|

Abstract

Table of Contents

Part I

Part II

Part III

Part IV

Part V

Part VI

Part VII

|

Part IV: The Supposed Evolution of

the Human Skull

Chapter 2

Factors Influencing the Shape of

a Skull

For many years it has been observed

that food and environment may have a profound influence in modifying

bone structure. Recently it has been recognized that the human

skull is particularly sensitive in this respect. Many of the

more remarkable aspects of the skeletal remains of fossil man

may indeed be accounted for by such means, so that any series

arranged morphologically, without respect to age levels, is really

meaningless. Seen in this light it is often possible to view

a particular skull as owing its peculiarities not to any genetic

relationship with the lower anthropoid forms, but to a certain

community of habit and environment causing convergence and having

absolutely nothing whatever to do with derivation. The form may

be due to historical processes and have no palaeontological significance

whatever. This was Portmann's contention.

C. S. Coon also attributed Neanderthal's

form entirely to disease and to cold adaptation, with long trunk,

short limbs and arms, deep chest, etc., exactly like the Eskimo.

(13) Even man's

teeth can be profoundly modified by conditions of life. Singh

and Zingg noted that two of the more recent feral children found

in India (both of whom are now dead) had developed longer and

more pointed canines, presumably as a result of the eating of

raw meat without the use of any cutting utensils. (14) Another feral child, Clement

of Overdyke, had noticeably projecting teeth due to an uncooked

vegetarian diet. The "Wild Boy of Aveyron" had developed

canines conical in shape and very sharp, besides their being

longer than normal. Finally, Kaspar Hauser, kept captive in a

small dungeon for perhaps 12 or 14 years, had, in spite of being

given cooked food, developed a markedly depressed frontal region

as though "pressed down from above."

13. Coon, C. S., The Story of Man,

Knopf, New York, 1962, pp.40, 41.

14. Singh, J. A. L, and Zingg, Robert M., Wolf-Children and

Feral Man, Archon Books, Shoe String Press, Hamden, Connecticut,

1966, p.18.

pg

1 of 25 pg

1 of 25

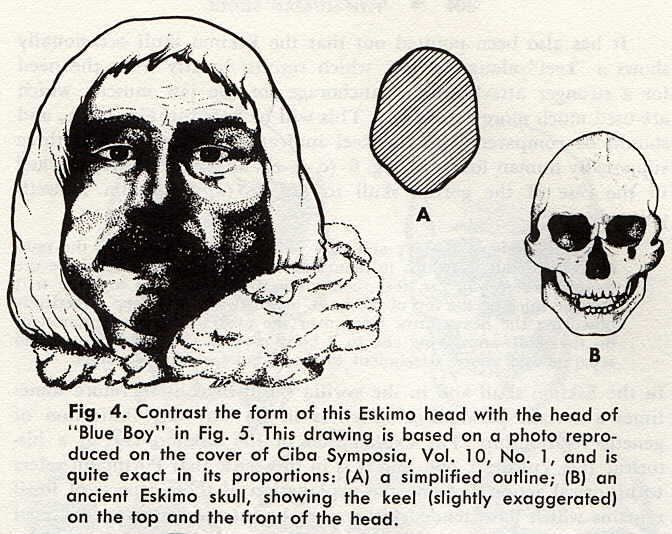

Of

the Australopithecines there are believed to have been two types,

A. africanus, and A. robustus. Robustus

is considered to be a later type, but less human. Africanus

had no saggital crest, or "keel," robustus had.

J. T. Robinson sees this, and stresses it is the result of diet,

and robustus was a plant eater. (15) The gorilla is also a plant eater, in whom the saggital

crest is enormous. Plant fibers can clearly be a tougher diet

than meat.

Robert B. Eckhardt, in an article

entitled "Population Genetics and Human Origins," observed

wisely: (16)

Indeed, are there any grounds

for assuming that morphological evidence alone makes it possible

to draw a valid distinction between the majority of these early

hominids and some ancestral hominid that may be concealed among

them? In view of the morphological variability among living hominoids,

I think not.

So neither stratigraphical

position nor morphological form is a safe base on which to establish

either age or relationship. With no possibility of applying the

test of actual breeding for assessment of relatedness, what really

is left but pure guesswork?

Although it seems little attention

was paid to his remarks at the time, Wilson D. Wallis some years

ago pointed out: (17)

The evidence of prehistoric

human remains does not in itself justify the inference of a common

ancestry with the apes. We base this conclusion on the fact,

if fact it be, that practically all the changes in man's structure

traceable through prehistoric remains are the result of changes

in food and habit.

The most notable changes are found

in the skull. Briefly the story of changes is to: a higher frontal

region, increased bregmatic height, smaller supercilliary ridges,

increased head width, less facial projection, decreased height

of orbits and a shifting of the transverse diameter downward

laterally, a more ovoid palate, smaller teeth, diminished relative

size of the third molar, shorter, wider and more ovoid mandible,

decrease in size of condyles, decrease in distance between condylar

and coronoid processes, and in general greater smoothness, less

prominent bony protuberances, less of the angularity and "savageness"

of appearance which characterizes the apes. This is evolution

in type, but the evolution is result rather than cause. . . .

Practically all of these features

of the skull are intimately linked together so that scarcely

can one change without the change being reflected in the others.

. . . Change is most marked in the region in which chewing

muscles function. . . . The adjacent walls of the skull

are flattened and forced inward as well as downward, producing

the elongation of the skull. The temporal muscles reach far up

on the skull,

15. Robinson, J. T., "The Origin and

Adaptive Radiation of the Australopithecines," in Evolution

and Hominization, edited by G. Kurth, Fischer, Stuttgart,

1962, pp.123-127.

16. Eckhardt, Robert B., "Population Genetics and Human

Origins," Scientific American, Jan., 1972, p.96.

17. Wallis, Wilson D., "The Structure of Prehistoric Man,"

in The Making of Man, Modern Library, New Yok, 1931, pp.69ff.

pg.2

of 25 pg.2

of 25

giving rise to a high temporal ridge:

they extend forward as well as backward, giving a more prominent

occipital region, and a more constricted forward region, resulting

on the forehead region of the skull in the elevation of the supercilliary

ridges and intervening glabellar region. Projecting brow ridges

are associated with stout temporal and masseter muscles and large

canines. . . . Constriction of outer margins of orbits

produces the high orbits which we find in apes, and to a less

marked degree in prehistoric human remains.

Even the nature

of the soil can have its effect in modifying bone structure.

Coon observed: "In my North Albanian series, I found that

the tribes of man living on food raised on granitic soil were

significantly smaller than those who walked over limestone."

(18) We really

have no idea at present, how extensively our conditions of life

modify our bone structure, nor the exact mechanisms involved.

So we simply do not know precisely why the typical fossil remains

of early man were so brutalized. Certainly it need have had absolutely

nothing to do with an animal ancestry.

With respect to the Eskimos, there

is some question as to whether their diet of frozen meat, cooked

or otherwise, is really as tough as might be supposed. Some authorities

claim that frozen meat has a consistency little tougher than

deeply frozen canned salmon, the freezing process having a kind

of tenderizing effect. It is also argued that the Eskimo habit

of chewing skins very thoroughly to soften them for clothing

is limited to the womenfolk, whose facial modification is less

pronounced than in the male population. (19)

