One great tomb after another

was cleared (from 1935 to the end of World War II) each showing

that civilization during the period of the First Dynasty was

far more advanced than we had supposed . . . showing that a highly

developed culture existed in Egypt by 3000 B.C. . . .

53. Wiseman, P. J., New Discoveries in

Babylon About Genesis, Marshall, Morgan and Scott, London,

2nd edition, revised, undated, pp.28, 31, 33.

54. Reisner, G. A., The History of the Giza Necropolis, reviewed

in Antiquity, Mar., 1938, p.104.

55. Childe, Vere Gordon, New Light on the Most Ancient East,

Kegan Paul, London, 1935, p.67.

56. Emery, Walter B., "The Tombs of the First Pharaohs,"

Scientific American, July, 1957, pp.107, 112, 116.

pg.8

of 22 pg.8

of 22

The scattered

contents of their tombs show that they had a well developed written

language, a knowledge of the preparation of papyrus, and a great

talent for the manufacture of stone vessels, to which they brought

a beauty of design that is not excelled today. They also made

an almost unlimited range of stone and copper tools, from saws

to the finest needles. Their decorative objects of wood, ivory,

and gold are masterly, and their manufacture of leather, textiles,

and rope was of a high standard. Above all they had great artistic

ability.

This advanced civilization appears

suddenly in the early years of the third millennium B.C.; it

seems to have little or no background in the Nile Valley. . .

.

The monumental architecture of

the First Dynasty has been compared to that of the Jamdet Nasr

period in Mesopotamia, and I think the similarity is beyond dispute.

This Jamdet

Nasr period is dated around 3500 B.C. by Meek, (57) being the last of four pre-Dynastic periods in Mesopotamia

of which the first was the Al Ubeid period to which reference

is made subsequently.

R. E. Bewberry pointed out that

"the essentials of the Egyptian system of writing were fully

developed at the beginning of the first dynasty. It must have

been the growth of many antecedent ages, yet not a trace of the

early stages of its evolution have been found on Egyptian soil."

(58) Vere Gordon

Childe put it this way: (59)

On the Nile and in Mesopotamia

the clear light of written history illumines our path for fully

fifty centuries, and looking down that vista we already descry

at its farther end ordered government, urban life, writing, and

conscious art. The greatest moments -- that revolution when man

ceased to be a parasite . . . have passed before the curtain

rises.

W. J. Perry,

quoting de Morgan, (60)

said, "What appears at a very early date in Egypt is perfection

of technique. The Egyptian appears, from the time of the earliest

Pharaohs, as a patient, careful workman, his mind like his hand

possesses an incomparable precision . . . a mastery that has

never been surpassed in any country."

Of course, archaeologists have

turned up some ancient remains which seem to be more simple and

more like the Paleolithic remains of Europe, yet even in these

sites pottery is found, and of this pottery W. E. Taylor of the

University of Toronto assured us that "crude as it may appear

it was in actual workmanship never excelled. The flint

tools chipped and ground so very carefully are the finest that

have ever been found anywhere!" (61) It may be strange to refer to their

57. Meek, T. J., "Magic Spades in Mesopotamia,"

University of Toronto Quarterly, vol.7, no.2, Jan., 1938,

p.235 237.

58. Bewberry, R. E., quoted by C. Urquhart, The Bible Triumphant,

Pickering, London, 1935, p.36.

59. Childe, V. G., New Light on the Most Ancient East, Kegan

Paul, London, 1935, p.2.

60. Perry, W. J., The Growth of Civilization, Pengin Books,

England, 1957, p.54.

61. W. E. Taylor in a lecture given before the Orientals Dept.

of the University of Toronto, Spring of 1936.

pg.

9 of 22 pg.

9 of 22

pottery as crude and yet as never

excelled . . . but the fact is that Egypt did not possess a source of

clay for good pottery, and thus their best efforts were not comparable

to the pottery of other ancient civilizations. Nevertheless, the best

they ever made was made at the very beginning.

Moving northward from Egypt, towards

the Cradleland, we come to Palestine and then to Syria. It is

fairly certain that those who entered Egypt came either around

the Fertile Crescent from Mesopotamia following the natural route

which was followed by Abraham, settling first in the Nile Delta

towards the sea and then subsequently settling the Upper Nile

and Ethiopia, or across Southern Arabia to the Horn of Africa

and flooding out across the African continent.

