|

Abstract

Table

of Contents

Introduction

Part I

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Part II

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Part III

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Part IV

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

|

Part I: Technology: the Non-Indo-European

Contribution

Chapter III

Ancient High Civilizations

There

is little doubt that the basic culture in Sumeria (and later

on, in Babylonia and Assyria), in Egypt, and in the Indus Valley,

in Northern Syria and in Crete, were all non-Indo-European. The

Indo-Europeans were m fact not the creators of the cultures

they subsequently became so indebted to, but rather -- as Vere

Gordon Childe put it 78

-- the destroyers. Certainly this was true in the Indus

Valley where they are first known from history as an organized

body. China makes her great contribution to Indo-European Culture

somewhat later, and can therefore be considered last.

The basic elements of Mesopotamian

civilization in later times when the Babylonians and Assyrians

(both Semitic in origin) had achieved ascendancy, were still

essentially Sumerian. It is pretty well agreed that these Sumerians

were not Semites, being clean shaven and comparatively hairless

like the Egyptians. And from their language it is quite clear

that they were not Indo-European either. Their civilization developed

very rapidly and achieved a remarkable level of technical competence.

In the earliest stages of their history, they seem to have shared

many features with the Indus Valley people who were later overwhelmed

by the Aryans, and with the first settlers in Northern Syria,

and even with the earliest Egyptians. As further development

took place in each of these areas, cultural similarities became

obscured.

All these cultures seem to spring

into being already remarkably well organized, with skills in

weaving and pottery making, and in the erection of defensive

structures and temple buildings, and with some use of metals

from the first. It is assumed that the Sumerians were organized

into city-states before the Egyptians were, although it was once

held that the oldest centre of civilization was along the Valley

of the Nile. While there is, as yet, no evidence of the Sumerians

without the basic elements of civilization it is believed that

they came from

78. Childe, Vere Gordon, "India and the

West Before Darius," .Antiquity, vol.13, no.49, March,

1939, p.15.

pg.1

of 19 pg.1

of 19

the North and East, and

it is expected that the origins of these people (and of the Egyptians

and Indus Valley people also) will in due time be discovered

in the general direction of Jarmo, Sialk, etc. What is now fairly

clearly established is that civilization -- the arts and trades

and organized city life, with the division of labour, social

stratification, a leisure class, written records, and so forth

-- began, in so far as the Middle East is concerned, with the

Sumerians.

Vere Gordon Chide put it this way:

79

On the Nile and in Mesopotamia

the clear light of written history illuminates our path for fully

50 centuries; and looking down that vista we already descry

at its farther end ordered government, urban life, writing and

conscious art. The greatest moments -- that revolution whereby

man ceased to be purely parasitic and, with the adoption of agriculture

and stock raising, became a creator emancipated from the whims

of his environment, and then the discovery of metals and the

realization of their properties, have indeed been passed before

the curtain rises.

And T. J. Meek

confirms this by saying: 80

The Sumerian Culture springs into view ready made, and there

is as yet no knowledge of the Sumerians as savages; when we find

them in the 4th millennium B.C., they are already civilized highly.

They are already using metals, and living in great and prosperous

cities.

This is not

a study of archaeology strictly speaking, and one cannot therefore

digress into elaborate descriptions of the results of excavation

in the Middle East. It can however be safely stated -- because

easily defended -- that the most surprising aspect of the whole

venture has been the discovery that technical skill seems to

have been remarkably high from the very beginning and to have

been applied in the fields of metallurgy, building, weaving,

agriculture, medicine, art, pottery and ceramics, and transport

(both on land and water) from the earliest times. In fact succeeding

ages did not reach the same high standards as a rule. The problems

of design, basic materials, methods of production in 'quantity,'

control of quality, marketing and cost accounting -- all these

aspects were successfully dealt with in ways that have been very

little improved upon since.

79. Childe, Vere Gordon, New Light on the

Most Ancient East, New York, Kegan Paul, 1935, p.2.

80. Meek, T. J., in a lecture given in the Orientals Department,

University of Toronto, ON, FaIl, 1936.

pg.2

of 19 pg.2

of 19

A

quotation from Abbott Payson Usher seems appropriate here: 81

In

this connection it may be well to emphasize the fact that there

is no direct connection between the character of the tools and

mechanisms used and the quality of the craftsmanship. The highest

quality of work has been done with the simplest appliances. Ancient

gem cutting was, on the whole, superior to the modern work. So,

too, periods of technologic advance are not necessarily periods

of improvement, in the style or finish of the work. Many of the

misconceptions of the technique of antiquity are due to the naive

assumption that good work implies elaborate tools and mechanisms

More frequently, technologic

advances merely reduce costs and open up possibilities of a larger

volume of production.

Sumerian Civilization

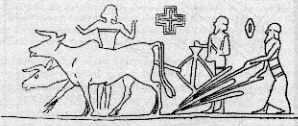

The

Sumerians knew what percentages of metals to use to achieve the

best alloys, casting a bronze with 9 to 10% of tin exactly as

we find best today; their pottery was often paper-thin, tastefully

shaped and decorated, and with a ring like true china, evidently

having been fired in controlled-atmosphere ovens at quite high

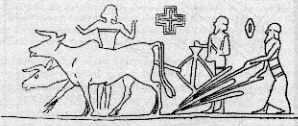

temperatures. Their methods of production led very early to a

measure of automation including powered agricultural equipment

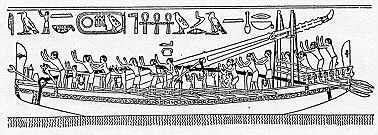

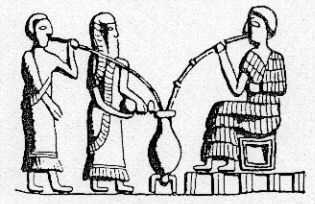

that was in the strictest sense 'mechanical' (Fig. 12).

The control of quality production was

early established by systems of inspection in their factories;

were highly organized, and price controls and wage controls were

established by law. They developed loan and banking companies

where interest rates were outlandish, yet still legally controlled;

their record keeping and postal systems were highly efficient,

mail being carried in envelopes! |

This seal impression is identified by Prof. A. Clay as UPMP

II 66, University of Pennsylvania Museum Publications. It is

interpreted by him as a plow. That it is in reality a mechanical

seeder seems clear from the hopper, and the three 'drills.'