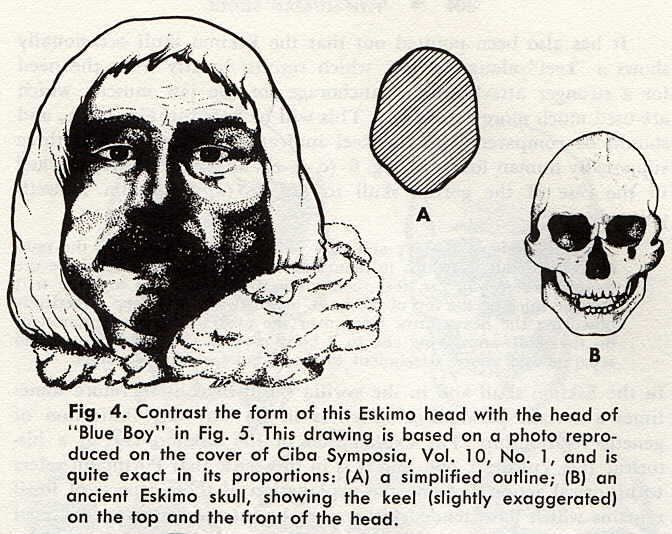

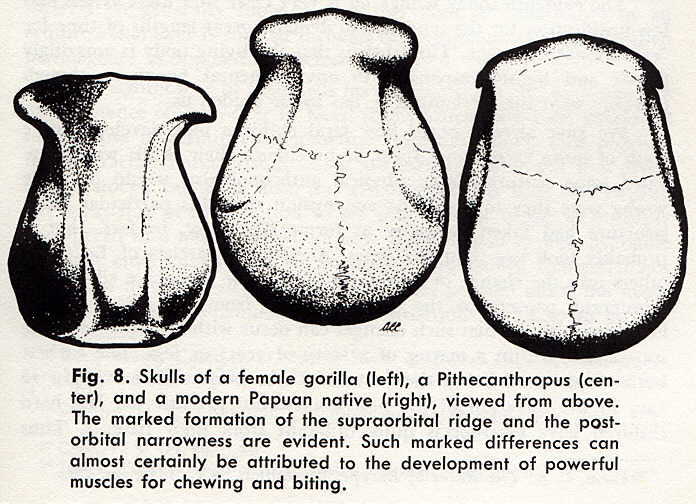

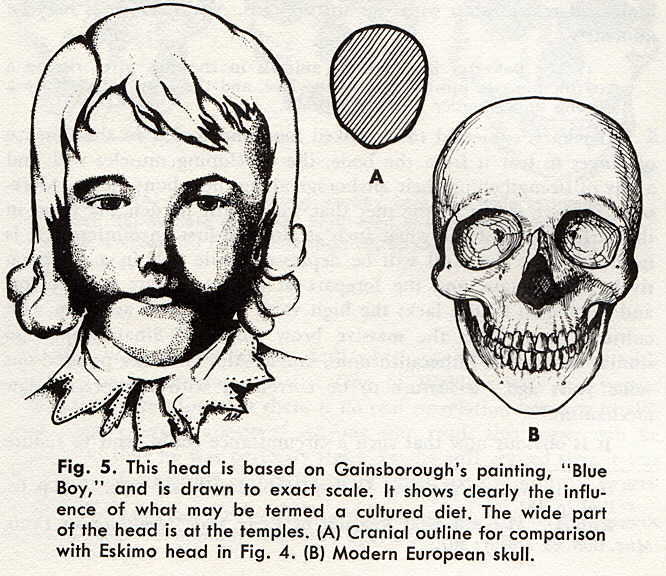

Fig. 4, however, shows a characteristic

Eskimo male face, with the skull form outlined to indicate that

the greatest width is at the jowls and not in the temple region.

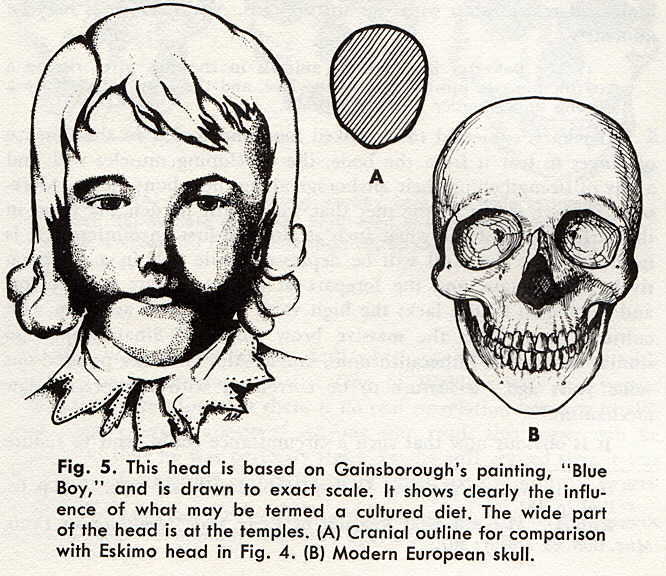

The head of Gainsborough's Blue Boy, in Fig. 5 however,

shows how a refined diet tends to produce a head form of another

kind with the greatest width in the temporal region. The drawing

of the Eskimo is taken from a magnificent photograph reproduced

on the front cover of Ciba Symposia of July, 1948. This

particular issue was devoted to aspects of Eskimo life, and the

articles were all contributed by Edwin H. Ackerknecht, who pointed

out that: (20)

The cheek bones and jaws of

the Eskimo are very massive, possibly under the influence of

the intense chewing he has to practice, which also results in

a tremendous development of the chewing muscles. Eskimo teeth

are often worn down to the gums, like animal teeth, from excessive

use.

18. Coon, C. S., ref.13, p.286.

19. Hooton, E. A., Up from the Ape, Macmillan, New York,

1935, p.405. He nevertheless admits that "there is something

to be said for the functional theory" (p.406).

20. Ackerknecht, Erwin H., "Eskimo History," Ciba

Symposia, vol.10, July, 1948, p.912.

pg.3

of 25 pg.3

of 25

pg.4

of 25 pg.4

of 25

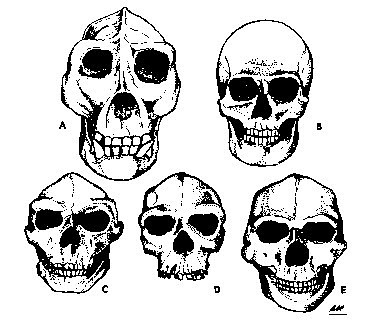

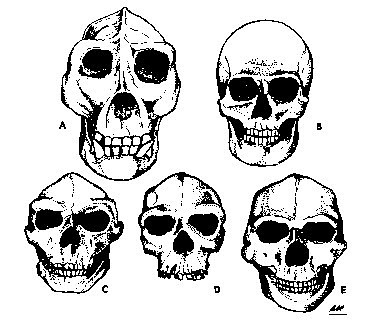

It

has also been pointed out that the Eskimo skull occasionally

shows a "keel" along the top, which results directly

from the need for a stronger attachment or anchorage for the

jaw muscles which are used much more extensively. This will be

noted in Fig. 4 (b), and should be compared with the keel indicated

in the skulls of three supposedly human fossils in Fig. 6 (c,

d, e). It is very clearly marked in the case of the gorilla skull

in Fig. 6 (a). William Howells pointed out: (21)

Gorillas have a heavy and very

powerful lower jaw, and the muscles which shut it (which in man

make a thin layer on and above the temple, where you can feel

them when you chew) are so large that they lie thick on the top

of the head, about two inches deep, practically obscuring the

heavy brow ridge over the eyes which is so prominent on the skull,

and giving rise to a bony crest in the middle merely to separate

and afford attachment to the muscles of the two sides.

In the Eskimo

skull and in the gorilla skull, there is therefore sometimes

a certain parallelism which is in no way any indication of genetic

relationship. The explanation of the Eskimo keel is an historical

(i.e., cultural) one, and it is in this sense that Portmann refers

to historical action as being the explanation of those aspects

of fossil remains which have tended hitherto to be interpreted

as evidence of biological relationship with the anthropoids.

Again, Howells may be quoted: (22)

The powerful jaw of these animals

in chewing, gives rise to a terrific pressure upward against

the face, and the brow ridges make a strong upper border which

absorbs it.

If man is subjected

to uncooked food and forced in the absence of knives to tear

it from the bone, the developing muscles will find a way of strengthening

their anchorage along these bony ridges. Moreover, if there is

not in the diet that which will harden the bone in the earlier

years of life when such strains are first encountered, it is

inevitable that the skull will be depressed while still in a

comparatively plastic state, and the forepart of the brain case

will be low and sloping so that it lacks the high vault we tend

to associate with cultured man. Thus the massive brow ridges

of Sinanthropus, so similar to those of Pithecanthropus, are,

as Ales Hrdlicka pointed out some years ago, "a feature

to be correlated with a powerful jaw mechanism." (23)

It is obvious now that such a circumstance

could tend to reduce

21. Howells, William, Mankind So Far,

Doubleday Doran, New York, 1945, p.68.