Although it is not usual to look for

the origins of culture in Palestine, it will be valuable in passing

to note a remark by M. G. Kyle with respect to the pre-Israelite

times, when the country was possessed by the Canaanites and the

Philistines and other tribes mentioned in the early chapters

of Genesis. He said: (62)

Wherever it has been possible

to institute a comparison between Palestine and Egypt, the Canaanite

civilization in handicraft, art, engineering, architecture, and

education has been found to suffer only by that which climate,

materials, and locality impose. In genius and in practical execution

it is equal to that of Egypt and only eclipsed, before Graeco-Roman

times, by the brief glory of the period of Solomon.

To the north

lay Syria. The recent excavations at Ras Shamra and more especially

at Tell Halaf have revealed much of the wealth and culture of

the very earliest periods. This is particularly and, for our

purposes, significantly true of the very earliest period at Tell

Halaf. T. J. Meek in discussing the achievements reached by the

people who occupied the site at the very beginning remarked:

(63)

Tell Halaf has revealed

the most wonderful hand-made pottery ever found. Although the

lowest strata here are probably representatives of the oldest

culture so far definitely attested, yet it is already clearly

chalcolithic. From various indications we know that metal was

used, although not very extensively. In this period great skill

was shown in the working of obsidian into knives and scrapers...The

pottery of Tell Halaf was made by hand, unbelievably thin, indeed

not thicker than two playing cards, and shows an extraordinary

grasp of shape and decorative effect in color and design. The

pottery was fired at great heat in closed kilns that permitted

indirect firing with controlled temperatures. The result of the

intense heat was the fusion and vitrification of the silicates

in the paint so that it

62. Kyle, M. G., "Recent Testimony of

Archaeology to the Scriptures," in The Fundamentals,

Biola Press, Los Angeles, 1917, p.329.

63. Meek, T. J., "Mesopotamian Studies," in The

Haverford Symposium on Archaeology and the Bible, 1938, p.161.

pg.10

of 22 pg.10

of 22

became a genuine glaze that gives the surface

a porcelain finish quite different from the gloss of burnished ware

so common later.

Technically and artistically the

Tell Halaf pottery is the finest handmade pottery of antiquity

and bears witness to the high culture of its makers.

Mallowan said

of the use of metal at this early period, "It should be

noted that in one of the oldest strata in which Tell Halaf pottery

occurs, a copper necklace-bead has been found." (64)

The people who came to Tell Halaf

and thus began the civilization of Syria and Palestine, evidently

arrived from two directions. Some seem to have come from the

north, from Anatolia, and possibly some from Mesopotamia due

east, i.e., from northern Babylonia. We must look further to

the east, therefore, for the roots we are seeking.

Turning to the Mesopotamian plains,

the story is exactly similar to the story of Egypt. The greatness

of Egypt is monumental. The greatness of Sumerian civilization

is of a different nature. Despite the fact that they had no stone

with which to erect memorials of their culture as Egypt erected

theirs, yet once the search had begun it became increasingly

apparent that not only was Sumerian civilization equal in every

respect to that of Egypt, it was prior. The earliest culture

of the long series which culminated in the great cities like

Nineveh and Babylon is termed the Al Ubeid Culture. Of these

people Vere Gordon Childe wrote: (65)

The authors of the Al Ubeid

culture cannot have sprung from the marsh bottom, yet the culture

itself shows no sign of having developed locally from any more

primitive Mesolithic forerunner.

C. J. Gadd remarked:

(66)

The Sumerians possessed

the land since as far back in time as anything at all is seen

or even obscurely divided, and it has already been remarked that

their own legends which profess to go back to the creation of

the world and of men, have their setting in no other land than

their historical home. . . . But the shapes of the earliest

flints are not those of a pure stone age, nor has any certain

evidence been found in Iraq of a population so primitive as to

have no knowledge of metal.

And again, subsequently,

he said: (67)

Works of art which astonish

by their beauty have been found (not least at Ur itself) to be

the relics of the first, not the last ages. Nothing but the good

fortune that they were discovered by regular

64. Mallowan, M. E. L., The Excavations

at Tell Chagar Bazar and an Archaeological Survey of the Habur

Region, 1934-35, Oxford, 1936, reviewed in Antiquity,

Dec., 1937, p.502.

65. Childe, V. G., ref.55, p.145.

66. Gadd, C. J., The History and Monuments of Ur, Chatto

and Windus, London, 1929, p.24 and p.17.

