|

Abstract

Table

of Contents

Introduction

Part I

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Part II

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Part III

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Part IV

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

|

Part I: Technology: the Contribution of Non-Indo-Europeans

Chapter II

The Achievements of Primitive Cultures

To return to

the New World again, J. Grahame Clark, speaking of the contributions

made by the Indians of North and South America to the Old World,

has this to say:14

Baron Nordenskiold, unlike

some European theorizers, who found it difficult to credit the

aborigines with the ability to raise their own civilization independently

of the Old World inspiration, had spent many long and arduous

years in the field of South American archaeology, and his conclusions

carried with them outstanding authority. In addition to many

technical inventions he attributed to the American Indian the

achievement of domesticating the animal and plant life of his

habitat so effectively that during the four centuries since the

Discovery the White Man had failed to make a single contribution

of importance. The native fauna gave poor scope, but from it

he domesticated the llama, alpaca, guinea-pig, and turkey. Of

plants he domesticated hundreds. . . .

Matthew Stirling,

Chief of the American Bureau of Ethnology at the time of this

writing, speaks of this contribution thus:15

Among the plants developed

by these ancient botanists are maize, beans (kidney and lima),

potatoes, and sweet potatoes, now four of the leading foods of

the world. Manioc, extensively cultivated by the natives of tropical

America is now the staff of life for millions of people living

in the equatorial belt. Other important items, such as peanuts,

squash, chocolate, peppers, tomatoes, pineapples and avocados

might be added.

In addition the Indian was the

discoverer of quinine, cocaine, tobacco, and rubber, useful commodities

of modern times. Maize or Indian corn was one of the most important

contributions of the American Indian to mankind. Over a considerable

portion of the Americas, it was the staff of life.

Kenneth Macgowan

adds to this list, the custard apple, strawberry, vanilla bean,

chickle, and cascara, besides a number of others less familiar.

His whole list of important plants made up by the Indian's agriculture

is impressive, as he says, for it contains 50 items, not

one of which is an Old World species! 16

Every one of them can be cultivated

with a hoe, requiring no draft animals whatever. He also mentions

one other accomplishment which is very difficult to account for.

The Indian devised a method of extracting a deadly poison (cyanide)

from

14. Clark, J. Grahame, "New World Origins,"

Antiquity, vol.14, no.54, June, 1940, p.118.

15. Stirling, Matthew, "Americas First Settlers, the Indians,"

National Geographic Magazine, Nov., 1937, p.592.

16. Macgowan, Kenneth, Early Man in the New World, Macmillan,

New York, 1950, p.199 and 202 (cyanide)

pg.1

of 20 pg.1

of 20

an otherwise useless

plant, manioc, without losing the valuable starch it contained.

Macgowan says that Henry J. Bruman called this "one of the

outstanding accomplishments of the American Indian." The

remarkable thing about it is that they should ever have thought

of making use of a plant which, as they found it, contained a

deadly poison.

M.D.C. Crawford gives a list of

vegetables which were cultivated by the American Indians prior

to 1492, which in addition to the above are the following:17

aloe Jerusalem

artichoke

alligator Pear

pineapple

arrowroot Indian

fig (Prickly pear)

cacao pumpkin

chili pepper star

apple

cotton (gossypium barbadense Linn.)

J. L. Collins

wrote more recently:18

The pineapple shares the

distinction accorded to all major food plants of the civilized

world, of having been selected, developed, and domesticated by

people of prehistoric times, and passed on to us through one

or more earlier civilizations. The pineapple, like a number of

other contemporary agricultural crops . . . originated

in America and was unknown to the people of the Old World before

its discovery.

Just where

the Indians found the original plants which they improved upon

to produce modern pineapples, we do not now know. None of the

existing varieties compares with the domesticated product, and

as Collins observes, "none of these can be singled out now

as the form or forms which gave rise to the domesticated pineapples

of today, or even of those varieties in the possession of the

Indians at the time of the Discovery of America." This was

no accidental by-product then, but a deliberate and intelligent

breeding process which progressed so far before we knew anything

about it, that we cannot now retrace the steps by which it was

first accomplished.

Melville Herskovits19 points out that the North

American Indians increased the fertility of their land artificially,

by putting a fish in each Maize hill, and practiced multi-planting

highly successfully. In each hill

17. Crawford, M.D.C., The Conquest of Culture,

Fairchild, New York, 1948, p.145, 146.

18. Collins, J.L., "Pineapples in Ancient America,"

Scientific Monthly, vol.66, no.11, Nov., 1948, p.372.

pg.2

of 20 pg.2

of 20

planted with Maize they

placed squash and bean seeds together, so that the bean plants

could climb the corn stalks and the squash vines run along the

ground. The same practice is apparently found in West Africa,

where gourds take the place of squashes. Their reasoning here,

as Herskovits points out, is different from ours: they hold that

a plant which grows erect, one that climbs, and one that hugs

the earth must each have a different nature and therefore extract

a different food from the earth.19 Thus they will not compete with each other.

Speaking of the Orient, Dr. F.

H. King who has made a most careful examination of the farming

methods practiced by the Chinese, the Koreans, and the Japanese,

drew special attention to their painstaking care in maintaining

or enhancing the fertility of their soils using all kinds of

fertilizers and other special means. 20

Ingenuity: in food gathering

Necessity is the Mother of invention

(although laziness helps!) and food is a necessity. Primitive

people have shown extraordinary ingenuity in obtaining food.

We have already mentioned one or two devices used by the Eskimo

. . . the spring bone for killing wolves, for example. In other

parts of the world there is the same remarkable ingenuity --

and not the least remarkable element is the variety.

For example, according to George

P. Murdock, the Ainu of Northern Japan use dogs to do their fishing

for them. There are shoals of fish in the shallow water along

some of their coasts, and to catch these they have trained their

dogs to swim straight out to sea in a line until a given signal.

The dogs then wheel around and come back in an arc towards the

shore, barking and making a big splash thus driving the fish

into even shallower water where each dog seizes one in his mouth,

runs ashore, and drops it at his master's feet receiving the

fishes' heads as a reward! 21

Ralph Linton speaks of one

device for catching wild fowl, which he feels should certainly

be awarded top prize for simple ingenuity.22 A flat stone of about 18 inches diameter is given

a small raised rim of mud or clay, and certain nuts are placed

in the enclosure. These nuts are a particular delight of the

local guinea fowl. But the natives of several parts of Africa

where these birds are found, take care to ensure that the nuts

are just too large for the fowl to pick up in their beaks.

Attracted to the food, the birds

try again and again to get a nut in their mouth, each time striking

the flat rock with their beak instead. They are persistent creatures

apparently, and so they keep it up until their beaks

19. Herskovits, Melville, Man and His Works,

Knopf, New York, 1950, p.250.

