|

Abstract

Table

of Contents

Introduction

Part I

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Part II

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Part III

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Part IV

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

|

Part I: Technology: the Non-Indo-European

Contribution

Chapter I

The Conquests of Environments

It is

customary to view Western Man as the most inventive creature

who ever lived, and other peoples as unimaginative and backward

by comparison. For this reason it has never surprised those who

write textbooks of History that our own civilization advanced

so far ahead of all that preceded it.

Obviously we are more inventive and so we

have naturally achieved a higher civilization. At one point in time, the

stage was set for the logical development of Science and the proper extension

of a certain innate superiority in controlling the forces of Nature for

our own benefit. Science thus developed automatically. Very few people,

until quite recently, were aware of the achievements of other ancient,

and modern, Cultures which have not shared our tradition. Their arts and

architecture were remarkable enough; but their mechanics and Technology

were of little account except for an occasional odd device like the compass,

etc. And our own uninventiveness as a whole completely escaped notice.

When it was found that Eskimos could be trained to operate and repair

sewing machines and watches as quickly as (if not more quickly than)

we ourselves, some surprise was expressed.

In time the ingenuity of the Eskimo

became increasingly apparent, and writers began to vie with one

another in their search for superlatives to describe these otherwise

'backward' people. But it soon became evident that the Eskimos

were not alone in this. Their conquest of the wilderness of ice

and snow and inhospitable environment is similarly shared by

other primitive people, whom it now turns out have proved themselves

to be quite as ingenious in making the most of the immediately

available resources of their environment. For example, there

are the Indians of the Sonoran Desert in Southern Arizona. Considering

their environment, it is quite amazing to find what they have

succeeded in extracting out of it.

Throughout this discussion of primitive

Culture, and in much of the treatment of more highly complex

civilizations of non-Western tradition, it is necessary to bear

in mind that the greatest displays of ingenuity frequently appear

in the exploitation of the immediate resources of the

environment rather than the secondary or less immediate resources.

This recognition, given somewhat

belatedly, is now being accorded at high levels. Claude Levi-Strauss,

speaking officially for UNESCO, made the following admission

in attempting to establish who has made

pg.1

of 10 pg.1

of 10

the greatest contribution

to the world's wealth:'

If the criterion chosen

had been the degree of ability to overcome even the most inhospitable

geographical

conditions there can be scarcely any doubt that the Eskimo on

the one hand and the Bedouin on the other, would

carry off the palm.

He might equally

well have used the Indians of the Sonoran Desert in place of

the Bedouin. And one could have included another rather rugged

environment, the high altitudes of the Peruvian Andes, where

the Aymara have shown themselves well able to hold their own

with the Eskimo, the Bedouin, and the Indians of Arizona. Let

us examine very briefly some of the achievements of such people.

Ice and snow: the Eskimo

One of the best

modern authorities on this aspect of Eskimo life is Erwin H.

Ackernecht. He writes: 2

The Eskimo

is one of the great triumphs of our species. He has succeeded

in adapting himself

to an environment which offers to man but the poorest chances

of survival. . . .

His technical solution of

problems of the Arctic are so excellent that white settlers would

have

perished had they not adopted many elements of Eskimo technology.

Frederick

R. Wulsin, an authority on clothing problems for cold climates,

says candidly: "There seems to be no doubt that Eskimo clothing

is the most efficient yet devised for extremely cold weather."3 Of this we have had personal

experience, and can affirm its truth without hesitation. Moreover,

to the Eskimo must probably go the credit for developing the

first 'tailored clothing' and, not unnaturally, the first thimbles.4

In addressing

a Scientific Defense Research Symposium in Ottawa, in 1955, Dr.

O. Solandt admitted

1. Levi-Strauss, Claude, "Race and History"

in the series The Race Question in Modern Science, UNESCO,

Paris, 1952, p.27.

2. Ackernecht, Erwin H, "The Eskimo's Fight Against Hunger

and Cold," Ciba Symposia, vol.10, July-Aug., 1948,

p.894.

3. Wulsin, Frederick, R, "Adaptations to Climate Among Non-European

Peoples," in The Physiology of Heat Regulation and

the Science of Clothing, edited by L.H.Newburgh, Saunders,

Philadelphia, PA, 1949, p.26.

