|

|

Preface Introduction ChaptersChapter 1 Chapter 2 Chapter 3 Chapter 4 Chapter 5 Chapter 6 AppendicesAppendix I Appendix II Appendix III Appendix IV Appendix V Appendix VI Appendix VII Appendix VIII Appendix IX Appendix X Appendix XI Appendix XII Appendix XIII Appendix XIV Appendix XV Appendix XVI Appendix XVII Appendix XVIII Appendix XIX Appendix XX Appendix XXI IndexesReferences Names Biblical References General Bibliography |

THE LINGUISTIC EVIDENCE. "But the earth had become a

desolation...." The rendering above departs from that to be observed in almost all the better known

English translations in three ways:* the use of a disjunctive (but for

and), the use of the pluperfect in the place of the simple perfect, and the use

of became in place of the simple was. Of the disjunctive, little

need be said. The Hebrew stands for both the

conjunctive and the disjunctive particles, and the context alone can determine

which is the more appropriate. There is, as we have seen, some reason to prefer the disjunctive in view of the indicated pause in

the Hebrew text at the end of verse 1. In Appendix XIV will be found a

number of illustrations of this use, in- cluding some instances in

which the correctness of the disjunctive form is borne out not

merely by the obvious sense of the passage quoted but by its

reappearance as a quotation in the New Testament where the Greek has

"but", not "and" (ie., The use of the pluperfect is dealt with in the following chapter, the point being reserved for discussion only after the translation of the verb itself has been

carefully considered. The most critical issue is whether * See Appendix III. the true significance of

the verb, and indeed of the second verse as a whole, hinges upon the settlement of this point. Granted that this point can be settled, the

other two points will probably not be ser- iously disputed. Now this discussion does

not make easy reading, not only because of the subtleties involved

(as will appear) but also because the verb we must examine in its

commoner forms happens also to be the very verb we must use in its

commoner forms in order to make the examination! One runs into this kind of

thing: "In such a case, the word was is incorrect....". Or

one might put this: "In such a case, the word "was" is incorrect...

."; or " the word WAS is incorrect"; or "the word was is

incorrect....". At any rate, this points up the nature of the problem! Thus we are forced to employ various

devices (underlinings, capitals,

italics, and 'quote' marks) in order to make each point clearer.* And this kind of constant typographical

switch- ing is most distressing to

even a thoroughly dedicated reader. But it seems unavoidable. In view of the fact that

one can scarcely construct an English sentence of any complexity

without using some form of the verb "to be", it is difficult

to realize that there are well-developed languages which make little or no

use of it at all in the simple copulative sense. When, in English, we

express the straightforward idea, "The man is good", the verb

"to be "is used merely to connect together the words man and good. Many languages, and indeed many children,

simply say, "man good",

considering the connective verb quite unnecessary. A child will say, "Me

good boy": an Indian might say, "Me brave man". Hebrew does the same. Benjamin Lee Whorf, the

'founder' of that branch of the study of language known as

Metalinguistics, observed that a Hopi Indian, for example, has difficulty in

understanding why we say, "It is raining". because to his way of

thinking the It is the rain.

One might just as well say, "Rain is

raining" - which of course is a redundancy. So he wonders why we don't

simply say, as he does, "Raining"! Neither * In the biblical quotations

which follow, we have tried to indicate to the reader

where the verb "to be" has been supplied in the English

though absent in the original by put- ting the verb in

brackets. Thus: Gen. 3.11,

"Who told thee that thou (wast)

naked?" indicates that (wast) has been supplied to complete the

English sentence. the It

nor the Is serves any useful purpose in this English sentence and common sense,

therefore, would argue the leaving out of both of them. But this would not sound correct to

us. Yet, as we have observed, Hebrew shares

the un-English view that a verb is not needed here since it

really contributes nothing. Now, in translating, it is

quite customary to equate the Hebrew verbal form by Hebraists for many years that the

equation is not strictly valid. In English, being

is a kind of static concept, things simply "are" this or that. When we say,

"The man is tall", we are not speaking of a dynamic event but a

more or less static situation.

"The field is flat" is indeed a

static situation. In both these

sentences English requires some part of the

verb "to be" in order to satisfy our sense of linguistic

propriety. Yet in spite of the

possession of the verb necessary here and the

verb is would therefore not be represented in the Hebrew. The reader who is limited

to English will find that in some editions of the Bible, especially

in the Authorized Version, a means is prov- ided, simply by the use of

italics, to show where any part of the verb "to be" has been

inserted in the English translation to complete the sense though not found in

the original Hebrew. For example, if one opens a first edition of

the Scofield Bible at (say) page 21, some eleven copulative or

connective occurrences of the verb "to be" will be found in italics,

appearing in the text as is, art, be, and was:

and on page 395 some 39

examples will be found in the forms was and were In every instance the word

has been supplied by the translators where the Hebrew original did

not consider any verb necessary.* * Any page would, of course, have

served to illustrate the point, and any

printing of the Authorized Version will show it. Thus, for example from Jud. 6.10 to 7.14