20. King, F.H., Farmers for 40 Centuries, Emmaus, PA,

Rodale Press, reviewed in Scientific Monthly, vol.66,

Dec., 1948, p.448, by W.M. Myers, under the title, "Those

Clever People."

21. Murdock, George P., Our Primitive Contemporaries, New

York, Macmillan, 1934. p.167.

22. Linton, Ralph, The Tree of Culture, New York, Knopf,

1956, p.83.

pg.3

of 20 pg.3

of 20

are quite swollen and

they have literally knocked themselves silly. Each day the owner

of the stone calls by and picks up the stupefied birds from the

immediate neighbourhood.

Poultry farmers have found that

the same thing can happen to chickens fed on a concrete floor.

But there is no evidence that Indo-Europeans ever put this observation

to any practical use.

We may mention a further example

of native ingenuity in this connection which is found in certain

parts of Oceania, where there are cuttlefish which have long

sucker-tipped arms that are stretched out to catch fish. The

natives attach these cuttlefish to lines and use them to catch

food for themselves instead. 23

Lord Raglan tells how in some areas

of Oceania, the natives of Java, of the Banda Islands, and the

Dobuans, catch a particular species of fish that is difficult

to approach, by using fishing-kites.24 The kite is flown on a line of some length, and the

fish hook dangles from the tail of the kite, thus allowing the

fisherman to keep a considerable distance from the fish which

would otherwise evade him.

It is well known that the Japanese

have for years used Cormorants to do their fishing for them.25 The birds seem to be well

trained and to enjoy themselves immensely! The Samoans use a

native plant drug which, when poured on the water, makes the

fish dopey and easy to catch. 26 According to Carleton Coon, the Australian aborigines

poison the water holes with a mild drug that similarly makes

the animals who drink from them stupefied. By such means, for

example, they easily catch the swift-footed emu. 27 A paper published by the

Smithsonian Institution lists hundreds of such poisons used by

primitive people in all parts of the world to catch game. 28

The Terra del Fuegians have so

many different traps and other devices for catching ducks and

geese, etc., that it would be wearying to detail them. Coon refers

to them as being many, and ingenious, and varying according to

the nature of the locality. 29 They are moreover characterized by a remarkable degree

of

23. Cotton, Clare M., "Animals: Old Hands

at Angling," Science News Letter, Mar. 6, 1954, p.155

24. Raglan, Lord, How Came Civilization? London, Methuen,

1939, p.130.

25. Gudger, E.W. "Fishing with the Cormorant in Japan,"

Scientific Monthly, vol.29, July, 1929, p.5ff.

26. Murdock, George P., Our Primitive Contemporaries, New

York, Macmillan, 1934, p.51.

27. Coon, Carleton S., A Reader in General Anthropology,

New York, Henry Holt, 1948, p.220.

28. Heizer, Robert F., "Aboriginal Fish Poisons," Paper

No. 38, in Anthropological Papers, Bulletin 151, Smithsonian

Institution, Washington, 1953, p.225, 283. Several hundred

poisons are listed.

29. Coon, C.S., A Reader in General Anthropology, New

York, Henry Holt, 1948, p. 220.

pg.4

of 20 pg.4

of 20

originality, so that

it becomes difficult to imagine any further alternatives. Yet

these same Terra del Fuegians were considered by Darwin, when

he visited them during his voyage with the Beagle, to

be the very lowest of all humans

-- hardly people at all.30 Sir John Lubbock shared this opinion.31 Yet their inventiveness

where it had to be exercised knew almost no limitations.

Inventions: simplicity the hallmark of

genius

I should like to draw attention

to this point, here. Inventiveness was exercised where needs

arose, seldom otherwise. And this inventiveness did not (as ours

so often does) display itself by merely modifying the products

of others. The results were as diverse as they were original,

and they are almost always characterized by a grand simplicity

that is completely misleading to the Westerner whose products

are so terribly complicated. Yet simplicity is the essence of

genius.

Take as an illustration of this,

the bola. Here is a weapon that is effectiveness itself in bringing

down small rapidly moving game. The device is composed of a number

of stones (usually about 2 to 3 inches in diameter), around each

of which a cord is fastened in a groove with a free end about

12 to 18 inches long. From four to eight such stones form the

weapon, which is made by tying together the free ends of the

long cords. Holding these cords at their junction, the native

swings the stones around like a windmill and lets the whole affair

fly at a flock of birds, or rabbits, or other such small game.

The stones tend to part company in flight, but only of course

to the extent of the cords which tie them to one another. The

weapon is thus widely spread by the time it reaches the game,

and the chance of a hit is greatly increased. The same effect

is of course obtained with 'shot.' However, if any one of the

stones makes contact or if any of the cords do, the whole weapon

at once wraps itself around the victim and down it comes! What

could be simpler?

These bolas are found in many parts

of the world, and even in prehistoric sites -- a mute testimony

to the inventiveness even of prehistoric man,32 for it seems hard to believe that they were invented

only once and that all modern instances are derivatives.

Of all primitive

people, perhaps the Australian aborigines have aroused the most

interest, not merely because they are so well known and among

the last to retain to a large extent the greater part of their

ancient skills and traditions, but also because of the extraordinary

simplicity of their material culture. Virtually the whole of

a man's worldly wealth can normally be carried with him, often

in one hand! Of added interest, of course, is the fact they seem

to be negroid (because so very black) and yet have much body

hair and bushy beards -- which negroes never have: thus their

origin is somewhat of an intriguing mystery still.

30. Darwm, Charles, Journal of Researches,

New York, Ward, Lock and Co., preface dated 1845, p.206ff.

31. Lubbock, Sir John, Prehistoric Times, New York, New

Science Library, J.A. Hill, 6th edition, revised 1904, p.201.

32. Bolas: see Robert Braidwood, Prehistoric Man, Chicago,

Field Museum of Natural History, in Popular Series: Anthropology,

No.7, 1948, p.56.

pg.5

of 20 pg.5

of 20

But

their ingenuity is also undoubted in so far as they have cared to exercise

it. Probably the supreme example of this is the boomerang. These weapons

are also found in other parts of the world, and even in prehistoric sites.

33 As a weapon, it is remarkable: and it has quite justly been

called the first 'guided missile.' Of course, all thrown objects are 'guided'

in a sense; but the boomerang can be so controlled in the hands of an

expert that it will do extraordinary things in the air, and return to

the sender if it misses the target -- a great saving of effort, and a

real advantage in war!

George Farwell recently authored

an official Australian Government paper on this device, in which

the design of the weapon is carefully considered. It is a much more complex

affair than would appear to the casual observer. Its response

to controlled flight is outlined by the author who then explains

how this is possible. It is a technical achievement of no mean

order, and one wonders what was going on inside the native's

mind who perfected it. Even if its special construction features

were purely accidentally discovered at first, it is still true

that the inventor discovered his discovery. This is not merely

a play upon words. As we shall see subsequently, Indo-Europeans

are still making notable discoveries and not recognizing them

for what they are. Of the boomerang, Farwell writes:34

There are sound reasons

for its design features. The undersides of the arms are flat,

the upper have a slight camber, a factor which provides lift.