4. Jeffreys, Charles, W., A Picture Gallery of Canadian History,

Toronto, ON, Ryerson, 1942, vol.1, p.113.

pg.2

of 10 pg.2

of 10

frankly that

. . . . the White Man has not introduced a single item of

environmental protection in the Arctic which was not already

being used by the natives, and his substitute products are not

yet as effective as the native ones. Only in his means of production

has he the edge.

Ackernecht continues

subsequently:5

A very

short review of the Eskimo's hunting techniques has already revealed

an extraordinary number of well conceived implements. Eskimos

are described as very "gadget minded" and are able

to use and repair machinery such as motors and sewing machines

with almost no instruction. It is impossible to give here a complete

list of aboriginal Eskimo instruments, the number of which and

quality of which have been emphasized by all observers. . . .

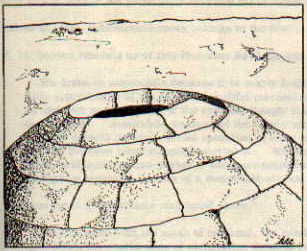

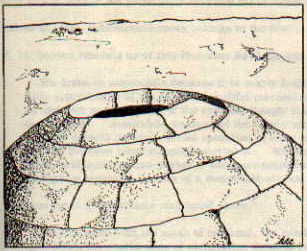

The best known type

of Eskimo house is undoubtedly the dome shaped snow-house with

its ice window. With extraordinary ingenuity, the very products

of the cold are used here as a protection against it.

It might be

thought that once the idea was conceived, the construction of

such a house would be comparatively simple. Actually it is remarkably

difficult to construct a dome without any means of supporting

the arch while in the process of completing it. As the wall rises,

it converges upon itself. Each new block overhangs more and more

until near the top they rest almost in a horizontal plane. The

problem is to hold each block in place until the next one ties

it in, and then to hold that one until it, too, is tied in place.

Given enough hands the problem

is not so difficult, but the Eskimos have overcome the problem

so effectively that a single individual can, if he has to, erect

his own igloo single-handed without too much difficulty.

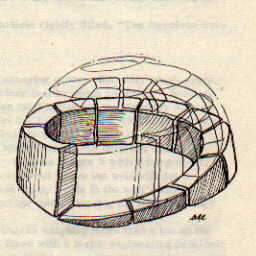

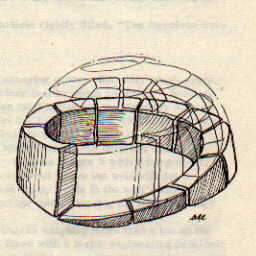

The solution is to carry

the rising layers of blocks in a spiral instead of in a series

of horizontal levels. This is shown in Fig. 1. Thus as each block

is added it not only rests on the lower level, but against the

last block. One block would simply tend to fall in, and, by experience,

so do two or even three, when a new layer is started if the tiers

are horizontally laid. But the Eskimo method overcomes the problem

entirely.

|

|

This is a drawing from a photograph

of an Igloo

at Baker Lake, taken by Mr. Lloyd Wilson of

the Defence Research Board. The original

structure measured 17 feet in diameter. |

A schematic drawing to show how

the spiral construction is initiated. |

Figure 1.

5. Ackemecht, Erwin. H., "The

Eskimo's Fight Against Hunger and Cold", Ciba Symposia,

vol.10, July-Aug., 1948, p. 897.

pg.3

of 10 pg.3

of 10

The

solution is, of course, amazingly simple -- once it is known.

. . . Most solutions are, when someone has discovered them

for us! The problem is to visualize the solution before it exists.

We tend to assume we would discover the way quite quickly but

experience shows that this is not true. As A. H. Sayce has put

it so well, "one of the most significant lessons of Archaeology

is that man is not essentially creative but destructive"

and among ourselves at least, "constructiveness belongs

to the few." 6

H. M. Davies

reminds us of this fact when he eloquently pointed out:7

We

drive an automobile because it is nearly foolproof, with little

appreciation of the hidden, beautiful mechanism that powers it,

and with no conception of the creative thought that went into

its development: meanwhile we demand the family airplane. We

listen to a radio receiver whose operation is utter magic to

us and demand the even more complex television. We are a race

of lever-twiddlers, button-pushers, and knob-twisters, enjoying

the prodigious technical labours of a comparatively few men.