we have in 6.10 am, 13 be, 15

am and is, 22 was 24 is, 25 is, 30 be; and in 7.1 is, 2 are and are,

3 is, 12 were, 13 was, and 14 is. All these are copulative and the original. On the other hand, in Judges 6.27 the verb was is not in italics since it is found in the Hebrew, and it is clear that the

intent of the writer was something beyond the mere copulative

force of the verb: as for example Continued

page 44. Thus the fundamental idea

behind the Hebrew verb cisely what would be copulative in English

but is a far more dynamic concept. This is indicated to some extent

by its possible etymology. A number of authorities,

including Gesenius and Tregelles, believed that the primary meaning

was that of "falling" - comparing the word with the Arabic From this came the idea of

"befalling" in the sense of "happening", and so "to fall

out", and thence "to come to be", ie., "to become". From this idea of having

become, we pass easily into the meaning "to be" in the sense

of having existence but the copulative sense usually attributed to it

seems without logical foundation. Subsequently, Tregelles

came to believe that the concept of "fall- ing" was not really primary,

and that the notion of "being" came instead from that of

"living". From the concept of "living" the idea of "being" is

readily derived so that it comes easily to mean "to be": but this kind of being is

dynamic being, living being, not the static kind of being which is

equative as when one says, "This is (ie., equals) that", but the kind

which is implied in such a sentence as "He is alone", or "He

is with thee". Thus while Benjamin Davies

gives the basic meaning as "to be" - usually with the sense of

"to exist", "to be alive", "to come into being", and so

"to become" - Brown, Driver and Briggs list the meanings of "to become"; and

"to be". And under the

last heading they add subsequently in parenthesis, "often

with the subordinate idea of becoming". The concept of dynamic as

opposed to static being is of great importance to an

understanding of the Hebrew usage of the word. Boman, in a critical study

of the verb, concludes that it is never used copulatively at all

and that all the usual illustrations of such a use provided in lexicons

are not really valid. He does not consider that even Ratschow, who

made a quite exhaustive study of Old Testa- ment usage, was really

able to give any clear unequivocal instances. Thus, for example, in Gen. 2.25 the

sentence, "and they were "And it came to be that...." In Gen. 23.17 the verb 'to be'is set in italics 5

times! We need this insertion of

the verb to fill out the

sentence, but the Hebrew writer did not see any need for it and so

omitted it entirely. ( at the moment of speaking

the writer is observing the simple fact of their nakedness but that

this was how they lived, daily. They "went about" without

clothing and without shame.

Subsequently, they suddenly became aware that

they were naked and this awareness brought with it a sense of

shame not experienced before. This

was nakedness in a new way and

it occurred quite suddenly - suddenly enough that Adam

"discovered" it with a sense of shock. That this was in the nature of a

discovery is implied in the Lord's words (in Gen, 3.11), "Who told

thee that thou (wast) naked?". The question would have been pointless

otherwise. Thus the real emphasis here is no longer upon the

circumstance that Adam and Eve had been living naked in the Garden of

Eden but that they had both suddenly discovered a fact which caused them

to be ashamed. Boman argues that the

simple "is" or "was" in an English sentence is never expressed in

Hebrew and that where it IS expressed it does not mean what the English

translation implies. It is used in the sense of eventuality: it is not

used for a simple fact or circumstance or situation. One might wonder how Hebrew would then

distinguish between the phrase, "the man is

good", and "the good man".

In a sense they convey the same basic

idea, but there is a subtle difference. In any case Hebrew can make the

distinction. The first would appear simply as "the man

good" (ha-ish tobh: as "the man the good

one"(ha-ish ha-tobh: One might then ask further, How would the

distinction be made between the sentences,

"the man is good" and "the man was good"? In Hebrew, the context is

allowed to decide the matter. While

it might seem that this would

be difficult (as upon occasion it is), the number of such occasions

must be remarkably small for there seems to be not the slightest

hesitation in omitting the verb, whether the sense of "is" or

"was" is intended. Such will be apparent from the footnote with examples on

page 43 of this Chapter and from the more elaborate study which will

be found in Appendix IV. Some have felt this to be

a real difficulty. Barr, for

example, argues that the verb must

be inserted when the tense is past and the situation no longer exists.

For example, if a writer meant to say, "The man was good....

but is no longer so", ie., "The man was once good", then he

would insert the appropriate form of the verb "to be" to indicate the

altered circumstance. But this rule does not hold. For example, according to this principle, the record of

Job's complaint in Chapter 29 should have the verb was

in the original since the situation has clearly been altered by his diseased condition.