There is also a twist from the horizontal at the outer end of

each arm, one upward, the other down, perhaps not more than two

degrees in all. It may seem unreal to discuss a prehistoric weapon

in terms of aerodynamics, but therein lies the remarkable achievement

of the aborigine. His practical mind and acute observation anticipated

certain ideas of the 20th century aircraft designers.

Sir Thomas Mitchell, the

explorer, made the characteristic twist of the boomerang the

basis for a new type of ship's propeller, which he patented 100

years ago. Early in this century G. T. Walker of Cambridge University,

spent no less than ten years of research into the boomerang's

properties, evolving certain theories on gyroscopic flight.

33. Boomerangs: these have also been reported

from Egypt at Badari by Vere Gordon Childe, (New Light on

the Most Ancient East, London, Kegan Paul, 1935, p.65),

and in Europe by Herbert Wendt, (I Looked for Adam, London,

Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1955, p.356).

34. Farwell, George, "The First Known Guided Missile,"

reprinted in the Globe and Mail, (Toronto, ON, Saturday,

Aug., 29, 1953, p.17), as a feature article, from the Australian

Government publication, South West Pacific.

pg.6

of 20 pg.6

of 20

Farwell then elaborates somewhat on the dynamics of its flight

and gives some examples of feats which the natives can achieve with very

little effort. He presumes that it was perhaps by observing the flight

of falling leaves with their curled up edges that the natives came to

the idea. This sounds rather weak to me. At any rate, they created a very

ingenious weapon, and we have found no way to improve it yet.

George Sarton uses this weapon

as an illustration of "the uncanny ingenuity of 'primitive'

people." To this he adds the elastic plaited cylinder of

jacitara palm bark, called a tipiti, which is used to extract

the poison cyanide from the Manioc to which reference has already

been made. As a third illustration he refers to the prehistoric

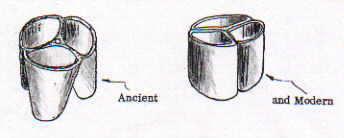

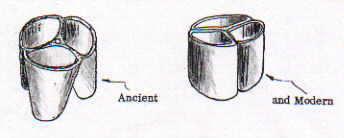

Chinese pottery vessels which took the form of a tripod, the

legs of which were hollow and formed the containers.35 It thus anticipated by thousands

of years the modern trisection aluminium wares! It is illustrated

roughly in Fig. 5. The legs straddled the fire. The shape, of

course, permitted cooking three separate dishes at one time

Figure 5.

Ingenuity: in medical skills

In the Peruvian Andes, living at

an elevation of 14,000 feet approximately, are the Aymara --

believed to be the remnants of the creators of the Inca Empire.

They are a rather impatient and ill-tempered people according

to some observers, possibly by reason of the rarefied atmosphere

in which they live, and possibly on the same account they do

not care to exert themselves much to improve their condition

-- although obviously this was not true in the past. But they

have developed their medical skill quite extensively, and so

organized the Profession that there are specialists in the various

fields who refer patients to one another as seems necessary.36 Like most primitive people,

they mix magic with their medicine: but they evidently realize

that the magic has a psychological value as much as anything.

This is true of other such native people. A. P. Elkin has written

on this point at some length and is convinced that the Witch

Doctor is often a man, as he put it, of "High Degree"

by which he means relatively a Ph.D. in the context of his own

culture. 37 The

relationship between magic and medicine, and indeed Science in

general, is considered later. In the meantime it is becoming

increasingly apparent that the non-Indo-European far anticipated

us in their medical practice, as well as in the field of Psychology.

I think this is particularly true in certain areas, such as in

the problem of dealing with fear. Speaking of African medical

skill, Grantly Dick Read points out: 38

35. Sarton, George, A History of Science,

Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press, 1952, p.5.

36. Tschopik, H., Jr., "The Aymara," in Handbook

of South American Indians, published by the Bureau of American

Ethnology, 1946, vol. 2, Bulletin 143, p.501-573.

37. Elkin Adolphus P., Aboriginal Men of High Degree, being

the 1944 Queensland University John Murtagh Macrossan Memorial

Lectures, published by Australasian Publications, 1946.

38. Read, Grantly Dick, "No Time for Fear," as

reviewed by W.A.Deacon in the Saturday Review of Books, Globe

and Mail, Toronto, ON, Aug., 11, 1956.

pg.7

of 20 pg.7

of 20

They had cures for

diseases which modern science still finds difficult to heal -- and sometimes

the knowledge of a good witch doctor could be of very good use to modern

psychology.

Frequently,

of course, they did not reflect much upon the psychology they

used -- but it was always very practical in its application,

and it represented a kind of deep wisdom which modern physicians

sometimes lack.

There are often amusing and revealing illustrations of this.

In two areas in particular they explored widely -- in person-to-person

relationships, especially with near relatives, and in dealing

with the supernatural. For example, they insist as a rule that

a man go to live with his wife's people. There are a number of

very good reasons for this, not the least of which is the fact

that they recognized that most emotional tensions revolve around

the lady of the house. When a man goes to his wife's home, the

lady of the house 'gains' a son. If, however, the wife goes to

the husband's house to live, the lady of the house 'loses' a

son! This is a serious thing -- the root of much jealousy and

causes emotional tensions which they sought to avoid.

As an illustration of the

second area in which Psychology is applied, one can cite a case

that occurred in a Pueblo village after the last war. Many young

Hopi volunteered for service overseas. This often badly confused

their traditional cultural behaviour patterns. One anthropologist

noting this, suggested to a young Hopi veteran that he'd still

be afraid to sleep in one of their ancient cemeteries. He laughingly

denied this. So he, and an old villager, agreed to the test.

The old man selected a spot to sleep, performed several little

rites, sprinkling seed around his bed and urinating on the seed.

With a brief prayer, he then lay down and slept like a child.

The young man no longer believed in such things -- neither the

spirits (so he said) nor the 'magic.' He tossed and turned, quite

unable to sleep -- pretending to be unafraid and having no longer

any accepted means to offset the fears he denied. He finally

got up and returned to the village! A. P. Elkin gives many instances

of this kind of thing in Australia, and says that he often spoke

to the old men about their faith in the magic they used and was

surprised to find how clearly they understood its psychological

value. Some of the witch doctors were Ph.D.'s in Psychology,

rather than doctors with an M.D., according to Elkin.