As Sayce

put it in the article mentioned above,8

As compared with the mass

of mankind, the number of those upon whom the continuance of

civilization depends is but small; let them be destroyed or rendered

powerless, and the culture they represent will disappear.

But to

return for a moment to the Eskimo again: because his environment

offers him little in the way of raw materials, his solutions

must always seem simple in nature. It is all the more to his

credit that he has achieved so much. Dr. Edward Weyer in an article

rightly titled, "The Ingenious Eskimo," puts the matter

this way;9

Take the Eskimo's

most annoying enemy, the wolf, which preys on the caribou and

wild reindeer that he needs for food. Because of its sharp eyesight

and keen intelligence, it is extremely difficult to approach

in hunting. Yet the Eskimo kills it with nothing more formidable

than a piece of flexible whalebone.

He sharpens the strip of

whalebone at both ends and doubles it back, tieing it with sinew.

Then he covers it with a lump of fat, allows it to freeze, and

throws it out where the wolf will get it. Swallowed at a gulp

the frozen dainty melts in the wolf's stomach and the sharp whale

bone springs open, piercing the wolf internally and killing it.

. . .

When the Eskimo gets a walrus

weighing more than a ton on the end of a harpoon line, he is

faced with a major engineering problem: how to get it from the

water on to the ice. Mechanical contrivances belong to a world

in whose development the Eskimo has had no part. No implement

ever devised by him had a wheel in it. Yet this does not prevent

him from improvising a block and tackle that works without a

pulley. He cuts slits in the hide of the walrus,

6. Sayce Archibald, H., "Archaeology

and Its Lessons," in Wonders of the Past, edited

by Sir John Hammerton, Putnam's, London, 1924, vol.1, p.10.

7. Davies, H.M., "Liberal Education and the Physical Sciences,'

Scientific Monthly, vol.66, no.5, May, 1948, p.422.

8. Sayce, A.H., "Archaeology and Its Lessons"

in Wonders of the Past, edited by Sir John Hammerton,

Putnam's, London, 1924, vol.1, p.11.

9. Weyer, Edward, "The Ingenious Eskimo," in Natural

History, published by Natural History Museum, New York, May

1939, p.278, 279.

pg.4

of 10 pg.4

of 10

and a U-shaped hole in the ice some distance

away. Through these he threads a slippery rawhide line, once

over and once again. He does not know the mechanical theory of

the double pulley, but he does know that if he hauls at one end

of the line, he will drag the walrus out of the water onto the

ice. [For illustration see Fig. 2]

Figure 2.

The deceiving

thing about his ingenuity is in its very simplicity! He makes

hunting devices of all kinds, that are effective, inexpensive

in time, easily repaired, and uses only raw materials immediately

available. His harpoon lines have floats of blown-up skins attached,

so that the speared animal is forced to come to the surface if

he dives. To prevent such aquatic animals from tearing off at

high speed dragging the hunter and his kayak, he attaches baffles

to the line which are like small parachutes that drag in the

water. A bone hoop and a skin diaphragm stretched over it, and

some thongs, are all that he needs.

To locate the seal's movements

under the ice he has devised a stethoscope which owes nothing

to its modern Western counterpart working on the same principle.10 And recently a native 'telephone'

was discovered in use, made entirely from locally available materials,

linking two igloos with a system of intercommunication the effectiveness

of which was demonstrated on the spot to the Hudson's Bay Agent,

a Mr. D. B. Marsh who discovered it. Marsh adds at the end of

his report, this statement:11

The most amazing thing

of all was that no one in that camp had ever seen a telephone,

though doubtless they had heard of them from their friends who

from time to time visit Churchill.

Nevertheless,

it is exceedingly unlikely that any such friends who had seen

a telephone, would have seen the kind of arrangement this Eskimo

had developed which of course used no batteries. We used to make

a similar kind of thing as children with string and ordinary

cans, but they were never very much use, and in any case we got

the idea from someone else. In this case the Eskimo had used

fur around the diaphragm to cushion it, and the sound came through

remarkably well.