Figure 12.

|

In addition the upper classes lived

quite sumptuously, well supplied in many cases with home comforts

and 'all modern conveniences' -- including running water in some

cases, tiled baths, proper disposal of sewage, extensive medical

care, and so forth Even libraries existed, and well organized

schools of course. By comparison their descendants did not sustain

their inheritance, but came to live in that filthy squalor, precarious

poverty and constant threat of disease, which misled earlier

generations of Europeans to suppose mistakenly that they themselves

were the creators of the superior civilization they were enjoying.

The greatness of Egypt today is

'monumental.' Sumerians did not build with stone, for they did

not have it

81. Usher, Abbott Payson, A History of

Mechanical Inventions, Cambridge, MA, Harvard University

Press, 1954, p.154.

pg.3

of 19 pg.3

of 19

in sufficient quantity.

They left another kind of monument -- imperishable written records.

Once these began to be deciphered something of their achievement

became apparent. It is by such means that we know for example

of their mathematics. Dr. T. J. Meek tells us that: 82

Like the Egyptians the

early Sumerian used the additive method to multiply and divide,

but before 2000 B.C. they had evolved multiplication tables and

tables of reciprocals and of squares and cubes, and other powers,

and of square and cube root and the like. They had attained a

complete mastery of fractional quantities and had developed a

very exact terminology in mathematics. The correct value of Pi,

and the correct geometrical formula for calculating the area

of rectangles was known before 3000 B.C. and in the years

that followed came the knowledge of how to find the area of triangles

and circles, and irregular quadrangles, polygons, and truncated

pyramids; also cones and the like. By 2000 B.C. the theorem attributed

to Pythagoras was familiar and they could solve problems involving

equations with 2, 3, and 4 unknowns.

According to one of

the best authorities in this area, they even had developed an

equivalent to our logarithm tables! 83

George Sarton,

writing some 20 years later than Meek, could add to this accomplishment

their knowledge that the angle in a semi-circle is a right-angle,

that they could measure the volume of a rectangular parallelepiped,

of a circular cylinder, of the frustum of a cone, and of a square

pyramid. He sums up the achievement thus: 84

The Sumerians

and their Babylonian successors left three legacies, the importance

of which cannot be exaggerated: 1) the position concept in numeration

-- this was imperfect because of the absence of zero: 2) the

extension of the numerical scale to sub-multiples of the unit

as well as to the multiples -- this was lost and was not revived

until 15785 A.D. with reference to decimal numbers, and, 3) the

use of the same base for numbers and metrology -- this too was

lost, and not revived till the foundation of the metric system

in 1795.

82. Meek, T. J., "Magic Spades in Mesopotamia",

University of Toronto Quarterly, vol.7, 1938, p.243. 244.

83. Neugebauer, Otto and A. Sachs, Mathematical and Cuneiform

Texts, New Haven, Yale University Press, (for the American

Oriental Society and the American School of Oriental Research),

1946, p.35

84. Sarton, George, A History of Science, Cambridge, MA,

Harvard University Press, 1952, pp.73, 74, 99 and 118.

pg.4

of 19 pg.4

of 19

Later,

he writes of what we borrowed indirectly from this source:

Many other traces can

be detected in other cultures, even that of our own today --

sexagesimal fractions, sexagesimal divisions of the hours, degrees,

and minutes, division of the whole day into equal hours, metrical

system, position concept in writing of numbers, astronomic tables.

We owe to them the beginnings of algebra, of cartography, and

of chemistry.

But perhaps

the greatest surprise of all is to find that the Greeks did not

do so very well transmitting this heritage usefully! Thus Sarton

concludes:

The Greeks

inherited the sexagesimal system from the Sumerians but mixed

it up with the decimal system, using the former only for sub-multiples

of the unit, and the latter for multiples, and thus they spoiled

both systems and started a disgraceful confusion of which we

are still the victims. They abandoned the principle of position,

which had to be re-introduced from India a thousand years later.

In short their understanding of Babylonian arithmetic must have

been very poor, since they managed to keep the worst features

of it, and to overlook the best. . . .

The Greeks used their intelligence

in a different way and did not see simple [i.e., practical --ACC]

things that were as clear as day to their distant Sumerian and

Babylonian predecessors.

It might be

thought that if the Sumerians were really practical people they

would have adopted a decimal system from the first, and quickly

abandoned the sexagesimal system. But there is much to be said

for the use of 12 instead of 10 as a base number. Ten has only

two factors: 2 and 5. But 12 has 2, 3, 4, and 6 -- or twice as

many: and in the higher multiples such as 60, the number of factors

is of course greater than the corresponding 20 of the decimal

system. Learning to think in terms of such a system would be

difficult for us now that we are so accustomed to the decimal

system., but there are some highly competent mathematicians who

hold that the change could be made and would be advantageous.

This is a matter of opinion of course, but since we have 10 fingers

the choice of 10 as a base seems more obvious -- and one suspects

therefore that these practical people saw a real advantage in

using 12 instead.

Yet it was purely a practical matter,

and not a theoretical one. The Greeks were more interested in

theory than practice. The contrast between the Sumerian and the

Greek attitude is seen in their treatment of problems

pg.5

of 19 pg.5

of 19

of Astronomy. In this connection,

O. Neugebauer says: 85

A careful analysis of the assumptions

which must be made in order to compute our texts shows nowhere

the need for specific mechanical concepts such as are familiar

to us fro the Greek theory of eccentrics or epicycles, or from

the corresponding planetary models of Tycho Brahe or Kepler.

. . . At no point can we detect the introduction of an hypothesis

of a general character.