But even in the use of drugs that

do actually work chemically the non-Indo-European has been far

ahead of us. Aldous Huxley speaks of the use of such drugs and

tranquilizers and other remedies for anxiety: 39

Certain chemical compounds produce certain changes of consciousness

and so permit a measure of self-transcendence and a temporary

relief of tension. Thus, the so-called "tranquilizing drugs"

are merely the latest addition to a long list

39. Huxley, Aldous, "History of Tension,"

Scientific Monthly, vol.87, July, 1957, p.4, 5.

pg.8

of 20 pg.8

of 20

of chemicals which have been used from time immemorial

for changing the quality of consciousness and so making possible some

degree of transcendence. Let us always remember that, while modern pharmacology

has given us a host of new synthetics, it has made no basic discoveries

in the field of the natural drugs; it has merely improved the methods

of extraction, purification, and combination. All the naturally occurring

sedatives, narcotics, euphorics, hallucinogens, and excitants were discovered

thousands of years ago before the dawn of civilization. This surely

is one of the strangest facts in that long catalogue of improbabilities

known as human history. Primitive man, it is evident, experimented with

every root, twig, leaf and flower, with every seed, nut and berry, and

fungus, in his environment. Pharmacology is older then agriculture.

There is good reason to believe that even in Palaeolithic times, while

he was still a hunter and food gatherer, man killed his animals and

human enemies with a poisoned arrow. By the Stone Age he was systematically

poisoning himself The preserved heads of poppy in the kitchen middens

of the Swiss Lake dwellers shows how early in his history man discovered

the techniques of self-transcendence through drugs. There were dope

addicts long before there were farmers.

As an example

of the extent to which such people go, it may be mentioned that

the Jagga even developed truth serum. 40

Claude Levi-Strauss underscores

another aspect of this psychomedical contribution: 41

The West, for all its mastery

of machines, exhibits evidence of only the most elementary understanding

of the use and potential resources of that super-machine, the

human body. In this sphere on the contrary, the East and Far

East are several thousand years ahead; they have produced the

great theoretical and practical summae represented by Yoga in

India, and Chinese 'breath techniques,"' or the visceral

control of the ancient Maoris. . . .

In all matters touching on the

organization of the family, and the achievement of harmonious

relations between the family group and the social group, the

Australian aborigines, though backward in the economic sphere,

are so far ahead of the rest of mankind that, to understand the

careful and deliberate system of rules they have elaborated,

we have to use all the refinements of modern mathematics. . .

.

The Australians with an admirable

grasp of the facts, have converted this machinery into terms

of theory, and listed the main methods by which it may be produced,

with the advantages and the drawbacks attaching to each. They

have gone further than empirical observation to discover the

laws governing the system, so that it is no exaggeration to say

that they are not merely the founders of modem sociology as a

whole, but are the real innovators of measurement in the social

sciences.

40. Truth serum: referred to by Robert Lowie, Social Organization,

New York, Rinehart, 1948, p.168, 169.

41. Levi-Strauss, C., "Race and History" in the series

The Race Question in Modern Science, UNESCO, Paris, 1952,

p.27.

pg.9

of 20 pg.9

of 20

Not

all sociologists would agree with Levi-Strauss, of course, but there is

no doubt that the social aspect of human relationships have here been

subjected to unusual scrutiny. It seems almost a rule, in fact, that the

simpler the culture in its materials, the more elaborate its formalized

social structure is apt to be, including its rituals. And conversely,

the more complex the civilization, the less formal its social patterns

are likely to be. Ralph Linton speaks of one occasion in an Australian

tribe, where it happened that the regulations had become so involved that

a time came when it was found nobody could properly get married any more!

42

All the American Indians had an

extensive medical knowledge. Their surgical skill was remarkable,

and like non-Indo-Europeans in many other parts of the world,

ancient and modern, they practiced such delicate operations as

trepanation with remarkable success. 43

Such extremely delicate surgery

implies the use of some kind of anaesthetic. Robert Lowie reminds

us that we owe this very fundamental discovery to the South American

Indian. As he says, "What is absolutely certain is that

our local anaesthetics go back to the Peruvian Indian's coca

leaves, whence our cocaine."44

Another important invention from

the same source is the enema. Robert Heizer, in an issue of a

well-known publication which was devoted to the history of this

instrument, states that:45

The medical practices of the

Indians of North and South America prior to the shattering of

their cultures by Caucasian wars and exploitation, were truly

amazing in their magnitude and excellence. Our fractional knowledge

of these attainments derives from early historical records, ethno-botanical

works by botanists and pharmacologists, and from intensive study

of skeletal materials by trained observers. Included in the roster

of medical techniques was the administration of enemas and lavements

by means of a number of instruments -- bulb and piston type syringes

and clyster tubes.

42. Linton, Ralph, The Study of Man,

New York, Appleton Century, Student's Edition, 1936, p.90.

43. Popham, Robert, "Trepanation as a Rational Procedure

in Primitive Surgery," University of Toronto Medical

Journal, vol.31, no.5, Feb., 1954, p.204-211.

44. Lowie, Robert, An Introduction to Cultural Anthropology,

New York, Farrar and Rinehart, 2nd edition 1940, p.336.

45. Heizer, Robert, "The Use of the Enema by the Aboriginal

American Indians, Ciba Symposia, vol.5, Feb., 1944, p.1686,

1690 (illustration)

pg.10

of 20 pg.10

of 20

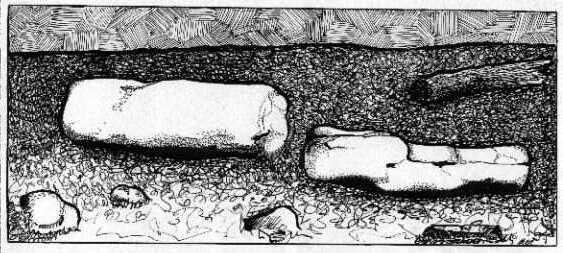

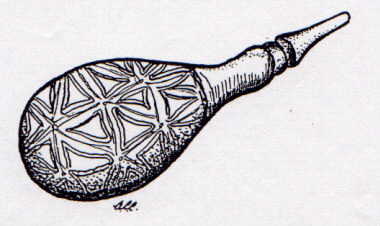

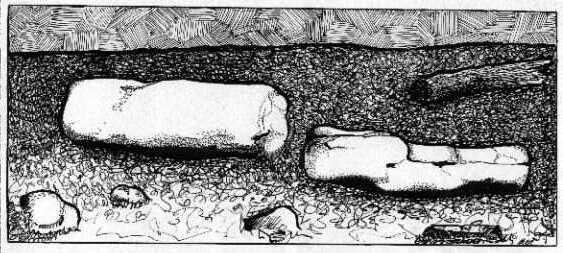

| Nordenskiold, speaking of the American Indian as an

inventor, refers to such enema syringes, one of which he illustrates.46 The illustration, Fig. 6,