22. Ibid., p.131.

23. Hrdlicka, Ales, "Skeletal Remains of Early Man,"

Smithsonian Institute, Miscellaneous Collection, vol.83,

1930, p.367.

pg.5

of 25 pg.5

of 25

Fig. 6. (A) Gorilla, showing marked keel and wide zygomatic

arch. (B) Modern Man with high vault and widest dimension at

the temples. {C) Pithecanthropus. (D} Rhodesian Man. (E) Sinanthropus.

the high vault of the human skull which we

usually associate with man's superior mental capacity. One of

Weidenreich's last papers was intended to show that there is

no real correlation between intelligence and cranial capacity.

(24) Anyone who

reads this paper will be convinced that he was perfectly right.

Yet he still argued that it was man's greatly enlarged cranial

capacity which gave to him his superiority

24. Weidenreich, Franz, "The Human Brain

in the Light of its Phylogenetic Development," Scientific

Monthly, Aug. 1948, pp.103f.

pg.6

of 25 pg.6

of 25

over the other primates.

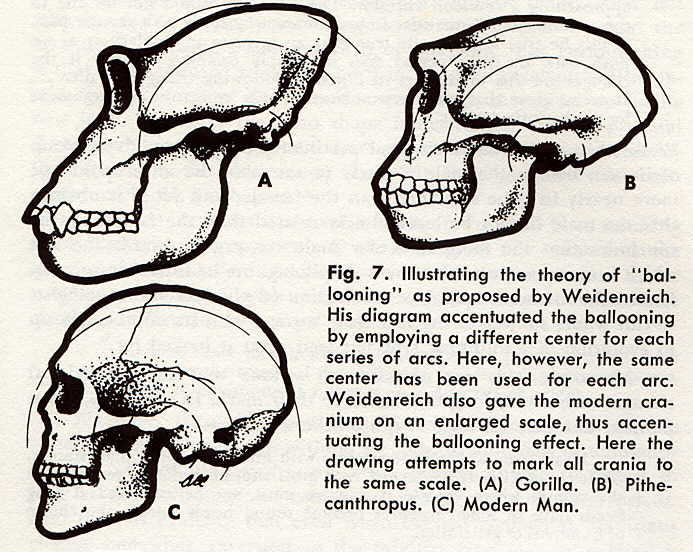

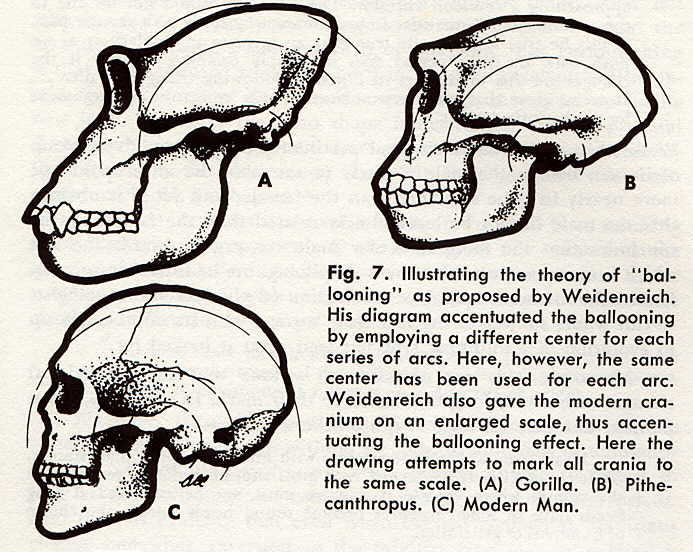

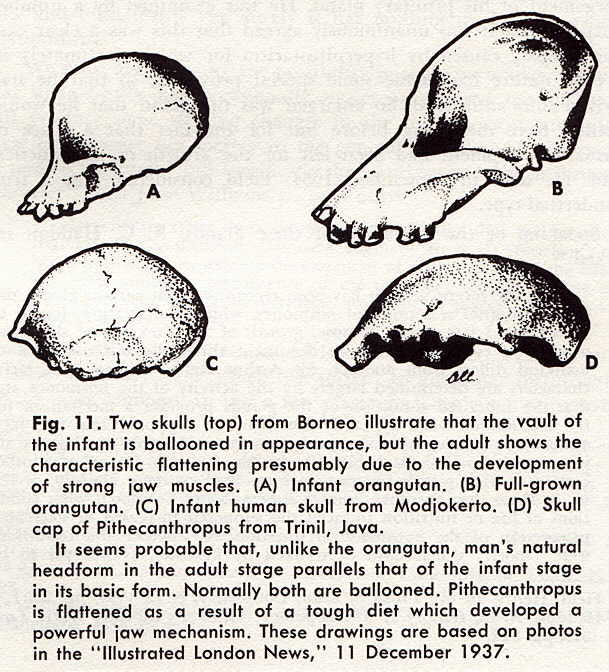

Weidenreich was of the opinion that for some unknown reason,

man's brain suddenly began to increase in size. This had the

effect of "ballooning" the skull on an arc centred

approximately at the junction of the lower jaw and the skull

proper, as illustrated in Fig. 7 (c) . Not everyone has taken

this theory too seriously. Howells referred to it rather contemptuously

as "a feeble argument with no proof behind it." (25) He offered no alternative.

But Weidenreich's argument is based

essentially on the fact that if we rather arbitrarily draft a

series of skulls, in this case the gorilla, Pithecanthropus,

and modern man, and in a side view impose upon them as indicated

in Fig. 7 a series of arcs centred approximately at the ear,

we have a series of forms with increased ballooning from the

true animal to the true man. As indicated in Fig. 4 however,

Weidenreich's original drawing was hardly fair, since he exaggerated

the effect by using a different scale for the various skulls.

(26) Moreover,

the gorilla and modern man are contemporaries, and the series

does not therefore represent anything historically factual as

a series.

There is another explanation of

such a series however, in which we merely assume that the first

true man had a high vault, but that the circumstances of his

early history were such as to deprive him of some of the essentials

of culture thus forcing him to adopt the use of raw meat, which

in time greatly developed the jaw muscles and thus "deflated"

the high vault with which his ancestors had been endowed. This

is exactly the reverse of Weidenreich's theory, but it has this

at least in its favour, that there is historical evidence to

support it. The evidence of history, as observed in the actual

time sequence of many of the fossils which Weidenreich was forced

to arrange out of order, is manifestly against his theory. The

objection to our alternative, of course, is that we must assume

that man was equipped with a high vault and presumably a large

brain to go with it, from the very first.

It could also be argued that if

at first, man's genetic heritage provided him with the means

to grow a high vault, then when this could not develop, the mechanism

compensated itself by building a much thicker vault instead.

It might happen therefore that the high vault with normal bone

thickness is more or less exactly represented by a low vault

with a much thicker bone shell. The weight of both forms of skull

would presumably be quite similar. Some of the early skulls show

this thickening.

25. Howells, William, ref.31, p.76.

26. Weidenreich, Franz, Apes, Giants and Man, University

of Chicago Press, Chicago, 1946, fig.36.

pg.7

of 25 pg.7

of 25

Weidenreich

elaborated his ballooning theory in his book Apes, Giants

and Man. He assumed that man started with a powerful jaw

mechanism. Then he explains what he thinks must have happened:

(27)

The reduction of the jaws went

hand in hand with a reduction of the chewing and cervical muscles.

The space required for the attachment of these muscles to the

skull surface consequently became smaller, and so did the power

of the whole chewing apparatus. The superstructures which reinforce

a primitive skull in the forms of crests and ridges diminished

accordingly. . . .

Exaggeratedly expressed, the evolution

of the human brain case proceeds like the inflation of a balloon;

and it looks as though the enlargement of its content the brain,

was the driving factor. . . . The transverse axis around

which the skull is bent runs approximately through the jaw points.