Samuel Kramer makes

frequent reference to the fact that the Sumerians were an entirely

practical people, with no urge to search for truth for its own

sake, among whom there was not the slightest tendency either

to theorize or generalize, who sought for no underlying principles,

and undertook n experiments for verification. 86

Sarton gives some illustrations

to show how their mathematics arose out of a practical need,

i.e., business records and transactions. In the same way geometry

reached the Greeks after being developed to satisfy entirely

practical needs of the Egyptians. This is why Thales termed it

Geometry, for it was required originally to measure the land

in order to re-establish property boundaries obscured each year

by the flooding of the Nile. 87

Among the Sumerians and Babylonians,

banking houses sprang up and became the forerunners of world

economics as represented by our international institutions. Two

such Banks are known from cuneiform records by the names of Engibi

and Sons, established about 1000 B.C. and lasting some 500 years,

and Murasha Sons, founded about 1464 B.C. and dissolved finally

in 405 B.C. The latter established a system of mortgaging!88

Glass was

known to the Sumerians by 2700 B.C., and both they and the Egyptians

were experts in the working of it. 89

For drilling such hard substances they

used diamond drills, or some soft material coated with emery

or corundum. 90

85. Neugebauer, Otto, "Ancient Mathematics

and Astronomy" in A History of Technology, edited

by Charles Singer, et al., Oxford, UK, Oxford University

Press, 1954, \vol.1, p.799.

86. Kramer, Samuel N., From the Tablets of Sumer, Indian

Hills, CO., Falcon's Wing Press, 1956, pp.xviii, 6, 32, 58, 59.

87. Jourdain, Philip E. B., "The Nature of Mathematics"

in The World of Mathematics, edited by James R. Newman,

New York, Simon & Schuster, 1956, vol.1, p.10-13.

88. Reavely, S. D., "The Story of Accounting," Office

Management, April, 1938, p.8ff.

89. Wiseman, P. J., New Discoveries in Babylonia about Genesis,

London, UK, Marshall, Morgan & Scott, 2nd. edition revised,

(undated), p.30.

90. Boscawen, St. Chad, in discussing a paper by Sir William

Dawson, "On Useful and Ornamental Stones of Ancient Egypt,"

Transactions of the Victoria Institute, vol.26, 1892,

p.284.

pg.6

of 19 pg.6

of 19

A

tablet found a few years ago is inscribed by a certain Dr. Lugal-Edina,

dated about 2300 B.C., and in it we are told how surgeons of the day had

already learnt to set broken bones, make minor and major incisions and

even attempt operations on the eyes. Sicknesses are given names, and symptoms

carefully noted. Waldo H. Dubberstein of the Oriental Institute of the

University of Chicago, in reporting on this says: 91

One hundred years of exploration

and research in the field of ancient Near Eastern history have

yielded such astounding results that today it is unwise to speculate

on the further capacities and resources of these early people

along any line of human endeavour.

Medicine was

a carefully regulated profession with legally established fees

for various operations and very stiff penalties for failure or

carelessness -- evidently intended to protect the customer and

prevent charlatanism. This certainly suggests that the profession

was not simply a 'School of Magicians.'

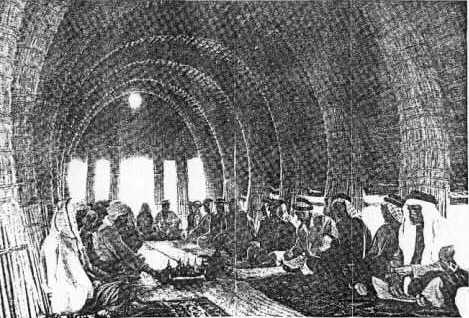

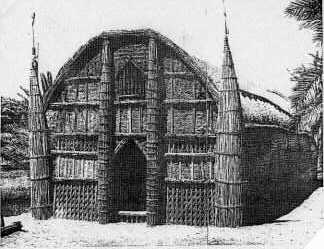

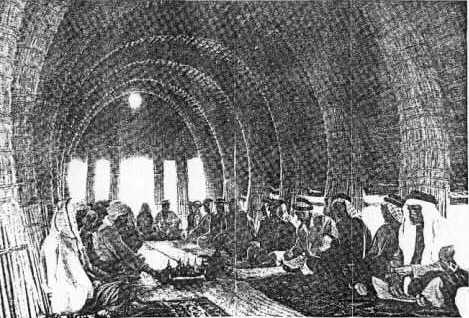

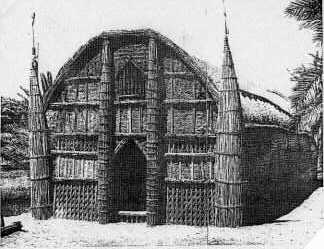

Although their buildings have largely

disappeared, they were noteworthy examples of the use of local

materials, i.e., mud-dried brick and reeds. The former are easily

visualized as promising materials; the latter are not. But as

a matter of fact, "reed huts" (mentioned in some of

the very earliest tablets are capable of a surprising beauty

and spaciousness as the accompanying illustrations indicate.

(Fig. 13 and Fig. 14). These are modem examples of course, but

there is every reason to believe that the designs have not greatly

changed through the centuries that intervene. Floor plans as

revealed by excavation indicate similar structures.

Fig. 13 A moderm Reed House in the Marsh Country

of the Lower Euphrates.

91. Dubberstein, Waldo H., "Babylonians

Merit Honour as Original Fathers of Science," Science

News Letter, September 4, 1937, p.148, 149.

pg.7

of 19 pg.7

of 19

By

the time the Sumerians arrived in Mesopotamia, they had domesticated

as many animals as were ever domesticated in that area, with

the exception of the horse which was tamed by the Hittites --

although they did have a draft animal, a mountain ass. And the

same may be said of grains. N.I.Vavilov always considered that

the Highland Zone to the north and east whence they had come,

was for this reason the most likely home of all such domesticated

plants and animal species as are commonly in use today. He called

it the "Source of Species." 92

Written records appear at the very

earliest levels, and even at Sialk there seems to have been no

period when they were without the use of metals. 93 |

Fig. 14

An exterior view of th 'Reed House' shown in the previous

photograph. |

Egyptian Civilization

The

same story is found to be true of Egypt. Here again there is

no true beginning. The Egyptians, like the Sumerians and the

founders of Tell Halaf, in Northern Syria, appear to have been

culturally creative from the very beginning, and to have developed

their technology exceedingly rapidly. Pastoral societies are

slower to develop, and the Semites who were largely pastoral

contributed little and borrowed much. Indo-Europeans meanwhile

did not even have a word of their own for City, the organization

of urban community life with all that this entails in terms of

civilization did not originate with them. It has been shown that

all their words for City, Town, etc., are loan-words.

94

The speed

with which Egyptian civilization developed was astonishing. P.J.