67. Ibid., p.27.

pg.11

of 22 pg.11

of 22

excavation could have avoided the ludicrous misconception

of their date. . . . Gold is the material of their possessions

and the symbol of their superfluity. In the flourishing days and at

their lavish court, the arts of manufacture rose to a perfection and

beauty in their products which was never seen again. The articles made

were, indeed, of much the same kind as those of later ages, but they

were at this very early period marked by a richness and splendor rather

of Egyptian sumptuousness than the supposed sobriety of the River-lands.

These deposits amaze by their riot of gold: silver also is there in

great profusion evidently nothing accounted of.

Sir Leonard

Woolley (68) came

to the conclusion that "so far as we know, the fourth millennium

before Christ saw Sumerian art at its zenith." And Childe

likewise remarked upon the same phenomenon, (69) "These (recent discoveries) suffice to show

that, even more than in Egypt, civilization has reached a very

high level by the end of the fourth millennium B.C., that was

not surpassed during the whole of the pre-Sargonid epoch."

And Wiseman pointed out: (70)

This discovery is the very opposite

to that anticipated. It was expected that the more ancient the

period the more primitive would excavators find it to be, until

traces of civilization ceased altogether and aboriginal man appeared.

Neither in Babylonia, nor Egypt, the lands of the oldest known

habitations of man, has this been the case. In this connection

Dr. Hall writes in his History of the Near East, "When

civilization appears it is already full grown." And subsequently,

"Sumerian culture springs into being ready made." And

Dr. L. W. King in his book Sumer and Akhad remarks, "Although

the earliest Sumerian settlements in southern Babylonia are to

be set back in a comparatively remote past, the race by which

they were founded appears at that time to have already attained

to a high level of culture."

Yet it is not possible to push

back the habitation of man in the Mesopotamian plain vast millennia

into the past, for the very simple and conclusive reason that

the more southern Mesopotamian land must have been formed within

the last 10,000 years or so. We know that owing to the peculiar

nature of the rivers in bringing down silt, and depositing it

at the entrance to the Persian Gulf, the land has been formed

gradually during the past few thousand years, and the land is

still being added to by this means. Ur of the Chaldees was once

on the edge of the Persian Gulf, and is now over one hundred

miles from it.

J. L. Myers

pointed out that the shore line has been advancing rapidly within

historic times: Eridu, for example, which was a chief port of

early Babylonia, lies now 125 miles from the sea. (71) If the present rate of

advance, about a mile in thirty years, may be taken

68. Woolley, Sir Leonard, The Sumerians,

Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1928, p.44.

69. Childe, V. G., New Light on the Most Ancient East, Kegan

Paul, London, 1935, p.19.

70. Wiseman, P. J., New Discoveries in Babylon About Genesis,

Marshall, Morgan and Scott, London, 2nd edition, revised, undated,

pp.28 and 29.

71. Myers, J. L., Dawn of History, Williams and Norgate,

London, undated, p.85.

pg.12

of 22 pg.12

of 22

as an average, Eridu may have begun

to be mud-bound about 1800 B.C.

T. J. Meek in a lecture given at

the University of Toronto stated that "the Sumerian culture

springs into view ready made, and there is yet no knowledge of

the Sumerians as savages: when we find them in the fourth millennium

B.C. they are already civilized highly. They are already using

metals and living in great and prosperous cities." (72) Citizens stamped their

correspondence with cylinder seals that were rolled over the

soft clay. Such seals were beautifully carved in the very ancient

times with animal figures that portray motion. The later seals,

even those of only a few centuries later, are vastly inferior

from an artistic point of view. Inspiration belonged to the earliest

ages, not to the later. (73) When compared with their present descendants, if

brain size means anything, according to Sir Arthur Keith even

in this they were superior. (74)

Now the record of Genesis tells

us that those who first settled in Mesopotamia entered the land

"as they journeyed from the East." This implies that

they did not originate there; and since this piece of historical

information is presented to us some time after the Ark had landed,

and after men had begun to spread abroad somewhat, it seems fairly

certain that these people had come down on the eastern side of

the Zagros Mountains towards the site of Susa. Here they effected

a settlement before going on towards the west and there "finding"

a plain, the plain of Mesopotamia. Susa thus stands in a parental

or at least a prior relationship to the Al Ubaid culture exactly

as the excavations show. We ought in theory to be one step nearer

the beginning when we have arrived back at Susa.

Yet even here, the story is repeated.

H. G. Spearing wrote of Susa: (75)

The earliest colonists at Susa

were well civilized before they left the country of their parenthood

and arrived there. For in their burial ground outside the city

walls are found the bronze hatchets of the men and the mirrors

and needles and the ointment vases of the women; there are also

relics of delicate fabrics finely woven on a loom. . . .