Yet, in point of fact, the Hebrew omits it. It is not merely

that the situation is no longer true today: the situation was no

longer true when the statement was made. Thus Job, inverses 14 and 15

and 20, tells his self-appointed comforters that he was formerly -

ie., was once - a father to the blind and feet to the lame: he once

enjoyed fame and recognition and his roots once spread beside the waters

like a flourishing tree. The meaning

of his complaint is

unmistakable. He WAS all those things but is no longer so: yet the Hebrew

writer saw no need to express the connect- ive verb "was"

in such a situation. We have another example in

the case of Pharaoh's servants in Gen. 41. Here the butler recalls (verse 12) how he

and a fellow tradesman were in prison

and how at that time a Hebrew named Joseph was also with them.

Clearly the situation had now changed for the speaker, since he

is a free man - and his fellow tradesman is dead. He refers back, therefore,

to a situation which from his point of view no longer

exists and the English translation in verse 12 properly inserts the verb

"was" - but the Hebrew omits it.

Some might argue that the

situation for Joseph had not changed, since he was still in prison! But

one must surely consider the circumstances from the point of view of

the speaker. The omission of the verb in reporting his speech

shows, therefore, that it is not required merely because there is the

implication of altered circumstance. He was, as he says, once in the

same prison: but he is no longer so, yet the Hebrew writer evidently

saw no need for the verb There are numerous

illustrations of this kind of situation in the Old Testament, but many of

these require a somewhat elaborate excursus in order to show

how we know there has been a change. Some are straightforward enough: as, for

example, where Gen. 12.6 records that "the

Canaanite (was) then (ie. , at that time) in the land". But there are probably far more examples

which are in reverse. There are innumerable examples where the

situation is quite UN-changed and yet

the verb "to be" is inserted in the original in the appropriate

form. This is a most common occurrence. Thus, for example,

throughout the first chapter of Genesis there is the recurrent phrase,

"And it was so". Here the

Hebrew inserts the verb. According to Barr, this insertion should

imply that the situation or circumstance is

no longer true. But this is surely not the case. Genesis 1,

verses 3, 5, 7, 8, 9. and so forth, would all be properly translated if

one were to render the phrase which in English reads, "And

it was so", as "it became so", but it would surely be quite

improper to suppose that the author means, "And it was once but is no longer

so....". Thus, the insertion of the verbal form

"was" in a Hebrew sentence is not intended to signify

that the circumstance is no longer true, for these evenings and these

mornings retain their pre-eminence of position in the processes

of time. Thus when Barr proposes

that the verb is inserted in

Gen. 1.2 in order to show that the desolation was a temporary one and no

longer exists, he is implying the existence of a rule which certainly

cannot be unequivocally demonstrated from biblical usage. And to say

at the same time, as Barr does, that on this account "it would

be quite perverse to insist on the meaning 'became' here", is

clearly going beyond the evidence. Indeed, he would perhaps be forced to

admit that to follow out his own proposed rule and render Gen. 1.5,

"and the evening and the morning were once a second day but are

no longer so", would indeed be absurdly perverse! But, by contrast

to this absurd rendering, it would make very good sense to

render the Hebrew, "and the evening and the morning became the second

day", for this is precisely the truth of the matter, and the Hebrew

has seen fit to insert the verb in order (as I believe) to make

this quite clear. In this eventful

period, it did become the second day

of the week. From all of this it would appear

that the decisive factor which determines whether the verb will be

inserted or omitted is not related to tense. Nor is it related to circumstance, if by

this is meant merely that what is

reported is no longer the case. Boman seems to come much closer to the

truth when he underscores the fact that only where the sense is

dynamic does a Hebrew writer introduce the verb rounding its employment

which bear out the contention that it is basically a verb of action

rather than condition. First of all it can be, and frequently is,

used in conjunction with the infinitive or a

participle of another verb of action. For example, Nehemiah (2.13) tells how he

was in the habit of inspecting the walls of his beloved city

Jerusalem while they were still under repair. Thus he says, "And I

was ( walls of

Jerusalem". This could easily

have been expressed by the appropriate form of

the verb engagement.... A list of examples

will be found in Appendix VIII and a study of such usages

indicates that the idea is best expressed by rendering the verb or phrase as "kept

---" (Ezek.44.2), "succeeded in ---" (II Chron. 18.34), "remained

---" (I Ki. 22.35), "continually---" (Gen. 1.6), "habitually ---"

(I Sam.2.11, Gen.39.22), "was ever ---" (I Ki. 5. 1), "always ---"

(II Ki.4.1, Ezek.44.2), "was daily ---" (Neh. 5.18), etc. All these

imply something beyond a static situation, even in Ezek. 44.2, for the

idea is positive closure of the gate, that is, keeping the gate closed

and not merely "leaving it shut".