is taken from his work, and shows how little we have been able

to improve upon it! Even the decorative scheme is in excellent

taste, and the mode of manufacture was copied exactly when Indo-Europeans

first began to exploit the native development of rubber latex. |

Figure 6. |

The same writer also mentions the

invention of tweezers for medical purposes for which he gives

the credit to the Araurcanians, another Peruvian tribe. The Jivaro

Indians use the pincers of living ants for the purpose of suturing

wounds -- a most extraordinary procedure that has been observed

in other parts of the world also. 47 The skin is drawn together, the small ant so applied

that it seizes the suture and holds it tightly closed in its

strong mandibles, and then the animal's body is quickly snipped

off! So the series of fine pincers along the wound hold the skin

lesions together till healing takes place. Erwin Ackernecht in

writing of this interesting technique, concludes that it is a

witness to "the great inventive power that the 'savage'

develops in all those fields that he deems worthy of interest."48

Ingenuity: its diversity

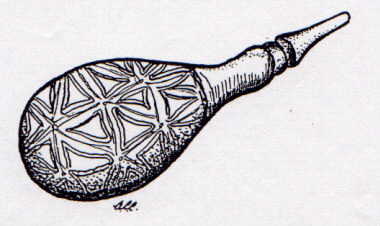

We have mentioned rubber enemas.

According to Nordenskiold, there appears to have been a secondary

development arising out of it: the making of hollow rubber balls

for games. 49 Such

balls were made by forming a core of clay or some such material

and then dipping this repeatedly in a solution of latex allowing

each coating to dry before applying the next one. When the skin

was thick enough, a small round hole was cut through the rubber

to the clay core and the latter was removed through the hole,

a small amount at a time. The hole was then plugged with another

wad of latex, in a semi-hard condition, and the whole redipped

once more in latex thus sealing the air inside the ball. Solid

balls were also made, which weighed as much as 25 pounds. These

were used in the well known games played by the Maya in such

open courts as have been found at Chichen Itza, Mexico, and elsewhere.

46. Nordenskiold, Erik, 'The American Indian

as an Inventor", Journal of the Royal Anthropological

Institute, vol.59, 1929, p.273ff.

47. Ants used for suturing: see E. A. Underwood, reviewing Lewis

Cotlow, Amazon Head Hunters (London,, Robert Gale, 1954)

in Nature, vol.175, Feb., 19, 1955, p.318.

48. Ackernecht, Erwin, in Ciba Symposia, vol.10, July-August,

1948, p.924, in a note under the title "An Ingenious Device

for Stitching Wounds." The same author has a paper entitled

"Primitive Surgery,"(American Anthropologist, New

Series vol.49, January-March, 1947), in which he gives a bibliography

on the subject of 204 references.

49. Rubber balls: this is the opinion of E. Nordenskiold, 'The

American Indian as an Inventor", Journal of the Royal

Anthropological Institute, vol.59, 1929, p.298.

pg.11

of 20 pg.11

of 20

An

article in a rubber journal recently pointed out that these balls are

only one example of the use made by the American Indian of this plastic

material 50. He also made

watertight shoes, flasks, ponchos, and dolls. The same article states

that:50

The development and use of natural

rubber by the American Indian is impressive, for in 300 years

his "civilized" conquerors made little improvement

in the ancient method of rubber manufacture.

The natives

used a certain sap of a vine (Iponoea bona-nox) or from

a liana (Catonyction speciosum) to coagulate the latex.

Certain trees have the latex in a form which is rubber in suspension

in water. The water can be evaporated and the rubber remains,

without any need for a catalyst.

The story of Charles Goodyear's

efforts to take over the development of rubber from the natives

of Brazil and exploit it in America and elsewhere, is well known.

The problem was to treat it so that it would retain its structure

even in hot weather. Their own rubber served the Indians well

enough, especially since they had the secret of curing it by

using local products as catalysts. Goodyear, again and again,

brought himself, his family, and his backers to the point of

ruin and bankruptcy because he could not cure the stuff out of

which he was trying to make raincoats, mail bags, and overshoes.

As soon as warm weather came, his products turned into a sticky

useless mess! Of course he finally discovered how to cure by

vulcanizing, using sulfur as a catalyst. 51 But it seems probable that many of his heartbreaks

never would have occurred if he had gone back to the originators

of rubber articles and asked them to teach him what they knew

first.

Moreover, it is very doubtful if

Goodyear or anyone else of his cultural background would have

seen, in the Brazilian forest, what the natives had seen, i.e.,

a natural product requiring only to be treated with another natural

product to supply a remarkably versatile and useful material.

In the matter of Textiles, we have

been borrowers in almost every detail. It is considered by G.

P. Murdock that the Central American Indian excelled here also:

52

In skill and technique in the

textile arts the ancient Peruvians have had no equal in human

history. They wove plain webs, double faced cloths, gauze and

voile, knitted and crocheted fabrics, feather work, tapestries,

fine cloths interwoven

50. Anonymous article in Rubber Age, November,

1956, p.365.

51. Charles Goodyear: see on this, H. Stafford Hatfield, The

Inventor and His World, Harmondsworth, UK, Penguin Books,

1948, p.41-44.

52. Murdock, G. P., Our Primitive Contemporaries, New

York, Macmillan, 1934, p. 428, 429

pg.12

of 20 pg.12

of 20

with gold and silver threads -- employing in

short, every technique save twilling known to the Old World, in addition

to some peculiar to themselves. . . . They employed methods identical

with those used in the famous Gobelin and Beauvais tapestries; they

nevertheless in harmony of colours, fastness of dyes, and perfection

of technique, far surpassed the finest products of Europe.

C. Langdon White

says that the best of their fabrics were from the wool of the

vicuna, softest of all animal fibres, with 270 threads to the

inch as compared with 140 threads otherwise considered to be

outstanding.53

MD.C. Crawford writing in 1948

before certain very recent developments underscores this achievement

of the Indian. He made a particular study of this aspect of their

art and skill, and concludes: 54

As a matter of fact, Europe

has never produced a single original natural textile fibre or

any dye except perhaps wool. She has not contributed a single

fundamental or original idea to the basic mechanics of textiles,

nor a single original and fundamental process of finishing, dyeing,

or printing. . . .

In the broader world history of

textiles and cloth, the ingenious English inventions of the 18th

century (led by Kay's fly-shuttle) are but incidental mechanical

modifications and developments of older ideas which grew out

of the social conditions in England, and were directly due to

the importation of cotton and silk fabrics from the Far East

during the 16th and 17th centuries. No new basic principles either

in spinning, weaving, or fabric construction, nor new methods

of decoration, dyes, colours, or designs, are involved in the

English machines. The ancient principles of twisting and elongating

masses of fibre into yarn, the principle of interlacing one set

of filaments held in place between parallel bars of a second

set of filaments, remains undisturbed. No new raw materials are

involved: flax, hemp, wool, cotton, and silk, remain the principle

fibres. And for colour the dyes of antiquity were still employed.

As a matter of fact, all the dye raw materials of antiquity,

both from Asia and America, were still mentioned In English dyer's

manuals in the late part of the 19th century, and years after

Perkins' experiments with coal tar derivatives in 1856.