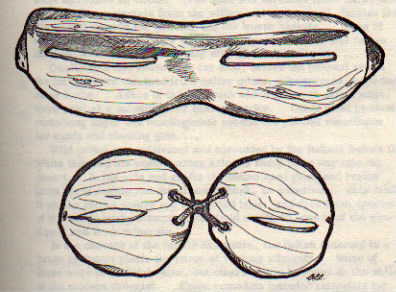

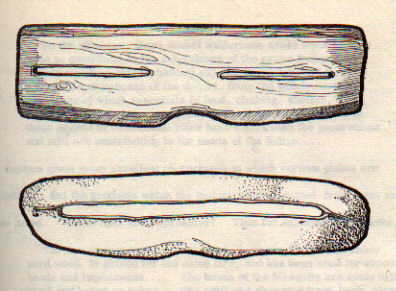

Figure 3.

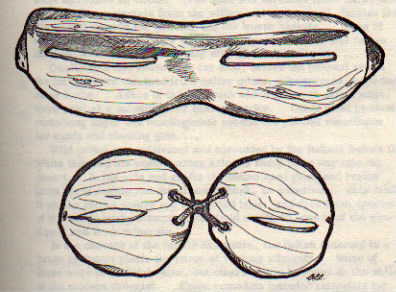

And finally, a word about Eskimo

snow goggles. A plate of illustrations of these protective devices

is given in Fig.3. These are well known to Arctic explorers,

and no one will travel in the Arctic without them -- or something

to replace them -- if he wishes to escape the very unpleasant

ailment of snow blindness.

10. An illustration of such an instrument

is given by Alexander Goldenweiser, Anthropology, Crofts,

New York, 1937, p.85, fig.23.

11. Marsh, D. B., "Inventions Unlimited", The Beaver,

published by The Hudson's Bay Co., Dec., 1943, p.40

pg.5

of 10 pg.5

of 10

Like everything else the Eskimo

makes, they are very effective, and often so designed that he does not

need to turn his head to see to either side of him. This is important,

since the game he usually hunts would catch the movement.

Deserts: Indians of the Sonoran

Turning now

to the Indians of the Sonoran Desert, Macy H. Lapham has written

illuminatingly of their genius for making much of little. He

writes:12

To the

stranger, these desert wilderness areas seem to have little to

contribute to the subsistence of the native Indian . . . . Notwithstanding

this forbidding aspect, to the initiated there is a veritable

storehouse of the desert, from the widely scattered resources

of which essentials in food, clothing, shelter, tools, cooking

utensils, fuel, medicine, and articles of adornment or those

sacred in ceremonial rites have contributed for generations and

still are contributing to the needs of the Indian. . . .

Lapham gives

many excellent photographs in which various plants are identified

-- and the products which the Indians have extracted from them

are also listed. These lists are impressive! Thus for example

he remarks:

The

desert ironwood, a small tree, is known for its extremely hard

wood, is prized for the camp fire, and has been used for arrow

heads and implements. . . . The beans of the Mesquite are made

into meal and baked as cakes. The split and shredded inner bark,

along with similar materials from the willow and cotton wood,

furnish the fibres and strands for building and for woven baskets.

Some of these baskets are so finely woven that coated with gum

and resins obtained from the desert plants they may be used for

liquids. . . .

Condiments and seasonings

for food, before the present era of the tin can were obtained

from native mints, pepper grass, sage and other herbs. Ashes

of the salt bush which grows in saline soils, were used as a

substitute for baking powder. Other plant products containing

sugar and mucilaginous substances yielded substitutes for candy

and chewing gum. . . .

Wild cotton was cultivated and

harvested by the Indians before the White Man and his wool-bearing

animals found their way into the desert. In his arts and crafts

the Indian used gums and resins from the Mesquite and the creosote

bush, as adhesives; awls made from the cactus spines and sharpened

bone; and dyes from species of the indigo bush, mesquite, the

fetid marigold, seeds of the sunflower, and from minerals.

In the absence of the family drugstore,

the Indian resorted to a range of desert plants for cures of

various ailments. Some of these were of doubtful value, but others

are to be found on the shelf of the modern druggist. These remedies

included materials for poultices and infusions, and decoctions

of the manzanita, creosote bush catnip, canaigre or wild rhubarb,

verba santa or mountain balm, verba mansa, the inner bark of

the cotton wood, winter fat,

12. Lapham, Macy H., "The Desert

Storehouse," Scientific Monthly, vol.66, no.6, June,

1948, p.451ff.

pg.6

of 10 pg.6

of 10

golden aster, goldenrod, yarrow, horsebrush, and

species of the sunflower. They were used for sore throats, coughs, respiratory

diseases, boils, toothaches, fevers, sore eyes, headaches, and as tonics

and emetics. Mullein leaves were smoked and used for medicinal purposes,

while roots of the yucca, winter fat, and four o'clock, and leaves of

the seepweed, were used as laxatives and for burns and stomach ache.