It is a case of maintenance rather

than abandonment. In II Chron. 18.34 the mortally wounded king

obviously did everything in his power to hold himself upright in

his chariot so that his supporters would not lose heart.. In Gen. 1.6

the atmosphere actively divides, ie. , main- tains, the division between

the waters above it and those below: there is nothing static about

this process at all. And so it will

be found in every instance of usage

in connection with either a participle or an infinitive. It is analogous to the English usage in such

a sentence as "the water is

boiling" or "the man is still angry". Secondly, it appears in

the niphal or passive form, as though the sense was "to be

be-ed", just as in English an active form (e.g. "fold") is

converted to a passive form* ("fold-ed") by the addition of "-ed". It is

much more difficult to think of the English verb "to be" in a passive form because

to us it tends to be essentially a static concept. In Hebrew, since

it is an active verb, the formation of a passive did not seem strange

and the verbal form of the active is routinely changed to a

passive form without hesitation.

Thus in I Ki.l. 2 7 a literal

translation would be, "Is it from my lord the King that this thing has been

be-ed" (!), which would obviously have to appear in English as

"has been done" or "has come about" (in Hebrew : of action. Similarly, that

often quoted passage from I Ki. 12.24 (lit- erally, "For from me

this has been done" ( is in the Authorized

Version, "For this thing is from me". Most lexicographers simply say

that in the niphal or passive form the verb is best rendered

"come to be", ie., "become" or "happen". This is the sense of Deut. 27.

9 for examples "This day ye have become a people for the Lord your

God". Boman's third point is

that the verb with other verbs, in sentences which have a

clearly active context. For example, in Gen. 2.5

it is written, "Every plant before it was in the earth and every

herb of the field before it grew....". And, * See Appendix VII for illustrations. significantly, this is

followed by the words, "And there (was) not a man to till the ground". In the first

instance the verb is used as a parallel to the verb

"grew"; and in the final phrase the verb is omitted because it is a statement

of a static situation rather than an activity. Another illustration of

this kind of parallelism is to be observed in Gen. 7.17,"And the

Flood was forty days on the earth", followed by verse 19 which says,

"and the waters prevailed exceedingly upon the earth". Clearly the picture is one of the

turbulence of an over- whelming flood and not

merely of a deep but placid sea of water. Boman suggests quite

properly I believe, that throughout the Creation record, the verb being" rather than

merely factual existence. God created, or spoke, or made, and "it came

to be so", ie., "sprang into being", certainly indicating an active

process of realization rather than a static cir- cumstance. Indeed, it is found in parallel with the

Hebrew which has the meaning of

"realization" in such passages as Isa. 7. 7 ("It shall not stand,

neither shall it come to pass") and Isa. 14.24 ("Surely as I have

thought, so shall it come to pass"). Now the verb It is a very versatile word obviously: and

only by associating it with various prepositions

( forms (infinitives and participles)

can its full range of meanings be set forth

adequately.* As Boman observed: " word which can me an

everything possible and therefore des- ignates nothing characteristic. Closer examination, how- ever, reveals that this is

not the case." Ratschow examined the

occurrences of with a thoroughness hardly to be excelled

and concluded that the verb had three essential meanings

which are given in the following order: "to become",

"to be" in the sense of existing or living, and "to

effect". Boman, in discussing

Ratschow's findings, states his opinion that these meanings really form

a single basic unity with an internal relatedness. In his discussion he first of all points

out something which was elaborated by Benjamin Lee

Whorf, namely, that the meanings people * See Appendix VIII for

illustrations. attach to the words they use reflect their own

views of reality, and that these views are not at all the same as those

generally shared by people of another language group. Many

non-Indo-European peoples tend to equate things which we would consider quite

separate and distinct.

For example, to say in English that something IS wood is not to identify the thing itself with the wood

that it is made of, but rather to say that it is made "out of "

wood. By contrast in many other languages, including Hebrew, the thing and

the wood are ident- ified, equated, considered as inseparable. Such a

sentence as "the altar and its walls (were) wood"

(Ezek.41.22) means to the Hebrew mind that altar, walls, and wood are a single

entity, an equation, one and the same in the particular instance. A verb is

not necessary. Similarly, "All the Lord's ways (are)

grace and truth" would mean to us that there is grace and truth IN all the

Lord's ways. But not so to the Hebrew mind. This is not an aspect

of the Lord's ways, it is a factual commonality. As Boman expresses it,

"The predicate inheres in the subject". Thus he further observes: "The most important meanings and uses of our

verb "to be" (and its equivalents in other Indo-European

languages) are (i) to express being or existence, and (ii) to

serve as a copula." But having said this, Boman comments: "Hebrew and other Semitic languages do not need

(my emphasis) a copula because of the noun clause

(such a clause as 'the altar is wood'). As a general rule,

therefore, it may be said that istic mark of it is a true verb with full verbal force." In short, he concludes that whether accompanying preposition or is qualified by one,

"it signifies real becoming (his emphasis), what is an occurrence or a

passage from one condition to another.... , a becoming in inner

reality...., a becoming something new by vocation....". Such

is Boman's view, a view supported by many illustrations, some of

which will be found later in this text. It is a view arrived at by a most careful study of the whole question in which cognizance has been

taken of the previous labours of a large number of recognized

European scholars. It is a view which

completely contradicts the rather bombastic state- ments of some recent

writer s whom we have already quoted as saying in effect that every

Hebrew scholar knows precisely the opposite to be the case! It is a view

which strongly supports the argument that chaos was not the initial

condition of the created earth. Other linguists agree with Boman.