. . . All the smaller structural alterations of the human

skull are correlated with and dependent upon each other and the

extent to which they are governed by the trend of the skull transformation

as a whole. All fossil human forms, from the more ancient morphological

stage to the most advanced ones, show that the state of the minutest

structure of the cranial bones corresponds in some way to that

of the entire skull form and thereby proves that all forms must

once have passed through the same principal phases. . . ,

Now reversing

the pattern we can view the process quite differently. Let us

assume, for the sake of argument, that early man was subsequently

forced to eat tough food, after the initial family had multiplied

and wandered apart; and that this food lacked that which would

harden the skull in its formative period of development: then

the strengthening of the chewing and cervical muscles would go

hand in hand with the building of a superstructure of bone to

provide the necessary anchorage in the form of crests as well

as ridges in the front, at the rear, and on the top of the skull,

but the skull itself would remain pliable enough that it would

undergo considerable distortion.

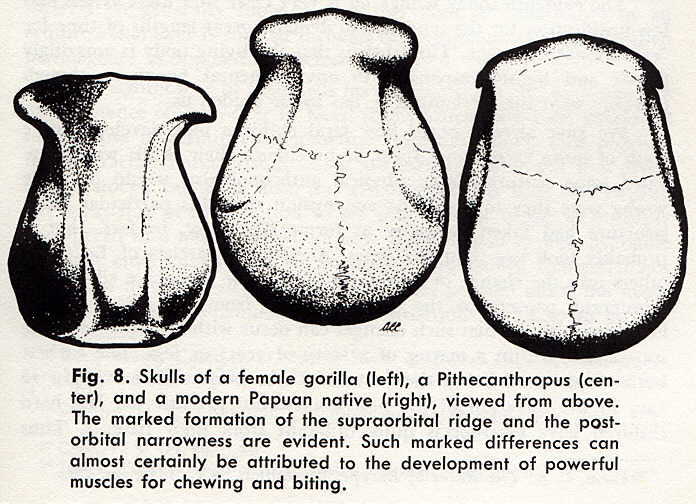

The "keel" which is so

noticeable in the case of the gorilla, naturally tended to appear

in early man because the muscles pulled the sides of the skull

in, under the increased tension. This is indicated in Fig. 8.

When the jaw was used for cracking

bones, etc., the chief point of stress would regularly occur

at the chin, since the clamping action between the teeth would

normally be one-sided. This again led to a certain degree of

compensatory thickening. But unlike the apes, man is a talking

creature and makes much more use of his tongue. There is reason

to believe that the reinforcement of man's chin takes the form

of a bony ridge outwards rather than inwards, on this account,

and this gives the prominence which is characteristic of the

human jaw. The apes and other anthropoids on the other hand have

the

27. Ibid, ref.26, p.33.

pg.8

of 25 pg.8

of 25

reinforcement in the

form of a ledge which reaches inward instead, and this is known

as the simian shelf. In some fossils of early man there is some

evidence of a simian shelf, and presumably this is a reinforcement

in addition to that which is normal for man's chin, by way of

compensation for the added load placed upon the structure at

this point. Tugging at flesh in the absence of satisfactory "cutlery,"

or maybe just bad table manners, contributed quite possibly to

the alveolar prognathism which is often found in these early

remains. The increasing muscle development which rose up under

the zygomatic arch naturally forced the latter outwards and required

a stronger form.

It is quite likely therefore that

the functioning of the jaw mechanism determines whether the skull

will be depressed or not. The fossil human forms then show clearly

that the entire series has been affected to a large degree by

the same depressive and compressive forces. Thus if early man

were to have been utterly deprived of culture it seems quite

certain his fossil remains would have revealed an extreme primitiveness

which might easily be misinterpreted as evidence of a recent

emergence from some anthropoid stock. Yet in point of fact it

could happen that individuals might become degenerate at any

period in history and leave behind them a cemetery of the most

deceptive fossil remains. Humphrey Johnson remarked in this direction

(28)

It seems likely that in very

early times the human form possessed a high degree of plasticity

which it has since lost, and that from time to time such exaggerations

of certain racial characters, probably brought about by an unfavorable

environment, have occurred. In the Pekin-Java branch of the human

family, the exaggeration of the ape-like traits has occurred

to a very high degree: it later took place, so it would seem,

though not quite so pronounced in Neanderthal Man, and has occurred

again though to a far lesser extent in the aborigines of Australia.

Some of the low features of the

Australians may, as Prof. Haddon thinks, be due to racial senility

and thus the resemblance to Neanderthal man may be regarded as

secondary or convergent. By a wider application of this principle

we may consider that "convergence" has played a part

in bringing about the resemblances of paleoanthropic men to the

anthropoid apes.

And quoting

Wallis once more: (29)

If the above interpretations

are correct it follows that a return to the conditions of diet

and of life which characterized prehistoric man would be followed

by a return to his physical type. Yet if there were this transition

to a type more simian we could not say that we were

28. Johnson, Humphrey, The Bible and the

Early History of Mankind, Burns and Oates, London, 1947,

p.89.

29. Wallis, Wilson D., ref. 17, pp.72ff.

pg.9

of 25 pg.9

of 25

pg.10

of 25 pg.10

of 25

approaching a common ancestor. The similarity

would not be due to the transmission of qualities from a common

ancestor of a remote past. If this be true it is equally true

that an increase in similarities as we push back the time period

does not imply common ancestry if the changes are due to changes

in function, following changes in diet. . . . It seems

clear that mere resemblance cannot constitute an argument for

phylogentic descent.

Wallis then

points out with great pertinence that in any given group of human

beings, the male is likely to resemble the anthropoid ape more

nearly in bone structure than the female; and yet it is obvious

that the male cannot be more closely related than the female.

So he concludes that the more muscular male converges towards

the ape which is more muscular than man simply because he is

more muscular. He attributes the comparative inattention of physical

anthropologists to this whole subject to the fact that "an

age with its mind made up to evolution of a unilinear type has

seen what it looked for."

Moreover, it is not necessary to

assume that such functional changes take a very long time to

leave their mark. In fact, C. S. Coon pointed out that the case

is quite otherwise: (30)

Head form, although it changes

with much less speed than stature, for it is not directly concerned

with gross size, nevertheless responds to the stimuli which control

it and we must not be surprised if long heads have in some instances

become round heads during the course of hundreds of generation.

The evidence

today is making it very clear that there is less and less justification

for the tendency to demand great lengths of time for "evolutionary"

change. The truth is that the living body is amazingly plastic

and highly responsive to environmental pressures, though precisely

what the mechanism is, has so far eluded us.

We have already noted how feral

children may develop canine teeth of quite exceptional form.

If by chance their skulls were excavated some centuries later,

physical anthropologists would be quite wrong were they to make

the assumption that this particular tooth structure had taken

centuries to form. We know, in fact, that it probably took less

than ten years. And the researches of Boas and others into the

change of head-form among the successive siblings of the United

States from an area of longheadedness, shows that such changes

can occur with remarkable rapidity -- again, within a matter

of a score of years or less. The earliest born children resemble

the parents. Later born children begin to vary in the direction

of the new home-country, until the last born children have head-forms

quite different from their parents. Thus

30. Coon, C. S., The Races of Europe,

Macmillan, New York, 1939, pp.28f.

pg.11

of 25 pg.11

of 25

Boas (31) showed that the influence of environment makes itself

felt with increasing intensity according to the time elapsed

between the arrival of the parents and the birth of the child.

The curious thing is that those children who were born in the

old homeland still maintain the head-form of the parents, even

though they grow up in the new land. Evidently the head shape

is determined during prenatal development so that if prenatal

development occurs in the old country the influence of the new

country is not felt. Boas' work has since been confirmed by H.

L. Shapiro (32)

Coon also mentions that modifications

in the skull form resulting from dietary habits, particularly

the eating of raw meat and the absence of bone hardening substances

in childhood, may occur, under sub-Arctic conditions, with remarkable

rapidity. He notes that these changes are functional changes

and he concluded: (33)

Metrical and morphological differences

in physical type which appear during the course of the millennia

may imply, in some instances, a response to environment rather

than a diversity of origin.

We have, then,

a mechanism that might account for all the variant forms of fossil

man without recourse to hundreds of thousands of years of evolutionary

history. Such changes appear to persist so long as the environmental

conditions which provoked them persist. And there is evidence

that even when the environmental conditions change somewhat,

reversion to the original type may be delayed a little. It is

generally thought that this kind of inheritance of an acquired

character is effected through the cytoplasm, through so-called

plasmagenes as opposed to nuclear genes.

