|

Abstract

Table

of Contents

Introduction

Part I

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Part II

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Part III

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Part IV

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

|

Part I: Technology: The Contribution

of Non-Indo-Europeans

Chapter IV

The Achievements of China

Finally,

we come to the great contribution made by China. If we should

ask today what three things above all have contributed to or

are contributing to our present conquest of the earth, we might

possibly agree that printed matter, a convenient medium of exchange

of some kind (i.e., paper currency), and powered propulsion are

fundamental. All of these -- and of course hundreds besides --

we have derived from China, though often indirectly via the Arab

world.

For our wheeled vehicles we initially

used draft animals domesticated in the Middle East, but because

of harnessing methods, these draft animals could not pull nearly

as much as they now do, thanks to the development in China of

far more effective systems of harness. But we have of course

long since passed out of the draft-horse age into the jet propulsion

era. The motive power for such high-speed engines was likewise

inspired by the Chinese. In the air, China and the Far East anticipated

us in virtually every form of airborne vehicle or device, including

of course rockets, but also kites, gliders, balloons, parachutes,

weather forecasting, and even the helicopter principle in the

form of toys.

Because of the extraordinary developments

of Chinese technologists, it is not uncommon to see references

to their "science." As we shall try to show this is

perhaps an error, even though some of

the greatest authorities do it. In reviewing Needham's magnum

opus on the Science and Civilization of China, the

Editor of Discovery says:145

We are forced to realize

that the old question as to why Science failed to develop in

China must be replaced by the much more cautious one, "Since

the Chinese people have shown ability to observe and invent surpassing

that of the West until comparatively recent times, what factors

in environment and thought carried them so far and yet prevented

the development of the full scientific method?"

145. Under the title "Science and Civilization

in China," in the section "The Progress of Science,"

Discovery, Nov., 1957, p.458.

pg.1

of 13 pg.1

of 13

With

all due respect to both Needham and the Editor of Discovery,

I think there is a serious danger here of supposing that

Science is merely an extension of Technology, a kind of natural

adult stage. I would rather take the view held by James Conant

that Science is not merely an extension of Technology, any more

than infinity is merely a very very large number; it is in a

different category. One should not speak of a 'full scientific

method,' any more than one should strictly speak, conversely,

of something only being 'half-alive.'

But of their engineering achievements

and mechanical and technical skill there is not the slightest

doubt. It is all the more remarkable that they did not step over

the boundary into the kind of Industrial Revolution which resulted

from the development of Science in Europe. Certainly there is

no evidence that either they, or any of the other highly developed

civilizations we have been discussing, were ever on the verge

of doing so. As Herbert Butterfield put it in his Origins

of Modern Science;146

There does not seem to be any

sign that the ancient world before its heritage had been dispersed

was moving towards anything like a scientific revolution.

The question

of why China stopped short where she did, is explored at great

length by Needham: his knowledge of Chinese culture should surely

entitle him to speak of their having achieved a measure of scientific

knowledge, if he feels it is justified to do so. And this he

does. To challenge such an authority must appear as little more

than impudence on the part of anyone whose knowledge is so completely

derived from secondary sources. Yet even Needham himself makes

admissions now and then which are tantamount to saying that he

is using the word Science to mean merely a highly developed

Technology, and nothing more. The Chinese, as he makes quite

clear, were never impractical dreamers or people likely to waste

time asking questions whose answers did not seem to be of immediate

practical value. Yet this is an essential attitude for the scientific

mind.

In reviewing Needham's work, Robert

Multhauf indicates that the conclusion to be drawn from the two

volumes published thus far, is that Chinese Technology participated

little and probably contributed little immediately to the development

of scientific thought.147 In fact, Needham himself asserts that the Chinese

worldview depended on a totally different kind of thought pattern

from that in the West. What he could

146. Butterfield, Herbert, The Origins of Modern

Science, Bell, London, 1949, p.163.

147. Multhauf, Robert, Book review, Science, vol.124,

Oct., 5, 1956, p.631.

pg.2

of 13 pg.2

of 13

have mentioned, perhaps,

is that it is not only unlike that of Western Man, but it is

exceedingly like that developed by almost all other cultures

which are non-Indo-European. In a subsequent chapter this will

be considered carefully. It is of fundamental importance and

to my mind accounts for the absence of Science not only in China

but in all other cases.