Non-Indo-European languages do not employ the

verb "to be" as English does. In an interesting paper entitled, Language

and Philosophy, Basson and O’Connor ex- amine the relationship

between structure of language and form of philosophy. This examination

includes as an important part of their thesis a study of the verb

"to be" used in the following ways: (1) As a logical copula, involving: (a) Predication: "the

leaf is green". (b) Class inclusion:

"all men are mortal". (c) Class membership:

"the tree is an oak". (d) Identity: "George

VI was king of England". (e) Formal implication:

"wisdom is valuable". (2) In an existential sense:

"God is". (3) In any other sense

peculiar to the language in question. "Some interesting and possibly important information was supplied to us (from a

questionnaire sent to a number of phil- ologists and linguists) on

this topic. Most interesting was the large number of

languages which made a sharp distinction between the existential

'is' and the copula.* Semitic lang- uages have in general no

copula, but Hebrew and Assyrian both have a special word

for 'exists'. Malay (an Austro- nesian language) is

similar to Hebrew in this respect. Tib- etan uses 'yin' for the

copula and 'yod' for existence, but a sentence like 'That hill

is high' might use either word accord- ing to the sense of the

context." All the lexicons deal with

the verb have in my possession, nor

is there available to me at the present, a copy of the original work

completed by that most famous of Hebrew lexicographers, Friedrich Heinrich

Wilhelm Gesenius, in 1812. I do have, however,

translations of his original work edited and amended in various ways by some of

the scholars who followed him. * See further Appendix

IX Christopher Leo's edition of Gesenius,

published in 1825, gives a list of the meanings of

the verb with illustrative examples from the Old Testament which may be

summed up under the following basic headings: "to

be" illustrated by reference to Exod. 20.3 ( a curious circumstance since it is

not copulative!), "to serve as" or "to tend towards", "to

become" or "turn into" (with the preposition be with" (ie. , associated with, or on

the side of), "to happen", "to prosper" or

"succeed", and "to have happened". Tregelles' edition of Gesenius, published

in 1889, gives the follow- ing meanings: "to

be" or "to exist", "to become", "to be

done", "to be made" (all without

any associated preposition by modifying prepositions,

the verb is given an extended list of meanings which are

summarized in Appendix X. Since the

main point at issue in this

instance is the meaning of the verb where it is accompanied by no preposition

of any kind, the other passages will not be

examined at this point. In the

passive voice, Tregelles gives the

meanings as "to become", "to be made", and "to be done". In 1890 a Student's

Lexicon was published by Benjamin Davies, also based on Gesenius

(and Furst). He gives the basic

meanings as follows: "to

be" - whether with the meaning of "to exist" or "to live", or "to be

somewhere" - or as the logical copula between subject and predicate. As an

illustration of this last, he refers to Gen. 1.2. He then gives a second

group of meanings as follows: "to come into being", "to come

to pass", "to occur" or "happen"; and in the passive "to be done",

"to be made to be". In each of these Lexicons

I have examined every reference in the original Hebrew. In many instances the

appropriateness of the headings under which they

are listed can be very much a matter of opinion as is revealed by the

fact that the same reference will be reproduced under different

headings be different lexicographers. A list of these references

will be found in Appendix XI. I believe it would not be

incorrect to say that as these Lexicons appeared successively through

the years, the verb course of time viewed

somewhat differently. With Gesenius and Leo the principle or basic

view seems to have been that the verb meant essentially "to

be" in the ordinary English sense, with the concept of "existing" or

"living" next, and "becoming" only as a last alternative. By the time we come to

Brown, Driver, and Briggs, the modern standard of reference, the

position has altered. The basic mean- ings are now set forth under

four headings in this order; "to fall out", "to come

to pass", "to become", and finally, "to be". And even with respect to this last alternative, at the

appropriate place the authors add in parenthesis: "often with

the subordinate idea of becoming".

Thus the emphasis has shifted: where the copulative sense was originally listed as the primary one, it

is now listed as of least importance. Brown, Driver, and Briggs' Lexicon of the Hebrew language is by far the most exhaustive

available in English and here we find that far from being a rare or

exceptional meaning of of "coming to be" or "becoming"

is one of the most important and most fundamental meanings. I have examined every reference given in all these Lexicons as well as those provided in some of the more

elementary student's dictionaries of Hebrew and I have no hesitation in

saying that the evidence tells unmistakably against the present

commonly accepted view among "conservative" biblical

scholars who have expressed an opinion on the meaning of Gen. 1.2. Some of these writers will argue that when, it is followed by the preposition lamedh