Wiseman, who has spent a lifetime in the area studying its past

history and closely in touch with the work of archaeologists,

says in this regard: 95

No more surprising fact

has been discovered by recent excavation than the suddenness

with which civilization appeared. . . . Instead of the

infinitely slow development anticipated, it has become obvious

that art, and we may say "science", suddenly burst

upon the world. For instance, H. G. Wells acknowledges that the

oldest stone building known is the Sakkara Pyramid. Yet as Dr.

Breasted points out, "from the Pyramid at Sakkara to the

construction of the Great Pyramid less than a century and a half

elapsed."

Writing of the latter, Sir Flinders

Petrie stated that, "the accuracy of construction is evidence

of high purpose and great capability and training. In the earliest

pyramid, the precision of the whole mass is such that the error

would be exceeded by that of a metal measure on a mild or a cold

day; the error of leveling is less than can be seen with the

naked eye.

The same famous Egyptologist

stated that the stone work at the Great Pyramid is equal to an

optician's work of the present day. 96 The joints of the masonry are so fine as to be scarcely

visible where they are not weathered, and it is difficult to

insert even a knife edge between them.

92. Vavilov, N. I., "Asia the Source

of Species," Asia, vol.37, no.2, February, 1937,

p.113.

93. Childe, V. G., What Happened in History, Harmondsworth,

UK, Penguin, 1942, p.64.

94. Eisler, Robert, "Loan Words in Semitic Languages

Meaning 'Town'," Antiquity, vol.13, no.52, December,

1939, p.449 ff.

95. Wiseman, P. J., New Discoveries in Babylonia About Genesis,

London, Marshall, Morgan & Scott, 2nd edition, revised, no

date, p. 28, 31, and 33.

96. Petrie, Sir Flinders, The Wisdom of the Egyptians, British

School of Archaeology. Publication No. 63, 1940, p.89.

pg.8

of 19 pg.8

of 19

Vere

Gordon Childe, speaking of their earliest earthenware remarks: 97

The pottery vessels, especially

those designed for funerary use exhibit a perfection of technique

never excelled in the Nile Valley. The finer ware is extremely

thin, and is decorated all over by burnishing before firing,

perhaps with a blunt toothed comb, to produce an exquisite rippled

effect that must be seen to be appreciated.

J. Eliot Howard

states that the hieroglyphics of the earliest periods indicate

that pottery, metallurgy, rope making, and other arts and techniques

were well developed,98

and W. J. Perry, quoting De Morgan, says. 99

What appears at a very

early date in Egypt is perfection of technique. The Egyptian

appears from the time of the earliest Pharaohs as a patient,

careful workman, his mind like his hand possessing an incomparable

precision . . . a mastery that has never been surpassed in any

country.

Fig. 15

One of the Parthian batteries, as reconstructed from parts found

near Baghdad. |

A

carved (or ground?) diorite head from Egypt was sold in London

some years ago for the sum of $50,000, and it was considered

by the experts at the time "never to have been surpassed

in the entire history of sculpture."100

It is hard to decide which of these

two civilizations produced the most remarkable metal wares. The

jewelled weapons of their noble dead are simply beautiful and

have to be seen to be appreciated. There are no essential metallurgical

techniques which they had not mastered very early in their history.

These include filigree, mold and hollow casting, intaglio, wire-drawing,

beading, granulation (in water?), welding, inlaying of one metal

with another, sheeting hammered so thin as to be almost translucent,

repousse, gilding on wood and other materials, possibly spinning

of metal, and later -- even electroplating using a form of galvanic

cell catalyzed with fruit juices and housed in a small earthenware

jar. 101 One of

these is illustrated in Fig. 15.

Egyptian medicine will be treated

in a later chapter since both it and mathematics are areas of

human endeavour in which these ancient people achieved much,

yet were clearly prevented from achieving more |

97. Childe, V. G., New Light on the Most

Ancient East, New York, Kegan Paul, 1935, p.67, (note 85).

98. Howard, J. Eliot, "Egypt and the Bible," Transactions

of the Victoria Institute, vol.10, 1876, p.345.

99. Perry, W. J., The Growth of Civilization, Harmondsworth,

UK, Penguin, 1937, p.54.

100. Magoffin, Ralph N., "Archaeology Today," The

Mentor, April, 1924, p.6.

101. Reported under the title, "Batteries B.C.", The

Laboratory, vol.25, no.4, 1956, published randomly by Fisher

Scientific Company, Pittsburgh, quoting Willard F. M. Gray of

the General Electric Company's High Voltage Laboratory, in Pittsburgh.

Gray reconstructed these batteries on the basis of archaeological

materials.

pg.9

of 19 pg.9

of 19

by reason of a certain attitude

of mind which seems to have been responsible for their failure to develop

the scientific method.

This failure had a fatal consequence.

The high technical competence in so many fields which they developed

rapidly and exploited to our continuing wonderment, halted at

a certain point, maintained itself for a few centuries unchanged,

began to decay rather suddenly, and finally passed out of memory

altogether until it was recovered from the dust of the centuries

by the labours of archaeologists during the past century or so.

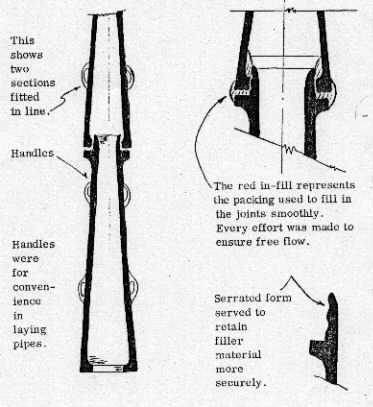

| Sir

Arthur Evan's researches in Crete have revealed the same pattern

of history. 102

The magnificent Palace of Minos with its system of hot and cold

running water, its rooms often decorated with a kind of wallpaper

effect done (as is done today) with a sponge,103 its extraordinary architecture, its beautiful pottery