Silk of course

came to us from China, felt from Mongolia, 55 materials made from pulps were developed in Polynesia

(tapa cloth, etc.). These last are coming into their own in our

day, the capacity for greater production being about our only

claim for credit. And even here, the claim may be somewhat premature,

because considerable difficulty has been experienced thus far

in the manufacture of such materials on a large scale. The native

products are hand made of course. Moreover their methods of decoration,

by tie-dyeing, batique, and silk-screen, are simply not applicable

to mass production methods at present. We do not have time for

tie-dyeing.

53.White, C. Langdon, 'Storm Clouds over the

Andes," Scientific Monthly, May, 1950, p.308.

54. Crawford, M.D.C., The Conquest of Culture, Fairchild,

New York, 1948, p.184, 185.

55. Felt: see Mabel C. Cole and Fay Cole, The Story of Man,

Chicago, Cuneo Press, 1940, p.374.

pg.13

of 20 pg.13

of 20

Moreover,

as we shall see when we come to consider the textile 'industries' of ancient

Sumeria, virtually the whole concept of mechanization, of large mills

and hundreds of specialized workers each doing a single kind of operation,

was well developed at least five thousand years ago in the Middle East.

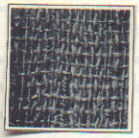

Meanwhile the Egyptians succeeded

in weaving such fine fabrics that they are still equal to our

own best products woven by the very latest mechanical means.

Some of the garments associated with King Tutankhamen's tomb

have 220 threads to the inch as shown in Fig. 7. Common handkerchiefs

today, of linen, show only about 60 to 70 threads per inch and

good linen cloth for such purposes seldom has more than 100 threads

per inch, or less than the Egyptian prototype.

a. |

b. |

c. |

These samples of fabric were taken from Tutankhamen's

tomb. They are three different pieces of material, (a) being

a dark cream color with a light filmy texture, (b) a dark brown,

almost black, with two threads one way, and one the other way,

and (c) is a dark brown of a coarser weave.

These photographs were taken with a microscope, thus emphasizing

the size of thread and concealing the fine texture of the cloth.

Magnification was 15 x. Sample (a) reveals about 220 threads

to the inch.

|

Figure 7.

Their

pottery has always been a source of amazement, whether in the

New World or the Old. Chinese pottery has long been prized

for its beauty in form, colour and texture. Central American

pottery is remarkable for its complete freedom of form, and for

its ingenuity also. In an environment where evaporation rates

are high, it is desirable to cut down the size of the opening

at the top. But this makes pouring more difficult. The air rushing

in suddenly causes the water to flow out unevenly, and to spill

easily. But in many places water is too precious to be wasted

in this way. The Peruvians and the Maya overcame this by putting

two spouts on the pot so that one became both a handle and a

separate air inlet. The variations of this theme were both ingenious

and aesthetically pleasing. Not content with this, they even

went further and so designed the passages that when water was

poured out, the air rushing in caused a whistle to blow. In some

cases it is difficult to see why this was done, unless it was

to warn the adults when the children were robbing them of a rather

precious commodity! Other types seem clearly to have been whistling

'kettles' -- a further effort to conserve waste by warning the

lady of the house that the water was boiling away. 56

Many of their vessels are shaped

as heads, faces, animals, and even whole people. And these reproductions

were not approximations. They were so lifelike in many cases

that they must surely have been actual portraits. Their artistry

and skill seem to have known no limits.

The same is true of Middle East

pottery. In Minoan Crete the wares are of such delicacy that

it seems they must be copies of originals made in hammered metal.

Even the 'rivets' are indicated sometimes. They also reveal that

the metal prototypes were sometimes formed by a process akin

to deep drawing as we technically understand it now. Some of

the pottery from the earliest levels at Tell Halaf and Susa is

astonishing in its complete freedom of form and unbelievable

delicacy. We shall refer to this subsequently.

56. Whistling kettles: on this see, T. Athol

Joyce, "Marvels of the Potter's Art: In South America"

in The Wonders of the Past, edited by Sir John Hammerton,

London, Putnam's, 1924, vol. 2, p.464, 465.

pg.14

of 20 pg.14

of 20

Ingenuity of the Incas and Mayans

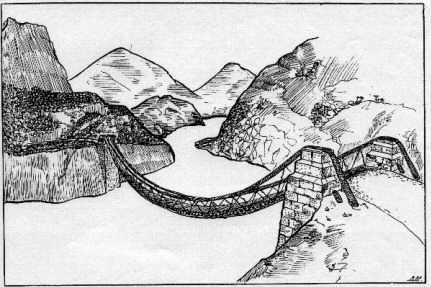

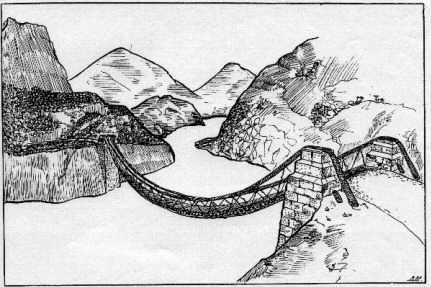

The fame of the Central American

Indians in the matter of road building has been well reported.

Cement pavements and other types of surfaced roads; suspension

bridges spanning up to 450 feet, anchored at each end by massive

stone pillars and capable of carrying cattle and pack animals,

were built in some of the most rugged country in the world. These

bridges were often 6 to 8 feet wide. The ropes by which they

supported these slender structures are known to have been up

to 12 inches in diameter. 57 One of the most famous builders was the Inca, Mayta

Capac, who is generally dated from 1195 to 1230 A.D.

Although they used

wheels on toys, for some reason they did not employ wheeled vehicles.

At least there are no remains of them, nor pictures, nor references

in their traditions or literature. Yet they did use road-rollers

weighing up to 5 tons! 58 One of these is illustrated in Fig. 8 In Fig. 9 is

shown a reconstruction of a suspension bridge. Moreover they

had extensive postal systems along these highways, and an excellent

quality of paper for writing letters and keeping records.

Figure 8. Figure

9.

Archaeologists

have discovered that the Maya were making true paper approximately

3000 years ago. 59

Before these artisans disappeared, the Aztecs had learned the

secret. This same process was handed down from generation to

generation and today is used by the Otomi Indians in Mexico.

The inner bark of the fig tree is soaked in running water until

the sap jells and can be scraped off. The fibrous residue is

then boiled in lime, washed once more, and laid on a flat wooden

surface like a bread board, where it is pounded to a pulp. The

pulp is left on the board and sun dried. The ancient Aztecs went

one step beyond the 20th century Otomis. Their process was identical

up to this point, but after the paper was dry they sized it,

then calendered it with hot stones to produce surfaces readily

adaptable for printing. They then printed on it with a crude

kind of moveable type!