There was even an insecticide -- a sweetened infusion of the leaves

of the Haplophyton or cockroach plant which was used as a poison

for mosquitoes, cockroaches, flies and other pests.

Even such random

excerpts from Lapham's article might be sufficient indication

of the 'inventiveness' of these so-called primitive people. But

there is much more to wonder at.

A photograph of a Mesquite thicket in

a river bed is accompanied by this observation:

Mesquite thickets supply fuel,

poles, timbers for buildings and fences, and fibres and strands

for baskets and binding materials. From the mesquite's bark,

seed pods, and bean-like seeds come food, browse for livestock,

medicine, gums, dyes, and an alcoholic beverage.

The roots of

the Yucca trees supply drugs and a 'soap substitute.' Like the

pioneer farmers, it seems that they use everything but the noise!

Lapham concludes:

Thus, as the Indian made his

rounds of this self-help commissary in an apparently empty wasteland,

be found an impressive stock to be harvested and added to his

market basket. We can only marvel at the wisdom and vast store

of knowledge accumulated by these primitive people as they made

the desert feed, clothe and shelter them.

This is a long

quotation. But it serves to indicate what ingenuity can do with

an otherwise unpromising environment. It is difficult indeed

to conceive of a more complete exploitation of the primary resources

of the desert in which they have been content to live.

Ingenuity

One wonders if Lapham's use of

the word 'found' is really just. They seem virtually to have

exhausted their environment, extracting from it wisely, ingeniously,

and effectively all it could possibly afford. Would we have 'found'

much of this I wonder. . . .

The

point I should like to emphasize particularly here is that such

people, for so long supposedly unimaginative and dull, have demonstrated

a remarkable genius for this kind of thing. Their ingenuity has

been

pg.7

of 10 pg.7

of 10

overlooked so often because those

who surveyed their work were themselves unaware of the effort required

to invent anything. It all seems so obvious. Their solutions to

mechanical problems in particular are always characterized by a peculiar

simplicity that is completely deceiving.

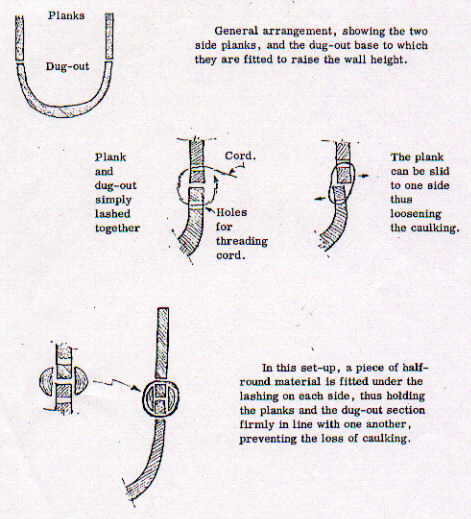

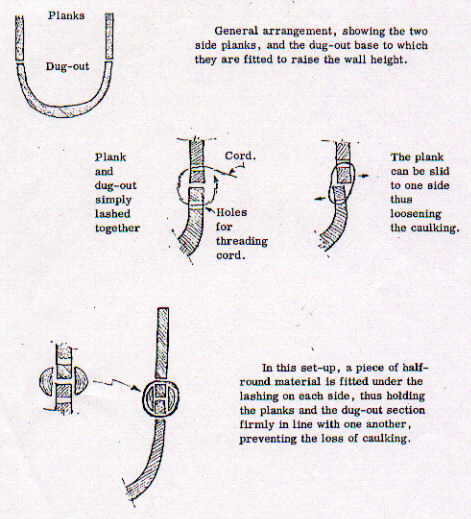

To digress for a moment,

we may use as an illustration of this aspect of primitive technology,

a method used by Polynesians to build the plank walls of their

canoes. Anyone who has ever tried to bind two planks together

edgewise, so that they will be tight and rigid -- and will remain

so -- will have quickly discovered how difficult it is. It is,

in fact, almost impossible. Yet the Polynesian canoe builders

do it easily. Figure 4 shows how it was done. In a sense,

it really takes an engineer to see the genius of this. By using

gums and resins in the joint, a perfectly rigid, strong, and

watertight union is effected. The solution seems obvious enough.