It is interesting to find

that a Chinese man writing a few years ago on this very point,

titled his Paper, "Why China has no Science." In this,

the author, Tu-Lan Fung, makes it clear that a feeling for the

essential personal-ness of Nature is what discouraged experiment: plus a conviction that the

definition of what is 'righteous' is what is 'useful' in the

immediate sense -- leading to considerable distrust of activities

of a purely intellectual or abstract character, and a feeling

of positive distaste for experimenting with Nature. Scientific

research, in the proper sense, was an im-pure waste of time that

almost amounted to sacrilege! As he put it, "to speak of

things in abstract and general terms is always dangerous."148

Ancient China's technology

But meanwhile in this chapter,

we shall review briefly their Technology. That we obtained from

China -- silk, porcelain, explosives, paper, printing with moveable

type, paper money, the magnetic compass, and mechanical water

clocks -- is so well known that the facts need little or no elaboration.

That they anticipated us in the use of gas for cooking and heating,

cast iron, flame weapons in warfare, and, as has been stated

above, the initial conquest of the air is possibly less well

known. In addition to this they initiated the use of fingerprinting

for identification purposes, chain pumps, the crossbow and a

repeating bow with 12 shots per loading, gimbal suspension systems,

the draw loom, the rotary fan and a winnnowing machine, piston

bellows, wheelbarrows, stirrups, a greatly improved harness for

draft animals that enabled them to pull almost twice as heavy

a load, deep drilling methods, and much more is even less commonly

known.

Marco Polo gives us an extensive

account of the use of paper money.149 He say it was issued in various denominations, stamped

authoritatively by the Governor of the mint, and circulated as

the only form of valid currency over a very wide geographical

area. The bills, he says, were quite remarkably strong and did

not tear easily: any which had been torn, however, or had suffered

defacement, were recalled to the mint and replaced. Strikingly

reflecting our own bills of a few years ago, they contained a

promise that they would be redeemed for certain fixed quantities

of either precious stones or precious metals upon request! Foreign

merchants could

148. Fung, Tu-Lan, "Why China has no Science, International

Journal of Ethics, 1922, p.237-263.

149. Polo, Marco, The Travels of Marco Polo, New York,

Library Publications, (undated), Chapter 24, p..37- 140.

pg.3

of 13 pg.3

of 13

not sell their jewels

or precious metals on the open market, but were required to turn

them in at the Mint, where they received a good recompense in

paper money.

Consider how great such an innovation

really was. As Marco Polo says, a man who wished to move could

turn in hundreds of pounds (by weight) of valuable goods in personal

property, and walk away with a pocketful of money so light as

to be hardly noticeable with which in some other part of the

Empire he could recover his hundreds of pounds of goods. Everywhere

else in the world men were loaded down with the weight of their

possessions which often took such a form as to be virtually worthless

once the owner left his own locality. What such a scheme did

for trade and commerce is incalculable. What paper money does

for us today whether in notes or cheques, is virtually to keep

our civilization running. Maybe, we would have come to it anyway

in time. Certainly we did not initiate the idea. It originated

in the 13th century with the Great Khan.

It was, as Needham points out,

often many centuries before such inventions reached the West

from China. And he also notes that China received from the West

very little in return: actually, only four items are listed --

the screw principle, a force pump for liquids, the crankshaft,

and clockwork powered by a spring.150 Of these in turn, only the screw principle and an

alternative form of it (the windmill) seem actually to be to

the credit of Indo-Europeans, possibly the Greeks for the screw

and the Persians for the windmill. There is evidence that even

the screw was obtained from Egypt. Needham points out that the

art of drilling deep wells or bore-holes as used today in exploiting

oil reserves is specifically of Chinese origin.151 He also mentions that the use of graticules on maps

to simplify the specifying and location of places, is probably

of Chinese origin, although Ptolemy also employed this method.152 For almost all Needham's

illustrations, one thing can be said, to use his own words:153

Firm evidence for their use

in China antedates and sometimes long antedates, the best evidence

for their appearance in any other part of the world. . . .