( untrue as is easily shown by a study of cases where "became" is manifestly the correct rendering of in the Hebrew. A list of examples where why – will be found in Appendix XII. I would not say that the verb is never used

copulatively (though Ratschow and Boman hold this to be virtually so),

but I think it can be shown conclusively that the simple copulative use

is the exception and not the rule, and that such exceptions are very

rare indeed. In a few cases there appear to be exceptions only because

we have failed to observe the real meaning that the Hebrew writer

had in mind and our renderings are misleading. As we have seen, the

verb can be used to signify an "active existence" in

a situation where we would not expect to find "activity". Such a

case as Adam's nakedness is an example, for this is how he "went

about". In this instance, the English simply says that Adam was naked. But in the Hebrew processes of thinking, this is not a static

condition but a living circum- stance. The Hebrew mind animated situations far

more frequently than we do and it is this animation which gives the

Psalms, for example, such tremendous dramatic force. Like many non-Indo- European people, they thought of things as

having character, not merely characteristics. Even in Brown, Driver, and Briggs the list of supposedly cop- ulative uses includes numerous instances where the

case is very doubtful. For example, they list Deut.23.15,

"The servant which is escaped unto

thee....". But surely this is

an instance where modern English would

require the verb has rather than is. It is not a copulative use of the

verb: the verb verb of dramatic

action. One could never properly

substitute the word "has" in

such a sentence as "The field is flat", and the very fact that one can make the substitution

in the former but not in the latter case is sufficient to

demonstrate that the difference is a real one. In such a sentence as Gen.

17.1 (also included in the list in Brown, Driver, and Briggs) where

the text reads, "And when Abraham was ninety years

old....", we are not really saying that Abraham WAS ninety years. Obviously

Abraham is not the same "thing" as ninety years. We are actually

saying, "When he reached the age of....", ie., "When he became ninety years

old....". Brown, Driver, and Briggs

list altogether 45 references to show that 8 should be excluded,

being clearly not examples of a purely copulat- ive use. Furthermore, I believe another 7 at least

are equivocal since in every case the

translation "became" or "had become" would be equally, if not more,

appropriate. These are: Gen. 1.2; 17.1; Jud.11.1; II Ki.18.2; I Chron.11.20;

II Chron.21.20 and 27.8. This leaves us with only

30 examples out of a total (included under all headings listed in their

lexicon) of 1320 occurrences of have been proposed as

illustrations of the possible meanings of the verb. Moreover, of these 30,

at least 8 others are ill-chosen be- cause their use is either

anomalous (Gen. 8.5) or signifies "came to be" as in

Gen.5.4,5,8,11; 11.32; 23.1; and Exod.38.24. As we have already said,

it seems possible that some cases of a genuine copulative use of the

verb most writers for the

passage in Gen. 1.2 will be discovered if the Old Testament is searched

with sufficient care. But the fact

that Ratschow was not willing, after

making such an exhaustive study, to admit of a single

instance, suggests that such cases will certainly be the exception rather than

the rule. By contrast, the number of cases where the copulative

sense is indicated by the very omission of the verb in the Hebrew

is very great indeed. I have not made an actual count for the whole

Old Testament but I am sure that it would run into the thousands.

There are 600 cases in Genesis alone, for example. A single page in any English printing of the

Bible will usually show anywhere from

10 to 20 cases and most Bibles run into a thousand pages or

thereabouts for the Old Testament.

Simple arithmetic suggests,

therefore, that such omissions may run as high as five or ten thousand; five or ten thousand instances, that is to say, in which the

Hebrew has omitted the verb entirely because the meaning is simply

copulative. On the other hand, the

number of cases where the verb

can appropriately be rendered by some expression which denotes becoming

is very, very large indeed. Whatever else may or may

not be said, one certainly would not draw from this the

conclusion that the simple copulative use is the normal use. While it is highly likely that Brown,

Driver, and Briggs could have supplied

more examples had they considered it worthwhile, it still

remains true that the simple copulative sense is placed last in the list

and is then illustrated by a very small sample only, a substantial

proportion of even these being a little ambiguous. By contrast with the

actual evidence, one recent writer stated categorically that the

sense of "became" is so rare as to be found only six times in the

whole of the Pentateuch. As it stands, assuming the writer meant precisely

what his words imply, the statement is demonstrably false. For

example, the English reader will find the following seventeen

instances in Genesis alone, viz., Gen. 2.7, 10; 3.22; 9.15; 18.18; 19.26;

20.12; 21.20; 24.67; 32.10 (verse 11 in the Hebrew text);

34.16; 37.20; 47.20 and 26; 48.19 (twice); and 49.15. Other occurrences elsewhere are listed in

Appendix XIII: the total exceeds

133. Furthermore, it must be

remembered that these are not by any means all the instances in

which "become",

"had become", etc.) but only those observable in the Authorized Version. There are many other English translations which supply us with further

instances.* And it must be remembered

that English translations

represent only one group of versions among many. There are Latin, French, German, Greek,

and dozens of other versions besides the

English ones. In these one may observe many more instances. For example, the Latin