The significance of such facts

here is that there may be a measure of persistence or carry-over

in facial forms which have been developed in response to certain

environmental pressures, which thus provides us with racial characteristics

which are then traceable not to a diversity of stocks, but to

an historical circumstance. It does not require any great feat

of imagination to see that as man began to multiply and spread

into new areas where new types of food became available and new

environments led to modified living habits, changes might take

place in his physical form. Wood Jones (34) pointed out the needs created by any well-defined

ecological situation are likely to be met

31. Boas, Franz, Changes in Bodily Form

of Descendants of Immigrants, Government Printing Office,

Washington, 1911; reprint, Columbia University Press New York,

1912.

32. Shapiro, H. L., Migration and Environment, Oxford

University Press, 1939.

33. Coon, C. S., ref.30, p.29.

34. Jones, Wood, Trends of Life, Arnold, London, 1953,

p.76.

pg.12

of 25 pg.12

of 25

by all living things

subjected to them by directive responses of a similar kind. The

pliability of living forms is great. Ralph Linton put it this

way: (35)

If we are correct in our belief

that all existing men belong to a single species, early man must

have been a generalized form with potentialities for evolving

into all the varieties which we know at present. It further seems

probable that this generalized form spread widely and rapidly

and that within a few thousand years of its appearance small

bands of individuals of this type were scattered over most of

the Old World. These bands would find themselves in many different

environments, and the physical peculiarities which were advantageous

in one of these might be of no importance or actually deleterious

in another. Moreover, due to the relative isolation of these

bands and their habit of inbreeding, any mutation which was favorable

or at least not injurious under the particular circumstances

would have the best possible chance of spreading to all the members

of the group. It seems quite possible to account for the known

variations in our species on this basis without invoking the

theory of a small number of originally distinct varieties.

Or we may quote

Franz Boas in the same connection: (36)

If we bring two organically

different individuals into the same environment they may, therefore,

become alike in their functional responses and we may gain the

impression of a functional likeness of distinct anatomical forms

that is due to environment, not to heredity.

It is abundantly

clear by now, therefore, that we are dealing here with a fact

which is very widely recognized. Yet, in spite of this, it is

seldom referred to when the search for the missing link seems

to be getting warm.

When Broom found a number of items,

teeth, parts of the jaw, and parts of the cranium, etc., of the

specimen subsequently named Australopithecus transvaalensis,

the matter was reported in the Illustrated London News

with pictures of the then most recent additions to the finds,

and a reconstruction of the "head." The significant

factors in this find, according to Broom, lie in the presence

of a clearly ape-like form of the head and the obviously humanoid

aspect of certain of the teeth. No one would doubt, we are told,

seeing the skull, that it was the skull of a variety of chimpanzee

or an anthropoid ape. But looking at the teeth apart from the

rest of the skull he said: (37)

If casts of these teeth had

been sent to all the anatomists of the world, probably 95% would

have certified that they are human. The size, the arrangement

and the wearing are all human characters. . . .

We need not at present discuss

the exact position of Australopithecus, but we can without hesitation

state that here we have an anthropoid ape with a brain capacity

probably between 450 and 650 cc., and

35. Linton, Ralph, The Study of Man,

Appleton Century, New York, 1936, p.26.

36. Boas, Franz, ref.31, p.133.

37. Broom, Illustrated London News, May 14,1938.

pg.13

of 25 pg.13

of 25

thus definitely an ape, but which has

teeth which are almost typically human. The incisors, canines,

premolars, and first molars are hardly to be distinguished from

human teeth. The second and third molar are considerably larger

than in man, but very similar to human teeth in structure.

It seems to me that these human

characters are much more likely to indicate affinity with man,

than that such characters have been twice independently evolved.

But in the same

paper there had already been reported by W. P. Pycraft (38) some three years earlier,

a remarkable series of finds in South America of three skulls

belonging to quite unrelated animals in which a particular bone

structure on the lower jaw had assumed substantially the same

striking form entirely in response to diet and having nothing

to do with common descent. These three skulls belonged to marsupials

and at the time were described by Sir Arthur Smith Woodward as

perhaps the most remarkable "mimics" (as he called

them) hither discovered.

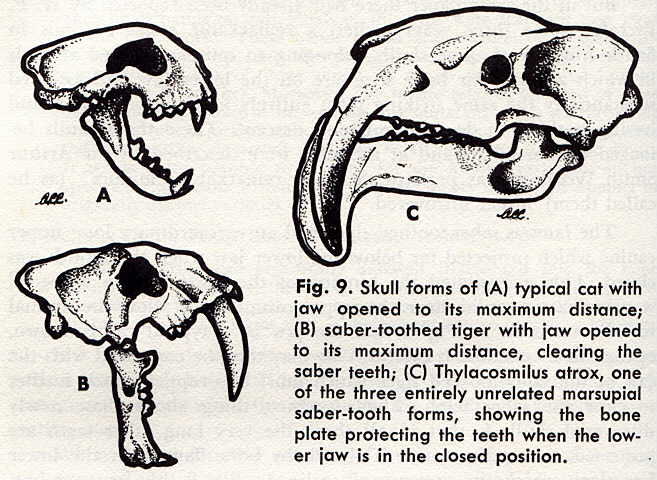

The famous saber-toothed tiger

had an extraordinary long upper canine which projected far below

the lower jaw when the mouth was closed. This necessitated the

hinging of the lower jaw in a special way so that it would clear

the upper canines and allow the animal to seize its prey. In

Fig. 9 first the jaw of a typical cat is shown, opened to its

maximum extent. This may then be compared with the jaw of the

saber-toothed tiger which must be dropped much further to clear

the saber teeth. The surprising thing about these newly discovered

skulls is that in all three the very long saber teeth are protected,

when the mouth is closed, by bone flanges on the lower jaw along

which the upper canines lie. In Fig. 9 this structure can be

clearly seen. The other two skulls show a parallel development,

although the photographs of them available to the public do not

show quite as clearly the precise form of the protective flange;

but there is no doubt about the parallelism in structure. The

important thing is, as Pycraft observed, that these flanges illustrate

"the molding effects of particular modes of life which more

commonly than is generally realized, start with the choice

of food" [emphasis mine].

Perhaps it is not so remarkable

after all to find Australopithecine with teeth so strikingly

like human teeth.

We may quote Wood Jones once more: (39)

All these needs are met by the

development of structures directed towards their satisfaction.

It seems therefore certain that structures developed for the

satisfaction of these common needs may bear a considerable likeness

to each other, although the animals manifesting them

38. Pycraft, W. P., Illustrated London

News, Feb.16, 1935.

39. Jones, Wood, ref.34, p.71.

pg.14

of 25 pg.14

of 25

may be utterly unrelated by kinship

or descent. Since so many basic needs are common to all animals

and these functional needs are satisfied by the development of

appropriate structures, it is to be expected that a common ground

plan of parts and organs might be detected as underlying the

very varied superstructures of large groups of animals.

Yet the slightest

resemblance between an early human fossil and the skull or other

parts of some lower primate is at once taken to mean genetic

affinity, and it is seized upon as proof in part of the general

theory that man has been derived by some such steps from an animal

ancestor. Against such hasty assumptions we must now be much

more ready to examine the parallelisms to see whether they may

not be explained satisfactorily on other grounds. In this connection

it is well to underscore the words of LeGros Clark, who over

twenty years ago pointed out: (40)

In the evaluation of genetic

affinities anatomical differences are more important as negative

evidence than anatomical resemblances are as positive evidence.

It becomes apparent that if this thesis is carried

40. Clark, LeGros, Early Forerunners of

Man, 1934, as quoted by Rendle Short in Transactions of

the Victoria Institute, London, vol.67, 1935, p.255.

pg.15

of 25 pg.15

of 25

to a logical conclusion it will necessarily

demand a much greater scope for the phenomenon of parallelism

or convergence in evolution, than has usually been conceded by

evolutionists. The fact is that the minute and detailed researches

which have been carried out by comparative anatomists in recent

years have made certain that parallelisms in evolutionary development

have been proceeding on a large scale and it is no longer to

be regarded as an incidental curiosity which has occurred sporadically

in the course of evolution. Indeed, it is hardly possible for

those who are not comparative anatomists to realize the fundamental

part which this phenomenon has played in the evolutionary process.