-- in many cases patterned upon metal prototypes, its highly

organized court life, and its evidence of extensive trade and

commerce overseas -- all these achievements demonstrate clearly

that the craftsmen of the ancient Minoan Empire were in no way

behind the Egyptian and Sumerian in technical competence. Two

sections of their water piping illustrated in Fig. 16. Like the

drainage and sewage systems of the Indus Valley cities of Mohenjo

Daru and Changu Daru, they are equal in effectiveness to anything

we can install today. The underground sewage disposal system

illustrated in Fig. 17, from Northern Syria, is clear evidence

of a highly organized city life that presupposes the same kind

of technical achievement and awareness of the possibilities of

community responsibility. |

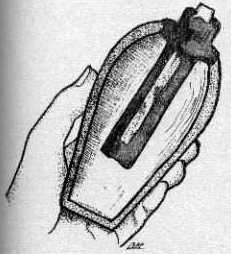

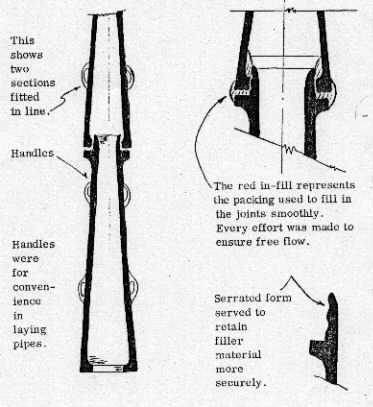

Some details of the plumbing found in the

Palace of Knossos in Crete. It is dated in Middle Minoan I by

Sir Arthur Evans. This would be somewhere about 2000 B.C., or

slightly earlier. The sections are all made of clay, and are

well baked.

The illustrations are taken from Evans' Palace of Minos,

Macmillan, Vol. I, p.143.

Fig 16.

The design of these pipes is based on sound engineering principles.

Turbulence is reduced to a minimum.

|

102. Evans, Sir Arthur, The Palace of Minos,

London, UK, Macmillan, in 5 vols. beginning publication

in 1921.

103. Painting with sponges: see Bulletin of the Royal Ontario

Museum of Archaeology, no.11, March, 1932, p.7.

pg.10

of 19 pg.10

of 19

Indeed according

to T. J. Meek, the people of Tell Halaf in Syria were never without metals,

and their finely fired pottery "no thicker than two playing card"

and beautifully designed, is equal to the best that the Sumerians produced.104 It is closely parallelled by some

of the earliest pottery found at Susa by de Morgan,105 a city which was closely tied in with

the Sumero-Egyptian Indus-Valley "Archaic Civilization" as W.

J. Perry aptly called it.

|

|

In contrast with the sewage

disposal system of modern Syrian towns this ancient 'main sewer'

from Ugarit (or Ras Shamra) looks pretty impressive. It was built

in the 2nd. millennium B.C., and is 9 feet underground, with

room to walk in.

|

In the streets above, lead

drains like this carried the water into the sewers, and kept

the streets clean and dry. In the photograph, the holes are in

the process of being cleaned out. It is difficult to realize

that this was made and installed 4000 years ago!

|

Fig. 17

104. Meek, T. J., 'The Present State of Mesopotamian

Studies,' in the Haverford Symposium of Archaeology and

the Bible, published by the American Schools of Oriental

Research, New Haven, CT, 1938, p.161.

105. de Morgan: quoted by Spearing, H. G., "Susa, the Eternal

City of the East" in Wonders of the Past, edited

by Sir J. Hammerton, London, Putnam's, 1924, vol.3, p.582.

pg.11

of 19 pg.11

of 19

Roots of Western Civilization

Here, in these

areas, lie the roots of all Western Civilization in its earlier

stages of development. From these centres, sometimes directly,

sometimes indirectly (as via the Etruscans), Europe derived the

inspiration of its culture.

The indebtedness

of the Greeks to the Minoans is now fully appreciated. 106 The Minoans had in turn

derived much of their culture from the Egyptians. Some influences

reached Greece directly from Asia Minor. Between these three

sources can be divided almost everything in Greek culture that

has a technical connotation: mathematics, architecture, metallurgy,

medicine, games, and even the inspiration of much of their art

-- all was borrowed from such non-Indo-European sources. Even

their script was borrowed. In fact one might say their very literacy,

for influential figures like Socrates, far from contributing

anything to the art of writing, actually strongly opposed it

as a threat to the powers of memory.

The same is true of Rome. The part

played by the Etruscans in the foundation of Roman Civilization

is immense. Sir Gavin de Beer in a recent broadcast in England

said:107

It may seem remote to us [to

ask who the Etruscans were] and yet it affects us closely for

the following reason. We regard the Romans as our civilizers,

and we look up to them as the inventors of all sorts of things

they taught us. But it is now clear that, in their turn, the

Romans learned many of these from the Etruscans.

106. Bibliography on Aegean Pre-history:

Blegen, Carl W., Zygouries: A Prehistoric Settlement in the

Valley of Cleonae, Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press,

1928.

Bosanquet, R. C., Excavations at Phylakopi in Melos ,

Macmillan, 1904.

Dinsmoor, W.B., The Architecture of Ancient Greece, London,

UK, Batsford, 1950.

Evans, Sir Arthur, The Palace of Minos, London, UK, Macmillan,

4 volumes, 1921-1935.

Heurtley, W. A., Prehistoric Macedonia, Cambridge, UK,

Cambridge University Press, 1939.

Holmberg, Erik J., The Swedish Excavations at Asea in Arcadia,

Lund, Sweden, Gleerup, 1944.

Mylonas, George, Prehistoric Macedonia: Studies in Honour

of F. W. Shipley, Washington University Series, Language

and Literature, No. 14, 1942, p.55 ff.

Pendlebury, John D. S., The Archaeology of Crete, London,UK,

Methuen, 1939.

Seager, Richard B., "Explorations in the Island of Mochlos,"

American School of Classical Studies at Athens, published in

Boston, 1912.

Valmin, M. Natan, The Swedish Messenia Expedition, Oxford,

UK, Oxford University Press, 1938.

Wace, Alan J. B., Prehistoric Thessaly, Cambridge, UK,

Cambridge University Press, 1912.

Weinberg, Saul, "Neolithic Figurines and Aegean Interrelations,"

American Journal of Archaeology, vol.55, April, 1951,

121 ff.

Xanthoudides, Stephanos, The Vaulted Tombs of Mesara,

London, UK, Hodder & Stoughton, 1924.

And, of course, numerous articles on the Linear Scripts, which

have now been deciphered and which originated in Crete, having

been adopted by the Greeks subsequently.