Vulgate has rendered thirteen instances in

Genesis chapter 1 alone! Even more strikingly, the Greek Septuagint

translation renders in Genesis 1. Throughout

the whole of Genesis this version trans- lated the verb as

"became" 146 times: in Genesis and Exodus together the total becomes 201

times: in the Pentateuch as a whole 298 times: and some 1500 times throughout

the whole Old Testament including * See on this, Chapter IV, The Witness

of Various Versions. the Apocrypha. These totals are, of course,

according to my own counting. The count may be

slightly out one way or the other, but certainly it is

essentially correct and probably errs only by being an understatement if

anything. I may have missed a few but I certainly did not invent any! Moreover, the figures do not include

cases where expresses by circumlocution its dynamic

sense of "becoming". The sad truth is that the issue can no

longer be explored except within the framework of a

controversy which has crystallized itself around the "Gap

Theory". When the challenge of

Geology brought into sharper focus the

importance of this particular exegesis, the argument was not

unnaturally shifted from the linguistic evidence of the text of Genesis itself

to an examination of other passages of the Bible which it was

believed contributed light on the matter. So the is sue be came one of the

"interpretation" rather than the precise and careful analysis of Gen.

1.2 which is really the critical issue. It may be argued with some

force that if the case is rested primar- ily on the linguistic

evidence of Gen .1.2, it can never have compelling weight because by far the

great majority of authorities are so strongly against it. But authorities are not always right.

For exam pie, from the very earliest

times in English translations that I have been able to examine thus far,

the fifth verse of the first chapter of the "Song of

Solomon" has been rendered, "I am black but comely....". I have so far found only one

honourable exception. Yet the truth of the matter is that the

Hebrew word translated "but" is more frequently rendered "and"

in the English of the Old Testament.

There is no question that

"but" is perfectly allowable here. Nevertheless, "and" is its more usual meaning,

and though there are a number of other alternatives that could

have been chosen, such as "yet", "neverthe- less", etc. , common

usage easily confirms the fact that the Hebrew waw is much more frequently

employed as a con-junctive than a dis- junctive. Normally the context readily determines

which it is. Then why has it been

rendered "but" in this passage where, by this simple expedient, the

speaker is in effect being made to apologize for the colour of her

skin? The answer, of course, is that

the choice was made on

prejudicial, not linguistic, grounds, though each * An approximate count shows that the

particle is trans- lated in the Old Testament

as 'and' some 25,000 times, and as 'but' some 3000 times. translator was probably quite unaware of

the way in which his bias was expressing

itself. The use of "but"