The influence

of environmental pressures in modifying the structure of an organism

is so common in fact, that it would almost seem as though convergence

of unlike forms until they are alike is more frequent in nature

than the reverse -- divergence of like forms until they are unlike.

And yet the latter is the fundamental requirement of evolution.

Although too little attention seems

to have been paid to his work, Leo S. Berg, in a book devoted

to this question, argued: (41)

Convergence and not divergence

is the rule, not the exception. This appears to be all pervasive,

both among plants and animals, both present, recent, and extinct.

We do not find a few simple forms giving rise to a great variety;

we find a great variety assuming similarities that have in the

past led, or misled all naturalists into thinking that the opposite

was taking place. . . .

In studying extinct forms of life,

it is most unusual to find a common ancestor for any series of

living animals or plants living today. The common ancestor almost

invariably turns out to be in some respect or other more complicated

than its alleged descendants.

It ought not

to surprise us therefore to find anthropoid forms appearing in

varying degree among true Homo sapiens.

With respect to the influences

of temperature on body form and colour, a remarkable case is

given by A. F. Shull who reported some experiments in which pupae

of certain butterflies were subjected to abnormally low temperatures.

(42) There emerged

from them insects having a pattern and colours resembling a more

northerly variety of the same species, and there was reason to

believe that the two varieties were genetically similar but in

the different environments in which they occurred naturally,

they had appeared as different varieties. When transported into

a similar environment, the variation was reduced markedly. In

a lesser degree there is some evidence that human beings may

respond to environmental pressures to become alike in certain

respects. Cold climates tend to stimulate a lengthening of the

41. Berg, Leo S., Nomogenesis, or Evolution

Determined by Law, English translation, Constable, London,

1926, p.174.

42. Shull, A. F., Evolution, McGraw Hill, New York, 1936,

p.249.

pg.16

of 25 pg.16

of 25

nose, perhaps to create

a longer passage of warming for the air inhaled, before it reaches

the lungs. Limbs may be shortened slightly, for the same reason,

to reduce radiation of heat from the body. In very hot climates

the air passage to the lungs may be shortened by a corresponding

shortening or flattening of the nasal passages. (43) And there are other even

more striking bodily modifications in response to heat and high

humidity that lead to the Nilotic Negro type and the Pygmy type,

in both of which the body has increased its surface area (for

radiation purposes) relative to the body mass, in one instance

by assuming a very long thin form, and in the other by reducing

the total size. Both the Nilotic Negroes and the Pygmies of the

Ituri forest in Africa, share a similar environment of high temperature

and high humidity. (44)

Thomas Gladwin points out that

animals are modified in the same way as human beings in environments

of this extreme kind. When F. B. Sumner reared white mice at

20 degrees and 30 degrees C., he found that at the higher temperatures

they developed longer bodies, tails, ears, and hind feet. (45) Yet, surely it has nothing

to do with genetic relationships.

We must also consider the possibility

in some particular instances that some fossils may occasionally

represent diseased types. Disease will produce some striking

changes in the human form, and often these changes are not merely

in the general direction of what must be termed "ugliness,"

but specifically they tend towards the anthropoid character.

Thus Jesse Williams pointed out: (46)

Degenerate types show characteristic

markings that are known as stigmata of degeneration. Common stigmata

are: (1) receding forehead, indicating incomplete development

of frontal lobes of the brain; (2) prognathism, a prominence

of the maxillae. (3) the canine ear; (4) prominent supercilliary

ridges; (5) nipples placed too high and supernumerary nipples.

Among the disorders

which commonly operate to effect a modification of bone structure,

those which are related to glandular disturbances are the most

common. In fact a few years ago there was a remarkable

43. On these points see further: "Stature

and Geography," Scientific American, Apr. 1954, p.46.

Montagu, Ashley, "A Consideration of the Concept of Race,"

in Cold Spring Harbor Symposia on Quantitative Physiology,

vol.15, 1950, p.325ff., and "Physical Characteristics

of the American Negro, Scientific Monthly, July, 1943,

pp.58ff.

44. Gladwin, Thomas, "Climate and Anthropology," American

Anthropological Institute, vol.49, Oct.-Dec., 1947, p.607ff.

45. Klotz, J. W., Genes, Genesis and Evolution, Concordia,

St. Louis, 1955, p.28.

46. Williams, Jesse, Textbook of Anatomy and Physiology, 5th

edition, Saunders, Philadelphia, 1935, fn. p.49.

pg.17

of 25 pg.17

of 25

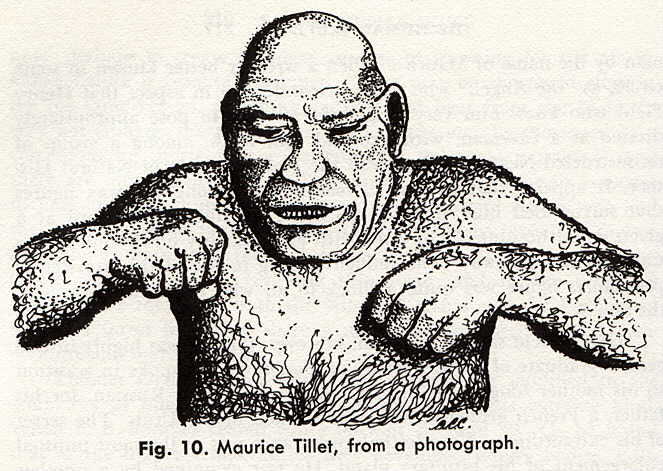

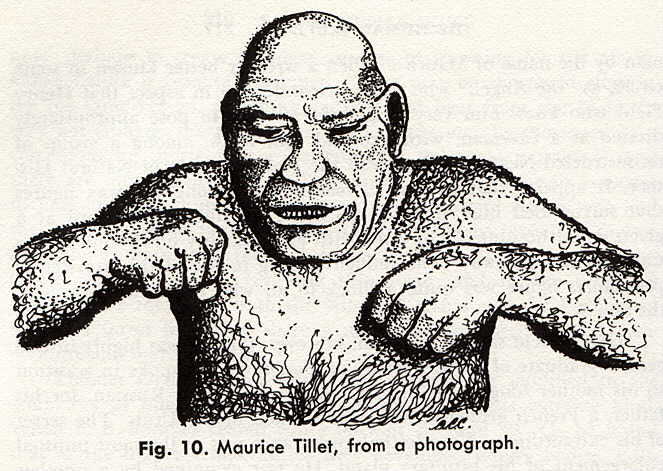

man by the name of Maurice

Tillet, a wrestler better known in some circles as "the

Angel," who was so Neanderthal in aspect that Henry Field

who knew him very well, induced him to pose appropriately dressed

as a caveman, with ax and loin cloth, among a group of reconstructed

Neanderthal men in the Field Museum of Natural History. It appears

that he was so readily lost among the wax figures that surrounded

him, that he could not be singled out until at a given signal

he plunged forward with an unearthly howl while Pathe Cameras

ground away! The sudden coming to life of this apparently prehistoric

figure was quite a shock to all who subsequently viewed the film.

(47)

Henry Field says of this man, however,

that he was highly intelligent, a graduate of the University

of Toulouse, and spoke in addition to his mother tongue, Spanish,

English, and a little Russian, for his father, a French geologist,

had once worked in the Urals. The secret of his extraordinary

Neanderthal appearance was in the most unusual enlargement of

his pituitary gland. He was examined by a number of experts and

it was unanimously agreed that this was a clear case of acromegaly

caused by hyperpituitarism for which, fortunately in his case,

nature had made some special provision, so that he had survived

into adulthood. So enlarged was the gland that he would certainly

have died long before but for the fact that a space of unusual

development had been left for the growth of this ductless gland.

He died in September, 1954. Field considered him a true Neanderthal

type.