The pottery is wonderfully thin

and hard, not much thicker than a couple of post cards, and it

rings like porcelain, though it is not so

72. Meek, T. J., in a lecture before the Orientals

Dept., University of Toronto, Fall of 1936.

73. Frankfort, Henri, in an article on Khafaje in the Illustrated

London News, Nov. 13, 1937, pp.840, 841, gives some photos

of such seals.

74. Keith, Sir Arthur, "Physical Anthropology," Science

Progress, Oct., 1936, p.333.

75. Spearing, H. G., "Susa, The Eternal City of the East,"

in Wonders of the Past, vol. 3, Putnam, New York, 1924,

p.583.

pg.13

of 22 pg.13

of 22

transparent. The forms are simple and graceful;

they were produced on a rudimentary pottery wheel used with a skill

that looks like the inherited experience of many generations of craftsmen.

Nearly all the bowls and vases

were elaborately decorated either inside or outside with strange

designs, most of which have no similarity with other designs

found in other parts of the world, so that we have no clue to

the country where these potters learned their art, though we

can be fairly sure that they brought it from some center of civilization

where it had been undergoing a long period of development.

How inevitable this conclusion always seems

to be!

Where shall we look now for the

origins of the people who created this pottery? It seems we cannot

look further to the east, though in this direction lies the Indus

Valley Civilization. But this culture owes its origin to a people

who themselves manifestly came from the west, and who shared

much with the creators of the Sumerian culture. Nevertheless,

the earliest levels at two sites, Changu Daru and Harappa in

the Indus Valley, are remarkably reminiscent of the earliest

levels at Tell Halaf in Syria, and in keeping with the fact that

the Tell Halaf settlers arrived there from the north and east

towards Ararat, it is clear that the Indus Valley people came

from somewhere in the same direction. Thus Ernest Mackay (76) said, "There seems

no doubt that . . .we must look to the Iranian Highlands for

the region whence civilization was brought to India."

In his report to the Illustrated

London News, Mackay remarks upon the finds at the earliest

levels in Changu Daru, (77) and describes the extraordinary way in which the

city was laid out in blocks with draining systems and underground

sewers. Some of the drain pipes are illustrated in his article

and he remarks of them that they "are quite modern in design

. . . some having spigots which fit into each other, and some

conical shaped so that the smaller end fits into the larger end

of the next one."

He tells of a hoard of beads found.

(78)

Some of the beads made of steatite

were astonishingly small; a quantity had been kept for safety

in a small jar, and when placed end to end they ran to 34 to

an inch. Their holes were so tiny that they could only have been

threaded on a hair, and how these beads were made and bored it

is hard to comprehend. . . .

As at Mohenjo Daro (another Indus

Valley site) practically every house had its bathroom and latrine

from which the water ran into the street drains and was thus

carried well outside the city. Indeed, the draining system was

remarkably well planned, every street being supplied with two

or more drains, built, like the houses, of burnt brick. A number

of pottery drain pipes, some of which were found in situ,

76. Mackay, Ernest, "Great New Discoveries

of Indian Culture in Prehistoric Sind," Illustrated London

News, Nov. 14, 1936, Plate I.

77. Ibid., p.860, Fig.II.

78. Ibid., pp.860 and 894.

pg.14

of 22 pg.14

of 22

testify that these ancient people were expert

sanitary engineers; moreover, falls were arranged so that there should

be as little splashing as possible, and when a corner had to be turned

the bricks were carefully rounded off to reduce friction. The drain

pipes are quite modern in design; except for being made of porous pottery,

they would well serve the same purpose today.

As a matter

of fact, anyone who has had experience with a septic tank disposal

system will know that in reality this porosity was a great advantage,

for much of the content of the system is bled through the pipe

walls into the surrounding soil, thus relieving the load at the

disposal end.

Some remarkable seal amulets were

also found at the lowest levels, with illustrations of elephants,

oxen, and single-horned Urus ox. These seals are beautifully

carved, with almost perfectly formed reproductions of the animals

they portray, showing absolutely correct proportion and musculature.

Copper and bronze instruments and weapons abound everywhere.

How well such sanitation and such

household furnishings contrast with the modern eastern villages

whose inhabitants have the unpleasant habit of casting all refuse

into the street for the rain to wash away. But where did these

people come from? Dr. Mackay says we must look towards the Iranian

highland plateau. Wherever they came from, it seems they entered

the Indus Valley already cultured. It is amazing to find at two

of the earliest sites, Harappa and Changu Daru, evidence of such

artistic taste and skill, coupled with a remarkable engineering

knowledge.