150. Needham J.M., Science and Civilization

in China, Cambridge University Press, vol.1, p.241. But there

is some question about the Screw Principle, Archimedes may have

'borrowed' it from Egypt.

151. Needham, J.M., ibid., vol.1, p.244.

152. Needham, J.M., ibid., vol.1, p.245

153. Needham, J.M., ibid., vol.1, p.241.

pg.4

of 13 pg.4

of 13

He

then quotes Toynbee as having said:

However far

it may or may not be possible to trace back our Western mechanical

trend towards the origins of our Western history, there is no

doubt that a mechanical penchant is as characteristic of the

Western civilization as an aesthetic penchant was of the Hellenic.

. . .

Of this observation,

Needham says, "It is to be feared that all such valuations

are built on insecure foundations." The fact is, we simply

do not have any such penchant if we judge our 'racial' character

by looking at our achievements prior to the time we began to

borrow from non-Indo-Europeans. Since that time, racial mixture

has taken place on such a scale, and with it of course 'cultural'

mixture also, that it is difficult to say for certain who is

and who is not Indo-European in many cases. About all we can

do is to attempt to gain a certain measure of objectivity in

this regard by looking more carefully at the actual achievement

involved in many borrowed elements of our civilization which

we now think simple and obvious, merely because we have become

so used to them.

Take as an example,

the preparation of silk. Sarton says of this:154

Consider what the invention

implied -- the domestication of an insect, the 'education' of

silkworms, the cultivation of the white mulberry, the whole of

sericulture!

But -- which

is more -- it involved the recognition of the possibilities

of the material in the first place. Spider web is one of the

strongest known natural filament, but it does not seem that anyone

ever thought of cultivating spider web for this purpose. The

idea of such a possibility is not enough. It requires considerable

energy to turn it into a working industry, and although it seems

highly improbable that it was done in a single step, somebody

must have been alive to the practical advantages of making the

effort -- and have demonstrated it could be done. But then it

seems, having developed the 'industry' until it was producing

results, there it was left . . . with virtually no effort to

extend it or improve the technique or seek for substitute insects

or even attempt to make a

154. Sarton, George, A History of Science, Harvard

University Press, 1952, p.5, footnote 4.

pg.5

of 13 pg.5

of 13

synthetic material using the same

kind of substance produced by other means. This is the kind of thing we

are good at: but we always seem to need the initial stimulation from somewhere

else.

Warfare and the conquest of the air

Needham also draws attention to

the fact that the Chinese have excelled in the art of war, inventing

new weapons and new methods of attack or defence. The repeating

or magazine' crossbow, of which an example of the mechanism is

to be found in the Royal Ontario Museum, is surely the world's

first machine gun.155

To their credit (?) must also be given the invention of flame

weapons and smoke bombs. Although the former appeared in the

Mediterranean area first from North Africa, being used there

against the Romans, there is no doubt that the Arabs derived

them from the Chinese, for they called them "Darts of China."

In a classified document on Chemical Warfare published some years

ago in the United States, Harold Lamb had this to say:156

A search through Oriental

annals reveals other ancestors of present European weapons. But

it is a little surprising to find the modern hand grenade, flame-thrower,

and cannon in use in Asia centuries ago.

In Roman days vases filled

with a fire compound were employed by the Persians at the Siege

of Petra. This compound was sulphur, asphalt, and naphtha; and

the vases were cast by mangonels (a kind of giant catapult).

The flames which sprang up when the vessel broke could not be

extinguished. This was the origin of the much talked about Greek

fire, which they, having borrowed it from the Arabs . . . were

surprised to find would continue to burn on water, a fact which

mystified the early Crusaders.

Haram al-Raschid used a sulphur-naphtha

compound at the siege of Heraclea. . . . At the siege of Acre,

a Damascus engineer destroyed the wooden towers of the Crusaders

by casting against them light clay vessels of the fluid until

everything was well saturated. Then a flaming ball was thrown

out and, as we read in one old Chronicle, "all was destroyed

by flame, man, weapons, and all." During the 13th century

flame weapons were highly developed by the Arabs. They had hand

grenades -- small glass or clay jars that ignited when they broke;

and a curious fire-mace, that was to be broken over the head

of a foe, its owner keeping well to windward!