Although many of these original

developments have long since been lost sight of, there still

remains sufficient on record to suggest that in Central America

a stage of technical excellence had been achieved and natural

resources exploited, mathematics developed (including the use

of zero and a place system for numbers) the development of a

literature (among the Maya at least), and a leisure class, that

the advance into Science should

57. Ropes: see Alexander Goldenweiser, Anthropology,

New York, Crofts, 1937, p.402, and Victor W. von Hagen, Realm

of the Incas, New York, New American Library, 1957, p.186,

187 for illustrations.

58. Road rollers: see Marshall H. Saville, "The Ancient

Maya Causeways of Yucatan," Antiquity, vol.9,

March, 1935, p.73.

59. Paper in South America: see Victor W. von Hagen, "The

First American Papermakers," The Paper Industry &

Paper World, December 1944, p.1133.

pg.15

of 20 pg.15

of 20

have been made. Gilbert Lewis says:

60

Probably

the most remarkable achievements of the American Indians, were

in the fields of arithmetic, astronomy, and the Calendar. Two

of the greatest inventions of arithmetic, the zero and the sign

of numerical position, were regularly employed in America long

before they are known to have occurred elsewhere. . . .

It may be noted that few apparently

unrelated items which I have discovered in the literature may,

when put together, suggest the possible use of astronomical instruments

in early America. Both in Mexico and in Peru concave mirrors

were found, articles that had not been seen in Europe at the

time of the Conquest. In Peru, these concave mirrors were employed

in a solar rite. Periodically all old fire was extinguished and

a new fire was started by the priests who, with these mirrors

focused the rays of the setting sun on a wisp of cotton. Among

the Aztecs new fire was produced at night by the fire drill.

However, that they had recollections of a practice akin to the

Peruvian is suggested by the name of one of their chief gods

"Smoking Mirror."

Speaking of

Peruvian surgery, J. Alden Mason, quoting the well known paleopathologist

R. L. Moodie, says: 61

I believe it to be correct to

state that no primitive or ancient race of people anywhere in

the world had developed such a field of surgical knowledge as

had the pre-Columbian Peruvians. Their surgical attempts are

truly amazing and include amputations, excisions, trephining,

bandaging, bone transplants (?), cauterizations and other less

evident procedures.

He then

speaks of the use of anaesthetics and possibly hypnosis. He remarks

that some skulls show the result of operations on the frontal

sinus. Their 'operating rooms' were first cleared and purified

by the sprinkling and burning of maize corn-flour, first black

and finally white.

Mason considers that it is literally

impossible to exaggerate the technical achievements of these

Peruvian highlanders in the field of textiles. He holds that

it is not the view merely of enthusiastic archaeologists, but

of textile manufacturers themselves. Their skill he terms 'incredible.'

They even had invisible mending in place of patching. The Aymara

still do! In metallurgy they were not far behind.

Among their textiles, according

to Mason, have been found "twining, plain cloth, repp, twill,

gingham, warp-faced and weft-faced or bobbin pattern weave, brocade,

tapestry, embroidery, tubular weave, pile knot, double cloth,

gauze, lace, needle-knitting, painted and resist-dye decoration

and several other special processes peculiar to

60. Lewis, Gilbert, "The Beginnings of

Civilization in America," American Anthropologist, New

Series, vol.49, January-March, 1947, p.8 and footnote.

61. Mason, J. Alden, The Ancient Civilizations of Peru, Harmondsworth,

Penguin, 1957, p.222.

pg.16

of 20 pg.16

of 20

Peru and probably impossible to

produce by mechanical means." It is even possible that they may have

watered some crops with coloured liquids to produce naturally dyed fabrics

that were indeed sun-worthy!

Nor is this inventiveness

limited to Central America, although for climatic reasons this

may have been the best environment to encourage high civilizations.

The Iroquois had invented 'rifled' arrowheads long before they

found themselves face to face with or in possession of rifled

fire arms. 62 It

does not seem likely that the spiralling is sufficient to rotate

the arrow rapidly enough that the need for feathers is eliminated.

This at least has not proved to be the case with my own sample.

Evidently such was not the objective. What is clearly achieved

is a far more serious wound. Like the outlawed dum-dum bullets

of World War I, the form of the head is such that the arrow does

not pass right through (where it could easily be withdrawn) but

buries itself in the flesh and stops there. The energy of the

arrow is absorbed as the head 'corkscrews' into the body.

The

Aymara of Peru build sailing boats and use them on lakes two

and a half miles above sea level -- yet there is scarcely a tree

to be found at this elevation. These vessels are made entirely

of local bulrushes, and even the sails are mats woven from the

same materials. The masts are built up of small pieces of wood

spliced together. Provided these vessels are permitted to dry

out every little while, they will carry a considerable load.

63

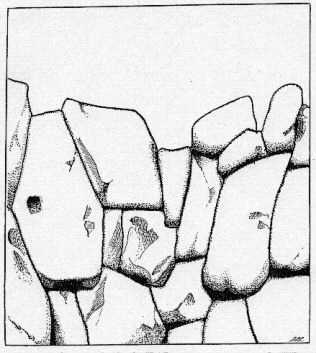

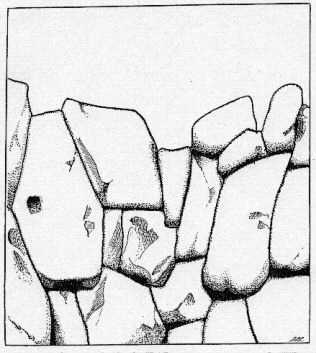

The pre-Inca

Indians were master architects, building great monuments and

immense fortifications of stones set in to each other by being

laid and lapped together right on the spot. How they were erected

is still a mystery, for many of the stones are huge. But this

certainly is the only genuinely earthquake-proof architecture

in Middle America! For an illustration of one of the most famous

such fortifications (?) see Fig. 10. |

Figure 10. |

One of the most surprising things about

the great Ball Court of Chichen Itza is its acoustical properties.

Recently the Editor of an American magazine visited this court

and reported on this unexpected feature.He wrote: 64

We climbed to the vantage

point of one of the stands for the thrones of the priests at

the southern end, while our guide went to the other. We were

five hundred feet apart. We talked in low tones no louder than

a couple would use sitting in the living room of an average

home. We could hear each other perfectly. We reduced our voices

to a mere murmur: we could still hear each other perfectly. .

. .

62. Rifled arrowheads: I have one of these

in my possession. There are several references to them in the

literature and some examples in Museums in Canada and the United

States. There may have been a family, a kind of Iroquois Krupps,

which supplied friend and foe alike -- at a price! Edward

B. Tylor refers to them (Anthropology, New York, Hill,

1904, p.155), and even earlier, Sir William Dawson,( Fossil

Men and Their Modern Representatives, London, Hodder &

Stoughton, 1883, p.124). There seems to be no doubt about their

intentional design.