At Mohenjo Daru, another site in

the same complex, was found a male dancing figure and the torso

of a nude female figure which, according to Childe, (79) are "modelled with

a liveliness of attitude, and the musculature and contours of

the bodies delineated with an attention to detail and verisimilitude,

found nowhere else before classical Greek times. Indeed so modern

is the treatment that the sculptures have been attributed to

the Greco-Bactrian age." Their artistic taste was no less

highly developed than their technology.

But if these settlers came from

the highland zone surely we ought to find their remains there?

It seems that the site of Sialk is such a village. Excavation

of this site was undertaken by a French expedition from the Louvre

Museum, beginning in 1933 and working continuously till 1938,

and with further work in the area since World War II. In charge

of the expedition was R. Ghirshman who has reported his

79. Childe, Vere Gordon, "India and the

West Before Darius," Antiquity, Mar., 1939, p.10.

pg.15

of 22 pg.15

of 22

work in numerous journals and recently

given a very comprehensive account in a volume entitled "Iran."

(80)

In this, and in earlier papers,

he set forth some of his findings as follows. The site is quite

near the famous city of Kashan known for its rugs, and not far

south of Teheran the capital of Iran. It was first occupied in

the fifth millennium B.C., at which time the evidence shows that

the climate of the region was just changing from a very wet one

to an arid one. The central part of the Iranian highland plateau

had apparently escaped the glaciation which had engulfed the

rest of Europe but had been experiencing a very, very heavy rainfall,

and this had led to the formation of "an immense lake or

inland sea" into which many rivers ran from the high mountains.

As this large, but shallow, inland sea dried up it left in its

place many swamps which became grassland and savannah. Game was

abundant and man "moved in first to hunt and then to settle

permanently." He had, by this time, already domesticated

certain species such as the ox and the goat.

Ghirshman also found that the occupants

were highly artistic. To use his own words: (81)

Never before in the systematic

explorations which have brought to light the remains of extinct

civilizations have such objects carved out of bone or of stone

been found in this region. The Sialk excavations have now revealed

the existence of a marvelous art of carving on bone, which had

already made noteworthy progress at the period we are now considering.

Among the remains of the dwellings, we found recently a whole

series of flint holders, with handles finished off with an animal

head or a carved human figure. . . .

The figurine which decorates the

handle of one of these tools may be regarded as the oldest carved

human image ever found in Western Asia. The statuette, which

perhaps represents a chief or a priest, has a little cap on its

head; round the hips is a loin-cloth, the upper part of which

is rolled under to form a sort of belt. The arms of the figure

are crossed, and the torso is slightly bent forward.

It is not possible to believe that

an art capable of creating such an object as this statuette was

in its initial phase. The artist reveals awareness both of proportions

and of technical approach. The way in which the attitude of the

man is treated, his muscles, his clothing, show close observation,

and also much practice and skill. . . .

The inhabitants

soon domesticated also pigs, dogs and the horse, this being the

first evidence of the existence of the latter in Iran at such

a remote period. Vere Gordon Childe remarked on the surprising

fact that at the earliest levels the inhabitants were also spinning

and weaving to make fabrics, though the fibers they used have

not yet

80. Ghirshman, R., Iran, Penguin Books,

Eng., 1954, 368 pp., Index, illustrations.

81. Ghirshman, R., "At Sialk: Prehistoric Iran," Asia,

Nov., 1938, p.646.

pg.16

of 22 pg.16

of 22

been identified for certain. (82)

Ghirshman also referred to the earliest known records in the form of simple

tablets which were clearly to be related with the earliest tablets found

by a French expedition in the lowest levels of Susa �- thus establishing

what he considers a direct ancestral link from the north to the south.

It seems therefore that Sialk represents

a settlement made by the people who, travelling further towards

the south, established themselves at Susa some little time later.

But Ghirshman would go one step further, for he views the people

of Sialk as being related also to the Indo-European civilization,

and to that of the Phrygians of Asia Minor, a people of the Indo-European

race closely related to the Illyrians who immigrated there from

Thrace, which "entitles us to regard the inhabitants of

Sialk as belonging also to the same Indo-European family."

(83) It is only

to be expected that there should be evidence at this early time

of the close association of all three of the sons of Noah. It

would almost seem as though they were still together at this

time, though doubtless their families had greatly enlarged. But

shortly afterwards they began to divide. The children of Japheth

went towards the north and settled up into Asia Minor and into

Europe. The children of Ham went south and coming into the Indus

Valley established themselves there. But they also went via Susa

round into Mesopotamia arriving at the southern end soon afterwards

to establish the Al Ubeid culture. Perhaps the children of Shem

went towards the west and then down into northern Syria, settled

at Tell Halaf and later turned towards the east again and to

northern Mesopotamia where in the time of Nimrod they fell under

the domination of the Sumerians from the south.