Flame throwers appeared in the

form of portable tubes that could burn a man to ash at 30 feet

[We still cannot do much better - or worse - with modern weapons!

ACC] Some of the names of these flame weapons,

such as "The Chinese Flower" and so on, only indicate

that they had their origin in that country. In fact we find the

Chinese of the 13th century very familiar with destructive fire.

They had the pao that belched flaming power, and the fie-ho-tsing,

the "spear of fire that flies."

155. Repeating Bow: this is described in the

Bulletin of the Royal Ontario Museum of Archaeology, No.10,

May, 1931, p.11, under the title Crossbow.

156. Lamb, Harold, "Flame Weapons," Chemical Warfare

Magazine, Edgewood, (U.S.), Dec., 1927, p.237.

pg.6

of 13 pg.6

of 13

It

seems then that the Arabs borrowed much from the Far East -- paint brushes

(but with the original pig bristles replaced by camel hair -- for religious

reasons), paper manufacture, block printing, silk, alchemy, and of course

such weapons of war as the above in addition to explosives. They were

great carriers but apparently somewhat uninventive except possibly during

one short period of their history. Further reference to this point will

be made in the next chapter.

Another document prepared by the

Office of the Chief of the Chemical Warfare Service (Washington,

1939) opens with these words:157

Ghengis Khan, famous ruler

of the Mongols and of China, used chemicals in the form of huge

balls of pitch and sulphur shot over the walls of besieged towns

to produce a combination of screening smoke, choking sulphur

fumes, and incendiary effects as a standard routine of attack.

Even 'irritating'

gases were used by the Arabs against the Roman Legions in North

Africa as early as 220 A.D. According to Captain A. Maude,

the secret of this weapon was learned by the Romans finally by

the capture of a Prince of Mauritania named Juball, subsequently

married to Selene, the daughter of Cleopatra.158

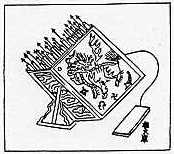

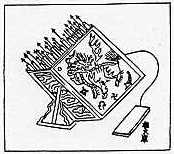

The Chinese, curiously enough did

not make much use of their explosives in warfare by developing

cannon until the idea was suggested to them by Europeans! But

they did make rocket arrows, and their launching devices were

certainly the sires of modern multiple rocket launchers. Some

illustrations of these, from a Chinese manuscript, are given

in Fig. 22, and in Fig. 23 is a single rocket weapon that

might well deter anyone! They also developed 'psychological'

weapons using large arrows with whistling or 'screaming' heads

on them that were guaranteed to stampede horses. Some of their

bows were so beautifully designed that, as Klopsteg has shown,

they could actually shoot up to half a mile with them.159

|

|

|

| The Chinese may have used

rockets as early as 1232. Here incendiary rocket arrows are launched

from baskets. |

Launcher built by the Chinese had

a capacity of 100 rocket arrows. It could be tilted to alter

its range. |

Portable launcher had a capacity

of 40 rocket arrows. These rockets had a range of some 400 feet. |

Fig. 22

157. "The Story of Chemical Warfare"

(no author stated), Jan., 1939, p.1.

158. Maude, A., "Ancient Chemical Warfare," Journal

of Royal Army Medical Corps, vol.62, 1934, p.141.

159. Klopsteg, Paul E., Turkish Archery and the Composite

Bow, privately published in Toronto, 2nd. edition, 1947.

pg.7

of 13 pg.7

of 13

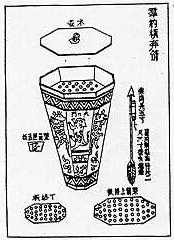

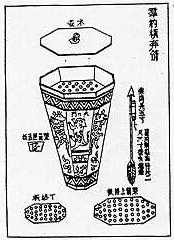

| Their gunpowder burned rather slowly and unevenly.