107. de Beer, Sir Gavin, "Who Were the Etruscans?"

in The Listener, BBC, London, UK, Dec., 8, 1955, p.989.

pg.12

of 19 pg.12

of 19

de Beer holds that whatever else might be said about these interesting

people, their language at least was non-Indo-European, and they were not

related either to the Romans or the Greeks. With this, agrees M. Pallottino,

an authority on the Etruscans.108 George Rawlinson, the great Orientalist

and classical scholar says in this respect:109

The Romans themselves notwithstanding

their intense national vanity acknowledged this debt to some

extent and admitted that they derived from the Etruscans their

augury, their religious ritual, their robes and other insignia

of office, their games and shows, their earliest architecture,

their calendar, their weights and measures, their land surveying

systems, and various other elements of their civilization. But

there is reason to believe that their acknowledgement fell short

of their actual obligations and that Etruria was really the source

of their whole early civilization.

To this list

D. Randall Maclver adds their martial organization -- and even

the name of the city itself in all probability. 110

African Civilization

Out of Africa

has come to us far more than just the Egyptian contribution,

even were this not a sufficient one. One does not think of Africa

as particularly inventive. As a matter of fact, however, so many

new things came from that great continent during Roman times

that they had a proverb, "Ex Africa semper aliquid,"

which freely translated means 'There is always something new

coming out of Africa.111

Among other things there came out of Africa "Animal Tales"

from Ethiopia. Edwin W. Smith and Andrew M. Dale point out in

this connection: 112

It might indeed be claimed that

Africa was the home of animal tales. Was not the greatest "literary

inventor" of all, an African, the famous Lokman, whom the

Greeks not knowing his real name called Aethiops (i.e., Aesop)?

Even in medicine

Africans have some remarkable achievements to their credit. To

mention but two: the Pygmies of the Ituri Forest had invented

an enema quite independently of its South American Indian

108. Pallottino, Massimo, The Etruscans,

Harmondsworth, UK, Penguin, 1955, p.46-73.

109. Rawlinson, George, The Origins of the Nations, New

York, Scribner, 1878, p.111.

110. MacIver, D. Randall, "The Etruscans," Antiquity,

vol.1, June, 1927, p.171.

111. Holmyard, E. J., "The Language of Science" (editorial),

Endeavour, vol.4, no.14, April, 1945, p.41.

112. Smith, Edwin W. and Andrew M. Dale, The Ila Speaking

Peoples of Northern Rhodesia, London, Macmillan, 1920, vol.2,

p.342.

pg.13

of 19 pg.13

of 19

counterpart, 113 and it is known that Caesarean operations

were successfully undertaken in childbirth emergencies before the White

Man had succeeded in doing it. 114

Out of Ethiopia came also coffee. 115 And quite recently African

art has been the 'inspiration' (for good or ill is a matter of

taste) of new forms of art. Very recently a kind of rocking stool,

inspired by an ingenious African prototype, has come into popularity.

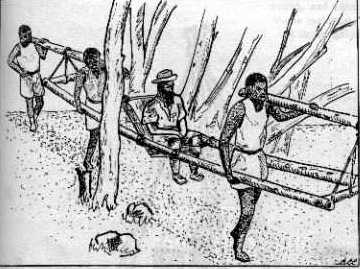

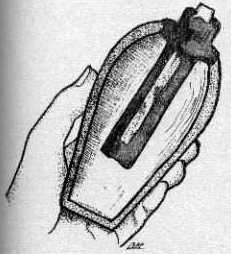

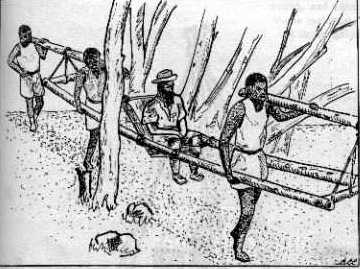

Their engineering skill is often

revealed in very simple things. A carrying chair, illustrated

in Fig.18, is so designed that the rider receives the absolute

minimum of jolts and rockings due to the unevenness of the ground.

It is a kind of super-whiffle-tree sling that equalizes the load

and guarantees smooth passage. It is simple and effective and

designed on entirely sound engineering principles of which the

makers were probably hardly aware.

Fig. 18

A four-man chair from French Equatoril Africa.

Sandaled Moslem Porters Carry Ill and Aged Hindus on the Tortuous

March

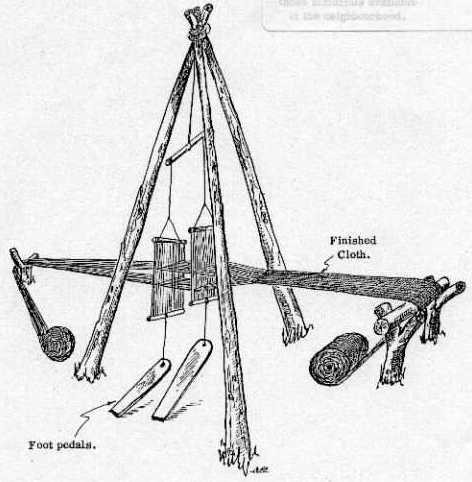

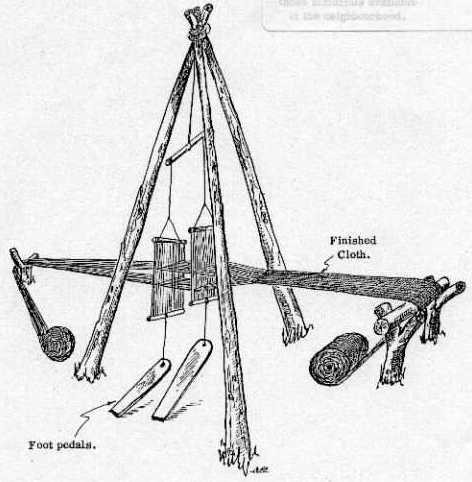

As a further witness to the same

kind of genius for simplified construction an African loom is

shown in Fig.19. It makes the most effective use possible of

locally available raw materials, and in fact uses their actual

form to the best advantage.

113. Coon, C. S., A Reader in General Anthropology,

New York, Henry Holt, 1948, p.340

114. Ackerneckt, Erwin, "Primitive Surgery", American

Anthropologist, New Series, vol.49, Jan.- Mar., 1947, p.32.