In speaking of Sialk, Childe is

careful to note how quickly the people who occupied it moved

forward in their civilization. He wrote: (84)

The earliest culture found at

Sialk can be matched at other sites upon the plateau and northward

up to Anau in the Merv oasis in Russian Turkestan [the route

followed by the children of Japheth?]. At Sialk a second phase

can be seen in the villages built on the ruins of those described.

The houses are no longer built just of packed clay, but of molded

bricks dried in the sun. Food-gathering is less prominent in

the communal economy: horses have been added to the domestic

flock. Shells are brought across the mountains from the Persian

Gulf. Copper is commoner, but it is still treated as a superior

sort of stone,

82. Childe, Vere Gordon, What Happened

In History, Penguin Books, Eng., 1946, p.64.

83. V. G. Childe also refers to the evidence for the existence

of a Japhetic people dwelling in early times in the highlands

from the Zagros Mountains westward (New Light on the Most

Ancient East, Kegan Paul, London, 1935, p.18).

84. V. G. Childe, What Happened In History, Penguin Books,

Eng., 1946, p.64.

pg.17

of 22 pg.17

of 22

worked by cold hammering. Equipment is made from

local bone, stone and chert, supplemented by a little imported obsidian.

But special kilns are built for firing pots.

Then with Sialk III the village

was removed to a new site close by the old one and watered by

the same spring. Equipment is still mainly home-made from local

materials. But copper is worked intelligently by casting to make

axes and other implements that must still be luxuries. Gold and

silver are imported, and lapis lazuli from northern Afghanistan.

Potters appear who make vessels quickly on a fast spinning wheel,

instead of building them up by hand. And men use seals to mark

their property. Finally Sialk IV is a colony of literate Elamites.

. . .

In other words,

life at the very beginning in these places was necessarily simple,

but it seems that it was not only technically proficient it was

also artistic and therefore cultured. And it developed extremely

rapidly.

From Sialk it is now customary

to go back to the lower levels at Jarmo and to other sites in

Iraqi Kurdistan which appear to represent an earlier stage, a

stage without pottery (roughly contemporary with and similar

to the lowest levels of Jericho even though it was already a

fortified town by this time). (85) But can we really be sure that such sites are prior

merely because there is no evidence of pottery? Is this not a

biased interpretation? There is really no absolute reason for

placing these cultures "earlier" other than the argument

that they ought to be earlier merely because they appear to be

simpler. The supposed law of evolutionary development may demand

this interpretation, but in itself the evidence is quite neutral,

until something turns up which positively established priority.

When Noah and his family stepped

out of the Ark somewhere in this general region, they certainly

must have had a knowledge of metals, for by this time metal-working

was already centuries old (Genesis 4: 22).

Now, it is argued that sites without

pottery in this area must be earlier. The criterion is the absence

of pottery. However, it is known from other sites, especially

in Greece, (86)

that the use of metals can precede the use of pottery,

pottery vessels being subsequently based upon metal prototypes.

In such sites, although the metal originals have disappeared,

they must have existed in order to give rise to what are manifestly

substitutes. It follows from this that in those periods

85. For a useful summary of these associations

and time correlations, see Seton Lloyd, Early Anatolia,

Penguin Books, Eng., 956, pp.54.

86. Excellent illustrations of such pottery will be found in

E. J. Forsdyke, "Marvels of the Potter's Art," in Wonders

of the Past, vol. 2, Putnam, New York, 1924, Plate at p.426.

Such forms occur widely in early Heliadic sites as at Asea, Gournia,

Korakou, Vasiliki, etc. Even the rivets are sometimes reproduced

in pottery!

pg.18

of 22 pg.18

of 22

when vessels were commonly made

from metal, there may have been an absence of pottery, and this absence

would be evidence, not of a lower level of technology, but rather of a

higher one. Thus the reason why Jarmo and the lower levels of Jericho

are considered to be more primitive, i.e., the absence of pottery, may

be quite unsound. In fact, when pottery does finally appear in these sites,

it takes a form which could easily be the result of inspiration derived

from the use of metal wares. The fact that no metal wares were found at

these lower levels is not too significant for the simple reason that such

vessels would not be easily broken and would not be thrown away. The point

of this discussion is simply that those sites which by reason of their

lower culture are considered to be antecedent, may actually be later:

they may be, in fact, settlements established by the first offshoots from

the main body on the highland plateau.