Hence it was not too effective in cannon. But this did not deter

them. They made use of the fact. Practically speaking,

they arranged the cannon's barrel so that it was free to move

and then fastened the charge in it so that it stayed with the

weapon, thus they had a jet propelled rocket. They then made

the tube out of tightly wound paper to save weight, and put a

point on it for better flight. But they soon found that because

of the uneven burning of the propellant the rocket's flight was

somewhat erratic. This they overcame by putting a trailing stick

on it to steady it. At first this stick had feathers, but they

found that the feathers were simply burned off. It made no difference,

for these feathers proved unnecessary. What they did discover

was that regardless of the size of the rocket, it had the best

balanced flight when the stock was seven times as long as the

rocket head. This is still found to be so.160 |

Fig. 23 A Chinese rocket weapon. |

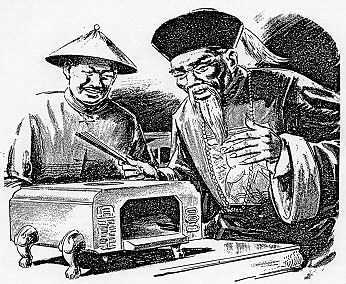

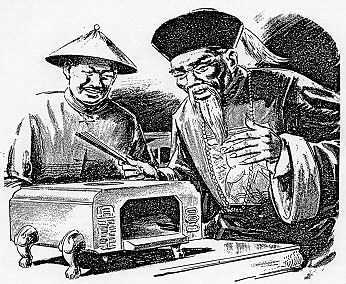

Fig. 24 An illustration of the earliest known Cast

Iron Stove from China as published in an advertisement by the

Borg-Warner Corporation, in the Saturday Evening Post, of Sept.

8, 1951. |

Willey

Ley says that the Arabs learned of these weapons from the Chinese

and thus called them "Alsichem alkhatai" or Chinese

Arrows.161 The

French Sinologist, Stanislas Julien, has found references to

these rockets in China as early as 1232 A.D.

In metallurgy (and in alchemy),

the Chinese were far ahead of the West very early in their history.

R. J. Forbes, a foremost authority on metallurgy in antiquity,

tells us that they were making cast iron stoves by 150 B.C.

at least.162 A

picture of one such stove is given for interest's sake, though

the original source of the illustration cannot be vouched for.

It was used by the Borg-Warner Corporation in an advertisement

in a Technical paper (Fig.24). |

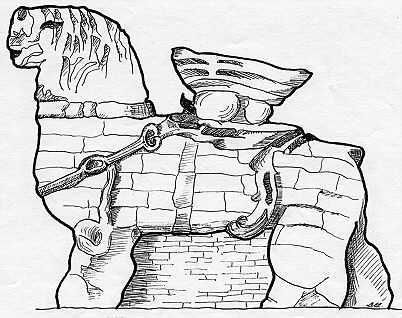

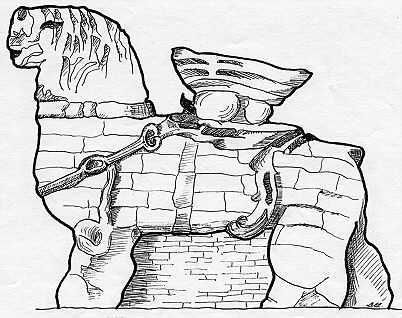

Another metallurgical journal gives

a picture of a huge single cast iron statue which is believed

to have been set up in 953 A.D. This is held to be one

of the largest single iron castings ever made. It is shown in

Fig.25

As a matter of interest, it is

sometimes pointed out that the Hittites (possibly a non-Indo-European

people with an Indo-European aristocracy) who disappeared from

History so completely that their very existence was once doubted,

are referred to in cuneiform documents as the Khittai, and sometimes

as the Khattai. C. R. Conder suggested that they disappeared

because when their Kingdom came to an end, the people packed

up and travelled East where they left their name associated with

China and the Far East in the form 'Cathay'.163

160. Coggins, Jack, and Fletcher Pratt,

Rockets, Jets, Guided Missiles and Space Ships, New York,

Random House, 1951, p.4, with foreword by WiIley Ley.

161. Ley, Willey, "Rockets," Scientific American,

Mar., 1949, p.31.

162. Forbes, R.J., Metallurgy in Antiquity, Leiden,

Netherlands, Brill, 1950, p.442.