Speaking of the operation of these

glands, A. C. Haddon remarked: (48)

During recent years it has been

recognized that certain glands discharge internal secretions,

or hormones, which alter stature, length of limb, size of jaw,

shape of nose, growth of hair, texture of skin, and other characters

which are in the main those wherein one race of mankind differs

from another. Sir Arthur Keith suggests that racial characters

are determined largely by the activity of the hormones and that

the inherited condition of the glands provides a mechanism for

the fixation of racial types. It must not be supposed that the

facts adduced by Keith imply that such groups as Mongols or Negroes

are in any sense pathological, but merely that for some reason

or another certain ductless glands function in some respects

more actively, or less so, in these than in other groups. It

remains to be shown what conditions of life or nutrition induced

the supposed increased or decreased production of the hormones

in question, or whether the conditions were "sports"

which have been fixed by heredity. It has yet to be proved that

these hormones are alone responsible for all racial differentiation,

though they may well be contributing factors.

47. Field, Henry, In the Track of Man,

Doubleday, New York, 1953 pp.230f.

48. Haddon, A. C., History of Anthropology, Thinker's

Library Watts, London, 1949, pp.34f.

pg.18

of 25 pg.18

of 25

pg.19

of 25 pg.19

of 25

Since Neanderthal Man is usually considered as a "race,"

the possibility that racial characteristics of this kind could

in fact be the result of pituitary or other glandular disturbance,

is greatly strengthened by the case of Maurice Tillet. We thus

have, in addition to the influences of diet and eating habits,

the possible influences of glandular abnormality. It is conceivable

that the giantism which has been found to characterize some early

fossils of man, could be traced to the same factor. In this case

history as opposed to genetics, in Portmann's sense of the terms,

would possibly explain Gigantopithecus and Meganthropus, and

so forth, as well as the grossness of some European forms; and

any attempt to fit them into a genetic series would be a waste

of time.

But it is not only the pituitary

gland which can so modify the human form. Sir Arthur Keith, in

another work on this subject, pointed out that the characteristics

used as physical criteria by etymologists for distinguishing

different racial stocks are affected by several glands in the

body. Of these the chief are the pituitary and pineal glands,

but the thyroid gland in the throat and the adrenal glands in

the kidneys are also of importance. Abnormal growth of the pituitary

leads as we have seen to enlargement of the chin, nose, and brow.

These features to some extent are common to almost all so-called

cavemen. Keith put it this way: (49)

We are justified in regarding

the pituitary as one of the principal pinions in the machinery

which regulates the growth of the human body and is directly

concerned in determining . . . the tendency to strong eyebrow

ridges.

Such brow ridges

are among the features of fossil man which have tended, in the

public mind, to give the most ape-like cast to the face. It is

curious that such ridges are more marked among Europeans, i.e.,

the White Man, than among some of the other races. In fact Charles

Darwin and Thomas Huxley showed quite marked brow-ridge formation,

and it has been suggested by some physiologists that such prominences

are evidence of great energy. (50) This could speak well for men of prehistoric times.

Speaking of the thyroid gland,

Robert Speer pointed out: (51)

Many characteristics which have

hitherto been regarded as hereditary

49. Quoted by Sir John A. Thompson, in The

Outline of Science, vol.4, Putnam, New York, 1922, p.1097.

50. Mottram, V. H., The Physical Basis of Personality, Penguin

Books, Hammondsworth, Middlesex, England, 1949, p.79.

51. Speer, Robert, Of One Blood, Friendship House, New

York, 1924, p.11.

pg.20

of 25 pg.20

of 25

or racial, may be due to environmental

causes, it is probable, for example, that stature and longheadedness

may be caused by higher or lower activity of the thyroid gland,

and that this may in turn be influenced by food, particularly

iodine.

Among animals,

the changes due to food, temperature, etc., can be quite remarkable.

George Dorsey has given an interesting list of some of the changes

which can be induced. He wrote, (52)

For example, tadpoles fed on

thymus gland become big dark tadpoles -- but never develop into

frogs; if fed adrenal gland, they become very light in color.

Larvae of bees fed royal jelly become queens; on bee bread, non-fertile

females or workers. Canaries fed on sweet red pepper become red

in color. The germ as the "bearer of heredity" is meaningless

or monstrous apart from its usual environment. . . .

The hormones actually known are

definite and specifically acting indispensable chemical products

which modify development and growth of other organs, especially

during embryonic life, and the entire metabolism, including that

of the nervous system, during adult life. Then, too, there is

a collective operation of the endocrines as yet not definitely

known, but summarized by Barker as follows:

"More and more we are forced

to realize that the general form and the external appearance

of the human body depends to a large extent upon their functioning.

Our stature, the kinds of faces we have, the length of our arms

and legs, the shape of the pelvis, the color and consistency

of our integument, the quantity and regional location of our

fat, the amount and distribution of hair on our bodies, the tonicity

of our muscles, the sound of the voice, and size of the larynx,

the emotions to which our 'exterieur' gives expressio n --all

are to a certain extent conditioned by the productivity of our

hormonopoietic glands. We are, in a sense, the beneficiaries

and the victims of the chemical correlations of our endocrine

organs."

Keith pointed

out that a poorly developed thyroid leads to stunted growth,

to undeveloped nose and hair, and to a flat face. These are characteristic

of some of the so-called Mongolian peoples, and it is possible

that decrease in thyroid has affected the people of East Asia

as a whole. So also the Hottentot and the Bushman differ according

to his theory, from the Negro, along lines which might be explained

in part by deficiency in thyroid. The adrenal further controls

sex characters such as hairiness of the face and body. These

are characteristic of European and Australian people, whereas

the Negro and Mongolian are perhaps immature in this respect.

At any rate, such was Keith's thesis.

(53) We may point out what Samuel Brody

observed: (54)

52. Dorsey, George, Why We Behave Like

Human Beings, Blue Ribbon Books, New York, 1925, pp.108,

203.

53. Keith, Sir Arthur, "Evolution of Human Races in the

Light of the Hormone Theory," Johns Hopkins Bulletin,

1922.

54. Brody, Samuel, "Science and Dietary Wisdom," Scientific

Monthly, Sept. 1945, p 216.

pg.21

of 25 pg.21

of 25

Congenital

blindness, missing kidneys, missing limbs (hardly likely to be

inherited), cleft palate, harelip, and other abnormalities were

apparently produced in calves, pigs, and rats by withholding

vitamin A (and also vitamin B2 in rats) from the pregnant mother's

diet. Richardson and Hogan observed about a dozen cases of hydrocephalus

-- characterized by a great skull with little brain -- in newborn

rats from mothers fed a 'synthetic diet' complete in all the

known dietary constituents. Deficiency of some unknown essential

dietary factor may account for this abnormality.

It might be

argued that such observations are not really relevant since it

is in the skull form and in the limb proportions that fossil

man shows the closest resemblance to anthropoid apes, etc. However,

it would not do to overlook the possibility that all these factors

may operate in varying degree, each making its impress upon the

skeletal remains in its own way and to a different extent when

in concert with other influences. Some of the groups of fossils,

particularly Neanderthal specimens, seem so much alike as a whole,

and so uniformly different from modern man, that it has been

customary to assume they represent a true and independent race.

The same was thought of the Anthropus series (Pithecanthropus

and Sinanthropus, which some authorities now classify simply

as Homo sapiens). (55)

But we now have instances in which Neanderthal types are found

intermixed with, and quite clearly contemporaneous with, men

of completely modern type. This is true of the discoveries on

Mount Carmel in Palestine, which revealed a mixed population

that made any clear distinction between the two types impossible

in this instance. (56)

There is a further consideration.

As men multiplied on the earth and began to crowd out the original

settlements, weaker elements in the population would be driven

out. Such people might become waifs and strays, and could well

perish in isolation because of the hardships encountered in a

new and unfamiliar environment. Possibly it is such people whose

remains we find, for as a rule the fossils represent only a very

small group, and often only a single individual. That these remains

should show varying degrees of primitiveness is not surprising.

The extent to which a whole community may suffer in such a manner

was unhappily illustrated some 300 years ago in Ireland. Robert

Chambers has given the story: (57)

The style of living is ascertained

to have a powerful effect in

55. "The Names of Fossil Man," note

in Science, vol.102, July, 1945, p.16.