Thus although Jarmo and early Jericho

are assumed to be older than Sialk, I do not think the point

is established. Possibly they were, but the assumption rests,

as stated above, on the lower level of cultural development as

gauged by what was left behind by the inhabitants. The dating

for Jarmo established by Braidwood is in any case not so very

ancient. He gives the figure 6000 B.C., but adds that this date

is likely to be reduced, when the evidence is more fully assessed.

(87) Jericho is

dated by Kenyon at 8000 B.C., (88) but Zeuner who was chiefly responsible for the investigations

on which the figures were based states "most emphatically"

that caution is needed in accepting these C-14 dates. (89)

Such then is the picture. Somewhere

in the Iranian highland there settled a small group of people

who needed little time to develop sufficiently to create the

later culture-complex which characterized the upper levels at

Sialk. From here, or from some similar sites in about the same

stages of development, emigrants set out towards the West to

settle at Tell Halaf, for example. Others went south, dividing

into two bands, one passing around the lower end of the Zagros

Mountains where they came up into the plains of Mesopotamia from

87. Braidwood, Robert J., "From Cave

to Village," Scientific American, Oct., 1952, pp.62

ff. This is an excellent summary with useful illustrations and

graphic presentations of the evidence as he sees it. To the uninitiated,

the matter is clearly settled. But Miss Kenyon disagrees.

88. Kenyon, Kathleen M., "Ancient Jericho," Scientific

American, Apr., 1954, pp. 76. In her article, "Some

Observations on the Beginnings of Settlement in the Near East,"

Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, Jan.-

June, 1959, pp.35 ff., she explains why she believes Jericho

is older than Jarmo and criticizes Braidwood's interpretation

of the Archaeological evidence from Jarmo -- which shows how

difficult it is to be certain about sequences at this early date.

89. Kenyon, Kathleen, Journal of the Royal Anthropological

Institute, Jan.- June, 1959, p.41.

pg.

19 of 22 pg.

19 of 22

the south, and the other turning

to the east, finally establishing themselves in the Indus Valley.

From Mesopotamia and Northern Syria

it seems, more adventurous spirits travelled on until they reached

Lower and Upper Egypt; and all this took place within a remarkably

short time. (90)

This is manifestly a gross over-simplification,

for some of the settlers, in lower Mesopotamia, subsequently

travelled around the southern boundary of Arabia and entered

Africa via the Horn. And the Japhetic branch of the family of

Noah quite possibly spread at a much more leisurely pace toward

the north (into the Caucasus) and towards the west (into Asia

Minor and on into Greece and Europe), only much later returning

towards the south and east into Persia and into the Indus Valley.

Yet even though this reconstruction is artificial in its simplicity,

the time factor is not likely to be changed very much. The tendency

has been, rather consistently, to reduce rather than to extend

the over-all chronology. (91)

All the initial movements seem

to have taken place within a period of about 1,000 to 1,500 years,

showing how quickly the transition was made to the cultural level

at Al Ubeid, for example. And while Al Ubeid stands at the beginning

of Sumerian civilization, within a few hundred years the Sumerians

had achieved a level of technical proficiency greater than that

to be found in many parts of Europe just prior to the Industrial

Revolution.

90. A very stimulating and concise evaluation

of the evidence for these early migrations was given by M. E.

L. Mallowan in "Mesopotamian Trilogy," Antiquity,

June, 1939, pp.159-170.

91. In discussing one of the papers presented at the Anthropological

Symposium (ref.29), Grahame Clark made the remark regarding new

techniques of dating, "They seem to suggest that the Magdalenian

cave artists, far from ending at 18,000 B.C., probably ended

at more like 8,000 B.C., and far from beginning anywhere near

so early as 50,000 B.C., began about 15,000 B.C., or perhaps

even later. I conclude by asking a question which I hope Hallam

Movius (see ref.18) will take up. If the only date in the Zeuner-Milankovitch

system (on which ref.92 is based) we are in a position to check

by means of C-14 is found to be as badly wrong and as grossly

over-inflated as this, how much reliance should we place on the

long-range dating for the early phases of the ice age? I only

ask this question. I don't know the answer" (Appraisal

of Anthropology Today, Chicago, 1953, p.78). On this see

also, Oakley, Man, Oct., 1951, p.142. The same authority

said subsequently (p.37), "C-14 dating seems to suggest

that the Upper Paleolithic developments came rather later than

we thought, and this only heightens the impression of a very

great speed-up in cultural development and differentiation."