163. Conder, C.R., "The Canaanites" " Transactions

of the Victoria Institute, vol.24, 1890, p.51.

pg.8

of 13 pg.8

of 13

|

The Arabs term Chinese Arrows as Alkhatai,

as we have seen. Forbes holds that the Hittites discovered cast

iron even before the Chinese did. If this is true, it would suggest

that this is possibly where the latter obtained their knowledge

of it.

In the conquest of the air, China

played a very prior part. Francis R. Miller states that:164

China enters first claim to

the invention of the balloon -- centuries before Europe knew

it. The Chinese further claim to have had a system of signals

by which different toned trumpets sounded from the top of high

hills and gave notice of impending changes of wind and weather,

for use by navigators of dirigible balloons.

|

Fig. 25 Cast probably in 953 A.D., this may well

be the largest single cast iron figure in the world. It stands

in the yard of the Kai-Yuam Monastery in Ts'ang-chow. It is approximately

20 feet high. |

Miller

gives an illustration from an official Chinese document of a

large dirigible said to have been used at the coronation of the

Emperor Fo-Kien, in 1306. It was large enough to carry 9 individual

gondolas which were lowered to the ground with pulley systems.

In another place Miller reports

that:165

A contemporary of Confucius

(c. 550 B.C.) named Lu Pan, who was known as "the mechanician

of Lu,"is said to have made a glider in the form of a magpie

from wood and bamboo which he caused to fly.

Miller also

states that kites, as precursors of airplanes, first appeared

in Chinese annals at a very early date. Chinese scholars who

kept records frequently refer to them. The earliest kites were

used for military signalling, first recorded in warfare in the

time of Han Sin, who died in 198 B.C., one of the Three Heroes

who assisted in founding the Han Dynasty. General Han Sin, plotting

to tunnel into Wei-yang palace, flew a kite to measure the distance

to it.166

According to Needham:167

De Ia Loubere saw the

parachute used by acrobats in Siam around 1688, and his description

was read a century later by Lenormant, who then made some successful

experiments and introduced the device to Montgolfier. This is

not to deny that the idea of the parachute had been proposed

in Europe at the time of the Renaissance, but there are Asian

references to it much earlier still.

164. Miller, Francis T., The World

in the Air, New York, Putnam's, 1930, vol.1, p.99.

165. Miller, Francis T., ibid, p.56.

166. Miller, Francis T., ibid, p.73.

167. Needham, J., Science and Civilization in China,

Cambridge University Press, 1954, vol.1, p.231.

pg.9

of 13 pg.9

of 13

More invention 'firsts'

The first

suspension bridges with iron chains were constructed in China

at least 10 centuries or more before they were known and built

in Europe.168

The story of printing and of paper

manufacture is so well known as to need little consideration

here. It came to Europe first with the old camel silk trains

as a finished product -- its secret of manufacture jealously

guarded. Not until an Arab armed victory over the Chinese armies

near Samarkand in 751 A.D. did paper settle in the West as an

industry, set up by captured Chinese paper makers. Its use soon

spread all over Europe.

The development of printing depended

upon the manufacture of suitable ink. We have already mentioned

the use of carbon black to strengthen rubber. This material was

first made by the Chinese who prepared it by burning oil and

allowing the flame to impinge on a small porcelain cone, from

which the deposited carbon was removed at frequent intervals

with a feather. The famous stick ink resulted from the compounding

of this with a strong glue solution.169

R. H. Clapperton has shown that

the recent researches of Sir Aurel Stein and Sven Hedin prove

beyond doubt that the Chinese were .not only the inventors of

rag paper, raw fibre (mulberry bark and bamboo paper) and paper

made of a combination of raw fibre and rags, but also the inventors

of loading and coating paper!170 We formerly used a china-coated paper to obtain the

best reproduction of photographs with a fine screen, though this

has now been replaced with less expensive and possibly more durable

plastic coatings. But the idea originated with the Chinese.