56. Howells, William, ref.21, p.202. Howells refers to the skull

finds in the following terms: "It is an extraordinary variation.

There seems to have been a single tribe ranging in type from

almost Neanderthal to almost sapiens."

57. Chambers, Robert, Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation,

Churchill, London, 1844.

pg.22

of 25 pg.22

of 25

modifying the human figure in the course

of generations, and this even in its osseous structure. About

200 years ago, a number of people were driven by a barbarous

policy from the counties of Antrim and Down in Ireland, towards

the seacoast: there they have ever since been settled, but in

unusually miserable circumstances.

And the consequence is that they

now exhibit peculiar features of the most repulsive kind, projecting

jaws with large open mouths, depressed noses, high cheek bones,

and bow legs, together with an extremely diminutive stature.

These, with an abnormal slenderness of limbs, are the marks of

a low and barbarous condition all over the world. It is peculiarly

seen in the Australian aborigines.

This is not

an isolated instance. Here is a case in which the "primitive"

appearance of a whole group of people is entirely the result

of historical factors. Undoubtedly these people, given the proper

opportunity, were quite capable of proving themselves in every

sense completely human and probably quite as intelligent as any

so-called "modern" man. Yet if it ever happened that

without any knowledge of the circumstances, their remains were

exhumed by some archaeologist, they might well lead the finder

to suppose he had run across a mass burial of prehistoric men.

Moreover, small isolated populations

whether of animals, insects, or people, tend to vary more widely

than large populations. Viktor Lebzelter formulated the principle

that where the population is large, the culture will be heterogeneous

and the physical type homogeneous, but where the population is

small, the physical types will be heterogeneous but the culture

homogeneous. (58)

The reasons for this are fairly obvious. A small community will

be closely knit in its behaviour patterns and problem solutions

and decorative motifs, etc. But at the same time there will be

a measure of inbreeding that will tend to bring mutant genes

together in a state of homozygosity so they will then manifest

themselves in varieties of new kinds. This is less likely to

happen where the population is large.

But it is also found that when

a single species is introduced into a new environment there is

a tendency for a large number of new varieties to arise almost

immediately. This was first noticed by geologists in studying

the sudden appearance of many new varieties of a species once

they appeared at a certain level in the rocks for the first time.

Sir William Dawson referred to it many years ago. (59) Ralph Linton confirmed

it for man. (60)

Charles Brues illustrated it from entomology. (61) Adolph Schultz, in the Cold Spring Harbor Symposia

58. Lebzelter, Viktor, Rassengeschichte

de Menscheit, Salzburg, 1932, p.27.

59. Dawson, Sir William, The Story of the Earth and Man,

Hodder and Stoughton, London, 1903, p.360.

60. Linton, Ralph, ref.35, pp.26f.

61. Brues, Charles, "Contributions of Entomology to Theoretical

Biology," Scientific Monthly, Feb., 1947, p.130.

pg.23

of 25 pg.23

of 25

for 1950 referred to

it in connection with all primates (68). Colin Selby discussed the mechanism in a paper entitled

"Modern Views of the Origin of Specis". (63) The fact is well known.

Yet, once again, it is not too often that one hears of its relevance

to the present issue. But it is entirely relevant, for one of

the most remarkable aspects of many of the major finds of fossil

man is the variability of types found in a single deposit.

This is true of the fossils from

the Upper Cave at Choukoutien, (64) of the discoveries at Obercassel, (65), and of the group discovered in the Tbun and Skuhl

caves on Mount Carmel in Palestine. (66)

In conclusion we could not do better

than to end with a quotation once more from Wilson Wallis, himself

a veteran anthropologist and one who in spite of his views in

the matter, would still derive man from some lower form of animal

life. His honesty in facing the facts and his courage in stating

his convictions so forthrightly are therefore all the more commendable:

(67)

As regards prehistoric human

remains we cannot conclude that the increasing resemblance to

apes as we go back in time implies simian ancestry, seeing that

these changes may be due to changes in food and posture, representing

the acquisition of form growing out of function or closely correlated

with function. In that case prehistoric man's increasing resemblance

to apes has some other explanation than descent from a common

ancestor, beng, if our interpretation is correct, a case of convergence,

the response of similar form to similar function. . . .

We cannot afford to close our eyes

to facts because we shy away from their implications. A good

case is not strnethened by adducing poor reasons in support of

it, and no fear of giving comfort to the enemy should lead us

to suppose that a partial concelament of truth, which arises

from a concealment of part of the truth, can compensate for the

loss of unprejudiced consideration of the facts of life whether

they seem to fit ino our schemes of evolution or fail to fit.

Since the day of Darwin the evolutionary

idea has largely dominated the ambitions and determined the findings

of physical anthropology, sometimes to the detriment of the truth.

62. Schultz, Adolph, "Man and the Cararrhine

Primates," Cold Spring Harbor Symposia, vol.15, 1950,

p.50.

63. Selby, Colin, "Modern Views of the Origin of Species,"

Christian Graduate, Inter-Varsity Fellowship, London,

June, 1956, p.99.

64. "Homo sapiens at Choukoutien," Antiquity

(England), vol.13, June, 1939, p.243.

65. Weidenreich, Franz, ref.26, p.86.

66. Romer, Alfred, ref.8, p.220.

67. Wallis, Wilson D., ref.17, p.75.

pg.24

of 25 pg.24

of 25

Appendix

Note on S. L. Washburn's Experiment

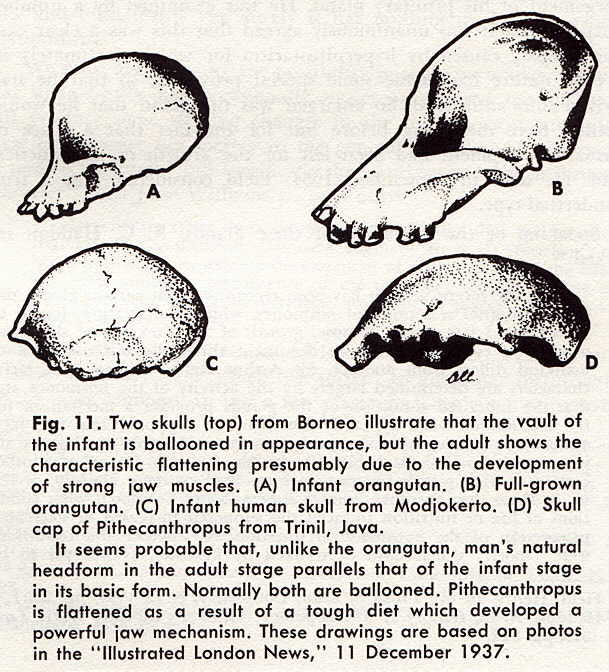

For those who

may happen to be familiar with the experiments carried out by

S. L. Washburn, Department of Anatomy, College of Physicians

and Surgeons, at Columbia University, and reported in the Anatomical

Record (vol.99, 1947, pp.239-248), in which he tried to demonstrate

experimentally the theory of ballooning as propounded by Weidenreich,

the following observations are written.

By severing the chewing muscles

of rats, no alteration was found to occur in the skull form.

It was evidently not possible by such a means to obtain a higher

vault. Washburn's conclusion was therefore that Weidenreich's

theory was without foundation. He went even further when he summed

up his convictions as follows:

Constriction

of the brain case by the temporal muscles could not be demonstrated

in the rat, nor does it seem probable that it occurs in man.

However, this

is going considerably beyond the evidence. There is no reason

to suppose that the rat's gene complement has the capability

of supplying the material necessary to provide a higher vault,

if diet permitted. With man the case is quite otherwise.

Had Washburn added to the

muscular tension instead of reducing it, he might well have obtained

some reduction in what vault there is, and this would

then have supported the thesis we have been proposing in place

of Weidenreich's. (See Fig. 11.)

pg.25

of 25 pg.25

of 25  Copyright © 1988 Evelyn White. All rights

reserved

Previous Chapter *

End of Part IV * Next

Chapter (Part V)

Copyright © 1988 Evelyn White. All rights

reserved

Previous Chapter *

End of Part IV * Next

Chapter (Part V)

|