Such ingenuity was exercised wherever their comparatively simple

needs were not completely satisfied because of some mechanical

obstacle.

Perhaps one more such 'simple'

solution may be in order here. The Indians of North America used

leather for clothing -- the familiar buckskin. However, one problem

of all such materials is that after a while the edge begins to

curl up or to roll in such a way as to be both unsightly and

ill-fitting, and of course colder in winter. This was overcome

by making a series of cuts into the edge and at right angles

to it, each cut being about two inches long, and spaced about

one-sixteenth of an inch to one-eight of an inch apart. This

imparted to the edges the familiar 'frill' effect, which is both

decorative and fundamentally useful. It required virtually nothing

to do it -- except ingenuity in the first place. It prevents

edge-curling entirely.

Deserts: ancient Nabateaens of the Transjordan

Desert areas always seem to hold

so little promise of survival to the sophisticated European.

The very appearance of barrenness seems to hinder the processes

of thought which would otherwise find how to render it more habitable.

But it seems to have been no great problem to non-Indo-European

people, whether ancient or modem.

Recent archaeological exploration

in the desert area of Transjordan has revealed a remarkable triumph

of early irrigation engineering. Michael Evenari and Dov Koller

reported recently on the results of their work in the Negev.13

13. Evenari, Michael, and Dov Koller, "Ancient

Masters of the Desert," Scientific American, April,

1956, p.36ff.

pg.8

of 10 pg.8

of 10

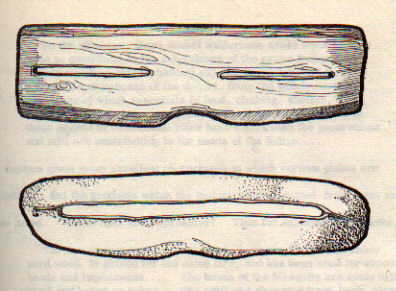

|

Anyone who will try this experiment for themselves

will find that it is impossible to secure two pieces of planking

together securely so that they will not move out of line. This

method is completely effective.

|

Figure 4.

pg.

9 of 10 pg.

9 of 10

The idea

that anyone could have farmed a desert as arid as this is today,

seemed so incredible that many authorities concluded the climate

of the region must have been more lush in the time of the Nabataeans.

Nelson Glueck went to Palestine in the 1930's and to Transjordan,

to re-explore the Nabataean Culture, and what he found led him

to acclaim the Nabataeans as "one of the most remarkable

people that ever crossed the stage of history." Their cities

did indeed bloom in the midst of a seemingly hopeless desert.

Nowhere in all their houses was there a stick of wood to show

that any trees had ever grown in the region.

The authors

then explain how these ancient people achieved a greater mastery

of the desert than any other people since, and they underline

the fact that the Nabataeans "avoided the mistake"

of trying methods which are the universally accepted Indo-European

ones, namely the use of dams. Their method was cheaper, more

effective, more readily controlled, and brought a greater area

of desert land under successful cultivation. They so prospered

in fact, as to be able to build and support the very famous city

of Petra. The authors then describe the method of irrigation

these people employed. And in summing up, they remark -- to quote

their own words:

The more one examines the Nabataeans'

elaborate system, the more impressed one must be with the precision

and scope of their work. Engineers today find it difficult enough

to measure and control the flow of water in a constantly flowing

river, but the Nabataean engineers had to make accurate flow

estimates and devise control measures for torrents which rushed

over the land only briefly for a few hours each year. They anticipated

and solved every problem in a manner which we can hardly improve

upon today. Some of their structures still baffle investigators.

Records

tell that the yield was often seven or eight times the sowing.

As the authors conclude:

The Nabataeans' conquest

of the desert remains a major challenge to our civilization.

With all the technological and scientific advances at our disposal

we must still turn to them for some lessons . . . the best we

can do today is no more than a modification of the astute and

truly scientific methods worked out more than 2000 years ago

by the Nabataean masters of the desert.

Snowy waste, or sandy

desert, bitter cold or stifling heat -- we have little to contribute

in the conquest of such environments.

pg.

10 of 10 pg.

10 of 10  Copyright © 1988 Evelyn White. All rights

reserved

Introduction Next

Chapter

Copyright © 1988 Evelyn White. All rights

reserved

Introduction Next

Chapter

|