A recent Chinese author, Li Ch'iao-p'ing

points out that Chinese inventions opened up new fields of chemical

manufacture in early times, but then remained stationary for

centuries. One of their earlier contributions to medicine was

the extraction of ephedrine from the herb Ephedra, a process

credited to a very famous Emperor Shen Nung, who is supposed

to have lived somewhere between 3000 and 2200 B.C.171

A two thousand year old rig for

drilling salt wells was recently cited as a good model still

for the modern cable rig of today's oil fields.172

Even in the design of clothing,

they seemed to have a genius for hitting upon the best end-results,

quite apart

168. Needham, J., ibid., vol.1, p.231.

169. Stick ink: Stern, H. J., Rubber: Natural and Synthetic,

London, Maclaren, 1954, p.118.

170. Clapperton, R. H. and William Henderson, Modern Paper

Making, Oxford, Blackwells, 2nd.edition, revised, 1941, 376

pages.

171. Ephedrine: Bender, George A., "Pharmacy in Ancient

China" in the series, A History of Pharmacy in Lectures,

Parke Davis Pharmaceutical Co., 1957.

172. Oil rig model: see Edward Farber, reviewing Li Ch'iao-p'ing,,

The Chemical Arts of Old China in Scientific Monthly,

vol.68, June, 1949, p.430.

pg.10

of 13 pg.10

of 13

from the actual materials they

developed. Thus it has been recently shown that the so-called 'Chinese

sleeve' which permits each forearm to be inserted into the opposite sleeve,

is more effective for keeping the hands warm in cold weather than either

Arctic mittens, or a muff! Europeans adopted muffs and mittens -- but

having investigated the Chinese pattern thoroughly, it now appears to

be equally if not more effective. 173

Although the 'clockwork' motor

principle was taken to the Chinese from the West, their water

clocks long antedated the European systems of keeping accurate

time, and were certainly more dependable, especially when mercury

was used in place of water. The complexity of these water-clocks

has only recently been recognized as a result of the finding

of some ancient documents sufficiently explicit and detailed

to enable Needham and some associates to draw plans and diagrams

of their operation. This was reported recently in the British

Journal Nature.174 These devices were highly ingenious, involving gear

trains of several kinds, the speed being very exactly regulated

by a most dependable and clever use of water or mercury. Knowledge

of these seems to have come into Europe possibly during the Crusades.

The clocks were connected with astronomical observations, in

an endeavour to predict seasons, etc., more exactly. The interest

was purely of a practical nature.

As we have already mentioned briefly,

the Chinese had already discovered the uniqueness of finger prints,

and quickly perceived how useful this could be for identification

purposes. They were used during the T'ang dynasty as early as

618 A.D.175

According to a special report on

the uses of natural gas, it is said that the Chinese were the

first to use it. 176 Probably

the Sumerians can dispute this claim. But the story goes that

some villagers near Peiping were trying to put out a local brush

fire, when they found one flame that could not be extinguished

with water. "The practical villagers then built a bamboo

pipeline, from the outlet to the village, and used the gas for

heating brine to make salt." This is said to have taken

place somewhere about 450 B.C. Whether they can be said

to have 'invented' the use of natural gas or not is a questionable

point -- but certainly they were very quick to see its practical

possibilities. This is in exact contrast to the Romans who produced

Cast Iron in considerable quantities but threw it

173. This is reported in an Annual Project

Report issued by the US. Quartermaster Stores, Jan.-Dec.,

1956, vol.1, p.401.

174. Needham, Joseph, Wang Ling, and Derek J. Price, "Chinese

Astronomical Clockwork," Nature, vol.177, March 31,

1956, p.600, 601.

175. Haddon, Alfred C., The History of Anthropology,

London, Watts, 1934, p.33.

176. Reported in The Telegram, Toronto, April 4,

1955, in a special section devoted to the use of Natural Gas;

under the title "Gas and Pipeline too: way back in 450 B.C."

pg.11

of 13 pg.11

of 13

all away because they did not recognize

it as a potentially useful product.177 As we

have already remarked, the basic technology of all metallurgy is entirely

non-Indo-European, even heat-treatment and case hardening being known

before we 'discovered' it.

Indeed, in some instances, we not

only never have improved upon the products of our instructors,

but actually have not even been able to improve upon their methods

of manufacture, where we usually shine. Cire perdu casting

is still employed for small bronze statues of racing horses and

such items, and even the use of cow manure for the mold has been

retained from the most ancient times, to give the best results.