has nothing to do with scholarship at all. It has simply been accepted without

challenge because the implications

of it were not observed. I am persuaded that we

have wrongly reached the same kind of general agreement as to

the rendering of Gen.1.2, not on scholarly grounds but either because

the alternative simply did not occur to the translator or because he

desired to dissociate himself from a certain view of the earth's early

history which currently, at least, is said to find no support from

Geology. The emotional factor is often quite evident from the vehemence

with which the alternative rendering is disallowed. Climate of opinion

is simply against it but not , I believe, the linguistic evidence

itself. Some of this evidence is reviewed for several books of the Bible

in Appendix IV. CONCLUSION: In Appendix IV will be found

a rather involved examination of the evidence as found in five

representative books of the Old Testament; Genesis, Joshua, Job, two

Psalms, and Zechariah. This study has been put in an appendix in

order to remove it from the cursive text and to allow the reader to

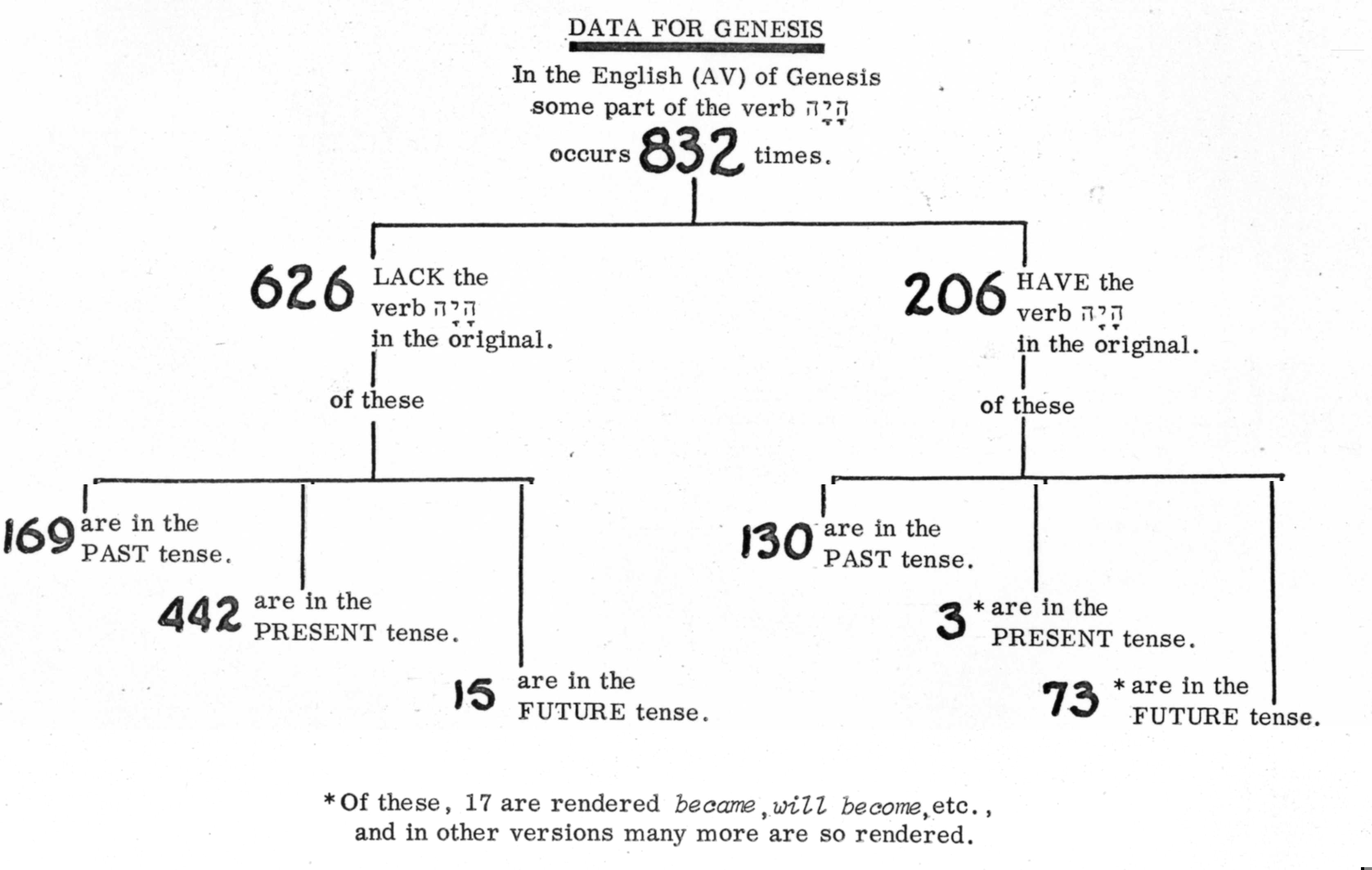

read on through without getting tiresomely bogged down in detail. The evidence shows that some part of the

English verb "to be" occurs in the Authorized

Version 832 times in the book of Genesis alone.* Any other English version would, of

course, have served the purpose of analysis

just as well. However, in the usual printing of the Authorized Version

text, italics are used for "supplied" words which simplifies the

counting, and of these 832 occurrences, 626 are not represented by any

form of the verb summary, where the copulative use of the

English verb "to be" occurs in the Authorized Version,

the Hebrew original does not employ the verb 626 occurrences of the

supplied English verb indicates that a sub- stantial number of them

(169 in all) are in the past tense. In this Appendix, a similar

breakdown was undertaken of the use of the verb "to

be" for the other books of the Bible listed above and a breakdown of the results

is tabulated on page 146. From this sample study I think

certain things emerge with respect to the use * See accompanying tabulation, page

58. First of all, it is

apparent that the verb ployed to express the

simple copula, whether the tense is past or present. It is more

frequently employed, however, when the tense is future. The second thing emerging

from this study is that the Hebrew writers did not find it necessary

to employ the verb make clear to the reader

whether the tense was past or present. In other words, the

introduction of the verb (as in Gen .1.2, for instance) is not simply a literary

device to inform the reader that this is how the situation was in the

past rather than how it is in the present. In the Book of Genesis, the

tabulation shows that in 169 cases the context is allowed to decide for

the reader that the events are past and the reader is left to surmise

for himself that in 442 cases the tense is present. The context

itself, in the absence of any expression of the verb The third thing is that the

verb of a specific kind is

involved. This does not mean change

in the sense that a past

situation is no longer true in the present, but rather that a pre sent situation

is changing, has changed from what it was, or will change in the future.

The argument that a past situation which has not continued into the

present automatically requires the employ- ment of the verb is very nicely represented

in English in a substantial number of cases by some form of the verb

"to become" or "to come to be". In a surprisingly large number

of cases where the use of such a form as

"become" or "became" as a substitute rendering will be found to

clarify the meaning of the text or, at the least, to make very good

sense. In the light of these

findings, it can hardly be maintained that to translate Gen. 1.2 as,

"but the earth had become a ruin, etc.", contravenes Hebrew usage.

If the meaning intended had been simply "the earth was a

chaos", even if we understand the word chaos in the Greek sense of

"waiting to be given form", the verb normally have been

employed in the original. Copyright © 1988 Evelyn White. All rights reserved

|