115. Anonymous, "The Story of Coffee" in The Plibrica

Firebox, vol.22, July - Aug., 1948, p.4, 5.

pg.14

of 19 pg.14

of 19

| Almost

every African community of any size has its own smelting furnace

and smithy. No part of this iron working art has been borrowed

from Europe. The whole process (and the refinements found in

some cases) is a native invention. The bellows used to increase

the oxygen supply and thereby the heat at the hearth, are of

native design and manufacture and are very varied in form. The

pipes which convey the air into the furnace are also home made.

Suitable clay is plastered around pieces of wood of the proper

size and shape (whether curved, straight, or even forked), and

then the whole is burned in a fairly hot fire. This reduces the

wooden insert to ashes and leaves the desired pipe form, shaped

and baked all ready for use. When the ore has been reduced and

the metal is removed from the dismantled furnace it is worked

by hand. The metal may be hammered into sheet, drawn into wire,

or forged into other forms such as vessels, blades, etc., as

desired. It is not surprising that we, having largely learned

from Africa the basic techniques of iron-working, should refer

to our iron metalworkers as Blacksmiths. R. J. Forbes says that

although today African smiths often obtain their raw materials

from European sources, the Negro smiths "are very ingenious

craftsmen in inventing and using new tools and types of bellows".

116 |

A native loom whose design is common to many parts of

the world,

and which uses only those materials available in the neighbourhood.

From A History of Mechanical Inventions,

Abbott P. Usher, Harvard University Press, 1954.

Fig. 19

|

116. Forbes, R. J., Metallurgy in Antiquity,

Leiden (NL), Brill, 1950, p.64.

pg.15

of 19 pg.15

of 19

Invention "Firsts"

Samuel

N. Kramer has recently published a volume resulting from a lifetime

of cuneiform studies which he

titles From the Tablets of Sumer, and his subtitle takes

the following form: Twenty -five Firsts of Man's Recorded

History. 117

It is an impressive collection of "firsts", yet one

will feel at times that he has introduced a few cases which are

only rightly termed so, by a kind of special pleading. But on

the whole his collection shows that their inventiveness was by

no means limited to mechanical things, but applies equally well

to certain forms of literature -- and indeed to the very idea

of collecting libraries, writing histories, and cataloguing books

for reference.

Among the literary achievements

of the Egyptians are to be listed what was surely the first 'moving-picture'

sequence, 118 and

the first Walt Disney Cartoon. 119. Gloves and camp stools are found first in Crete,

120 soap in Egypt,

121 virtually all

carpenter's tools (saws, squares, bucksaws, brace and bit, etc.)

from the Etruscans 122

-- with a novel brace and bit, 123 and the 'level' from Egypt. 124 The Etruscans invented lathes. 125 The Egyptians

built a pipe-organ using water to obtain a uniform air pressure

apparently. 126

Folding umbrellas and sun-shades were first designed in China

127 and were not

introduced into England until centuries later where the introducer

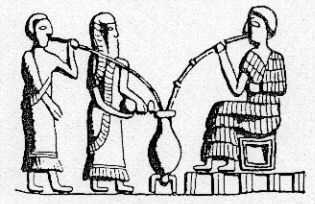

apparently almost lost his life! The Sumerians used straws for

drinking with, 128 (shown in Fig 20), and bequeathed to their

successors chariot wheels which were made of plywood using exactly

the same technique for the manufacture of it as we use today.

129 Africans were

using vaccines long before the White

Fig. 20 Sumerians, drinking from Straws.

117. Kramer, Samuel N., From the Tablets

of Sumer, Indian Hills, CO, Falcon's Wing Press, 1956.

118. "A Cinematograph Touch in Ancient Egyptian Art: Wall-paintings

that Suggest Moving Pictures", reproduced from P. E. Newberry's

"Beni Hasan" in the Illustrated London News,

Jan.12, 1929, p.50,51.

119. Hambly, Wilfrid D., "A Walt Disney in Ancient Egypt"

in a Letter to the Editor of 'animated animal figures' behaving

like people! [Scientific Monthly, October, 1954, p.267-8

with illustrations].

120. Gloves and camp stools: see Axel Persson, The Religion

of Greece in Prehistoric Times, Berkeley, CA, University

of California, 1942, p.77.

121. Soap: see on this Rendel Harris, "Soap" in the

Sunset Papers, published privately in England, 1931.

122: Tools: see George M. A. Hanfmann, "Daidalos in Etruria",

American Journal of Archaeology, vol.39, April - June,

1935, p.192f.

123. Brace and bit: an illustration of this is given in The

Illustrated London News [April 12, 1930, p.623] in a series

of articles by G. H. Davis and S. R. K. Glanville entitled "Life

in Ancient Egypt: Astonishing Skill in Arts and Crafts."

124. Levels: see George Sarton, A History of Science,

Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press, 1952, p.124, footnote

94.

125. Lathes: see A History of Technology, edited by Charles

Singer, et al., Oxford University Press, 1954, vol.1,

p.192, 518.

126. Apel, Willi, "Early History of the Organ," Speculum,

vol.23, 1948, p.191-216.

127. Umbrellas and Sunshades: a number of bronze castings used

in the construction of these large umbrellas are to be

seen in the Royal Ontario Museum Toronto, Canada.

128. Drinking straws: well known from the monuments and from

seals. The line drawing in Fig. 20 is probably from a

seal.

129. Linton, Ralph, The Tree of Culture, New York, Knopf,

1956, p.114.

pg.16

of 19 pg.16

of 19

Man adopted the measure: 130

and there is a record of the invention of a malleable

glass, the secret of which was destroyed by the ruling monarch, along

with its originator, for fear of upsetting the economy. 131

Every form of building technique now commonly used (including

concrete) is found among non-Indo-Europeans, and in many cases

long antedating the Romans, especially the arch, barrel vault,

dome and cantilever principle of construction. The barrel vault

was achieved in Babylon without the need of a supporting scaffold

under it, by starting against an upright wall, which was later

removed. The cantilever principle was used by the Egyptians (among

others) in strengthening their larger seagoing vessels to prevent

them from 'breaking their backs,' as marine engineers term it.

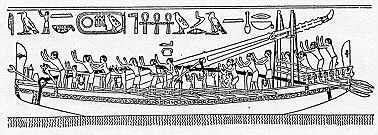

One such vessel is shown in Fig.21. Speaking of boats, James

Hornell, an authority on water craft as developed by primitive

and ancient people, opens a paper on the subject with these words:

132

There can be no doubt

that to Asiatic ingenuity we owe the beginnings of the world's

principle types of Water Transport. Early man in Asia invented

means of extraordinary diversity to enable him to cross rivers,

etc.