This system is extraordinarily effective for casting hollow articles

of intricate form, where the use of ordinary cores is quite impossible,

and yet it is found in every primitive society that has any knowledge

of metals, in every archaeological site bearing the remains of

cultures who had developed metal casting skills, and virtually

every high civilization, with the exception of Indo-Europeans,

seem to have had knowledge of the art . . . almost exactly as

it is done in Europe today. We therefore use the same basic methods

as non-Indo-Europeans for casting hollow objects in metal as

they used, just as we have adopted exactly the same method of

moulding hollow objects in rubber (cored or slush-moulded) as

the natives of Central and South America did.

Conclusions

Certain other

contributions to our technology, notably in connection with the

use of electricity and internal combustion engines, will be acknowledged

in the next chapter. They will be used to illustrate some important

aspects of this question as to whose contribution has been most

important.

Although it will be possible to

quote authorities who do not hesitate to say in so many words

that we have invented virtually nothing, such sweeping generalizations

need qualification. In the first place radical mixture has proceeded

so extensively in Europe and America that it is no longer possible

in many cases to say, for certain, which individuals do or do

not carry some non-Indo-European genes. In other words it is

no longer always clear who is truly Indo-European and who is

not. But it is true to say that whatever inventiveness we have

shown in the past three or four centuries has almost always resulted

from stimulation from non-Indo-Europeans. Our chief

177. Forbes, R. J., Metallurgy in Antiquity,

Leiden, Netherlands, Brill, 1950, p.407.

pg.12

of 13 pg.12

of 13

glory has been the ability to improve

upon and perfect the inventions of others, often to such an extent that

they appear to be original developments in their own right. We can also

make some claim to have greatly advanced mass production methods. But

it would surely be a great mistake to credit the improver with greater

inventive ability than the originator. Moreover, the individual who tells

the truth 99% of the time, but now and then tells lies, would hardly be

termed a liar. By the same token, it does not seem proper to call a people

'inventive' who once in a while do invent something, but who 99% of the

time merely adapt the inventions of others to new ends.

Paul Herrmann has written an interpretative

survey of man's conquest of the earth's surface from Palaeolithic

times to the present day. It is the work of one man, no small

undertaking, and has therefore not the comprehensiveness one

might desire, but it has the advantage of being a unified treatment.

In his foreword he has this to say: 178

A further aim in writing this

book was to weaken the very widespread conviction that our progress

in the technological aspects of civilization represents, in any

real sense, a greater achievement than that of our forebears.

The liberation of atomic energy probably means no less than did

the invention of the fire drill or the wheel in their day. Both

discoveries were of immense importance to early man.

Needham says

that the only Persian invention of first rank was the windmill,

and apart from the rotary quern whose history is not quite certain,

the only European contribution of value, mechanically speaking,

is the pot-chain pump. 179 This gives us two claims to originality. Compared

with the originality of other cultures prior, let us say, to

the 15th century A.D., we certainly did not shine in this direction.

Yet we have advanced technology so far ahead of all previous

civilizations that there must be some more subtle reason which

will bear investigation.

It could be argued that primitive

people do not invent much either: but this is easily accounted

for. They do not see any need to do so. When that need arises,

they are ingenious enough, though for reasons we may consider

subsequently, they actually resist innovations as a rule.

The next chapter will be devoted

to an examination of two things. First, the evidence for this

lack of originality among Indo-Europeans; and secondly, the evidence

for the almost total lack among non-Indo-Europeans of that "impulse

towards philosophical speculation" as Maritain so aptly

put it, 180

which has finally given us the great

technical superiority we currently enjoy over other cultures.

178. Herrmann, Paul, Conquest by

Man, New York, Harper, 1954, p.xxi, xxii.

179. Needham, Joseph, Science and Civilization in China,

Cambridge University Press, 1954, vol.1, p. 240.

180. Maritain, Jacques, An Introduction to Philosophy,

translated by E. I. Watkin, New York, Sheed and Ward, 1937,

p.26.

pg.13

of 13 pg.13

of 13  Copyright © 1988 Evelyn White. All rights

reserved

Previous Chapter Next

Chapter (Part II)

Copyright © 1988 Evelyn White. All rights

reserved

Previous Chapter Next

Chapter (Part II)

|