A. L. Kroeber (p.39) strongly reinforced Clark's

words, underlining the change in view regarding both Old and

New World chronology. In the Illustrated London News, Sept.

14, 1935, Henry Frankfort suggests that "the earliest periods

of civilization in Mesopotamia are more closely related and extend

over a shorter period of time than is generally assumed."

pg.20

of 22 pg.20

of 22

One

is inevitably faced with the question of what had been happening in the

rest of the world that progress had been so fantastically slow, if it

really had occupied a time of some quarter to half a million years to

reach the lowest levels at Sialk. Such a long period with so little progress

is almost impossible to conceive of, especially when one realizes that

the art of the European caves attributed to Cro-Magnon Man was according

to Zeuner in the process of development some 72,000 years ago. (92)

In fact he admitted his own amazement at the slowness of development in

some cases. Thus in speaking of cultures during the Last Interglacial

he wrote: (93)

The interesting feature of this

evolution of the hand-ax industries is the small amount of change

observed, notwithstanding the huge time span covered. Judged

by the standards of, say the upper Paleolithic, the evolutionary

rates of the Crag "industries" and of the Abbevillian,

covering about 60 thousand years each, are small; but smaller

yet is that of the Acheulian which lasted through 300 thousand

years of which something like 200 thousand years appear to have

been occupied by the "middle stage." This conservatism

of the Acheulian is one of the most striking phenomena in the

chronology of the Paleolithic.

It is strange

indeed. Observe the sequence: for perhaps a quarter of a million

years intelligent men, to all intents and purposes apparently

much like ourselves in many respects, advanced their culture

scarcely at all. Then appeared a settlement in the Iranian highlands

near the traditional site of the landing of the Ark, which within

a period of perhaps 1,500 years developed into a culture in the

Mesopotamian plains, which in turn, within a thousand years,

gave rise to a series of high cultures scarcely paralleled until

comparatively modern times. (94) And finally, after this sudden burst of activity

lasting possibly a further 1,500 years or so, which witnessed

some of the finest cultural achievements in Babylonia, Egypt,

and the Indus Valley which the Middle East has ever seen, the

process was once more slowed up until many prosperous centres

decayed and disappeared, and much of India, Africa, and Europe

remained in a state of semi-barbarism till

92. Zeuner, F. E.. Dating the Past, Methuen,

1958, p.299, fig.81.

93. Ibid., pp.285 and 288.

94. We now have a new "twist" in the interpretation

of the evidence. The fact that there is no paleolithic phase

in the Middle East cannot, of course, be taken to mean that man

was civilized almost as soon as he appeared. This is not "evolutionary

thinking." So it must be assumed that the absence of the

earlier phase is due to the fact that it never was the Cradle

of Mankind -- never was a centre of hominid dispersion. The fact

that all lines of migration lead back here is simply discounted,

and the evidence is completely re-interpreted to support current

assumptions. See F. Clark Howell, "The Villafranchian and

Human Origins," Science, vol.130, 1959, p.833, col.

c.

pg.21

of 22 pg.21

of 22

well on toward Roman times, and

in some instances till much later The sequence takes the form, then, of

an unbelievably long time with almost no growth; a sudden spurt leading

within a very few centuries to a remarkably high culture; a gradual slowing

up, and decay, followed only much later by recovery of lost arts and by

development of new ones leading ultimately to the creation of our modern

world. What was the agency which operated for that short period of time

to so greatly accelerate the process of cultural development and produce

such remarkable results? And is the long prior period of slow "progress"

merely a figment of imaginative thinking resulting from a mistaken interpretation

of the facts? Is it possible to account for Paleolithic man in some other

way? Could he have been descended from rather than ancestral to the people

who so quickly created the cultures of the traditional Cradle of Civilization?

I think this is so. The sudden

rise of high culture in the Middle East is most readily accounted

for by reference to certain explicit statements in the early

chapters of Genesis, and to some reasonable implications based

upon them. And further, I am convinced that one can only account

for the extraordinary slowness of early cultural development

in Europe and elsewhere by reviewing those cultures in the light

of what we actually know from the history of primitive societies

since the White Man first made contact with them and began to

record his observations about them.

pg.

22 of 22 pg.

22 of 22  Copyright © 1988 Evelyn White. All rights

reserved

Previous Chapter Next

Chapter

Copyright © 1988 Evelyn White. All rights

reserved

Previous Chapter Next

Chapter

|