63. Aymara boats: see Stewart E. McMillin, "The Heart of

Aymara Land," National Geographic Magazine, February,

1927, p.213-256.

64. Barnhouse, Donald G., "The Editor Visits Mexico's Mayan

Ruins," Eternity Magazine, May, 1956, p.35.

pg.17

of 20 pg.17

of 20

The General Electric

Company, we were told, brought a large group of engineers to Chichen

Itza to carry on acoustical experiments in the big ball court. They

attempted to duplicate the court elsewhere but did not get the same

acoustical effect because they had not built with limestone.

The tools of the pre-Columbian builders were

no less remarkable than their buildings. It is believed now that

they may have used glass cutting edges for saws, etc., in place

of steel -- the glass being a natural volcanic residue. Recent

experiments demonstrate that such tools can be most effective.

The idea is suggested by the form of certain fighting weapons.

65

They had

even developed a specialized form of dental repair, using a kind

of Portland Cement filling which has remained firm and intact

in tooth cavities for 1500 years! Of this discovery Sigvad Linne

remarks, 66

The findings (of archaeologists)

have revealed to us some of the inventiveness and technical skill

possessed by the Indians. The practical aids of these unknown

technicians may have been primitive yet it could scarcely have

been "primitive peoples of nature" that with such simple

means achieved results before which their later born Swedish

colleagues sometimes stand in dumb amazement.

This is a digression,

but one might mention that a recent report from Washington states

that there is now evidence of the habitual use of some kind of

cleaning agents on the teeth of prehistoric skulls. 67 Since the Chinese had by

at least 1500 A.D. developed a tooth brush that looks remarkably

like its modern counterpart, there is surely nothing new under

the sun! 68 For

a picture of this toothbrush, see Fig. 11.

Figure 11.

65. Glass saws: as reported in Science

News Letter, July 13, 1957, under the title "Glass-toothed

Saw Cuts Wood: An Ingenious Hand-made Tool May Provide a Solution

for an Ancient Scientific Puzzle." (Anonymous).

66. Tooth filling: see Sigvad Linne, "Technical Secrets

of American Indians," Journal of the Royal Anthropological

Institute, vol.87, Part II, July-December, 1957, pp.152,

153, 163.

67. Toothpaste: Science News Letter, Dec.23, 1956, p.390,

in a series of brief notes written anonymously under the heading

"Anthropology -Archaeology."

68. Toothbrush: see Curt Proskauer, "Oral Hygiene in the

Medieval Occident," Ciba Symposia, vol.8, Nov., 1946,

p.468. The illustration is from a woodcut in the Lei Shu Ts'ai

Hiu, a Chinese Encyclopedia.

pg.18

of 20 pg.18

of 20

Nordenskiold

adds to the credit of the America Indians the invention of the hammock

(New Guinea) 69, children's

go-carts (North-western Brazil), 70 cigar holders, 71 the chain 72 and an ingenious self-acting water-pump (Columbia) which the

Spaniards adopted and converted into a bilge pump. 73

It could become just an endless

catalogue if we were to go on listing isolated instances of native

ingenuity such as the use of the skin of the ray-fish by the

Polynesians as a 'sand paper'; 74 the use of giant fireflies called Cucuyo and

tied to the feet by the natives in the West Indies to light their

way along jungle paths at night,75 and so forth.

Conclusion

So much importance is attached

to inventors and their inventions, that they were held in great

veneration and quite often were ultimately deified. The only

encyclopaedias the Chinese had, originally, dealt with the heroic

figures who were famous because they had invented something.

76 Indeed in some

cultures, this kind of talent is so generally expected of the

males that the would-be son-in-law must win his bride by performing

some almost impossible task set by the family, which calls forth

nothing short of inventive genius! 77

Perhaps this is not such a remarkable

circumstance in a way, since we are tending to move in the same

direction and devote more and more space in encyclopaedias to

inventions. Yet scholars and generals, poets and artists, politicians

and sportsmen, still share the pages of our history books with

equal recognition.

69. Hammocks: Nordenskiold, Erik, 'The American

Indian as an Inventor", Journal of the Royal Anthropological

Institute, vol.59, 1959, p.281.

70. Go-carts: Nordenskiold, E., ibid., from North Western

Brazil.

71. Cigar holders: Nordenskiold, B., ibid., p.302.

72. Chain: Nordenskiold, E., ibid., p.302, used by a small

tribe, the Hurari. in Matto Grasso, and found nowhere else in

South America.

73. Bilge pump: Nordenskiold, E., ibid., p. 300.

74. Sandpaper: see Leonard Adam, Primitive Art, Harmondsworth,

UK, Penguin, 1949, p.162.

75. Fireflies: see Donald C. Peattie, "The Miracle of the

Firefly," The Reader's Digest, October, 1949, p.102.

76. Needham, Joseph, Science and Civilization in China,

Cambridge, UK., Cambridge University Press, 1954, vol.1, p.54.

77. Professor T. F. McIlwraith, Head of the Department of Anthropology

in the University of Toronto, gave a lecture on the various means

adopted by different people to test aspiring husbands. The Arawak

of Central Africa adopt this method, as do other widely scattered

tribes. An early chapter of Genesis (4:17-21) gives prominence

to the first city-builder, the first agriculturalist, the first

tent-dweller, the first musician, and the first metal worker.

The latter is referred to as Tubal-Cain, which some authorities

feel may be the original form of the word Vulcan, who

was (like many Chinese inventors) subsequently deified.

pg.19

of 20 pg.19

of 20

At

any rate, we can see that such an aptitude for invention, and the ability

to exploit the natural resources of the environment, was encouraged only

so far as the overall economy allowed. There was no leisure, often little

security, not much accumulation of wealth, and frequently insufficient

'sophistication' to suggest to such people that they might go further.

To a man who can hardly keep food in the larder for his family, idle curiosity

is not likely to find much encouragement. These people searched, and found

the immediate solution: but they did not have the energy, the need, the

time, or the will to re-search and extend the answers they had found once

they proved effective enough. They have searched. We re-search.

But

surely this was not true in China, or Sumeria, or Egypt or Crete,

or the Indus Valley, or in Anatolia? Why did not these much more

advanced and highly organized Cultures progress further? Why

did they not explore their own well-developed technology and

proceed to a Scientific Age? The climate was suitable, records

were extensive, and natural resources were abundant enough in

many cases.

Let us examine their achievements

and (since we have the means to do so) explore their underlying

philosophy as revealed in their literature; for, unlike cultures

so far considered, they all developed writing very early in their

history, and their educated sons left many records of their thoughts,

as well as their business documents, and their royal chronicles

of inventions and of conquests.

pg.20

of 20 pg.20

of 20  Copyright © 1988 Evelyn White. All rights

reserved

Previous Chapter Next

Chapter

Copyright © 1988 Evelyn White. All rights

reserved

Previous Chapter Next

Chapter

|