Fig. 21

An Egyptian sea-going vessel from the tomb of Sahure, c. 2700

B.C., showing the rope tensioner

stretched from one end to the other, supported on a brace at

the centre, and tightened with a torsion bar member

on sound engineering principles.

The vessels

illustrated or referred to include every type of small craft

from mere floats to coracles and large outrigger sailing vessels,

etc. If we bear in mind that China gave us the stern-post rudder,

and watertight compartment construction, as well as canal locks

for inland waterways,133

and that the Koreans built the first true battleship, with iron

cladding -- notwithstanding the claims made for 'Old Ironsides'

in Boston Harbor, it will be seen that we have not contributed

a great deal basically to marine engineering. Isabella L. Bishop

says of this Korean warship, that it was named Tortoise Boat,

and was "invented by Yi Soon Sin in the 16th century, enabling

the Koreans to conquer the great Japanese General Hideyoshi in

Chinhai Bay.134

Naphtha gas was first used

by the Sumerians,135

eye salves in multiple tubes probably by the same

130. Vaccines: see Melville Herskovits, Man

and His Works, New York, Knopf, 1950, p. 246.

131. Malleable glass: the details of this are given by Stanko

Miholic, "Art Chemistry," Scientific Monthly,

vol.63, December, 1946, p.460.

132. Hornell, James, "Primitive Types of Water Transport

in Asia: Distribution and Origins," Journal of

Royal Asiatic Society, London,1946, Parts 3 and 4, p.124-141.

133. Needham, J. Science and Civilization in China, Cambridge

University Press, 1954, vol.1, p.240-243.

134. Article by Isabella L. Bishop, "Koreans," in the

Encyclopedia Britannica, 14th edition, 1937, vol.13, p.489,

with illustration.

135. Naphtha Gas: as we have already mentioned, the Chinese piped

this gas as early as 450 B.C. But it was also used by the Babylonians

for divination purposes according to R J. Forbes, ("Chemical,

Culinary, and Cosmetic Arts," A History of Technology,

edited by Charles Singer, et al, Oxford, UK, Oxford University

Press, vol.1, 1954, p.251). It is said to have been used by the

Sumerians probably, in furnaces for heating metals (R. J. Forbes,

Metallurgy in Antiquity, Leiden, Netherlands, Brill, 1950,

p.111.

pg.17

of 19 pg.17

of 19

people,136 and spray-painting by palaeolithic man!137 Cigarettes were known to the North

American Indians long before Europeans had even heard of tobacco:138

spectacles are probably a Chinese invention:139 and safety pins came from the Etruscans.140 The Chinese did many things with glass,

for according to Bruno Schweig there is evidence of glass mirrors as early

as 2000 B.C.:141 and although the source of my information here is not the best,

there is a reference to the first 'windows' of glass in a collection of

Chinese Stories. It is said that in the reign of Emperor Ming, a man named

Wing Dow invented a 'device' which he called Looking-through-the-Walls,

whence it is claimed we now derive our word Window, being a corruption

of the inventor's name.142

Although the abacus seems a very

slow and primitive way of making calculations, recent experiments

undertaken by experts in both the ancient instrument and the

modern electrically operated comptometer, have shown that in

the hands of a skilled operator it can hold its own against all

mechanical devices (excluding computers), except in one particular

type of calculation.143

136. Eye salves: Forbes, R. J., in A History

of Technology, edited by Charles Singer, et al., Oxford

University Press, 1954, vol.1, p.293

137. Spray painting: Leakey, L.S.B., in 'A History of Technology,

edited by Charles Singer, et al., Oxford University Press,

1954, vol.1, p.149. This is possibly begging the point a little!

It is assumed from the nature of certain paintings that they

were done by blowing (or splattering)

the paint from the mouth (!) using baffles to limit it as required.

Certainly it does seem to have been sprayed, somehow.

138. Cigarettes: see note, under the title "The Sacred Cigarette."

It is reported that thousands have been found in cave-shrines

as native offerings in Arizona (in section "Far and Near,"

Discovery, vol.19, no.6, June, 1958, p.262). We have already

mentioned cigar-holders: and of course, the Indians were the

originators of the pipe for smoking tobacco.

139. Spectacles: see Ethel J. Alpenfels, anthropologist with

the Bureau for Intercultural Education, in an article entitled

"Our Racial Superiority," abstracted in The Reader's

Digest, September, 1946, p.81, from Catholic World,

July, 1946, p.328 ff.

140. Safety pins: illustrated in Antiquity, June, 1927,

p.170 in an article by D. Randall MacIver, "The Etruscans."

141. Mirrors: Schweig, Bruno, "Mirrors," Antiquity,

vol.15, no.59, September, 1941, p.259.

142. Windows: see Phyllis R. Feuner, Giants, Witches, and

a Dragon or Two, New York, Knopf, 1943, p.185.

143. Abacus: these experiments were reported as a note, in the

Magazine His, (Chicago, IL, IVF publication. Oct., 1957),

under the title "Misplaced Conceit." (no page numbering

in this section).

pg.18

of 19 pg.18

of 19

Conclusion

Comte

du Nouy, after a backward look at the 'rostrum of ingenuity'

which meets the eye from antiquity, expresses the conviction

that 144

Intelligence

does not seem to have increased radically in depth during the

last 10,000 years. As much intelligence was needed

to invent the bow and arrow, when starting from nothing, as to

invent the machine gun, with the help of all anterior inventions.

The point

is well taken, and one demonstration of the wisdom of this observation

is that the experts find it quite impossible to determine now,

how the first bow ever came to be invented. Their reconstructions

are as varied as can be: which tends to show that such a weapon

would certainty not, as it were, occur easily to its originator

if we cannot even imagine how it originated with one right in

front of us.

144. du Nouy, Comte, Human Destiny, New

York, Longmans Green, 1947, p.139.

pg.19

of 19 pg.19

of 19  Copyright © 1988 Evelyn White. All rights

reserved

Previous Chapter Next

Chapter

Copyright © 1988 Evelyn White. All rights

reserved

Previous Chapter Next

Chapter

|